ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

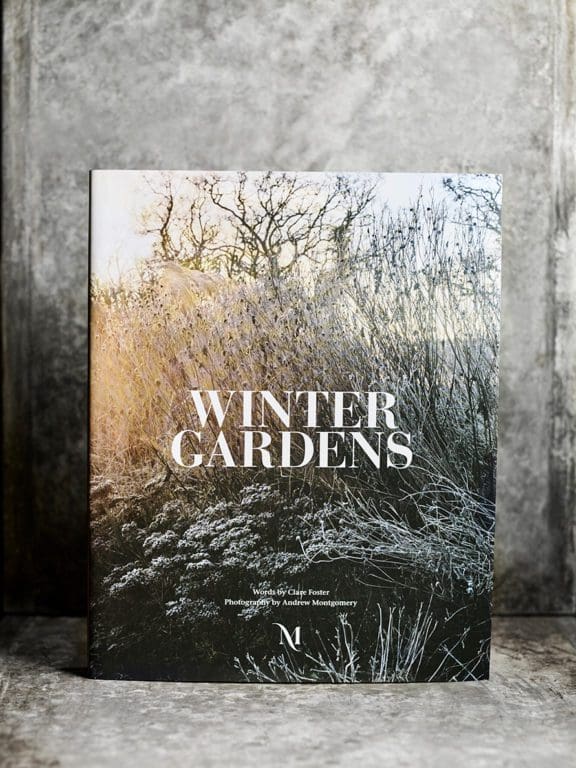

Last December, just days after Christmas, we received an email from Clare Foster, gardens editor at House & Garden magazine. She wanted to know if we would be happy for the garden at Hillside to be photographed by Andrew Montgomery for a new self-published book they were working on together. The focus of the book was to be gardens in winter and they had set themselves the task of getting it written, photographed, designed and published within 10 months.

On a perfect misty morning in early January with the garden covered in hoar frost Andrew arrived just before sunrise. He immediately got to work with total focus and proceeded to work into the early afternoon when the mist finally dissipated and his frost-bitten fingers could take the cold no more. The book has now been published and features gardens by Arabella Lennox-Boyd, Arne Maynard, Jinny Blom, Piet Oudolf and Tom Stuart-Smith amongst many others. Here Clare and Andrew tell us about how the book came about and what they feel is particular and special about the garden in winter.

Tell me how the idea for the book came about? What inspired you to create a book about winter gardens?

Clare: Andrew and I had worked on a couple of winter garden features for House & Garden and one in particular we had been trying to capture for a couple of years, waiting for the right moment. In lockdown, Andrew started photographing seed heads and ruminating on the idea of doing a book. I seized on the idea and came up with a list of other gardens which I thought captured the beauty of winter in very different ways. We were lucky – the weather was reasonably cold last winter – and we managed to get most of them photographed in atmospheric frost, mist or snow.

Andrew: Winter Gardens came about in December 2020, during the second lock-down. Having seen all my photography commissions put on hold until well into 2021, I had this free time all of a sudden where I could do what I wanted, so decided to photograph and put together my own book. Having spent the previous 10 months, including the first lockdown, putting together a book for Petersham Nurseries which was a self-published project, I knew I could do it. Winter Gardens was the perfect subject. Covid secure, I could shoot whenever I wanted with no human contact. More importantly it appealed to my own personal desire to see gardens in a new way. Stripped of colour, a monochromatic palette where light and shadow became paramount. The gardens became a muse for my love of black and white photography. Mist, snow, frost all enhanced the medium, which I felt had never really been properly explored in garden photography.

Gardens are often referred to as out of season in the winter. Can you tell us why you felt differently?

Clare: When you slow yourself down and really start looking at the garden and landscape in winter you notice the most amazing nuances. It is the sort of beauty that might not jump out at you, but once you adjust your eye it becomes a marvellous thing. There is no such thing as ‘out of season’ – winter is very much a season to be celebrated in the garden, with a chance to slow down and appreciate everything in suspended animation. And the other thing is, if you don’t have the quietness and downtime of winter you don’t appreciate the cycle of growth as it appears again in spring. It’s sort of magical, really.

Andrew: Out of season seems to suggest they have nothing to offer. I had a conversation with one of the gardeners at Great Dixter discussing frost. She remarked that the first frost was always the most magical, as if it signified the curtain call of Autumn, those brown warm shapes and tones suddenly enveloped by a crystal blue cloak, a portent of what is to follow. This sparked the need to witness and photograph this inaugural wintry pistol crack. So over previous winters I have always felt the need to try and capture this moment.

The winter season offers something different to capture, something much more subtle. The garden is dormant, quiet, its bones and earth bereft of colour, where weather dominates the mood and feel of the space, enhancing what is left for us to see. It also gives us a chance to really reflect on what went before, but also gives us hope as to what is to come. Winter is the season of reflection.

How did you go about selecting the gardens you chose for the book? What was the story you were wanting to tell?

Clare: We wanted there to be some very contrasting gardens in the book to show that there are different ways to bring beauty and interest into the winter garden. The book is divided into three sections that take you conceptually through early, mid and late winter, to show that winter is not a static season at all, but has its own momentum towards spring. Three essays group the gardens into different types: Beauty in Decay features gardens with grasses and seedheads; Silhouette and Structure looks at gardens with a stronger topiary framework; and A Shy Flowering contains gardens with winter or earliest spring flowers. The last garden in the book shows everything cut neatly down and mulched ready for spring. One senses the hope of the new year.

Is there anything you learned about the process of gardening while researching, writing and producing the book that was either new to you or came as a surprise?

Clare: I learned to really, really look at the process of senescence in my own garden. In certain plants, the seed heads and stems collapse quickly; others are incredibly strong and last for months and months before you have to fell them in March. I noticed what rain or frost did to my honesty seed heads and this close observation brought so much pleasure. I also learned quite a lot about snowdrops from the head gardener at Lord Heseltine’s garden at Thenford. They have a collection of about 900 varieties and she knows almost everything there is to know about propagating them.

Can you tell us about some of the challenges you face photographing gardens in winter?

Andrew: The challenges – well the obvious one is the cold. It’s debilitating both to people and battery life! Fingers become useless after prolonged exposure to the cold, disconnected from the brain you begin to fumble the camera controls, struggling to operate something which usually you do without looking. The cold becomes tiring, tripods and ladders too cold to touch with bare hands. Gloves, thermals and merino wool layers help massively. Cameras also don’t like the cold, and you have to acclimatise them slowly to the conditions, otherwise condensation builds up on lenses and viewfinders.

There’s also always a chance in the winter that you’re not going to be able to get to the garden you’re supposed to be photographing due to ice or heavy snowfall. Either that or, having headed off at dawn into the frost and snow, you find that by the time you get there it’s disappeared! One of the gardens was a particular challenge and it took four attempts to get the pictures that appear in the book. The garden is just off the M4 not far from London, not an area known for snow. The fourth attempt was only successful as I was supposed to be going down to Dorset to do a shoot that morning, but couldn’t get there as the A303 was snowbound. So I took a gamble on the fact that it was probably snowing at this other garden, which was much closer. This was at 5 a.m. so I just decided to turn up and hope the owners didn’t mind! Of course, I was incredibly lucky and got some beautiful shots of the garden in the snow.

The book is beautifully thought through, laid out and paced. Who designed it for you?

Andrew: I designed and laid out the whole book and the individual gardens and chapters. Editing is a process which I love. Pacing the run of photographs for each garden, juxtaposing images, mixing colour and black and white. It’s just like planning and planting a garden – extremely creative. You are mindful of what comes before and next, not wanting to repeat yourself visually. Always trying to make each image earn its right to be on that page and in the book.

Once I had everything laid out and the gardens organised into chapters, I would then work with a great guy called Anthony Hodgson who was able to put everything into Indesign for me and put the book together for printing. He also handled all the typesetting and font choices in the book.

Andrew, at the book launch you said that the image you took at Hillside which you titled The View to the Tump, ‘is probably the most spiritual picture I have ever taken.’ I’d really like you to expand on that and tell me why.

Andrew: The View to the Tump is an image that had been one of my favourites throughout the book’s editing process. It was the best shot from my day’s shoot at Hillside, but it was when I saw it enlarged to over 3ft by 2ft on the table in the printers that its power really struck me. I became quite emotional seeing it for that first time at that scale. I had only ever viewed it on my computer screen at home where it was no bigger than A4 size. The scale of the print, which was to be hung with two other prints of Hillside for an exhibition to celebrate the book launch of Winter Gardens, had made it an immersive experience.

Once hung on the wall I began to see that the image was a glimpse of another world, familiar to ours yet somehow removed. The gate in the image took on the metaphor of the entry into that other world, as if this was a glimpse of heaven beyond.

Now for me to say these things about any image, let alone one of my own, is unheard of, but this one is different and stems from my emotional reaction to it. This is a rare, profound feeling that has happened only once or twice in all my thirty years of taking photographs, but it’s the spiritual connection that The View to the Tump has that makes it unlike anything I have taken before.

Can you tell me what it is you see in winter seedheads and skeletons, which your son, Clare, described as a ‘a load of depressing old sticks’?

Clare: Every seed head has a different structure, a unique design that is revealed slowly as the plant decays. Some of them are really sturdy and strong, others are delicate and ethereal, but they are all marvels of nature. I find that photographing them sometimes makes me focus more keenly on them, especially if I’m doing close up or macro shots that reveal the tiniest detail. I think this is something that you almost have to learn to do, and I will try and teach my 17 year old son to open his eyes to it. But I don’t think he’s ready yet….

You first contacted us about this book just after Christmas last year, since when you have written, photographed, edited, designed, proofed and published this completely on your own. Can you describe what it has it been like self-publishing a book from scratch in just under a year and what have been the particular challenges?

Clare: It has been a complete whirlwind. We are both incredibly hard workers. We get things done, but it has been a fantastic experience because we have had complete creative control. Obviously Andrew takes the photographs and it was his eye that brought the book together, but he was very open to my suggestions and ideas and together I think we have made something that represents both our creative souls. We have made something with integrity that I think we are both incredibly proud of.

Andrew: The timescale to produce a book of this scale would normally be 1-2 years, so to do it in 10 months would, to a normal publisher, be impossible. We had planned out our production schedule, image editing, design, writing, copy editing and proofing to meet our deadline of July 29th. Files would then be sent to the printers and our book scheduled to arrive mid-October for our November 4th publication deadline.

The challenge was doing this alongside our normal careers at the same time, which put a huge amount of pressure on both of us. We just knuckled down and worked all hours on it. We really wanted the book to be published this winter, not a year later, and it could not come out at any other time of year either.

The most stressful part was waiting for the ship carrying our books to arrive in Portsmouth. The pandemic had played havoc with shipping routes and schedules and watching the boat make its eight week voyage over a live-view feed on the internet with publication day looming was nerve-wracking. In the end I took delivery with just two days to spare!

Now that you have one book under your belts do you have any plans for another? If so, are you able to tell us anything about it?

Clare: Yes – another book is definitely in the pipeline. Another garden book. Watch this space!

Andrew: Well, it’s very exciting that we know what book two will be! It’s going to be another garden based book, but we can’t say more than that. We are aiming to release it sometime in 2023, but to enable us to do that book we are working as hard as we can now to make Winter Gardens the success we feel hopefully it deserves to be!

Winter Gardens costs £45 and is available to buy directly from Montgomery Press.

An exhibition of Andrew’s photographs from the book is being held in the old tithe barn at Thyme, Southrop, near Lechlade until April 4 2022.

Interview: Huw Morgan | All photographs © Andrew Montgomery

Published 4 December 2021

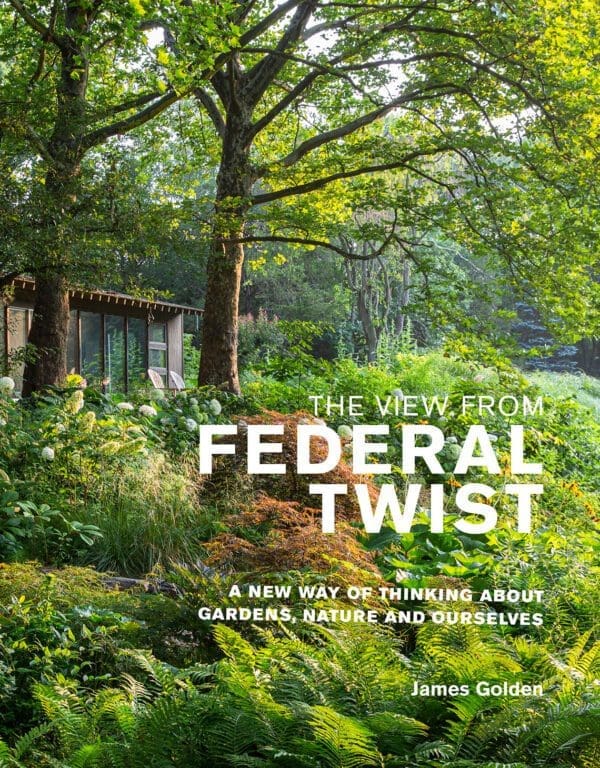

I first became aware of James Golden in 2009 when Huw showed me his short online review of my book Spirit: Garden Inspiration published on his blog The View from Federal Twist. From time to time Huw would direct me to James’ blog posts as he felt we had a shared perspective on gardens and I was always struck by the thoughtfulness and care in his writing, his philosophical and questioning approach to the matter of gardening and the undeniable beauty of the naturalistic plantings in his woodland garden. It was fascinating to see a garden being steered so apparently lightly and his low interventionist approach to working in his environment.

The following year James came to hear me speak about the Spirit book in New York and expressed an interest in my work on his blog, which is when Huw and I started an intermittent correspondence with him. It took a while before the stars aligned, but in 2015 James travelled to the UK and asked to visit the garden I had made at The Old Rectory in the Cotswolds. We made the arrangements, and I was very much looking forward to meeting him there, but then I was called away to Japan. James’ online account of his Old Rectory visit and his views of the Chelsea Flower Show garden I designed for Chatsworth and Laurent Perrier appeared shortly afterwards. It was clear he was a kindred spirit.

And then, last year, after we had finally published Tokachi Millennium Forest, Huw asked our publisher, Anna Mumford, what she was working on next. “Do you know James Golden?” she asked. “He’s writing a book about his garden at Federal Twist.” Huw told Anna about our tentative friendship and admiration of the spirit of his garden and suggested that I would be happy to support the publication of the book in any way I could. And so, last Sunday, James visited Hillside. It was a beautiful, mild autumnal day. The garden was at its pre-collapse peak and we walked the fields and gardens for several hours.

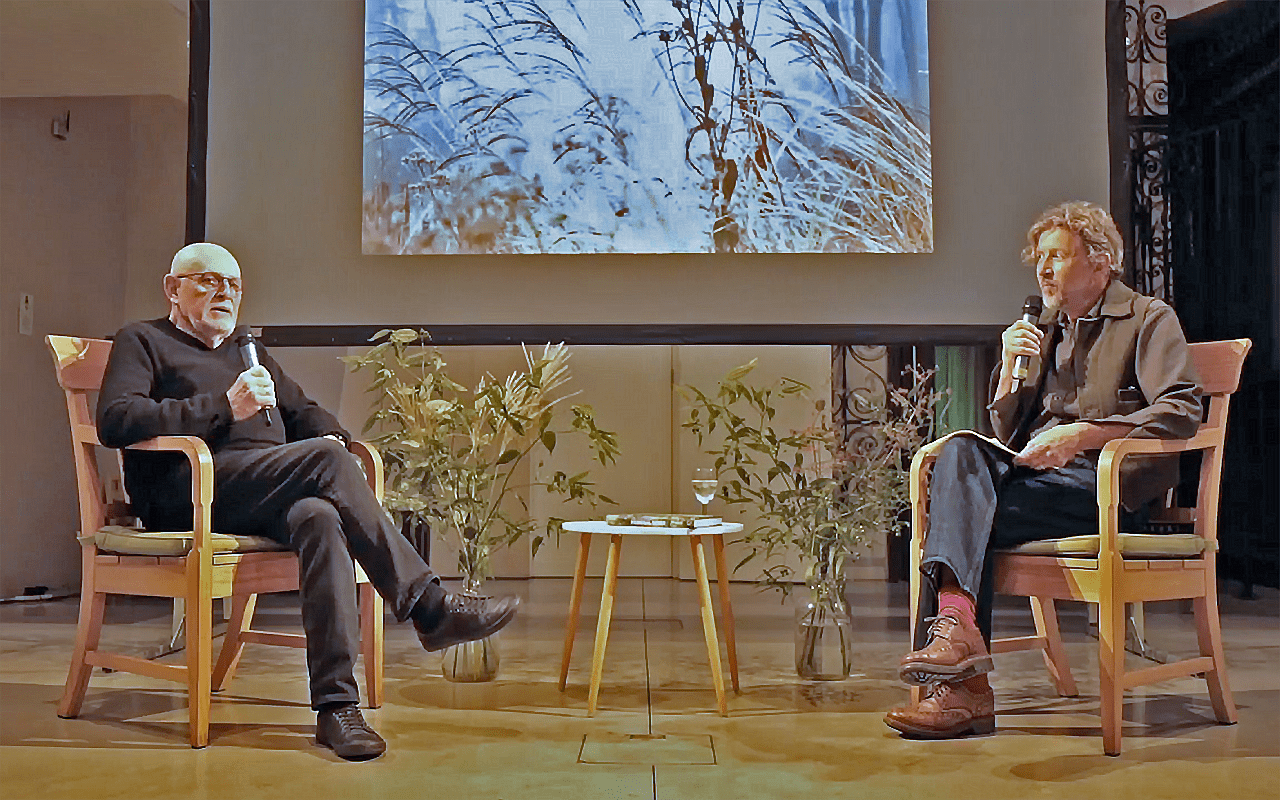

Then, on Tuesday evening, we sat together at The Garden Museum and had a conversation about the how, why and wherefore of his garden.

Below is a transcript of the beginning of that conversation, followed by an extract from James’ book, The View from Federal Twist: A New Way of Thinking about Gardens, Nature and Ourselves.

Dan: James, I wanted to open the conversation about this evocative place with you talking to us about your journey. How did you get to the point of being drawn to the clearing in the woods?

James: I usually say that I’m a latecomer to gardening, because I made my first substantial garden late in life. I grew up in the American south, in Mississippi, and almost unconsciously I fell in love with plants. I remember driving out of our small town over a wetland with my family and there’s this shrub blooming in the wetlands covered in white, flossy flowers and I asked my father what its name was and he didn’t know. That was the usual response I got when I asked about a plant. He knew how to grow potatoes and tomatoes, but he didn’t know this plant, which I learned probably fifteen years ago was called Baccharis halimifolia. At my grandmother’s house I saw an American beauty bush (Callicarpa americana), which has beautiful purple fruit, very notable in the landscape. Nobody knew what it was. I admired these things, but I never felt the urge to garden or to do anything with them.

I remember Cercis canadensis blooming in the spring. We call it redbud. You know, I think Cercis siliquastrum, which is a relative. It blooms in small purple, almost like buttons, just groups of little buds emerging from the dark bark. A beautiful, beautiful tree. But I think I felt, perhaps, that I was a boy so I shouldn’t appreciate things for their beauty. I’m not sure. Much later in life, actually after moving to New York, and my partner, now husband and I bought a house, a brownstone in Brooklyn and I started a small vest pocket garden. Only fifteen years ago we got a place in New Jersey and I started the gardening with a real passion and it became a really meaningful part of my life.

Dan: James, you say in the book that you entered the realm of garden making through reading.

James: I did. The first book on plants I read I think was The Well-Tempered Garden by Christopher Lloyd, which didn’t have a terrific meaning to me, being from America many of the plants weren’t known to me. Later I stumbled on a group of books that were coming out as Piet Oudolf was becoming more and more popular. Many of the books were by Noel Kingsbury and Piet Oudolf or by Henk Gerritsen and Piet Oudolf. They were large books with beautiful photographs and I fell in love with that kind of gardening. Subsequently I have read all of Dan’s books and learned gardening from books, not from actually gardening. I have done gardening and I do gardening, but I don’t particularly care for the labour of gardening.

Dan: I think through reading the book one of things that’s rather wonderful about the journey of the book is your obvious ability to observe very closely. It feels like you’ve really found your way into that place through that close observation and thinking time. Could you tell us what Federal Twist was like when you first found it and what drew you to decide that was the right place to be?

James: Federal Twist is in an area of several thousand acres of preserved forest on a ridge above the Delaware River. It’s still quite a wild-feeling place. We were looking for a new house. I also wanted to make a garden, but we found this mid-century house built in 1965, with many floor to ceiling glass windows, views out in all directions, and we fell in love with the house. It was described as vaguely Frank Lloyd Wright-like. It’s not Frank Lloyd Wright at all, but there are similarities it even had a few Japanese influences. I know the architect went through several designs in designing the house and at one point he had an entrance with a shoji screen, so he was thinking Asian and Japanese when he designed it.

We fell in love with the house and outside was an absolute ugly, derelict woodland. There was no open space. The soil was very moist. It was heavy clay. Behind the house was a monoculture of junipers, but we fell in love with the house. I had my doubts, but I had this stubborn feeling that I was going to make a garden here. I would find in books how to do it.

Dan: I was really taken by your relationship with the garden and felt that there were these wonderful parallels between how I feel about my place too. One of the things that I found really moving – there are two pieces that I’m pulling together, they appear at slightly different places early in the book – you say, ‘Federal Twist exists only because I create it from day to day. When I die it will cease to exist. We are one.’ And then you say, ‘I wanted to live in a garden, live a garden, in fact, to be a garden.’ And I think those are amazingly resonant things to read in a book. I wonder if you can talk to us a little more about that synergy.

James: Well, one aspect of gardening in the woods is that the woods is constantly trying to re-take the garden. This is so in America, especially, where there are so many woods. So there’s that constant give and take of the wood trying to move in. Trees pop up in the middle of the garden and you have to decide what to do about them. I was also very conscious that I was starting a garden quite late in life, so I was conscious of what my future might be. How many years I might have to work on this garden and what would happen to it when my life comes to an end. Not in an overly melancholic way. Having this garden is a very joyful thing, but I do think of where it belongs, ultimately, in the universe and I think it has to end when I end. Though I don’t do all the physical gardening, I am the person who knows how to take care of it and I don’t think anyone else could do that. Certainly, they could do that, but it would be a different garden.

Dan: I remember someone saying to me once, ‘The garden is the gardener.’ And I think there is so much truth in that.

James: I love that.

Dan: I wanted you to talk to me about the idea of prospect and refuge and the house in the clearing and the woods beyond. How does that play into how this place feels?

James: Well, when we bought the house there was no space, there was no clearing in the woods, so we removed seventy or eighty trees and created a clearing in the woods. It’s an archetypical American landscape type, because it goes back to the beginnings of our history and a land where white people moved in and probably really didn’t belong. They had to build houses with open spaces around them so they could see danger at a distance. The clearing in the woods, that concept, carries with it all of those, some of those emotions from the past, the idea of danger, of threat. Being in our house in the middle of the night or being in the garden in the night can be frightening.

Dan: I remember being a child growing up in a wood and I used to run along the lane at this time of year from the school bus and the exhilaration I felt as well, so it wasn’t entirely bad.

James: No, and then in the daytime it is entirely different, because most of the light comes from this oculus above created by the tops of the trees around the clearing, but in the morning and in the late afternoon the sunlight will break through the trees even when they are heavy with leaves and spotlight individual parts of the garden, which creates very bright spots and next to them very dark spots, so you can see this kind of beautiful chiaroscuro developing. It’s very transient, changes in light like that. That is one of the beautiful aspects of the clearing in this place.

Dan: You punched that hole in to see the sky, didn’t you? So you removed those trees to make that light pour in.

James: Yes, and the light’s important, because in this constricted space you’re conscious of the movement of the sun, and with the tall trees the shadows, hour by hour, change direction and change angle. Also, the sky opens up a vision of all kinds of weather. Beautiful cloud formations, snow. I have some wonderful photographs of cloud formations in the sky. It becomes sort of an observatory.

Dan: Beautiful. You say here – I’m just going to quote you again, as your writing’s so good – ‘I designed the garden to encourage exploration and attention to detail – to put you in a relationship with the garden. The experience is like giving over control, being open to feeling the garden push back a bit, and allowing the garden to take charge.’ If you could just tell us a little bit about that.

James: I actually came to experience this when I started opening the garden to other people. Though the garden is only one and a half acres in size, on a day when the American Garden Conservancy people come there might be over a hundred people visiting and quite a few of them would come to me and tell me they were lost and I thought, ‘How silly. It’s only an acre and a half.’ But in fact I garden on wet clay, I grow highly competitive plants which get very large – by midsummer much of the vegetation is above head height – so when you’re walking on a path you don’t see other paths and it is quite easy to get lost and become disoriented. I don’t, because I’m used to the space.

There are parts of the garden – I call it a prairie garden – prairies are naturally planted very thickly, so there are parts of the garden you can’t enter. The only way to move through the garden is along pathways that circulate through the planted areas and as you get lost or start wandering you do begin to feel that maybe there are places where you don’t belong, that maybe the garden is pushing back a little bit. The thought is that the garden is reminding you that many things are going on in it. Insects are reproducing, insects are pollinating, gathering pollen, bees are gathering pollen, the frogs are doing whatever they do. There are all sorts of life forms and processes going on in the garden and when you enter the garden you are not the centre of the garden suddenly. You are simply one of many different processes going on in the garden. I think having that perspective is a very important one in the world today.

A film of the talk will be available to watch on The Garden Museum website from next week.

Federal Twist is a landscape garden, not a traditional garden. It has no lawns, no flower beds, as such, only a naturally shaped landscape, a surface layered by perennials, grasses, shrubs, and a few understory trees. You move about on a series of paths that, all told, are far longer than you might expect in a relatively small garden. You are immersed in vegetation. Along the way are stone walls, reflecting pools, several small areas for lingering, and a small pond teeming with dragonflies, frogs, and other aquatic life. The purpose of the garden is reflection and pleasure—the simple pleasure of sitting out on the terrace overlooking the garden, feeling the inconstant breeze, listening to sycamore (Platanus occidentalis) leaves rustling above, to birdsong in the forest and to frogs croaking and splashing in the water below; exploring the pathways, many hidden by the abundant growth of midsummer, catching the light and shadow as they cross the land, glimpsing moments of intimacy—and for experiencing the marvels of memory, nostalgia, and feeling. The garden has no utilitarian purpose whatsoever, unless you allow for a human utility, a place to experience the atmosphere and the mood of the day, to think, to talk, to muse, to remember, to be.

Why do I call Federal Twist a landscape garden, not just a naturalistic garden? It violates many expectations of a landscape garden, certainly those of the 18th-century English landscape garden with its broad sweep of Picturesque landforms, water, forest, sky, classical follies and ruins so prominent in the paintings of artists, such as Claude Lorraine, who were the impetus for that style. I twist the concept a bit—quite a bit. One main reason is evident if you look at the image (below) of the sun rising behind the wall of trees on the far side of the garden, opposite the house, or the second image showing the long view of the garden with immense trees in the distance. These images make it dramatically clear that important elements of the garden are ‘capabilities’ of the landscape, not part of the garden at all. I didn’t make them; I simply recognized them and their value.

Back at the beginning, when I started the garden, I already recognized the landscape had a characterful identity and atmosphere. Any garden I might make would have to work with that landscape. Making the landscape part of the garden and the garden part of the landscape was my aim from the start. I wanted to anchor the garden in the landscape so there would be no visible boundary between one and the other. I wanted the garden and landscape to feel they were one. To do this required exaggerating views, manipulating scale, using simple, appropriate materials such as the local stone, amplifying it a bit by making it into walls and simple structures, adding an abundance of paths, using plants with a wildish quality, keeping dead tree snags—all toward the end of making the landscape garden appear effortless and at ease with itself.

Balancing the idea of the visual ‘landscape garden’ was my decision to make Federal Twist park-like. It is a garden of paths, and has as its primary purpose walking and exploring the landscape. Though you can stop and see the details, the focus is on the idea of landscape—the clearing in the woods, an American landscape, but one that faintly recalls its precedents in another time, across an ocean. If it were possible, I’d have the garden open for anyone to visit at any time, just as you might a public park.

Although Federal Twist is in a historical lineage that descends from other garden traditions, it makes no pretense to be what it isn’t. It is a distinctively American landscape type—a clearing in the woods—rather common here because of our extensive woodlands and history of living in them. America does not have the centuries of cultural history found in Europe and many other parts of the world—nothing like the layers of history you find in the UK, for example, where structures and artefacts perhaps several thousand years old may be uncovered in a field of cabbages. In contrast, Federal Twist feels rather recent, even transient—as if it might just disappear, be absorbed back into the woods.

It is an American landscape garden, but I do not mean it is representative of American gardens; it has no lawn, it is ‘untidy’, it is rough, and its boundaries are not obvious at all because they blend with the surrounding woods. It is the antithesis of most gardens and yards of suburbia where utility reigns, where foundation plantings closely hug houses and the use of trees and perennial plantings is stinted so they will not be impediments to mowing, where there is little room left for imagination, inspiration, contemplation.

Its design also is influenced by the idea of wilderness, of the forest and forest life, of the vast Midwestern prairies and meadow-like settings in the East, and by the strivings of some aspects of the American psyche, such as the vague desire to escape urban life for the country. Federal Twist resonates with the voices of such early American idealists as Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson, leaders of the Transcendentalist movement in the period of early intellectual awakening on this continent, in a time when forest was a far more pervasive landscape than today. In Nature, Emerson wrote:

In the woods, we return to reason and faith . . . Standing on the bare ground,—my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite space,—all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.

These words are classic in the American literary canon (and surprisingly reflect both German Romanticism and Asian religious precepts), but from the perspective of today, they sound distant and faint, even quaint.

Can a garden still be redemptive, transformative? Can it bring place and meaning together? It is very difficult even to raise those questions in the American culture of today.

Transcript of James Golden & Dan Pearson’s talk and photograph of them both courtesy The Garden Museum.

Extract from The View from Federal Twist: A New Way of Thinking about Gardens, Nature and Ourselves and James Golden’s photographs courtesy Filbert Press.

Published 6th November 2021

Eighteen months ago Guardian Faber approached me to compile a collection of articles from the ten years I wrote for The Observer. Natural Selection, with illustrations by Clare Melinsky, is due to be published this coming May and we prelude it here with a small selection to whet the appetite.

It was a privilege to be given the opportunity to write a weekly column and to record my gardening activities and ruminations in words over so many years. The pleasure I take in writing stems partly from this ability to record my gardening life and thoughts. The pieces span the whole decade and the shift – about half way through my time there – that charts the change from gardening in Peckham to the move we made to our land here in Somerset.

That move was the biggest change I have ever made in my gardening life and one that it has been good to look over again while editing the selection. The articles follow the course of a year, and explore the gradual seasonal changes that you are aware of through the act of gardening. Subject matters are invariably rooted in their moment, but they vary from the very practical and horticultural, to more in-depth essays about things I have fallen for or that have moved me and that I want to share with readers.

Writing is something that I enjoy for the act of pinning down a thought that may be fugitive or transitory. Gardening is when the best of these thoughts happen, and so one, it seems to me, would now be almost impossible to do without the other.

Fritillaria meleagris

SNAKES IN THE GRASS

5 April, London

One of my clients lives in a sturdy stone cottage in the Yorkshire Dales. It sits on the brow of a hill, facing south, with the valley sweeping away as far as you can see to either side. There are dry-stone walls sectioning the land and on the far hills the haze of heather smudges the tops in August. You feel the weather with intensity. When I was last there the January gales made the house shudder and the valley was a pure and glistening white with frost. But now, at the beginning of spring, the most extraordinary thing happens. The midwinter green increases in intensity over a week or so until it could only be described as luminous. It is like nature turning up the contrast so that the fields appear to be pulsing green. Go down into the valley and the hedges will be thrumming with activity. Bristling new shoots on the hawthorn, Stellaria smattering the base of the hedgerows and young nettles as soft as they ever will be, at the best moment for making into soup. Cowslips will be gathering in strength in the open ground where the turf is kept short and when the tops of the first new grass are bent over on a bright breezy day, the meadows will literally shimmer with reflected light. This is all good news after a long grey winter and I plan to make the most of this glorious moment. It involves studding the shiny new meadows with sheets of bulbs, not great sweeps of colour-heavy daffodils, but with species bulbs that will scatter colour.

No meadow in early April would really be complete without the Fritillaria meleagris and in a week these snakeshead fritillaries will be at their best. Pushing up on wire-thin stalks, they are almost impossible to see until they arch their heads over in readiness to flower. And flower they do in abundance when they decide they are going to naturalise a sward. The sight of them in countless numbers is breathtaking. They like to naturalise low-lying floodplains and there are some incredible colonies in the lowlands of Cambridgeshire, Oxfordshire and Wiltshire. They used to be more common, but with ground drained for agriculture and building spreading as it is, the wild colonies are now few and far between.

Last year I visited a good example just inside the ring road that runs around Oxford. It was odd to be among them, sitting in spring sunshine with the Juncus and ragged robin indicating how wet the land lay year round and the traffic hurtling by. Their chequered pattern never fails to delight me. It really is like the patterning on a snake. Mulberry overlaying pale silvery scales in the dusky forms and green overlaying white in the rare but ever-present albinos. The flower looks like it has been made from fabric and starched into position with its high-pleated ‘shoulders’.

I have no grass at home in London so I have chosen to keep a couple of dozen bulbs in a pot so that spring doesn’t go by without me enjoying them. I am amazed that they do as well as they do because they are a plant that looks so much better in the wild and only really does well where the ground is damp. I do nothing more with them than bring them out from the holding area in the shade when they show and then allow them to feed up their foliage until it withers in early summer sunshine after they have flowered. The pots are filled with Viola labradorica so that they are not too bare for the rest of the year and they are completely neglected beyond the watering that is needed to keep the Viola alive and kicking.

Establishing Fritillaria meleagris in a garden setting is fairly straightforward as long as you remember their requirement for damp ground. This is unusual in a bulb, for most like to be on the dry side when they are dormant. Soil that floods infrequently and in winter will be fine, but really they like to draw upon water rather than lie in it for long periods so it is worth bearing that in mind. Though I have had success planting the bulbs in the autumn at two-and-a-half times their own depth, as most bulbs like to be, I have heard that they prefer to be planted deep, up to 15 cm. If you can get plants pot grown, though not the cheapest way to introduce them in numbers, it is the surest way of getting them established. As with any other bulbs grown in grass, leave them for five to six weeks after the flowers fade to seed and store goodness for the following year.

The fritillarias are a huge tribe of wonderful treasures and most hail from Turkey and the Middle East where they bake bone dry not long after the spring rains are finished. It is hard to see many of these in the wild now because grazing has stripped the colonies as has unscrupulous bulb collection, but try and see them in the alpine houses of botanic and RHS gardens. You will be bewitched. Most of these species are beyond me at this point in my gardening history. They need to be grown in frames and given just-so attention, but there are several which are less choosy. The earth-brown and green F. acmopetala and F. pyrenaica are easy. My childhood neighbour Geraldine had a wonderful clump of the latter growing for years in free draining ground through some low perennial campanulas. Then there is the exquisite F. thunbergii from China, with its grass-like foliage, twisted at the tips to haul itself up into the low scrub in which it likes to grow. This is a woodlander that the garden designer Beth Chatto grows well against the odds in Essex. Its exquisite green bells are the perfect companions to Trillium and Uvularia in her sheltered woodland garden.

In areas of the country where the dreaded lily beetle has yet to make its presence felt or where you can be prepared to pick off the first generation of beetles and grubs, I will always make room for F. persica. Tall, at about 90 cm, in the strongest selection ‘Adiyaman’, the whirl of blue-green foliage is up early in March and the grape-purple flowers follow fast behind. This is a plant that loves to bake, so think about it being with thymes and small lavenders, Origanum and the like. It will be withered and below ground by mid-summer having lived fast and furious.

The Crown Imperials are closely related but a scale up again in impact. Perhaps they were brought here along with the tulips as part of the trading that used the ancient silk routes. Hailing from Turkey through to Kashmir they must have been exotic treasure, and their provenance explains why you often see them depicted in medieval woodcuts of apothecary gardens and in the floral paintings of the old Dutch masters. The flowers, which hang from a cluster at the top of a waist-high shoot, were said to have not hung their heads when Christ passed them on his way to the crucifixion. They are forever bound to bow their heads as a result. Lift them up and in the base there will be a tear of nectar at the heel of each petal.

The bulbs, which go in as usual in the autumn, have a pungent foxy odour and there is something of that in the glossy leaf. They are happy in a hot spot and in good hearty, free- draining soil. ‘Lutea’ is a bright chrome-yellow, ‘The Premier’ a dusky orange and there are brick reds that never look better than when basking in spring sunshine. They display none of the earthy tones of their many relatives, nor the snaky subtlety of our British native, but every bit as much individuality.

Rosa laevigata ‘Cooperi’

Rosa laevigata ‘Cooperi’

PLEASURE GARDEN

8 June, London

After finishing my studies at Kew in 1986, I spent about five years moving around: a year at Jerusalem Botanic Garden, a year a mile up a dirt track on Miriam Rothschild’s wild and woolly estate at Ashton Wold, and time out on the Norfolk Fens. I had plans with my partner at the time to buy a field on the Milford Haven estuary, where we intended to live on our houseboat and make a garden, but when my garden design business started to take off, I found myself inching back to London. I was twenty-seven and in love again, which is how I came to live on Bonnington Square, in south London.

The first time I saw the square I knew I wanted to live there. There was a party house with no floors, children running barefoot in the street, a cast of local characters who were the definition of bohemian, and the Bonnington Square Cafe, which is still run on a vegetarian co-operative basis. Friends dropped in with no notice and frequently stayed until dawn, and the boundaries between where you lived and where you spent your time were constantly blurred. One summer morning I awoke to find the outside of the house opposite had been papered from top to bottom in newspaper. Visitors often said it was like stepping back in time.

Although the Harleyford Road Community Garden on the other side of the square existed when I arrived, the greening of the square had now started. Cracks in the pavements had been dug out and planted up by the local guerrilla gardeners, and odd corners were already colonised. I had just been for the first time to New York, where I was inspired by the Operation Green Thumb community gardens on the Lower East Side. The same sense of a community working to improve its surroundings set the square apart from the roaring traffic of Vauxhall Cross, and that community has gone on to develop as one of my favourite gardens in central London.

My roof garden overlooked the site where this garden was created, on an area seven houses long that was bombed during the war. A chain-link fence surrounded the site, which had been turned into a children’s playground in the seventies, with a broken slide and dilapidated swing sitting on a pad of dog-soiled concrete. Although someone had planted a lone walnut tree, bindweed and buddleia had won the day.

In 1990 a builder asked the council for permission to store equipment on the waste ground, which alerted locals to the potential for development interest in this area of open land. Fast as lightning, Evan English, one of my neighbours, proposed that the site should be turned into a community garden. With a core group of residents behind him, he struck lucky with a local councillor who had one of the last GLC grants to give out to such a project. So, with just over £20,000 in our pockets and a team of council-appointed landscape architects, we put in the bones of the new garden.

The chain-link fence was replaced with railings, the tarmac and concrete with hoggin, and a series of raised beds created with topsoil spread over the basements of the old houses. A giant slip wheel, salvaged from the defunct local marble works, was partially reassembled to add a dramatic sculptural element. Another resident, the New Zealand garden designer James Fraser, and I put together the planting scheme and had a lot of fun mixing architectural New Zealand natives and English garden staples. A massive planting day that first autumn was followed by another party. None of this could have happened without Evan’s single-mindedness, and once the momentum was up, so was the support of the community. There was an annual street fair to raise additional funds for plants and furniture, and monthly workdays to keep the garden looking its best.

The square was given an entirely new focus with a garden at its core and created a renewed sense of pride among the residents. It was then given its official name, the Bonnington Square Pleasure Garden, partly a reference to the notorious seventeenth-century Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens, partly because it had been a pleasure to create and was intended to be a pleasure to use. Life on the square had changed. The picnic lawn was busy every weekend, and we saw people who had never ventured from their houses using the park as an extension of their homes.

The following year came the Paradise Project, a plan to green the streets around the square. We were given more help with funds for trees, and soon catalpas, Judas trees, mimosa and arbutus took to the pavements – and climbers to the walls of anyone who wanted to green their building. People quickly started to plant up the pavements in front of their houses. Window boxes of herbs and flowers appeared, old telegraph poles were colonised by morning glory and vines, and a rash of roof gardens appeared, so I was no longer alone in my green eyrie.

It is more than ten years since I left the square to make a garden of my own, but the Pleasure Garden has continued to evolve with the community, which is still very much behind it. A new generation of gardeners – many of whom had never gardened before moving there – keep it feeling vital. It is an object lesson in what can be achieved when people join forces to stop so-called ‘wasteland’ being lost to yet more bricks and mortar.

Rudbeckia laciniata

Rudbeckia laciniata

A WAY WITH THE PRAIRIES

8 December, Chicago

I have just returned from a lecture tour of the USA, where I caught the fall at its best and spent longer than ever before in Chicago, the City of Broad Shoulders. When I asked the origin of this nickname, it was proudly announced that the city believed that it should be able to carry the world through industry and innovation. After all, Chicago was home to the first skyscraper and to Frank Lloyd Wright, who developed his Prairie Style architecture in its suburbs. I had only known his wonderful, iconic Fallingwater, cantilevered over a cascade in woodland, so I was shocked to see these vast, low-slung Arts & Crafts family homes littering crisp expanses of lawn in the wealthy Oak Park area on the edge of town. Not a prairie in sight, but impressive nonetheless.

In the city centre, an industrious new wave of architecture has been revitalising the downtown area. On the way into Millennium Park, the beautiful Cloud Gate by Anish Kapoor reflects the spectacle of the city centre on its polished stainless- steel surface, capturing passers-by, skyscrapers, clouds and Frank Gehry’s Jay Pritzker Pavilion rearing up over the park like a silver dragon. Beyond the Gehry, and behind the dramatic Shoulder Hedge (to reflect the broad shoulders), lies the Lurie Garden, designed by Gustafson Guthrie Nichol, a celebrated new addition to the park. Piet Oudolf devised the planting for the garden and, among the glittering architecture, the essence of the long-lost prairie has been brought into the city.

Today, skyscrapers and concrete and lawns in the suburbs roll out from one to the next in a pristine carpet that has left no room for what gave Illinois its name as the Prairie State. The vast prairies once covered 570,000 square kilometres, from Canada to Texas, Indiana and Nebraska. In just over fifty years in Illinois alone, prairie that was seen as being rich for cultivation was swept aside to make way for industrial farming. The Lurie Garden, lovely as it is, with its tawny grasses and seeded perennials, could not have been a greater contrast to what lay around it.

Feeling inspired, and in need of some real landscape, I met up the next day with Roy Diblik, the man behind Northwind Perennial Farm, a pioneering nursery that specialises in native American plants. Roy had grown all the plants for the Lurie Garden and knew all there was to know about North American perennials. How brilliant that the garden has reactivated people’s interest in their own natives again, but how much more amazing to be taken to some of the restoration projects outside the city. Here, in relatively small pockets of land, a growing movement that started in the early sixties has seen prairies re-established by teams of volunteers. These nature lovers saw the need to act before all was lost, because today the original prairie only exists in slivers of land, rocky places that can’t be turned by the plough, and railroad embankments. Pointedly, and rather poetically, I thought, the pioneer cemeteries had also acted as an oasis for the plants that were swept away by the settlers, and it was the seed gathered in these sanctuaries that enabled the new reserves to be colonised.

I was shown one of the first restorations at the Morton Arboretum, an open area of about eight hectares. I felt so small with the grasses and eupatoriums standing at well over shoulder height, and it was ravishingly beautiful, with the only true green at that time of year being the ‘artificial’ green of the mown lawns of the gardens that lay beyond. Here there was every shade of brown, fawn and parchment white. In certain places, the hot cinnamon stems of Rudbeckia with coal-black seedheads and the grey-green of long-gone baptisia formed an undercurrent. Prairie dropseed, Sporobolus heterolepis, a grass that has a sweet, sugary perfume when flowering, formed low clearings where it had developed into a colony. Among the grasses, in a combination that it would be impossible to better in a garden, were jagged Eryngium, or rattlesnake master, and soot-black Echinacea. Silphium perfoliatum rose half as tall again as me. Its scalloped foliage had turned a leathery brown, and I stood for some time marvelling at the sculpture of it, thinking of my solitary plant in Peckham and how very far it was from its natural home.

Later in the day, Roy and I met up with Tom van der Poel, a charismatic leader in the contemporary prairie movement. He took us to Flint Creek, a six-year-old project of some twenty-five hectares. The land was purchased by Citizens for Conservation, a volunteer group which now owns 160 hectares. We plunged in after Tom as he took off along a tiny path, scattering handfuls of seed where he knew each species would have the best chance of thriving. As I followed, I asked how best to go about re-establishing an environment that had been erased well over a hundred years ago. ‘The restorations are a combination of science and art,’ he proclaimed. ‘The larger your perspective, the greater your understanding.’

He went on to explain the intricacies of the grassland as he showered seed into areas that were ‘ready’ for it; where the brome grass, the grass sown by the settlers for grazing, had been weakened enough by the other prairie plants. If they’re set free and given the room to thrive again, the process of reviving the natives is possible. Using the most vigorous species first and then inter-sowing weaker species such as the prairie dropseed and the bottle gentian, it has been possible to create microclimates to suit a wide range of plants. In just six years, 260 species have been re-established on this site alone.

Each site is sown according to the local conditions, which are often wildly removed from their original state – farmed and infertile, drained of the ground’s natural resources; but the volunteers are keen for diversity, so they ‘undo’ the sterile farmland by breaking the land drains to create a range of conditions again. The culture of burning sections to clear the thatch that builds up in time, as the Native Americans did, is still practised at the end of winter before growth starts. Tom said they only burn the prairie in sections, to allow the wildlife that has flocked back room to escape. ‘Building the food chain is just a small part of this work,’ he explained.

Every year another site is brought back in for re-colonisation by the efforts of volunteer groups such as these, and I hope that in our lifetimes this will be a chain reaction we can all be touched by.

Excerpts courtesy of Guardian Faber. Natural Selection will be published 4 May 2017, Guardian Faber, £20. Available now for preorder on Amazon.

Linocuts by Clare Melinsky

Dan is speaking about Natural Selection at the following events;

26th May Bath Festival

30th May Hay Festival