Last Monday we awoke to a pristine frost, the first of the year. It lay heavy, sweeping up to tickle the grassy banks, but sparing the giant dahlia in the shelter of the barn. For now. I was up early, the moon still in the sky, to check on the pelargoniums which I’d moved in under cover of the open barn the night before. It was the beginning of the season’s change. From now on the garden will drop back and recede into winter.

In the seven years we have been here this shift has happened almost exactly to the week, but with every year there has been increasingly more to draw from in the garden. Despite the freeze that saw tender nasturtiums wilted and the dahlias in the open blackened, we are far from done in terms of interest. The grasses have come into their own as the colour of flower fades elsewhere. Panicum virgatum ‘Rehbraun’ is of particular note, but it has taken this long to reach its current perfection. The last few weeks have seen this late season grass at its best, the smoky panicles forming a mist amongst the perennials. As the weather has cooled, the foliage has now coloured too, a deep mahogany red.

Foliage of Panicum virgatum ‘Rehbraun’

Foliage of Panicum virgatum ‘Rehbraun’

Picked in a bunch the flowers of the panicum act much as they do in the planting to veil their companions and create graphic sweeps with their flamed foliage. Almost anything works in this moody suspension of colour and here we have it with the very last of the Rudbeckia ‘Prairie Glow’. This short-lived perennial is easily raised from seed. Indeed, the plants that I have in the picking beds are variable for exactly this reason. A mix of embers and charcoal, black over red or orange, with some more fiery than others. Desite the strength of colour the impression is light for the flowers are small and held freely with room between each other. In my experience the freer draining the ground in the winter, the more likely you are to keep it. A pinch of seed, taken now and sown early under cover, will ensure that you have it next year.

Rudbeckia ‘Prairie Glow’

Rudbeckia ‘Prairie Glow’

The Coronilla valentina subsp. glauca ‘Citrina’ has a second season of flower once the weather starts cooling, its honeyed perfume noticeable quite some distance away. I have it planted by the path so that it is easy to inhale a big lungful. This modest, woody perennial is usually at its best in early spring, flowering prodigiously in March and April and then on into early summer after a warm winter. I put this second push down to youthful exuberance and do not expect the plants to keep this up for more than three years. In the third summer I will take cuttings and replace them in new positions for they are sure to exhaust themselves. Their presence is always light and delightful, the pale yellow pea flowers darker on the lip than the keel. If you can find them a sunny free-draining position, they are easy.

Coronilla valentina subsp. glauca ‘Citrina’

Coronilla valentina subsp. glauca ‘Citrina’

Persicaria virginiana var. filiformis is one of my favourite late season perennials. I grew them first in the Peckham garden, where they seeded freely into the shale I used for the paths. Their presence is light early in the year and, like the panicums, they take some time to come into their own in the latter half of the growing season. Grow them in a little shade or on the cool side of a building for the emerald green in the leaf to set off the maroon chevron of warpaint to best advantage. Out in the sun, the green pales and can look insipid and, as the greater part of the joy in this plant is the foliage, it is worth finding it just the right place. That said, the spires of tiny flowers are worth the wait, forming a pink haze that is hard to pin down at first, but bright and easily detectable once you find the miniature flowers scaling their wiry spires.

Foliage of Persicaria virginiana var. filiformis

Foliage of Persicaria virginiana var. filiformis

Flower spike of Persicaria virginiana var. filiformis

Flower spike of Persicaria virginiana var. filiformis

Berries of Malus transitoria

Berries of Malus transitoria

Our Malus transitoria coloured a bright, buttery yellow this year, before the leaves were stripped by gales to leave the berries hanging delicately in their thousands. The tiny amber beads, which darken to a reddish tan as they ripen, are perfectly bite-sized for the birds and every morning they are full of fluttering life. At this teetering point between the seasons this is a moment worth eking out and savouring. A last flash of life before winter gets its grip and competition for the berries will see them vanish with the last of the flowers.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photos: Huw Morgan

Published 11 November 2017

This week we have reached the tipping point where autumn turns to face winter. There is a nip in the morning air and, as soon as the sun sets, a jacket and scarf are needed outside. So far we have avoided a frost, but it is only a matter of time, and so the pumpkins that until last weekend were ripening in October sunshine, are now safely tucked up inside.

These moments when the seasons make a noticeable shift towards the next also have an effect both on what is available to eat in the garden and what we feel like eating. The first celeriac have been pulled, and have so far been used in a sharply dressed remoulade and a creamy soup flavoured with bay and nutmeg. Pumpkins have been made into vibrant curries with lemongrass, ginger and coriander, or hearty gratins with fontina cheese and a crust of herbed breadcrumbs. We are also just starting on the brassicas, plumping for romanesco and early sprouting broccoli before we get firmly stuck into the savoys and kales. There are also the windfalls to use up before they turn to mush, and the very last of the hedgerow fruits, both of which give us a connection back to the last days of summer, when there was still some heat in the sun.

Windfall apples and pears from our neighbours

Windfall apples and pears from our neighbours

Although we still have a few summer sown lettuces hanging on in there, they quickly go to seed now, and can’t be relied on to provide salad for much longer. However, the chicories and radicchios are invaluable at this time of year, as they are incredibly hardy and come into their own as the temperatures fall. We grow those varieties that we have found to be the most reliable over the years; the elongated blood red Rossa di Treviso (both Tardivo and Svelta), the spherical, strongly veined Palla Rossa and the delicately mottled Variegata di Castelfranco. These we sow throughout the summer, starting in May for summer salad leaves, with successional sowings in June, July and August. The June and July sowings are now hearty enough to eat, while the plants from the final sowing will keep us going through the Christmas period and into the new year.

As the season progresses the bitter taste of chicory provides a welcome and fresh contrast to the roots and squashes which increasingly will be either roasted, mashed or baked in vegetable casseroles. Paired with ingredients that provide a sweet or earthy foil to their bitterness, salads of chicory make regular appearances on our winter table.

The mottled leaves of Chicory ‘Variegata di Castelfranco’ develop as the weather gets colder

The mottled leaves of Chicory ‘Variegata di Castelfranco’ develop as the weather gets colder

This salad bridges the autumn and winter larders by using the first of the chicory hearts, combined with the familiar autumn combination of apple and blackberry, with bite provided by crisp, roast hazelnuts. Here I have used both the hearts and outer leaves of Variegata di Castelfranco, but you can use a mixture of any of the green and red varieties available. For the dressing I use hazelnut oil and a spoonful of homemade bramble jelly to accentuate the flavour of the main ingredients. Any lightly flavoured oil such as rapeseed or sunflower and a little honey will do just as well. It is important that the apple slices hold their shape when cooked, so choose a firm eating apple. Pears work equally well as and, as the blackberries disappear until next year, the addition of a sharp blue cheese such as Gorgonzola, Roquefort or Picos de Europa adds a piquancy that goes well with the nuts.

This is good served with celeriac or parsnip soup, or a creamy pumpkin pasta or risotto.

INGREDIENTS

Salad

1 large or 3 small heads of chicory or radicchio

2 apples

100g blackberries

100g hazelnuts

A large knob of butter, about a tablespoon

1 tablespoon hazelnut or other lightly flavoured oil

Dressing

1 tablespoon cider or sherry vinegar

2 tablespoons reduced blackberry juice

1 teaspoon bramble jelly or honey

6 tablespoons hazelnut or other lightly flavoured oil

A large pinch of sea salt

Serves 4

METHOD

Remove the leaves from the chicory and tear into large pieces, discarding any coarse parts of the central rib. Wash in cold water and then dry in a salad spinner or clean tea towel. Keep to one side.

Put the blackberries in a small pan with a tablespoon of water. Put on a low heat with the lid on and gently bring to a simmer for a few minutes until the fruit gives up its juice. Do not allow to boil.

Strain the blackberries in a sieve over a bowl and reserve. Put the juice back in the pan and simmer until reduced to about two tablespoons. Reserve for the dressing.

Put the hazelnuts on a baking tray into a hot oven (200°C) for 5-8 minutes. Check them regularly to ensure they don’t burn. Remove the nuts from the oven and tip into a clean tea towel. Gather the four corners of the cloth together and rub the nuts hard to remove the dry skins. Remove the cleaned hazelnuts from the cloth and reserve.

Peel and core the apples. Cut into quarters and then cut each quarter into four slices. Put into a bowl of water acidulated with lemon juice to prevent them discolouring. In a large, heavy-bottomed frying pan, which is large enough to take all of the apple slices, heat the hazelnut oil and butter together over a moderate heat. Remove the apple slices from the bowl of water and dry on a clean cloth. When the butter starts to foam, lay the slices of apple in the pan. Turn the heat up and cook until they start to caramelise. Carefully turn the slices over and cook until browned on the other side. Remove the apple slices from the pan with a slotted spoon, being careful not to break them. Put on a piece of kitchen paper.

Make the dressing by putting the vinegar, reserved blackberry juice, bramble jelly or honey and salt into a bowl. Whisk until the salt has dissolved. Add the oil and whisk again until emulsified.

To assemble the salad arrange the chicory leaves on a large serving plate. Distribute the apple slices, blackberries and hazelnuts evenly and then spoon over the dressing. Eat immediately.

Recipe & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 4 November 2017

Sandwiched between storms and West Country wet, a miraculous week fell upon the final round of planting. We’d been lucky, with the ground dry enough to work and yet moist enough to settle the final splits from the stock beds. It took two days to lay out the plants and then two more to plant them and the weather held. Still, warm and gentle.

I’ve been planning for this moment for some time. Years in fact, when I consider the plants that I earmarked and brought here from our Peckham garden. They came with the promise and history of a home beyond the holding ground of the stock beds, and now they are finally bedded in with new companions. There are partnerships that I have been long planning for too but, as is the way (and the joy) of setting out a garden for yourself, there are always spontaneous and unplanned for juxtapositions in the moment of placing the plants.

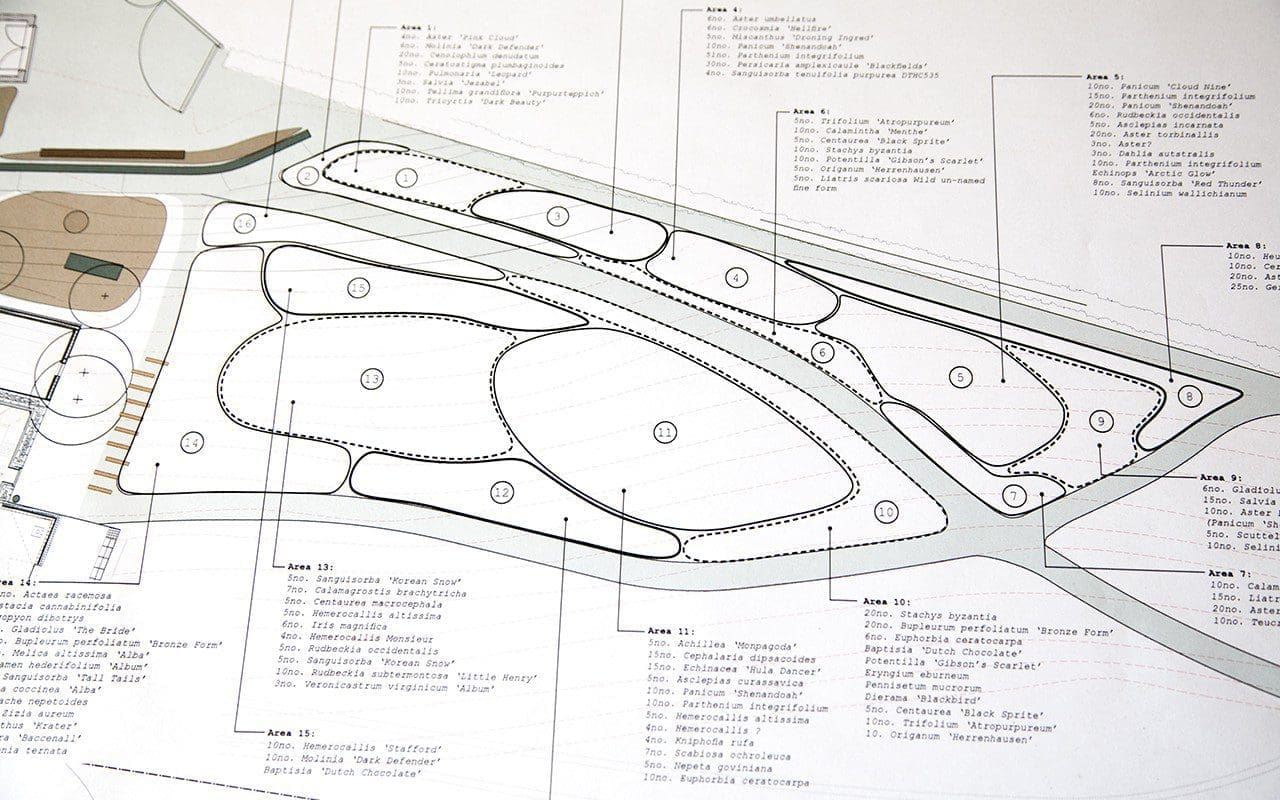

The autumn plant order was roughly half that of the spring delivery, but the layout has taken just as much thought in the planning. I did not have a formal plan in March, just lists of plants zoned into areas and an idea in my head as to the various combinations and moods. It was the same this autumn, but forward thinking was essential for the combinations to come together easily on the day. Numbers for the remaining beds were calculated with about a foot between plants. I then spent August refining my wishlist to edit it back and keep the mood of the garden cohesive. The lower wrap, with its gauzy fray into the landscape, allows me to concentrate an area of greater intensity in the centre of the garden. The top bed that completes the frame to this central area and runs along the grassy walk at the base of the hedge along the lane, was kept deliberately simple to allow the core of the garden its dynamism.

The zoning plan for the central section of the garden

The zoning plan for the central section of the garden

The central path with the top and central beds to either side

The central path with the top and central beds to either side

The top of the central bed

The top of the central bed

The end of the central bed

The end of the central bed

The middle of the top bed

The middle of the top bed

The end of the top bed

The end of the top bed

My autumn list was driven by a desire to bring brighter, more eye-catching colour closer to the buildings, thereby allowing the softer, moodier colour beyond to recede and diminish the feeling of a boundary. The ox-blood red Paeonia delavayi that were moved from the stock beds in the spring and now form a gateway to the garden, were central to the colour choices here. They set the base note for the heat of intense, vibrant reds and deep, hot pinks including Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’, Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’ and Salvia ‘Jezebel’ on the upper reaches. The yolky Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’, lime-green euphorbias and the primrose yellow of Hemerocallis altissima drove the palette in the centre of the garden.

Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’

Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’

Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’

Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’

Salvia ‘Jezebel’

Salvia ‘Jezebel’

Once you have your palette in list form, it is then possible to break it down again into groups of plants that will come together in association. Sometimes the groups have common elements like the Panicum virgatum ‘Shenandoah’, which link the new beds to the ones below them. Although I don’t want the garden to be dominated by grasses, they make a link to the backdrop of the meadows and the ditch. They are also important because they harness the wind which moves up and down the valley, catching this unseen element best. Each variety has its own particular movement; the Molinia caerulea ‘Transparent’, tall and isolated and waving above the rest, registers differently from the moody mass of the ‘Shenandoah’, which run beneath as an undercurrent.

To play up the scale in the top bed, so that you feel dwarfed in the autumn as you walk the grassy path, I have planned for a dramatic, staggered grouping of Panicum virgatum ‘Cloud Nine’. They will help to hold the eye mid-way so the planting is revealed in chapters before and then after. This lofty grass with its blue-grey cast will also separate the red and pink section from the violets and blues that pick up in the lower parts of the walk to link with the planting beyond that was planted in the spring. These dividers, or palette cleansers, are important, for they allow you to stop one mood and start another without it jarring. One combination of plants can pick up and contrast with the next without confusion and allow you to keep the varieties in your plant list up for interest and diversity, without feeling busy.

Each combination within the planting has its own mood or use. Spring-flowering tellima and pulmonaria will drop back to ground-cover after the mulberry comes into leaf and the garden rises up around it. Aster ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’ and Schizostylis coccinea ‘Major’ beneath the Paeonia delavayi for late season colour and interest. The associations that are designed to jump the path from one side to the other in order to bring the plantings together are key to cohesiveness. The sunny side of the path favours the plants in the mix that like exposure, the shady side, those that prefer the cool, and so I have had to be aware of selecting plants that can cope with these differing conditions. Consequently, I have included plants such as Eurybia divaricata that can cope with sun or shade, to bring unity across the beds. The taller groupings, which I want to feel airy in order to create a feeling of space and the opportunity of movement, always have a number of lower plants deep in their midst so that there is room and breathing space beneath. Sometimes these are plants from the edge plantings such as Calamintha sylvatica ‘Menthe’, or a simple drift of Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield’, which sweeps through the tall tabletop asters (Aster umbellatus). This undercurrent of the adaptable persicaria, happy in sun or shade, maintains a fluidity and movement in the planting.

Stock plants of Panicum virgatum ‘Cloud Nine’

Stock plants of Panicum virgatum ‘Cloud Nine’

Schizostylis coccinea ‘Major’

Schizostylis coccinea ‘Major’

Aster umbellatus and Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield’

Aster umbellatus and Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield’

Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’

Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’

The combinations, sixteen in total, were then focused by zoning them on a plan. The plan allowed me to group the plants by zone in the correct numbers along the paths for ease of placement. Marking out key accent plants like the Panicum ‘Cloud Nine’, Glycyrrhiza yunnanensis, Hemerocallis altissima and the kniphofia were the first step in the laying out process. Once the emergent plants were placed, I follow through with the mid-level plants that will pull the spaces together. The grasses, for instance, and in the central bed a mass of Euphorbia ceratocarpa. This is a brilliant semi-shrubby euphorbia that will provide an acid-green hum in the centre of the garden and an open cage of growth within which I can suspend colour. The luminous pillar-box red of Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’ and starry, white Dahlia merckii ‘Alba’. Short-lived Digitalis ferruginea were added last to create a level change with their rust-brown spires. However, I am under no illusion that they will stay where I have put them. Digitalis have a way of finding their own place, which isn’t always where you want them and, when they re-seed, I fully expect them to make their way to the edges, or even into the gravel of the paths.

Euphorbia ceratocarpa

Euphorbia ceratocarpa

Dahlia merckii ‘Alba’

Dahlia merckii ‘Alba’

Hemerocallis altissima

Hemerocallis altissima

Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’

Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’

Over the summer, I have been producing my own plants from seed and it has been good to feel uninhibited with a couple of hundred Bupleurum longifolium ‘Bronze Form’ at my disposal to plug any gaps that the more calculated plans didn’t account for. Though I am careful not to introduce plants that will self-seed and become a problem on our hearty soil, a few well-chosen colonisers are always welcome for they ensure that the garden evolves and develops its own balance. I’ve also raised Aquilegia longissima and the dark-flowered Aquilegia atrata in number to give the new planting a lived-in feeling in its first year. Aquilegia downy mildew is now a serious problem, but by growing from seed I hope to avoid an accidental introduction from nursery-grown stock. The columbines are drifted to either side of the path through the blood-red tree peonies and my own seed-raised Hesperis matronalis var. albiflora. For now they will provide me with an early fix. Something to kick-start the new planting and then to find their own place as the garden acquires its balance.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 28 October 2017

The self-sown sunflowers from the previous incarnation of the garden were the reminder that, just a year ago, we were growing the last of the vegetables here. I had allowed them the territory in the knowledge that this would be the end of their era, for they were in the bed that I now need back to complete the planting of the garden.

Felling them before they were finished was a relief, for suddenly, once they were gone, there was breathing space and the room to imagine the new planting. I’d also left the aster trial bed until the very last minute, eking out the weeks and then the days of its final fling. On the bright October day before we were due to lift, the bed was alive with honeybees, making the final selection of those that were to be kept for the garden that much more difficult. It was time to liberate the last of the stock beds, though, and to prepare the ground they occupied for a new planting.

The central bed cleared of sunflowers and ready for planting. The edge planting went in in April

The central bed cleared of sunflowers and ready for planting. The edge planting went in in April

Newly planted divisions of Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’ in the cleared central bed

Newly planted divisions of Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’ in the cleared central bed

Planning what to keep and what to part with is difficult until the moment you make the first move. Over the last three years we have been keeping a close eye on the asters that will make it into the new planting. Keeping the best is the only option, for we do not have the space elsewhere and the overall composition is dependent upon every choice being right for the mood and the feeling that we are trying to create here. So gone are the Symphyotrichum ‘Little Carlow’ which, although a brilliant performer, needing no staking and being reliable and clump-forming, are altogether too dominant in volume and colour. Aster novae-angliae ‘Violetta’ is gone too. Despite my loving the richness of its colour, having got to know it in the trial bed I find it rather stiff and heavy and I want the asters here to dance and mingle and not weight the planting down.

The Aster turbinellus, for instance, has been retained for the space and the air between the flowers, as has Symphyotrichum ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’ for its sprays of tiny, shell-pink flowers. I have also kept the late-flowering Aster trifoliatus subsp. ageratoides ‘Ezo Murasaki’ for its modest habit and almost iridescent violet stars held on dark, wiry stems. I have always known that Aster umbellatus would feature in the planting, and so I lifted and split my three year old trial plant last autumn and divided it into six to bulk up this summer. There were many more that didn’t make the grade though, and I was torn about losing them, my self-discipline wavering at times. However, Jacky and Ian who help us in the garden eased my conscience by taking a number of the rejects home with them, and the space left behind, now that they are gone and I have finally committed, is ultimately more inspiring.

Asters to be kept were marked with canes

Asters to be kept were marked with canes

Ian and Sam digging over the upper bed after removal of the asters. The Aster umbellatus divisions and Sanguisorba ‘Blackfield’ stock plants in the middle of the bed await replanting

Ian and Sam digging over the upper bed after removal of the asters. The Aster umbellatus divisions and Sanguisorba ‘Blackfield’ stock plants in the middle of the bed await replanting

The reject asters

The reject asters

This is the second phase of rationalising the stock beds. In the spring, and to enable the preparation of the central bed, I split and divided the plants that I knew I would need more of come autumn, and lined these out in the top bed to bulk up; the lofty Hemerocallis altissima, brought with me from Peckham and prized for its delicate, night-scented flowers, the refined Hemerocallis citrina x ochroleuca, and the true form of Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’, originally divisions from plants in the Barn Garden at Home Farm which I planted in 1992.

I have not found a red day-lily I like more for its rustiness and elegance, and some of the ‘Stafford’ I have been supplied with more recently have notably less refined flowers and a brasher tone. I have planned for it to go amongst molinias so that the flowers are suspended amongst the grasses. Hemerocallis are easily divided and in the spring the stock plants were big enough to split into ten or so; the numbers I needed for their long-awaited integration into the planting. In readiness for setting out, and with the asters gone, we have now reduced the foliage of the daylilies by half, lifted them and then left them heeled in for ease of lifting and replanting.

Hemerocallis, crocosmia and kniphofia stock plants cut back, heeled in and ready for replanting

Hemerocallis, crocosmia and kniphofia stock plants cut back, heeled in and ready for replanting

A division of Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’ laid out for planting

A division of Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’ laid out for planting

Jacky and Ray clearing and preparing the end of the upper bed

Jacky and Ray clearing and preparing the end of the upper bed

The kniphofia and iris I had decided to keep went through the same process in March, and so the Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’ and Iris magnifica were moved directly into their new positions where, just a week before, the sunflowers had towered. Similarly, the Gladiolus papilio ‘Ruby’ and Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’, which have both increased impressively, were lifted and moved into their new and final positions. This was in order to clear the old stock beds to make way for the autumn splits and keep the canvas as empty as possible so that I can see the space without unnecessary clutter when setting out.

The remaining trial rows – some Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield that I want in number and two white sanguisorba that will provide height and sparkle in the centre of the garden – were cut back to knee height, lifted and then split in text-book fashion with two border forks back to back to prise the clumps apart. Where the plants were not big enough I was careful not to be too greedy with my splits, dividing them into thirds or quarters at most.

Dan splitting a stock plant of sanguisorba with two border forks

Dan splitting a stock plant of sanguisorba with two border forks

A sanguisorba division ready for heeling in

A sanguisorba division ready for heeling in

The grasses to be reused from the trial bed will be divided and planted out next spring

The grasses to be reused from the trial bed will be divided and planted out next spring

Although October is the perfect month for planting, with warmth still in the ground to help in establishing new roots before winter, I have had to work around the trial bed of grasses and they now stand alone in the newly empty bed. Although I will be planting out pot-grown grasses next week, autumn is not a good time to lift and divide grasses as their roots tend to sit and not regenerate as they do with a spring split.

The plants I put in around the Milking Barn this time last year are already twice the size of the same plants I had to wait to put in where the ground wasn’t ready until the spring. I hope that the same will be true of this next round of planting, which will sweep the garden up to the east of the house and complete this long-awaited chapter.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 21 October 2017

I am currently readying myself for the push required to complete the final round of planting in the new garden. The outer wrap went in at the end of March to provide the frame that will feather the garden into the landscape and, with this planting still standing as backdrop, I have been making notes to ensure that the segue into the remaining beds is seamless.

The growing season has revealed the rhythms and the plants that have worked, and the areas where tweaking is required. Whilst there is still colour and volume in the beds I want to be sure that I am making the right moves. The Gaura lindheimerei were only ever intended as a stopgap, providing dependable flower and shelter for slower growing plants. They have done just that, but at points over the summer their growth was too strong and their mood too dominant, going against much of the rest of the planting. This resulted in my cutting several to the base in July to give plants that were in danger of being swamped a chance, and so now they will all be marked for removal. Living fast and dying young is also the nature of the Knautia macedonica and they have also served well in this first growing season. However, their numbers will now be halved if not reduced by two-thirds so that the Molly-the-Witch (Paeonia mlokosewitschii) are given the space they need for this coming year and the Panicum virgatum ‘Shenandoah’ the breathing room they require now that they have got themselves established.

Gaura lindheimerei

Gaura lindheimerei

Knautia macedonica with Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’

Knautia macedonica with Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’

I will also be removing all of the Lythrum salicaria ‘Swirl’ and replacing it with Lythrum virgatum ‘Dropmore Purple’. I was so very sure when I had them in the stock beds that both would work in the planting but, once it was used in number, ‘Swirl’ was too dense and heavy with colour. The spires of ‘Dropmore Purple’ have air between them and this is what is needed for the frame of the garden not to be arresting on the eye and so that you can make the connection with softer landscape beyond.

Lythrum virgatum ‘Dropmore Purple’ (front) with Veronicastrum virginicum ‘Album’ and Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’ (behind)

Lythrum virgatum ‘Dropmore Purple’ (front) with Veronicastrum virginicum ‘Album’ and Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’ (behind)

The larger volumes of Lythrum salicaria ‘Swirl’ can be seen at the front of this image

The larger volumes of Lythrum salicaria ‘Swirl’ can be seen at the front of this image

As a gauzy link into the surroundings and as a means of blurring the boundary the sanguisorba have been very successful. I trialled a dozen or so in the stock beds to test the ones that would work best here. I have used Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’ freely, moving them across the whole of the planting so their veil of tiny drumsticks acts like smoke or a base note. A small number of plants to provide cohesiveness in this outer wrap has been key so that your eye can travel and you only come upon the detail when you move along the paths or stumble upon it. Sanguisorba ‘Cangshan Cranberry’, perhaps the best of the lot for its finely divided foliage, picked up where I broke the flow of the ‘Red Thunder’ and, where variation was needed, Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires’ has proved to be tireless. Smattered pinpricks, bright mauve on close examination but thunderous and moody at distance, are right for the feeling I want to create and allow you to look through and beyond.

Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’

Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’

Sanguisorba ‘Cangshan Cranberry’

Sanguisorba ‘Cangshan Cranberry’

Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires

Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires

The gauze has been broken by plants that draw attention by their colour being brighter or sharper or the flowers larger and allowing your eye to settle. Sanguisorba hakusanensis (raised from seed I brought back from the Tokachi Millennium Forest) with its sugary pink tassels and lush stands of Cirsium canum, pushing violet thistles way over our heads. The planting has been alive with bees all summer, the Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’, now on its second round of flower after a July cutback, and the agastache only just dimmed after what must be over three months ablaze. Agastache ‘Blackadder’ is a plant I have grown in clients’ gardens before and found it to be short-lived. If mine fail to come through in the spring, I will replace them regardless of its intolerance to winter wet, as it is worth growing even if it proves to be annual here. Its deep, rich colour has been good from the moment it started flowering in May and, though I can tire of some plants that simply don’t rest, I have not done so here.

Sanguisorba hakusanensis

Sanguisorba hakusanensis

Cirsium canum (centre) with Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires and Agastache ‘Blackadder’

Cirsium canum (centre) with Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires and Agastache ‘Blackadder’

Agastache ‘Blackadder’

Agastache ‘Blackadder’

The lighter flashes of colour amongst the moodiness have been important, providing a lift and the key into the brighter palette in the plantings that will be going in closer to the house in a fortnight. More on that later, but a plant that will jump the path and deserves to do so is the Nepeta govaniana. I failed miserably with this yellow-flowered catmint in our garden in Peckham and all but forgot about it until I re-used it at Lowther Castle where it has thrived in the Cumbrian wet. It appears to like our West Country water too and, though drier here and planted on our bright south facing slopes, it has been a truimph this summer.

Nearly all the flowers in the planting here are chosen for their wilding quality and the airiness in the nepeta is good too, making it a fine companion. I have it with creamy Selinum wallichianum, which has taken August and particularly September by storm. It is also good with the Euphorbia wallichii below it, which has flowered almost constantly since April, the sprays dimming as they have aged, but never showing any signs of flagging.

Nepeta govaniana

Nepeta govaniana

Selinum wallichianum

Selinum wallichianum

Calamintha sylvatica ‘Menthe’

Calamintha sylvatica ‘Menthe’

I have rather fallen for the catmints in the last year and been very successful in increasing Nepeta nuda ‘Romany Dusk’ from cuttings from my original stock plant. I plan to use the softness of this upright catmint with the Rosa glauca that step through the beds to provide another smoky foil.

Jumping the path and appearing again in the planting that will be going in in a fortnight are more of the Calamintha sylvatica ‘Menthe’. True to its specific name, this pretty, white calamint seems happy to seed around in cool places and I have used it, as I have the Eurybia diviricata, as a pale and cohesive undercurrent. They weave their way through taller groupings to provide an understory of lightness, breathing spaces and bridges. Both of these are on the autumn order and will jump again into the new palette I have assembled to provide a connection between the two.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 14 October 2017

The various utensils, paper bags and home-made envelopes that have been accumulating all summer were grouped together recently for examination. I find it hard to resist when seed is there for the taking and it is something that I want or could do with more of. If I am lucky and have had a pen handy, the makeshift envelopes are scrawled with notes to make identification easy. The unmarked vessels might need a rattle and a closer look to remind me, but the excitement of a haul usually burns the find into the memory, as long as I act before winter blurs the clarity of this past growing season.

Fortuitously, autumn is the best time to sow the hardy plants and I would rather have them in the cold frame, labelled up and ready to go than degrading and waiting until the spring. In the wild, seed will start its cycle within the same growing season, so emulating the natural rhythm makes perfect sense. Most seed will now sit through the winter to have dormancy triggered by the stratification of frost, but some will seize the damp and comparative mild of autumn to germinate before winter and begin their grip on life.

The giant fennel are a good example. In the Mediterranean and Middle East where they are dependent upon the winter rainfall for growth, summer-strewn seed is now germinating with the first rains. My own sowings from August have already produced their second true leaf and are now potted on in long toms so that they can continue to establish their strong tap roots in the mild periods ahead of us. The winter green of Ferula communis (main image) is remarkable for this late season regeneration, gathering strength when it isn’t too cold and pushing against the general retreat elsewhere.

Sowing seed of Ferula communis in Autumn

Sowing seed of Ferula communis in Autumn

Seedlings of August’s sowing of Ferula communis in the cold frame

Seedlings of August’s sowing of Ferula communis in the cold frame

I first saw giant fennel in my early twenties when I was a student at the Jerusalem Botanical Gardens. Michael Avishai, the Director, had driven me to the Golan Heights to see them in the minefields where they grew freely and undisturbed. We stood at the roadside, taking heed of the sign saying ‘DANGER MINES! Go no further.’ Mile upon mile of cordoned-off ground, back-dropped by the mountains of Syria, was populated by a legion of uprights which bolted skyward in a scoring of perfect verticals. You understood why the Romans had used them as ferules, their stems making a lightweight measuring rod. Amongst their feathery mounds of basal foliage, a flood of acid-green euphorbia and scarlet anemone scattered the rocky ground between them.

You need open ground and the room to be able to let giant fennel have its reign in the garden. Whilst the plants are gathering strength, the early foliage needs the air and light they are accustomed to. Once they have bolted all their energy into the lofty flower stem, the foliage withers to leave a space, so you need to plan for a companion such as Ballota pseudodictamnus that can take a little early shade, but will cover for the gap in high summer.

I first flowered Ferula tingitana ‘Cedric Morris’ in my garden in Peckham and brought seed from there to here. It is the first of several giant fennels to have flowered here and did so in its third year after planting out. This lustrous form of the Tangier fennel is spectacular for its early growth, which is as shiny as patent leather, but finely-cut like lace. The flowering stem, which is shorter than F. communis, which can grow to 3 metres, holds an inflorescence that is just as flamboyant, despite reaching just half that height. My plants originally came from Beth Chatto where it appears in her gravel garden and this is how they like to live, with guaranteed good drainage in winter. I mean to ask if she was given the plant by the great man himself, for I am amassing quite a number of his selections and enjoy the connection of these horticultural hand-me-downs.

Ferula tingitana ‘Cedric Morris’ flowering in late May

Ferula tingitana ‘Cedric Morris’ flowering in late May

Coincidentally, I was given a brown paper bag with ‘Ferula tingitana blood’ scrawled on it by one of the gardeners from Great Dixter at a lecture that I gave for the Beth Chatto Education Trust earlier this summer. It is one of several ferula that Fergus Garret has passed on to me over the years. He too is under their spell and has given me seed of several of his wild collections from his homeland in Turkey. Once, when I asked him what the mother plant was like, he said, ‘No idea. It’s bound to be good though. Try it !’. And with giant fennels I am very happy to take him on trust.

Fergus uses them as punctuation marks in the garden where they bolt above moon daisies and rear over the hedges like giraffes. They have started to hybridise there and, when they are established enough to plant out next spring, the ‘tingitana blood’ seedlings are destined for my new planting. The secret to growing them successfully is to plant them out before the long tap roots wind around the pot for, to support the huge flowering stem, they need their purchase deep in the ground like a skyscraper needs its footings.

A hatful Ferula communis seed gathered in Greece

A hatful Ferula communis seed gathered in Greece

This summer, whilst on holiday in the Dodecanese, I collected a hatful of Ferula communis that had flowered beside the road and somehow escaped the ravages of the island goats. Though I had not seen it in flower, it was impossible to pass it by and the thought of it reappearing as a memory in the garden here will allow me to relive this find when it comes to flower. The seed left after my own sowing is now sitting in a bag waiting to go to Fergus, with a scrawled message of well wishes and the happy thought that they will soon be on their way to another good home.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan & Dan Pearson

Published 7 October 2017

Michael Isted is the founder of The Herball, a company producing handmade herbal infusions and plant extracts in small batches. The plants he uses to produce them are sourced from a number of independent, organic producers and freshness and quality are of prime importance. Michael started out as a drinks specialist and is a trained phytotherapist and nutritionist. He is passionate about educating and celebrating the ways in which we can integrate plants into our diets to energise, enhance and heal.

Michael, you have a background in the beverage industry. Can you tell us how you came to see the importance of plants and how that inspired you to start The Herball ?

I was always fascinated with nature growing up as a child in the cradle of the South Downs in Sussex, picking blackcurrants and sticking cleavers to people’s backs. Then, whilst working in the beverage industry as a drinks consultant, I realised that everything (almost everything) I was working with was made from plants, whether working with gin, vermouth, tea, coffee or distilling eau de vie. I knew I had to dedicate more of my time to learning from plants and from people that worked with plants. It all happened fairly organically, nature called and it felt like a brilliant path to tread, intuitively right.

Where did your passion for plants come from? Are there any key people, influences or experiences that set you on this path?

I think we all have a passion for nature, it’s just sometimes hard to access or connect with nature, particularly in our urban environments, but I’m sure inside of us all is a burning desire to be with nature in some form. Plants are so diverse, colourful, vibrant and dynamic on so many levels. They are extremely influential companions.

Although I didn’t know it at the time, my earliest inspiration were the roses growing on the pathway leading up to our childhood house. That scent has stayed with me forever. The rose is a very powerful plant, it triggers so many memories. Like a form of time travel, it has taken me to some very magical times and places, it has been hugely influential.

Then I was inspired by learning about distilling plants with an eau de vie distiller in Alsace and connecting with herbalists such as Peter Jackson Main, Peter Conway, the work of Barbara Griggs and for sure the writing of Stephen Harrod Buhner. I urge everyone to read his book The Lost Language of Plants.

Dehydrator trays containing (clockwise from top left) dried nettle, cleavers, equisetum, elderflower and gingko.

Dehydrator trays containing (clockwise from top left) dried nettle, cleavers, equisetum, elderflower and gingko.

Photo: Susan Bell

You are a qualified Phytotherapist. Can you explain what that means and what the training involves?

It’s a posh term for a herbalist, to make us sound more professional. It means somebody who works with plants to heal and nurture people. We introduce nature and look at ways in which plants can help support disease, illness or just enrich people’s lives.

I trained with many naturopaths, nutritionists, herbalists and plant workers on shorter courses and then went into a full time BSc (Hons) degree at the University of Westminster. It took four years of full time training, but some of the most valuable training is spending time with the plants themselves. They can teach you a great deal.

Tell us about the range of products you produce, and the process you went through to develop them.

It all started as I was unhappy with the quality of the herbs & spices in many herbal teas and commercial spice ranges. There was (is) a distinct lack of relationship between people and the plants that they are drinking or eating. Supermarkets are littered with herbs in tea bags and boxes, but you don’t see the plants or engage with them enough. You don’t know where they are from, when they were harvested, who harvested them, you can’t even see the plants. So I wanted to create a range of plant products where you could really engage with the plant itself, on a very basic level by looking at and identifying it, drinking its qualities. It’s about engaging with and respecting nature really. I want people to see the love and hard work (from both the plant and the people producing them) that goes into nurturing, growing, harvesting, drying and blending the herbs.

We take plants for granted most of the time. Just take black pepper for example. In almost all households it is just a commodity. It’s just not celebrated enough. It’s a sensational plant, with brilliant flavour. Just take a good quality black peppercorn and place it in your mouth and eat it. Taste it fully and consider its qualities. Phenomenal.

We really want people to engage with the nature that they are drinking, eating and ingesting. All of our plants are harvested in that growing year, we know when they were harvested and by whom. We make our infusions, waters and bitters in tiny batches. It’s all created by hand with lots of care using the most vibrant plant material possible.

The Herball’s Of Aromatic Waters

The Herball’s Of Aromatic Waters

Our aromatic waters (non-alcoholic distillations of plants) were sourced from two distillers in the UK and India, although we have since stopped working with them as we are now distilling everything ourselves. There will be some very special distillates available in 2018 as we are currently working on polypharmic distillations, distilling lots of different plants at the same time. There is a natural synergy between plants in the wild and it’s always interesting to see which plants like to grow together, for example nettle & cleavers. We are trying to capture this synergy and relationship in the form of a distillation.

We distil plants in traditional copper alembic stills (main image – photo by Susan Bell) to use as a flavouring for food and drinks and as ingredients for natural skin care. We are just starting to use CO² extraction, which produces the most beautiful and vibrant oils. We also work with co-operatives in Southern India and Sri Lanka who supply us with beautiful vibrant spices. Again it is crucial that we know who harvested the plants, where and when. We visit the growers on their tiny holdings – when I say tiny they are really tiny, 1 hectare and less – and they cannot afford organic certification, so that’s where the co-operative comes in, to help give the growers the sales platform and access to people like us.

The bitters are remedies and recipes that I had been using in practice and for drinks creation for years. They cover all of my inspirations, so there is an English-based blend with 20 herbs grown here, an Indian blend with spices like cinnamon, turmeric and one of my favourite bitter herbs, Andrographis, and a Chinese blend with Chinese herbs such as Schisandra paired with a beautiful rock oolong tea from our dear friends at Postcard Teas. We wanted to share these formulas with everyone.

From where and how do you source your ingredients?

The herbs we use are mostly grown, nurtured, harvested and dried by a wonderful grower called Diane Anderson who has a smallholding in Oxted, Surrey. Diane was one of my teachers at University. She was an amazing resource and she used to come into the dispensary with the most beautiful dried herbs. Seeing these wonderful dried herbs was also an inspiration to start blending infusions.

We also work with a biodynamic plantation in Somerset, we grow a few things ourselves and for the more exotic plants, as mentioned before, we source from our friends in Southern India and Sri Lanka.

Cardamom

Cardamom

Turmeric

Turmeric

Can you explain how the bitters and herbal waters you produce might be used?

I’m not allowed to talk too much about the health benefits of our products, so broadly speaking their purpose is really to enhance and envigorate drinks and dishes and to give pleasure. The bitters are amazing just with water, or fresh juice, pre- and post-prandial, to stimulate digestive function and assimilate some of the metabolites from your meal. The aromatic waters are so diverse, I use them every day in a glass of water, sprayed directly on my face as a toner (rose), in salad dressings (rosemary & thyme are particularly good), to create cocktails with and without alcohol. They are amazing.

The Herball’s Of Ayurveda Bitters

The Herball’s Of Ayurveda Bitters

Can you tell us something of the therapeutic effects of some of your key ingredients?

Plants have endless therapeutic qualities on so many levels, physically, spiritually, emotionally, and I think it’s important that you are ingesting some good quality organic plants every day. I don’t want to say as part of a routine as that sounds boring, but use them prophylactically as a preventative. Have fun with plants, get to know them, enjoy their nature, enjoy their brilliance, it’s so rewarding for health and happiness.

The herbs we use and work with are packed full of complex secondary metabolites, diverse plant chemicals (phytochemicals) produced by the plants which enable the plants to interact with their environment. These phytochemicals have a wide range of functions, including protection from herbivores, to fight against infections and to attract pollinators such as bees and other insects. The plant’s secondary metabolites include constituents such as tannins, aromatic oils, alkaloids, resins and steroids. It is these chemicals that not only carry a raft of potential health benefits for us, but also offer a huge palette of flavours, textures and aromas to create delicious food and drinks.

The Herball’s Of Herbs infusion contains marshmallow, peppermint, red clover, wormwood, burdock, lemon balm , rosemary, yarrow, goats rue and fennel

The Herball’s Of Herbs infusion contains marshmallow, peppermint, red clover, wormwood, burdock, lemon balm , rosemary, yarrow, goats rue and fennel

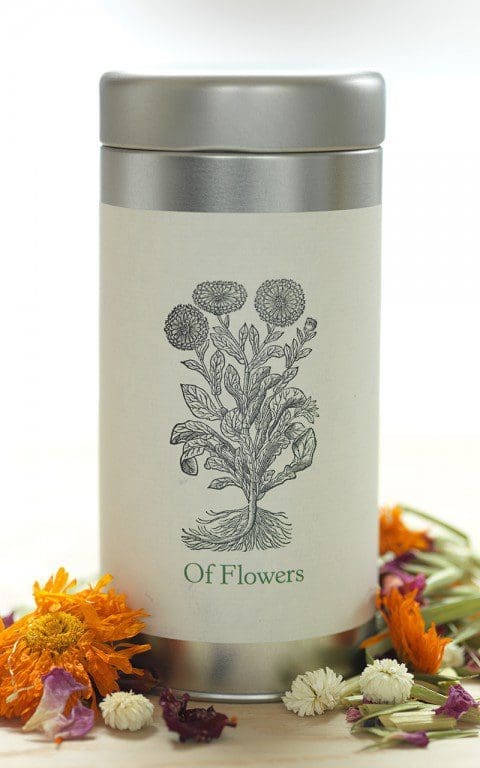

The Herball’s Of Flowers infusion contains oat straw, Roman chamomile, calendula, rose, lavender and goldenrod

The Herball’s Of Flowers infusion contains oat straw, Roman chamomile, calendula, rose, lavender and goldenrod

You have a book coming out in the new year. Can you tell us a bit about it?

Super exciting, yes. It’s a book on my work really. I talk about my inspirations, some of the plants that I work with, when and how to harvest them and then how you can work with those plants to create dynamic and delicious botanical drinks. I talk about distillation, extraction methods, drying and processing the plants and then there are over fifty recipes, all without alcohol.

Would you share a recipe with us that readers can try at home?

Sure. I’m drinking a lot of sage right now so here is a simple recipe with sage including a quote from John Gerard, whose work we have been greatly inspired by, he wrote (or collated and published) the seminal text The Herball or Generall historie of plantes, 1597.

THE WISE ONE

‘Sage is singularly good for the head and brain, it quickeneth the senses and memory, strengtheneth the sinews, restoreth health to those that have the palsy, and taketh away shakey trembling of the members’. John Gerard 1545 – 1612.

Photo: Susan Bell

Photo: Susan Bell

This is a contemporary take on a classic sage preparation to produce a cooling, blood cleansing formula, which makes for a sensational afternoon tipple.

Plants & Ingredients

Sage Salvia officinalis

Lemon Citrus limon

Sugar Saccharum officinarum

Water

Recipe

15g fresh sage

4 lemons

500ml hot water

75ml lemon & sage sherbet (see below)

100g sugar

Method

Boil the water, then pour over 10g of sage into a pot with a lid. Infuse with the lid on for 30 minutes before straining into another jug or decanter. Peel 1 of the lemons and keep the zest. Add the juice of that lemon and the sherbet to the decanter and stir until dissolved. Keep the jug or decanter in the fridge to chill and serve once cold.

Serve in a wine glass with the remaining twist of lemon and fresh sage leaves

For the Sherbet

Peel the remaining 3 lemons, then put the zests in a container with the sugar and the remaining 5g of sage. Press the zests with the sugar and sage for a minute or so, then juice the lemons and stir the juice into the sugar mixture. Seal and leave to infuse overnight, or for at least 6 hours. Stir, strain and bottle. This will keep refrigerated for at least 1 month and can be enjoyed with still and sparkling water.

The Herball’s Guide to Botanical Drinks: A Compendium of plant-based potions to Energise, Cleanse, Restore, Boost Sleep and Lift the Heart by Michael Isted, photography by Susan Bell, will be published by Jacqui Small in February 2018. Pre-order here.

Twitter: @TheHerball

Instagram: theherball

Interview: Huw Morgan/All other photographs: Laura Knox

Published 30 September 2017

For the first three or four years here we grew row upon row of dahlias in the old vegetable garden. They soaked up the light in the first half of summer and flung it back again in a riot of colour later. We grew upwards of fifty, with rejects making way for new varieties from one year to the next to test the best and the most favoured. The dahlias were completely out of character with what I knew I wanted to do here but, like children in a sweetshop, we had the space to play and so we indulged.

Three years of experimentation left us gorged and satiated, but a handful made it through to become keepers. All singles, and delicate enough to be worked into the naturalism of the new planting, we kept Dahlia coccinea ‘Dixter’ for sheer stamina of performance, Dahlia merckii ‘Alba’, the most delicate of all, and the demurely nodding Dahlia australis. Proving to be perfectly hardy with a straw mulch as insurance against the cold they have made good garden perennials. The exception is a scarlet cactus dahlia that outshone the blaze of competition in the trial. Originally bought as ‘Hillcrest Royal’, but mis-supplied, we grew it in our old garden in Peckham and loved it enough to bring it with us and, then again, to keep it in the cutting garden. Unable to identify it correctly after many years of sleuthing we named it ‘Talfourd Red’ after the south London road we lived on and I cannot imagine an autumn now without its flaring fingers.

Dahlia ‘Talfourd Red’ and Dahlia coccinea ‘Dixter’

Dahlia ‘Talfourd Red’ and Dahlia coccinea ‘Dixter’

I do like a new plant, and getting to know Tithonia rotundifolia for the first time this year is enabling me to see how it might be used to inject some late summer heat into a planting. We already have a handful of favourites here that are tried and trusted and loved for their intensity of colour, which builds as the growing season wanes. In the case of the Tropaeolum majus ‘Mahogany’, they are almost at their best sprawling and vibrant in the damp cooling days and allowed to climb into their neighbours. The seed originally came from the garden of Mien Ruys at least twenty years ago. I had gone with two friends on an inspirational trip to see what was happening in naturalistic gardens in Holland and Germany and we stopped to meet her in her wonderful garden. The seed was scattered on the pavement over which it was sprawling and a few found their way, with her consent, into my pocket.

This ‘Mahogany’ is not what you will get if you look for it in the seed catalogues. Indeed, it now seems to be unavailable apart from in the United States and ‘Mahogany Gleam’ is a different thing altogether. The leaves are a brighter more luminous green than usual and the flowers a jewel-like ruby red. I have been territorial ever since I started to grow it and winkle out any that come up with a darker leaf or paler flower. It self-seeds willingly every spring, letting you know when the soil is warm enough to sow and where the warmest parts of the vegetable garden are. The seedlings exhibit the same bright foliage so it is easy to weed out the occasional rogue, which might have reverted to the darker more typical green. We currently grow ‘Mahogany’ in the kitchen garden amongst the asparagus and use the leaves and flowers to garnish salad.

Tithonia rotundifolia ‘Torch’

Tithonia rotundifolia ‘Torch’

Tropaeolum majus ‘Mahogany’

Tropaeolum majus ‘Mahogany’

Close by, and growing this year in two old stoneware water filters, is Tagetes patula. This wild form will grow up to three or four feet with a little support or something to lean on and flowers from June until it is frosted. The colour is absolutely pure and as vibrant and saturated a saffron yellow as you can find. It is easily germinated from seed under cover in spring and fast, so best to wait until mid-April to sow. I harvest my own seed and keep it apart from the dark, velvety Tagetes ‘Cinnabar’ (main image), which it will taint. Seedlings that have crossed will no longer have the deep richness that makes this latter plant so remarkable. I was disappointed to find this spring that the mice had eaten all the seed I’d left out in the tool shed and was expecting to have the first of many years without it. However, as luck would have it and quite out of the blue, they somehow found their way some distance into the new herb garden. Maybe it was mice doing me a favour with the plants I left standing in the kitchen garden last winter. Another lesson learned.

Tagetes patula

Tagetes patula

Tagetes ‘Cinnabar’

Tagetes ‘Cinnabar’

Pelargonium ‘Stadt Bern’

Pelargonium ‘Stadt Bern’

My father was never afraid of colour and always commented on the brilliance of Pelargonium ‘Stadt Bern’, which is the best, most brilliant red I have ever come across. Purer for the flowers being properly single, with elegant tear-shaped petals and thrown into relief against darkly zoned foliage. I bought a tray of plants from Covent Garden Market twenty five years ago for my Bonnington Square roof garden and have managed to keep them going ever since. Given how archetypal it is for a pot geranium I have no idea why it is not more freely available, but there are always a handful of cuttings in the frame which are for giving away to friends, who are given these precious things on the understanding they are part of keeping a good thing going, and that they are my insurance for any unexpected losses.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 23 September 2017

A month ago I was in Japan, on my annual visit to the Tokachi Millennium Forest in Hokkaido. I have been working at the forest for sixteen or seventeen years now and the yearly journey is always rewarding. It is a place with a big vision, where half the side of a mountain and the forested foothills are the domain. It has the feeling of the north, with air that slips over the mountains from Russia not so far away. Bears really do live in the woods and the landscape freezes to minus twenty-five, under a blanket of pristine white from early November through to the end of April.

The owner, Mitsugishe Hyashi, bought the land with the ambition of offsetting the carbon footprint of his newspaper business, but the park represents far more than this. He also set out for it to be sustainable for the next thousand years and it is a privilege to have been part of this vision and to be a small part in shaping the park’s direction.

The gardens and the managed forests are a big part of helping to communicate the big idea to visitors. The gently managed places, which take the rough edges off the wilderness, are part of making people feel comfortable in the areas that are accessible. Takano Landscape Planning, which put together the original masterplan, knew that the people and their comfort in the environment were important and, when I was asked to be part of the project in 2000, it was to help with creating a series of spaces that would provide the landscape with a focus for the public.

The Earth Garden

The Earth Garden

The Goat Farm and Farm Garden at the end of the Meadow Garden

The Goat Farm and Farm Garden at the end of the Meadow Garden

The Rose Garden

The Rose Garden

In their turn, the gardens we have since created have been key in making a ‘safe’ place and a link with the magnitude of the landscape, to literally ground the visitor in the place. A landform called the the Earth Garden, which reconfigured a clearance field that separated the visitor from the mountains, was the first of the projects to come to fruition. A series of grassy waves, echoing the undulations of the mountains beyond, now provides the visitors with a ‘way into’ the landscape. By exploring the earthworks they soon find themselves at the base of the mountains or at the edge of a mountain stream or a trail into the woods. The landforms extend to wrap another five hectares of cultivated garden, and area named the Meadow Garden, which was planted to celebrate the official opening ten years ago. Beyond that there is the Farm Garden where people can see a modestly-sized productive space with fruit, vegetables and cutting flowers and eat food grown there at the cafeteria. A goat farm producing cheese is the backdrop to this space, while most recently we have developed a Rose Garden of hybrid and species roses suitable for a northern climate and an orchard to test growing apples and other top fruit this far north.

The Entrance Forest

The Entrance Forest

The Entrance Forest, where Fumiaki Takano had already made a start when I was brought on board, eases visitors in with soft bark paths and decked walkways that take them back and forth across the rush of mountain water that switches between the trees. The low native bamboo Sasa palmata, which took over the forest after its balance was disturbed when all of the oak was logged at the turn of the last century, has been carefully managed to encourage a more diverse regeneration of the forest floor. Repeated cutting in the autumn, coupled with the short summers that curtail its regrowth and stranglehold, has been diminished enough for the window of opportunity to be given back to other plants in the native seedbank. Wave upon wave of indigenous plants now greet the visitors. Anemone, Caltha palustris var. nipponica and Lysichiton camtschatcense seize the window after snow melt and, as oak woodland comes to life, the race continues with Trillium, scented-leaved and candelabra primulas and arisaema. By the time I arrived in late July, the woodland was tall with giant-leaved meadowsweet, cardiocrinum and lofty Angelica ursina.

Lysichiton camtschatcense

Lysichiton camtschatcense

Filipendula camtschatica

Filipendula camtschatica

The Meadow Garden (main image), my primary focus with Head Gardener, Midori Shintani, was inspired by the woodland and the way the plants have found their niche and live together in successive layers of companionship. Sitting on the fringes of the wood where dappled light meets sunshine, it is divided into two main parts by a meandering wooden walkway. The lower areas emulate the edge of woodland habitats, while above the path the planting basks in full sunshine. The planting is further divided by swathes of Calamagrostis x acutiflora ‘Karl Foerster’, which separate the different colour fields, so that the yellows are held back as a surprise. The movement of the mountain winds is caught in their plumage to animate the garden.

The plantings integrate Japanese natives with plants from other regions of the world that have similar climates. North America and parts of northern Europe provide the ‘exotic’ layer in the garden and their inclusion draws attention to the Japanese natives that are mingled amongst them. Plants such as the Houttuynia cordata, Hakonechloa macra and Aralia cordata. Everyday plants in Japan that are given a new focus. In terms of my own gardening process, these plants were the exotics and it has been such a fascinating process to reverse my experience of the exotic/native balance. Native Lilium auratum, the Golden-Rayed Lily of Japan, and the giant meadowsweet, Filipendula camtschatica, are teamed with Phlox paniculata ‘David’. Sanguisorba hakusanensis, the extraordinary pink, tasselled burnet is in company with Valeriana officinalis and Astrantia major ‘Hadspen Blood’.

The woodland edge of the Meadow Garden with ground cover of Hakonechloa macra and Houttuynia cordata

The woodland edge of the Meadow Garden with ground cover of Hakonechloa macra and Houttuynia cordata

The woodland edge of the Meadow Garden with Lilium auratum and Phlox paniculata ‘David’

The woodland edge of the Meadow Garden with Lilium auratum and Phlox paniculata ‘David’

Sanguisorba hakusanensis, Astrantia major ‘Hadspen Blood’ and Valeriana officinalis

Sanguisorba hakusanensis, Astrantia major ‘Hadspen Blood’ and Valeriana officinalis

The original planting plans were designed as a number of individual mixes, planted in drifts to allow the planting to flow across the site. Each mix contained a small number of species, usually five to seven, that were planted completely randomly. The percentages in the mix were critical, with a small number of emergent plants such as the Cephalaria gigantea to rise above larger percentages of individuals that would knit and mingle at lower and mid-level. Now that I look back it was a brave move, because it was entirely dependent upon the head gardener to steer and monitor.

Midori has been more than I could have hoped for in an ally on the ground and our yearly critique and analysis of the plantings is a high level conversation that looks both at the big picture and also at the detail. Of course, there have been adjustments to refine each mix as they change yearly with plant lifespans, climate and vigour, which drive our response. But we have also needed to make changes to keep the garden moving forward, introducing new plants and swapping or reducing the numbers of those which have become dominant. For instance, we have found plants that will happily coexist in a demanding matrix of twenty five companions in the wild, can take their opportunity to dominate when given just a handful of company.

Persicaria polymorpha and Gillenia trifoliata

Persicaria polymorpha and Gillenia trifoliata

Dan placing new additions of Lilium henryi with Head Gardener, Midori Shintani

Dan placing new additions of Lilium henryi with Head Gardener, Midori Shintani

Last year, to challenge the thousand year brief of sustainability, a tornado swept across the island. It hit last summer, just before I visited and I arrived to see the carnage. The mountain water had swelled the streams that braid the site to rip and tear and deposit a silver sand from afar and boulders that are now new features. Miraculously the waters divided to either side of the Meadow Garden, but they swept away all but two of the bridges, which have never been found. We were left feeling very small and of little consequence within the time frame that had been set for the preservation of this place.

The repairs have been slow but sure and in scale with what is possible. New shingle banks have been embraced as the new places and opportunities that they are. Already they are being colonised. It is the gardener’s way to repair and to move on, but we have been humbled nevertheless. Midori walked me through the garden, pointing out ‘weeds’ that have been swept in to the planting that were never there before. And there are anomalies that are hard to get to grips with that point to changes of another scale. Some plants have taken a hit a year later to sulk or fail, and we do not know why, whilst others have seized life with a new vigour as if the charge from the mountain has revitalised them. With ten years under our belts and the knowledge we have gained that is specific to this place, we are adjusting again and moving on. On to a second decade and the certain changes that we will be responding to, to move with it.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Kiichi Noro and Syogo Oizumi

Published 16 September 2017

One of the best things about growing your own fruit and vegetables is the opportunity it provides to eat things that are seldom, if ever, available at the greengrocers. Before we planted our orchard I had never eaten a Mirabelle plum. Although I had pored over Jane Grigson’s description of their superior flavour, and heard from my Francophile friend Sophie of the delicious tarts and pies she had eaten in Lorraine, I had always had to imagine what they tasted like.

The Mirabelle is the smallest plum, barely bigger than a large marble, but what it lacks in size it definitely makes up for in flavour. Perfumed, and with the same floral hint of muscat that you get from the best gooseberries, they are the plum par excellence. We are now getting a very decent harvest and, when something so rare and prized suddenly becomes easily available, it feels important to celebrate the moment with a dish that makes the most of this fleeting moment.

You need a fair number of Mirabelles to make a tart of this size, but they are quick to pick. De-stoning a large bowl of them also appears an intimidating prospect but, being a ‘freestone’ variety of plum, where the stone separates easily from the flesh (unlike ‘clingstone’ plums where the flesh adheres to the stone) they are also easy to prepare.

Plums and almonds are all from the Prunus family, and so make perfect companions in in desserts. The flavour of the almond frangipane is improved by the addition of a number of kernels taken from the stones, which enhances the bitter almond flavour, but a few drops of almond essence or, if you happen to have it, a teaspoon or two of plum eau de vie do a similar job.

The Mirabelle season is painfully short. The tart here was made last weekend, when the plums were at their peak of perfection. This week the tree is bare. So, if you have missed the moment or can’t get hold of them, you can use any other stone fruit in their stead. Greengages are the next best choice of plum, but other yellow cooking plums would work, as would apricots. Later in the season the frangipane can be made with ground walnuts, which makes a more autumnal partner for sharp red or purple plums. This year I plan to try a walnut version with some of our damson glut but, being mouth-puckeringly sharp, they will need to be poached in a sugar syrup first.

Mirabelle de Nancy

Mirabelle de Nancy

INGREDIENTS

500g Mirabelle plums, stoned and halved (weight after stoning)

Pastry

300g plain flour

150g unsalted butter, well chilled

3 tbsp icing or caster sugar

1 egg yolk, beaten

Iced water

Almond Cream

150g ground almonds

150g caster sugar

150g butter, melted

1 large egg, beaten

2 tbs double cream

Kernels from about 20 Mirabelles

Serves 12

METHOD

You will need a 30cm shallow, fluted tart tin.

Set the oven at 180°c.

Put the flour and butter into a food processor and process quickly until the mixture resembles very fine breadcrumbs. You can use your hands to do this, but a processor is better as it is important that the pastry stays as cold as possible. Add the icing sugar and pulse again quickly to combine. With the motor running add the egg yolk, and then enough chilled water, a tablespoon at a time, until the dough just starts to come together. Immediately turn off the processor and bring the dough together quickly and lightly with your hands until smooth. Do not knead it.

Immediately roll the dough out, preferably on a cold, floured slate or marble surface, with short, light movements until just large enough to line the tin. To get the pastry, which is very short, into the tin, ease your floured rolling pin underneath it and then very gently lift it over the tart tin until it is centred, before removing the rolling pin by sliding it out. Again handle the pastry very gently as you press it into the corner and fluted sides of the tin. Trim the pastry in line with the top of the tin, prick the base with a fork and then chill in the fridge for 20 minutes.

Remove the pastry case from the fridge, line it with baking parchment and then fill with baking beans. Bake blind for 20 minutes. Remove the baking beans and parchment and return to the oven for a further 10-15 minutes until the pastry looks dry but has not coloured. Remove from the oven and leave to cool.

Turn the oven up to 200°c.

Put the ground almonds and sugar in a mixing bowl, reserving a tablespoon of sugar. In a mortar and pestle crush the Mirabelle kernels with the tablespoon of sugar then add them to the ground almonds, before mixing in the butter, egg and cream.

Spread the almond cream evenly over the base of the cooled tart case. Then, starting from the outside, arrange the Mirabelles on the almond cream with their cut sides facing up and so that they are just touching. Push each one gently into the cream as you do so.

Bake for 30-40 minutes, until the pastry is well coloured and the mirabelles are bubbling.

Remove from the oven. Allow to cool for 15 to 20 minutes before carefully removing from the tart case.

Serve warm with cold pouring cream.

Recipe and photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 2 September 2017

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage