The Thalictrum ‘Elin’ are as spectacular as they ever will be, topped out at what must be almost ten feet in height and clouding a myriad of tiny flower. They are in their second year now and have been good from the day they broke their winter dormancy. Last year they sent up just a couple of spires each but, with roots deep and a year behind them, they have powered a forest of lustrous growth. First, an early mound of feathery foliage of a glaucous, thunderous grey flushed with purple and bronze which, by the end of April, had reached its full expansion and was ready to charge the ascent of muscular vertical stems soaring towards the solstice. Slowing once they had reached their full height, the panicles broadened as the lateral limbs filled out with a million buds. The ascent was every bit as remarkable as the cloud of smoky violet flower. Arguably more so for the dramatic build and anticipation.

‘Elin’ march through the planting in the lower part of the garden to provide punctuation, and I am depending upon them now to stay standing. Last year, when their limbs were heavy with flower, a rain-laden wind toppled them like ninepins, so I staked them with a waist-height hoops in early May to prevent a repeat performance. In our deep, hearty soil with plenty of sunshine and no early competition around their crowns, there has been nothing to hold them back, so I have grown them hard and so far denied them extra water. I am hoping this will mean that they grow more strongly and that their companion sanguisorbas help them to stay true.

Thalictrum ‘Elin’

Thalictrum ‘Elin’

I have grown Thalictrum aquilegifolium for years, where it is reliable in both sun or shade. A basal clump of foliage – well named for its similarity to columbine – is an early presence in the spring garden and the flowers are sent up early, ahead of most other perennials, so that there is a clear storey between them and their foliage. The wiry stems support clusters of stamen-heavy flowers which, when they are out, resemble exotic plumage. In the true species, the flowers are an easy mauve, but ‘Black Stockings’ (main image with Salvia nemorosa ‘Amethyst’ and Iris sibirica ‘Papillon’) punches the colour up, with dark-stained stems and buds the colour of unripe grapes that open into flowers that register strong violet-pink. I have the white form too, which is strangely rare in cultivation, but not impossible to get. My plants came from the Beth Chatto Nursery, but I will be saving seed, which is viable if sown fresh, and I’m hoping will come true as they are quite some distance in the garden from their cousins. Seedlings that aren’t true white will easily be spotted for they have the purple stain, when the white form is pale, apple green. I plan to have plenty to play with and want to see if they will take in some open ground under the crack willow, where I let the Galium odoratum loose after it misbehaved and took too well to the garden.

Thalictrum ‘Black Stockings’

Thalictrum ‘Black Stockings’

Until ‘Elin’ appeared on the scene relatively recently, Thalictrum rochebruneanum was the tallest and most dramatic of the tribe. I saw it first at Sissinghurst, where it towered with Cynara in the purple border. As a teenager I lusted after its rangy limbs, impossibly fine it seemed, and the suspense in the delicate flowers. It languished on our thin acidic ground in my parents’ garden, growing to half the height. I tried it again in the Peckham garden, but it hated the way our soil dried as the water table dropped in summer. However, I have grown it well in California where, with a little extra water and shade from the sun, it seeds freely to spring up spontaneously as ‘volunteer’ seedlings. I hope that it will do the same for me here. So far in year two, it has done well, certainly not as well as ‘Elin’ but, with three or four flowering stems per plant, which have enjoyed the light at the base where they have been planted amongst later-to-emerge persicaria.

Thalictrum rochebruneanum

Thalictrum rochebruneanum

Hailing from Japan, where they find a niche amongst other perennials that like a cool, retentive soil, they must be a spectacular sight to come upon. Where ‘Elin’ is all about quantity, the flowers forming a Milky Way when they come together, every flower of Thalictrum rochebruneanum is a jewel. Richly coloured like gemstones, held sparsely so that your eye is drawn to the individual, inviting you to spend some time to take in the space and the colour contrast of the inner parts of the flower. A cup of violet petals holds the gold provided by the pollen and projection of anther within.

Never getting everything completely as I want it to be, I see now that I need to bring a plant or two up closer to the path, so that I can take in the detail and enjoy looking up, for you have to, your neck craned. Being early days in this garden, I can only hope for a volunteer or two to take to this ground and let me know that I have finally found them a place they really want to be.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 30 June 2018

When I was a child we spent every summer holiday in Wales, staying with my maternal grandparents who lived near Gowerton, the gateway to the Gower peninsula. When the weather was good we would head straight to Horton beach after breakfast, with crab paste and ham sandwiches wrapped in foil, hard-boiled eggs, bags of crisps and a tin of Nana’s homemade Welsh Cakes and pre-buttered slices of Bara Brith to see us through the day.

My grandfather was a Baptist minister, so on Sundays the day started differently. Nana was up even earlier than usual, housecoat on and getting lunch (or dinner as we called it in those days) prepared before we all headed off to chapel. All of the vegetables came from the back garden, which was given over entirely to food; potatoes, runner beans, peas, broad beans, lettuces, onions, beetroot, carrots, parsnips, swedes, cabbages and, of course, leeks. A tiny greenhouse was full to bursting with tomatoes and cucumbers. At the front of the house, the long bed running down one side of the path was filled with Dadcu’s dahlias, tied to bamboo canes in regimented rows, a cacophony of colour in every shape available, like sweeties. On the other side of the path an assortment of exotics planted into the lawn, including a phormium, a bamboo and a pampas grass, provided me and my brother with a playtime jungle.

The chapel was just on the other side of the street so, as soon as the service was over, Nana would head back to the manse to get dinner on the table for Dadcu’s return. Although a full roast dinner was not unusual on these sweltering summer Sundays, the meal I remember most clearly, and which was my favourite, was cold boiled ham with minted new potatoes and broad beans in parsley sauce. I loved the combination of the cold, salty meat, buttery potatoes and creamy beans and would ensure I got a little of each on every forkful.

Thinking back to this garden now I realise that, although Dad also grew veg in our North London garden, it was Dadcu’s kitchen garden where I first really understood the connection between plant and plate. My brother and I would be sent out to help dig potatoes, getting a rush of excitement as the first pearly tubers were heaved from the rich, dark soil, scrabbling to grab them and put them in the bucket. Pulling carrots straight from the ground I would think of Peter Rabbit, although I was sure that, unlike Mr. McGregor, the Revd. Jones did not have a gun. And often I would sit on the back step with Nana and Mum easing broad beans from their pods, marvelling at their cushioned, fleecy protection and enjoying the plonking noise they made as they fell into a plastic bowl at our feet. I never questioned that what we ate at mealtimes had been grown just yards from the dining table, nor that there was work required to get it there. I think that even then those vegetables tasted better to me because they were so fresh and I had helped get them to table.

Broad Bean ‘Karmazyn’

Broad Bean ‘Karmazyn’

Although I can’t profess to be as good a vegetable gardener as my grandfather, now that we have a kitchen garden of our own, I find it hard to buy anything other than lemons, melons or peaches from the local greengrocer in the summer. The feeling of being able to assemble a meal entirely from vegetables you have grown, harvested and prepared yourself has no equal. People say that vegetable gardening is hard work, and I agree, but I don’t understand why this is seen as a negative. The time, care and nurturing that goes into producing your own food gives you a connection to it that is as nourishing as the food itself. When you understand the hard work involved in growing, tending and harvesting you stop taking food for granted and get some perspective on how much food should really cost.

So, to get back to the broad beans. We have grown two varieties this year. An unnamed heritage variety with very decorative, dark pink flowers and green beans from a late autumn sowing, and a variety named ‘Karmazyn’, with white flowers and beautiful rose pink beans, which were sown in March. Surprisingly, the later sown ‘Karmazyn’ have been the quicker to mature. Earlier in the season, as it became apparent that the plants were starting to overtake their autumn-sown neighbours, I was concerned that we were going to have a major glut when both varieties came together, but it now appears we will have a good succession from pink to the green. Close by the artichokes are producing almost faster than we can eat them. ‘Bere’, the variety we grow, is spiny with little meat at the base of the leaves, but the hearts are a good size, sweet and strongly flavoured.

Due to their synchronised production in the garden it is no surprise that broad beans and artichokes are commonly cooked together, with a variety of recipes to be found in French, Italian, Greek, Turkish and other Middle Eastern cuisines. What is common to many of them is the generous use of lemon and fresh herbs. This recipe is very loosely based on an Elizabeth David recipe for Broad Beans with Egg & Lemon from Summer Cooking, which would appear to be of Greek origin. Here the boiled vegetables are dressed with a light, creamy, herb-flecked sauce. A more refined and delicate version of my dear Nana’s beans, although just as good with a couple of slices of cold, boiled ham.

Artichoke ‘Bere’

Artichoke ‘Bere’

INGREDIENTS

Artichokes, 4 small per person

Broad beans, I kg in their pods to yield about 250g

Zest and juice of 1 lemon (reserve 1 tablespoon of juice for the sauce)

Sauce

Butter, 25g

Garlic, a small clove, minced

Cornflour, 1 teaspoon

The yolk of a small egg, beaten

Single cream, 4 tablespoons

Tarragon or white wine vinegar, 1 teaspoon

Lemon juice, 1 tablespoon

Cooking water from the beans, about 200 ml

Fennel, 1 tablespoon finely chopped

Dill, 1 tablespoon finely chopped

Tarragon, 1 tablespoon finely chopped

Salt

Serves 4

METHOD

Bring a large pan of water to the boil. Cook the artichokes for 15-20 minutes until the point of a sharp knife can be easily inserted into the base. Drain the artichokes, run under a cold tap for a moment and then allow to drain and cool completely.

Put the lemon juice in a small bowl. Cut the stalks from the artichokes and gently remove and discard all of the leaves until you reach the choke. Carefully scrape out the choke with the edge of a teaspoon. Tidy the hearts with a sharp knife removing any tough green bits. Rinse in a bowl of water to remove any clinging choke hairs. Dip each heart into the lemon juice as you go and put to one side in a bowl.

Bring a fresh pan of water to the boil. Throw in the beans and cook until just done. Freshly picked ones take only 2 or 3 minutes, older beans will take a little longer and may need to be slipped from their tough outer skins after cooling. When cooked remove 200ml of the cooking water and keep to one side. Then drain the beans and immediately refresh in cold water. Drain and reserve.

To make the sauce, in a pan large enough to take the artichokes and beans, melt the knob of butter until foaming. Take off the heat, put in the garlic and swirl the pan around to cook it lightly and flavour the butter. Still off the heat put in the cornflour and stir well. Add the cream and stir again. Add the egg yolk and stir once more. Then add about 150ml of the reserved cooking water, the vinegar and lemon juice. Season with salt. Put the pan back on a low heat and stir continuously until the sauce starts to thicken. Taste to ensure the cornflour is well cooked and adjust the seasoning. The sauce should be glossy and the consistency of single cream. If it is too thick loosen with some of the reserved cooking water. Put in the chopped herbs and lemon zest and stir through. Put the artichokes and broad beans into the pan and stir gently but thoroughly to ensure that all of the vegetables are well coated with the sauce.

Transfer to a serving dish, and strew some more herbs and lemon zest over the top. Serve warm or at room temperature.

Good enough to eat simply on its own or on toast, this is also a perfect side dish for poached salmon or trout, and cold roast chicken.

You can use any combination of soft green herbs that you have available. Chervil is particularly good, as are parsley and mint. For a more substantial side dish a couple of handfuls of the tiniest, boiled new potatoes make a fine addition.

Recipe & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 23 June 2018

The last few weeks of growth have been remarkable, the volume and intensity lusher for the wet start and the thunderous, still growing weather. In this lead up to summer the garden was texturally wonderful, the layering of foliage acute for the absence or scarcity of flower. Finely divided mounds of sanguisorba, spearing iris and mounding deschampsia all readying themselves, but yet to show colour. A sense of expectation and the build up to the first round of early summer perennials we have today in this posy.

The colour in the garden is designed to come in waves, like a swathe of buttercups in a meadow, that leads your eye from one place to the next and builds in intensity and then dims as the next thing takes over. After an awakening of single peonies, the salvias are the next contrast to the foundation of greens, which I like here for their ease in the landscape. Though I have never found our native Meadow Clary (Salvia pratensis) on the land, it felt right to bring it into the garden in its cultivated form. We have two named varieties which are early to show and good for their verticality. Salvia pratensis ‘Indigo’, a rich, well-named blue and Salvia pratensis ‘Lapis Lazuli’, which was planted last autumn and is flowering here for the first time this year.

Salvia pratensis ‘Lapis Lazuli’

Salvia pratensis ‘Lapis Lazuli’

Where ‘Indigo’ is perfectly named, ‘Lapis Lazuli’ has nothing of the intensity of the stone it is named after, nor of the ultramarine pigment derived from it. I have a nugget on my windowsill which I found once in Greece, sparkling in crystal clear shallows and catching my eye like a magpie’s. Although I was expecting something brighter and cleaner in colour like my find, the clear, soft pink of ‘Lapis Lazuli’ is anything but disappointing. It has been in flower now since early May for a whole three weeks longer than it’s cousin ‘Indigo’, rising up to two feet in widely spaced spires from a rosette of puckered, matt foliage. I expect it to still be looking good at the end of the month, but shortly before it starts to run out of steam, it will be cut to the base to encourage a second flush.

Salvia nemorosa ‘Amethyst’

Salvia nemorosa ‘Amethyst’

The first cut back is always hard, because the salvias are a magnet to moths and bees, but we performed the same severity of cut on ‘Indigo’ last year and it rewarded us with a new foliage and then flower in August. Salvia nemorosa ‘Amethyst’, the second of the salvias in this posy and far better named for it’s jewel-like colouring, will also respond to the same treatment, but it is important to act before the energy has gone out of the plant by curtailing its show before it finishes flowering naturally. Energy put into seed will thus be saved and replaced with more flower and the reward of fresh new growth.

Cirsium rivulare ‘Trevor’s Blue Wonder’

Cirsium rivulare ‘Trevor’s Blue Wonder’

The cirsium and the cephalaria are also encouraged to produce a second round of foliage by cutting them to the base immediately after they flower. Though they are less inclined to throw out more flower, refreshed foliage is just as useful in an August garden, which needs the greens from this early part of the summer to keep the garden looking lively. The Cirsium rivulare ‘Trevor’s Blue Wonder’ in this bunch grows down by the barns, where its early show coincides with baptisia. Though not remotely blue – a theme that is coming through in this posy, it seems – I love the bluer purple of this form just as much as the garnet red of the Cirsium rivulare ‘Atropurpureum’. These early thistles like plenty of light around their basal clump of foliage and look best for having the air you need to appreciate the way their flowers are held high and free of foliage.

Cephalaria gigantea

Cephalaria gigantea

Cephalaria gigantea is similar in its requirements and looks best when it can punch into air without competition. I grow it as an emergent amongst low Coreopsis verticillata ‘Moonbeam’ at the Millennium Forest in Hokkaido, where they grow ten feet tall on either side of a winding path. The creamy yellow flowers are delightfully sparse and the terminus of a rangy cage of airy growth. Here on our hillside they grow six or seven feet at most and right now appear head and shoulders above their partners. A single plant will leave a sizable hole in a planting if you choose to fell it after flowering, as I do for fresh growth, so it is wise to combine it with later performing partners that ease its temporary absence. Asters, grasses and sanguisorba cover for me here.

I have two more species that are part of the new planting and will flower for me for the first time here this year. Cephalaria alpina is a smaller cousin which is more delicate in all its parts, terminating at about four feet and forming a low mound of divided foliage. Cephalaria dipsacoides, teasle-like in its naming and also in its vertical nature, is up to six feet tall, but grows upright from the base. Creamy in colour like its cousins, but differing from all the plants in this posy in being later to flower and prolifically seeding if it likes you. Although I love its seed heads and the structure they offer the autumn garden, I will be cutting the plants down prematurely before they seed. A practice I am having to employ here with several of the self-seeders, as I do not have the manpower to manage the progeny.

Knautia macedonica

Knautia macedonica

A case in point being Knautia macedonica, that I will now treat as a useful filler where I need something fast and reliable. Our ground is almost too rich for this pioneer and in year two the plants splay fatly where they have been living too well. It too seeds prolifically, and my failure to deadhead them last summer resulted in a rash of seedlings this spring, which showed that it could be a problem if left to go native. A few seedlings on standby, however, will provide me with gap fillers where I need them and a succession of this ruby-red scabious that hovers amongst its neighbours. We pull any pink seedlings, favouring the bloodline of those with darker genes.

Stipa gigantea

Stipa gigantea

Stipa gigantea, the Giant Oat Grass is a plant that I have not grown since Home Farm, where it was a mainstay of the Barn Garden. For a while this grass became so fashionable that I avoided using it, despite its obvious beauty and, without enough room to grow it in the Peckham garden, I gave myself a breather. However, I am very happy to have it back and have given it the room it needs to look its best and for its low mound of evergreen foliage to get the light it needs. Right now it is at its most captivating, the lofty panicles, pale copper before turning gold and heavy with yellow pollen, dancing lightly to catch the long evening light. It is an early grass, bolting sky-bound plumes in May and taking June in a shower of luminosity and light.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 16 June 2018

It is that time again, a relay of one spectacle running into the next. In the hedgerows the hawthorns burst and spilled in Hockneyesque flurries, dimming only for a moment before being replaced by guelder rose and now the first of the elder with its creamy tiers piled high. In the garden, where we are working towards a similar principle of massed succession, the Rosa ‘Cooperi’ has helped us to connect to these whites in the landscape and jump the boundaries, so that your eye can travel a distance. First close up and then out, to leap from hedgerow to hillside.

I first saw Rosa ‘Cooperi’ about twenty years ago when I was judging the open gardens of Islington. It was love at first sight and I asked for and came away with a cutting, which rooted readily and took over the wall at the end of the garden in Peckham. It grew there vigorously and now I smart to think what the current owners must be dealing with, because this is a rose that needs headroom. A cutting was dutifully brought to Hillside where I released it onto the old barns (main image) and, seven years later, it is showing not a sign of slowing. Its limbs, reaching continually out and away from the last year’s extension growth, can easily make three to four metres in a season, though it is said to reach no more than ten. As the best flowering wood is the previous year’s, it makes sense to let it advance without curbing it too vigorously, and so it clouds and softens the building’s outline.

Rosa ‘Cooperi’ – Cooper’s Burmese rose

Rosa ‘Cooperi’ – Cooper’s Burmese rose

I keep it from overwhelming the barn – for it has made its way inside as well as out – by cutting back the excess of viciously thorned limbs in winter. You have to tie down your hat, or it will be whipped from your head, and wear tough clothing, never a jumper, which will be laddered and have you snared in moments. Wrangling aside, the dark, glossy foliage is the perfect foil for a succession of simple, ivory flowers that this year smattered in the last week of May and were at their zenith last weekend when these photographs were taken.

In form they are as pure as dog roses, but twice the size, becoming speckled pink if they get rained upon and as they age. The display lasts three weeks reliably, a month if you are lucky, but I never complain about this brevity. In fact, there are two glossy cuttings waiting in my holding area for somewhere to release them into grass. I’d like to see how ‘Cooper’s Burmese’ would take to not having anywhere to climb. I have a hunch it might mound and then stop its advance with nowhere to go, so in long grass on a bank I could simply edit its longest limbs from a sensible distance with long-armed pruners.

Rosa glauca

Rosa glauca

We have removed all the double David Austin roses from the garden and made a cutting area where they sit in sensible rows with dahlias and cutting peonies. Their opulence is wonderful in a vase, but not where I want things to feel on the wild side. Instead, Rosa glauca has made its way into the perennial planting, Its young coppery foliage ages to a completely matt grey-green as June gives way to full summer and it makes a delectable background, arching elegantly and scattering tiny, perfectly formed, pink dog roses along its limbs, which become mahogany-dark hips in autumn. I love it and am pleased to have it back after not having the room when gardening in London. If left untouched it will form a loose bumound of six foot in all directions. However, it can be coppiced hard every third or fourth year for the benefit of new, strongly coloured foliage, although you will have to wait a year before it starts to flower again.

Rosa ‘Scharlachglut’

Rosa ‘Scharlachglut’

The last time I grew Rosa ‘Scharlachglut’ was at Home Farm, where it spilled through the gold-flowered oat grass, Stipa gigantea, in the Barn Garden. Cultivated roses and grasses make curious bedfellows in the borders, but the singles sit well with informality. The colour in the enclosed space of the Barn Garden was deliberately provocative and you could feel the race of your pulse when the reds and pinks came together. ‘Scharlachglut’ means ‘Scarlet Blaze’ (it is sometimes sold as ‘Scarlet Fire’) and, true to its name, it flames fiercely against the green in the landscape here, but I am delighted to see it unapologetically announcing summer.

Though once blooming – as are its companions above – its brevity is remarkable. Scarlet, perfectly shaped buds open bright vermilion and age to a hot, cerise pink so that a range of colour appears along the length of arching limbs. As the flowers age they also increase in size and, although perfume is not its greatest strength, no matter, its presence is astonishing. Though I currently have it growing through comfrey and inula for later, as the planting matures I will add cow parsley so that the scarlet is suspended in cooling white. The timing is at the point of crossover where the lace of the anthriscus is dimming. When the cow parsley is over they will both be gone.

Rosa x odorata ‘Bengal Crimson’

Rosa x odorata ‘Bengal Crimson’

Up by the house, and the only recurrent rose in this collection, is Rosa x odorata ‘Bengal Crimson’. Once again, this is a cutting from the garden in Peckham, where my original plant will be presenting less of a problem to its owners. Rosie Atkins gave me the mother plant when she was the curator at The Chelsea Physic Garden. It grows there in several places, spilling informally from the borders, for it is almost impossible to prune. The growth is soft and thornless, the limbs reaching whichever way they choose to go, but forming something lovely despite the lax behaviour. Being slightly tender, it loves London living and will easily grow to two metres or more in each direction against a wall, or taller with support in a sheltered position.

It hated life here initially and my young cutting burned and frazzled where it was exposed in its windy holding position. I have now found it a sheltered corner in the lea of the house where it looks like it ought to. Soft and choice, with pale, apple-green foliage and flowers that refuse to conform to order. Opening from perfect buds of crimson intensity, the single flowers rarely open completely, but fold and roll informally, fading so that they too have variance when they come together. As they do, one after another without pausing, until winter curtails the willingness to throw out more growth. That said, it is often in flower at Christmas, although by then the flowers are chilled to a softer pink. With a plant that is always so giving, it is important to repay it with the care of deadheading by taking the spent sprays back to fresh new growth. In doing so, you can give it just the amount of attention it needs to keep the plant looking good and, after a brief pause, it will respond with more flower. A simple exchange, and an opportunity to spend some time up close with this beauty.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 9 June 2018

I have recently returned from the opening of one of my biggest projects to date and feel the need to tell the story, as it is remarkable for its scale and farsightedness. Mr. Ma, our client and the visionary behind the forty-five acre development, started the journey over fifteen years ago. A dam was about to be built near his hometown in Jiangxi province south-west of Shanghai, and with its construction came the loss of the valley’s ancient camphor trees and Ming and Qing dynasty settlements of merchants’ houses. By the time I came into the story, and indeed it was the reason that I did, Mr. Ma had moved over ten thousand camphor trees to their new home in Shanghai.

Their journey was an extraordinary one. Some are believed to be almost two thousand years old and were so big that they had to be transported the 600 kilometres on army tanks. Bridges had to be made to get them across rivers, and tunnels excavated so that the cargo could pass. The trees were planted in a nursery on the outskirts of Shanghai, very close to a site which Mr. Ma had secured for a new development. Here a series of old warehouses were also repurposed for storage of the merchants’ houses which had been dismantled brick by brick and painstakingly repaired from the damage they had sustained during the Cultural Revolution.

Mr. Ma with some of the rescued and replanted camphor trees

Mr. Ma with some of the rescued and replanted camphor trees

A warehouse containing some of the dismantled Ming and Qing dynasty merchant’s houses

A warehouse containing some of the dismantled Ming and Qing dynasty merchant’s houses

A detail of the stone carving on one of the antique villas

A detail of the stone carving on one of the antique villas

I was introduced to Mr. Ma in 2012 by his friend and collaborator Han Feng, who had been tasked with helping to find a landscape designer to design the grounds. Han Feng and I had met at the Design Indaba in Cape Town earlier that year, where we had both been invited to speak and we met in London to talk about the project. I was inspired by the story of the rescued camphors and the idea of making them a new home, so we agreed to meet Mr. Ma when I was next in Japan at the Millennium Forest so that he could see my work there.

By this point Aman Resorts were collaborating with Mr. Ma to make a hotel and associated grounds and Kerry Hill Architects had worked up a masterplan for the site. Once I was on board we were tasked with detailing the whole site from the hotel to the streetscapes and a series of garden blueprints that would be used to furnish the gardens of 44 private villas; 26 antique merchant’s houses and 18 contemporary interpretations of them.

Mr. Ma was busily working away in the background with the government to secure a site of double the size that would become the backdrop to the development and allow the green lung of the camphor forest to reach out and take on this new ground. We were also tasked with designing the masterplan for the park, repurposing one of the agricultural canals to form a dividing lake and masterminding a wetland of considerable scale that would allow us to recycle and purify all the water that would be needed for the water features on the site. It was an extraordinary opportunity to create a public park that would also act as an environment to include wetland walks, meadows and a considerable acreage of woodland. A green heart for a new city that was quickly sweeping up and around the site, as the agricultural land was repurposed for the urban sprawl.

The site masterplan with Amanyangyun in the north and east and the forest park to the south west

Once it was complete we passed the park masterplan on to a local firm of landscape architects and concentrated our energies on the Amanyangyun site. However, it is gratifying now to know that the first phase – the lake, the wetland and the woodland that links the two sites – is already in place. In China things happen at an alarming pace and at a scale that we are unaccustomed to here, so in many ways it was good to pull back at this stage after securing the big ideas and concentrate on the detail of Mr. Ma’s site.

It took two years of careful collaboration with the architects, who were a delight to work with, clear in their thinking and open to the contrast of an informal overlay on the rigorous grid that defined their masterplan. My own journey, and that of the team that works with me in the studio, was put on a very steep learning curve. We had to learn fast about the very different cultures and way of doing things and we couldn’t have done that without the trust and thoughtfulness of our client who had put a team in place that helped to translate our ideas.

We were taken to see traditional Chinese gardens to understand their ethos, aesthetics and cultural importance. They were completely new to me, the precursor to the Japanese gardens which I have come to know well from my time spent there, but entirely different in their aesthetic. I was keen not to emulate the Chinese garden at the villas on the site, but it was important to understand the culture and how we could create something naturalistic that would sit comfortably in Shanghai and not feel out of place.

One of the camphor-lined streets during construction in 2016

One of the camphor-lined streets during construction in 2016

The same view this year

The same view this year

The king camphor tree at the heart of the construction site has a red ribbon tied round it

The king camphor tree at the heart of the construction site has a red ribbon tied round it

A different view of the same area after completion

A different view of the same area after completion

Mr. Ma and the king camphor tree at the opening ceremony in April

Mr. Ma and the king camphor tree at the opening ceremony in April

We soon found that, despite the vast range of Chinese plants that we grow and depend upon in the west, our choices on site were very limited. The Chinese garden depends upon a tiny palette compared to a western garden and thus the nursery trade there is very limited. Bamboos, from ground covering forms to timber bamboos, were not in short supply, neither were Nandina and Osmanthus, but our tree palette was narrow, with only two magnolias to choose from, M. grandiflora and the beautiful M. denudata. We had flowering Malus and plums, camellias and a number of auspicious fruits that we used close to the buildings. And there was no shortage of Chimonanthus so the building blocks were enough. It was what we did with them that made the difference.

Modern landscape design in China sees the groundcover layer packed densely with blocks of low level shrubs, such as azalea and Fatsia, but I wanted breathing space between a multi-stemmed layer of flowering trees that would sit under the canopy of the camphors and keep the space at human level feeling airy and light. We designed a number of groundcover mixes that mingled the staples together informally. Ophiopogon and Liatris sweeping through in a gently shifting constant with runs of Aspidistra in the deepest shade, which was replaced by the likes of Iris sibirica and Chasmanthium latifolium out in the glades, where we had made room for the light to break the overarching canopy.

Overview of the villa complex

Overview of the villa complex

Entrance garden of an antique villa the first spring after planting

Entrance garden of an antique villa the first spring after planting

Entrance walkway iris planting

Entrance walkway iris planting

Rear private pool garden of an antique villa

Rear private pool garden of an antique villa

We used a palette of Chinese natives and local wetland species to encourage wildlife, but pumped up the volume amongst the restful sweeps of green with lotus ponds that sat close to the buildings, coloured Nymphaea in water bowls on the terraces and highly scented Gardenias by doorways. The climate, though temperate, is just that bit warmer than London so we were able to include bananas in sheltered corners and Trachycarpus for the grandeur of architectural foliage.

After my initial dismay at the apparent limitations of choice, our palette soon felt big enough to do something interesting, but I did choose to import Hydrangea serrata from Japan, as we only had access to hortensia and H. quercifolia. By including the H. serrata we were able to ring the changes and make the development singular. Pink, white and ‘Macrobotrys’ Wisteria floribunda were also imported as we only had access to Wisteria sinensis, which is the shorter-flowered of the two species. These additions to the staples and the commitment to breathing spaces in the planting soon made the difference.

The main riverside entrance

The main riverside entrance

The hotel entrance

The hotel entrance

We honoured the Chinese traditions with an auspicious fruit tree by every door and trees and shrubs that represented welcome or well-being and were well known for this layer of storytelling in the landscape. Our plans were all vetted by a feng shui master before anything was built – and we had to make some changes, but most of the moves in geomancy are based on good common sense and the changes were few. I suspect we were lucky.

There are numerous tales to tell about how we got to the point that the hotel and the grounds of the first villas were finally opened this spring, but they finally are and behind the scenes work continues to complete the remaining parts of the site. Though the planting has been in a year at most, it is already beginning to pull the buildings together. You look up to see the camphor trees regenerating, the King tree in the main courtyard already assuming presence. It will be a time before their branches reach to touch and cast shade, but it is good to have been part of helping them to do so.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photos: Dan Pearson and Sean Zhu

Published 2 June 2018

A year ago now, and with the prospect of planting up the final part of the garden in the autumn, I wanted to add some variety to the range of plants that was available from my favourite nurseries. So, I set about sowing some additions from seed, to feel that I’d grown them from the very beginning and to understand them fully. Bupleurum perfoliatum and Aquilegia longissima were needed in quantity to weave into the new planting and to jump around, as if self-sown. It was also good to revisit plants that have become hard to obtain, such as Aconitum vulparia, a creamy wolfbane from Russia which I’d grown as a teenager and had a hankering for again.

The success stories of the plants I knew and understood were reassuring. Those that I didn’t, vexing but fascinating nevertheless. It is a mistake to throw out a pot of seed that hasn’t germinated within a year, because it may simply be waiting for its moment. The Viola odorata ‘Sulphurea’ needed the freeze of a winter to break dormancy and I learned by chance that Agastache nepetoides needs light to germinate, and so should be surface sown. My usual top dressing of horticultural grit, used to prevent moss and as a slug repellent, was washed from the sides of a pot by a leaky rose, opening up a window of opportunity, the seed germinating there and there only to burn this fact into my memory. Some seed may have been too old by the time it was sown, with very poor germination on the Anemone rivularis, but the small numbers mean that the plants that made it are that much more precious. Although the value of seed-raised plants increases when you have tended them from their vulnerable beginnings, it is also good to feel that you can be generous, because some plants are just so easy.

Having grown the biennial Lunaria annua ‘Chedglow’ the year before, the first plants had all flowered and seeded so an interim generation was needed to set up a continuity. The large, flat seed threw out fat cotyledons in a matter of days and the distinctive purple-tinged foliage was already there in the first true leaves. Where the perennial Anemone rivularis took their time to build up strength for the life ahead of them and had to be watched because they were so slow, the pioneering nature of the Lunaria means that you have to keep up to make the most of the growing season. The seedlings were potted on into 9cm pots as soon as the first true leaf was properly formed, handling the seedlings only by their cotyledons and never their vulnerable stems. With the new opportunity of their own space, they worked up a rosette last summer that was hearty enough to plant in the autumn and bolt the early spring of flower a year after sowing.

Hesperis matronalis var. albiflora with Paeonia delavayi

Hesperis matronalis var. albiflora with Paeonia delavayi

Of the short-lived perennials I’ve used to provide for me early on in the life of the establishing garden, the Hesperis matronalis var. albiflora have been good to revisit. The white sweet rocket was a plant of my childhood garden, where it had sprung from the clearances of brambles like a phoenix from the ashes. Rising up fast with the cow parsley and easily as tall, its early flower bridges late spring and early summer. I have not had room to grow it for a while, because its ephemeral nature this early in the season can easily smother neighbours, to leave a summer gap when you cut it back to the rosette once it’s done. Let it seed and you will find a rash of youngsters, for it is also a pioneer that sees seedlings bulking up over summer in readiness to conquer new ground the following spring. This eagerness can easily be tapped, and it is good to leave a couple of limbs to go to seed as the plants are only good for two or three years before they exhaust themselves.

Sweet Rocket are adaptable to both an open position or to dappled shade, but the advantage of a cool position is that they grow less vigorously and take less ground. Mine were interspersed randomly in the planting to perfume the steps that descend to the studio and their distinctive, sweet scent is held in the stiller air caught behind the building. Bulking up fast once they were released from their pots, they have provided me with a rush of new life that has outstripped but complemented their slower growing neighbours. Seed-raised plants are more often variable and this is one of the joys of growing your own. Of the twenty or so plants, I must have almost as many different variants.

There is a blowsy head girl, brighter and showier than its neighbours and probably the one you would choose as a complement to a Chelsea rose garden, although she leans and topples under her own weight of flower. There is a perfectly behaved plant nearby. Just as white, but smaller and quieter and perfectly happy to stand upright without staking. This is probably the one that you would propagate from spring cuttings if you wanted something showy and reliable. My favourites have a wilder feel though; a grey-pink cast to some and more open flower panicles to others that provides the space I am so keen on and a lightness in the planting that feels less dominant. Head Girl has been used for cutting and will come out when I cut the plants down to prevent it from seeding and allow my slower-growing perennials around them the room they need to fill out later in the summer. Though the Actaea, the Zizia and the peonies are destined to provide a more certain future, the fast sweet rocket will always be just that.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photos: Huw Morgan

Published 26 May 2018

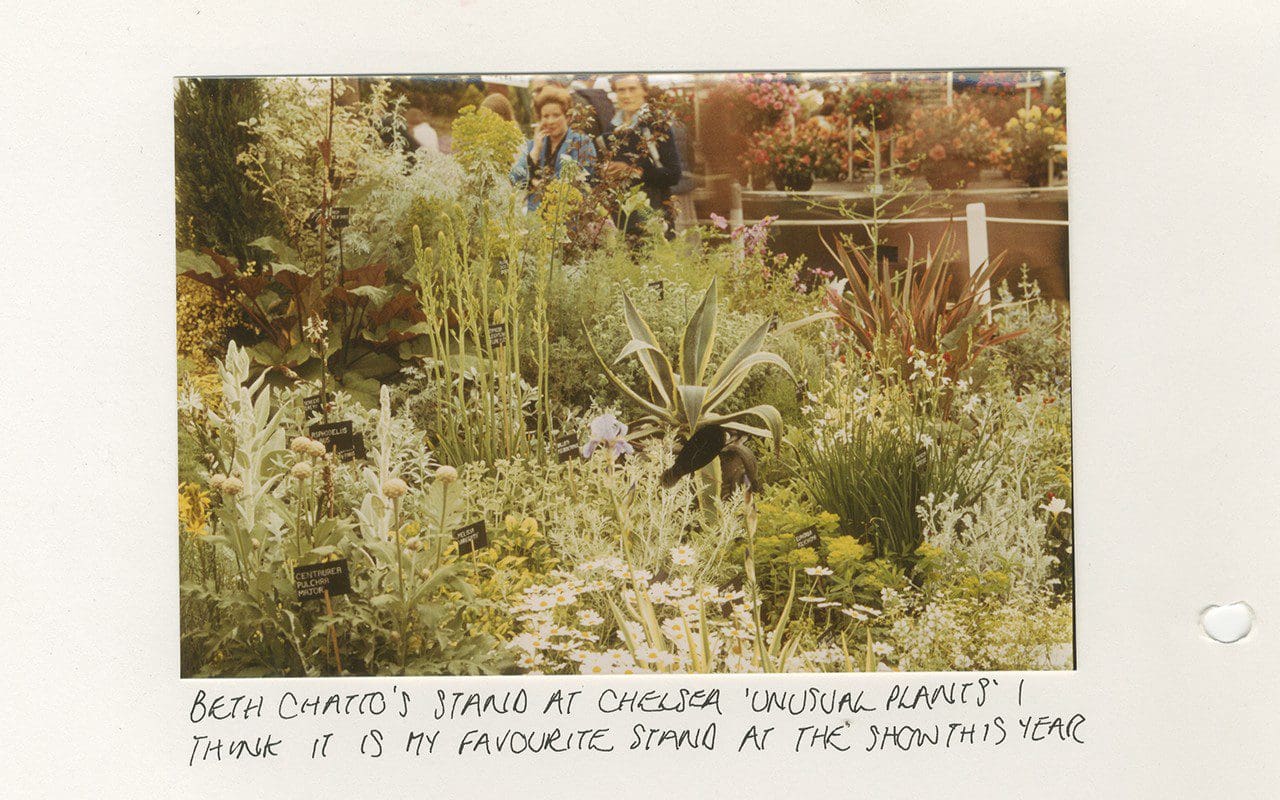

I first encountered Beth Chatto in 1977 at The Chelsea Flower Show. It was the first time she had exhibited and, aged 13, it was also the first time I’d attended the show. I remember quite distinctly the spell that was cast when my father and I came upon her stand. The froth, confection and sheer horticultural bravado that made the show remarkable fell into the background, and suddenly everything was quietened as we stood there, entranced.

We worked the four sides of the display, noting the differences between the plants that were grouped according to their cultural requirements. Leafy woodlanders cooled the mood where they were mingled together, with barely a flower, in celebration of a green tapestry. Nearby, and separated by plants that allowed the horticultural transition, were the delicate blooms of the Cotswold verbascums, ascending through molinias and sun-loving salvias. Plants with none of the pomp of the neighbouring soaring delphiniums, but which were captivating for their modesty and feeling of rightness in combination. The exhibit stood apart and was confidently delicate. We learned from it, filling notebooks hungrily with sensible combinations, happy in the knowledge that the wild aesthetic we were drawn to was something attainable.

A page from Dan’s 1980 Wisley notebook

A page from Dan’s 1980 Wisley notebook

At that point no one else was doing what Beth was doing and, when I met Frances Mossman, who commissioned me to make my first garden five years later, it was those show stands that brought us together. We talked at length about Beth’s ethos, the excitement of combing her catalogues of beautifully penned descriptions and our resulting purchases.

Of Crambe maritima, she wrote, “Adds style and grandeur to the filigree grey and silver plants. Waving, sea-blue and waxen, the leaves alone can dominate the border edge, while the short stout stems carry generous heads of creamy-white flowers in early summer. The stems are delicious, blanched in early spring, served as a vegetable. 61 cm.”

While Gladiolus papilio is, “Strangely seductive in late summer and autumn. Above narrow, grey-green blade-shaped leaves stand tall stems carrying downcast heads. The slender buds and backs of petals are bruise-shades of green, cream and slate-purple. Inside creamy hearts shelter blue anthers while the lower lip petal is feathered and marked with an ‘eye’ in purple and greenish-yellow, like the wing of a butterfly. It increases freely. Needs warm well-drained soil. 91 cm.”

Crambe maritima with Verbascum phoenicium ‘Violetta’, Cirsium rivulare ‘Trevor’s Blue Wonder’ and Matthiola perenne ‘Alba’ in the gravel by the barns

Crambe maritima with Verbascum phoenicium ‘Violetta’, Cirsium rivulare ‘Trevor’s Blue Wonder’ and Matthiola perenne ‘Alba’ in the gravel by the barns

Crambe maritima

Crambe maritima

We came to rely upon her nursery of then ‘unusual plants’; me with a long border I had planted in my parents’ garden, and Frances with her own first garden in Putney. Unusual Plants was the place we would go to help us make that first garden together and, when we started making the garden at Home Farm in 1987, it was Frances who wrote to Beth to tell her of her positive influence and of what we were doing there to make a garden without boundaries. Beth wrote back with careful responses and encouragement. Once I had got over my shyness, I too started to write and we struck up a friendship from which I will always draw inspiration and refer back to as pivotal in my own development.

Beth made an indelible impression with her words, wisdom and practical application of good horticulture. In this country she was arguably the link back to the beginnings of William Robinson’s naturalistic movement and an informality that drew inspiration from nature. Her writings were always dependable and combined the artistry of an accomplished planting designer with the fundamental practicality of someone who had seen how plants grew in the wild and knew how to grow them to best effect in combination in a garden.

The gravel garden at Home Farm in 1998. Planting included Verbascum chaixii ‘Album’, Nectaroscordum siculum, Glaucium flavum var. aurantiacum, Stipa tenuissima, Limonium platyphyllum and Eryngium giganteum, all from Beth Chatto Nursery. Photo: Nicola Browne

The gravel garden at Home Farm in 1998. Planting included Verbascum chaixii ‘Album’, Nectaroscordum siculum, Glaucium flavum var. aurantiacum, Stipa tenuissima, Limonium platyphyllum and Eryngium giganteum, all from Beth Chatto Nursery. Photo: Nicola Browne

If you study Chelsea today, it is easy to overlook the influence she had on the industry of nurserymen and designers. The ‘unusual plants’ that were her palette are no longer so, and the way in which they were combined naturalistically on her stands has become the status quo. Rare now are the perfect bolts of upright lupins and highly-bred, colourful perennials, not so the mingled informality of plants that are closely allied to the native species, many of which had their origins at her nursery.

Though we will all miss her presence after her sad departure last weekend, her influence will remain strong. In the hands of Beth’s trusted team, led by Garden and Nursery Director, Dave Ward and Head Gardener, Åsa Gregers-Warg, the gardens and nursery have never been better. In recent years, as Beth’s health has deteriorated, Julia Boulton, her granddaughter, has firmly taken the reins and, as well as ensuring that the gardens and nursery continue into the future, has been responsible for setting up the Beth Chatto Education Trust and, this year, a naturalistic planting symposium in her name which takes place in August. At its heart the gardens will become a teaching centre, a living illustration of Beth’s passion for plants and her ecological approach to gardening.

‘Beth’s Poppy’ – Papaver dubium ssp. lecoquii var. albiflorum

‘Beth’s Poppy’ – Papaver dubium ssp. lecoquii var. albiflorum

Looking around my garden this morning, I can see Beth’s influence almost everywhere in the plants that are grouped according to their cultural requirements. Be it the ‘pioneers’ in the ditch, which have to battle with the natives, or the colonies of self-seeders I’ve set loose in the rubble by the barns, her teachings and plant choices are everywhere. Her plants also connect me to a wider gardening fraternity, a reminder of her generosity and willingness to share. The Papaver dubium ssp. lecoquii var. albiflorum that has seeded itself around the vegetable garden was first given to me by Fergus Garrett as ‘Beth’s Poppy’, since she had passed on the seed, while the Ferula tingitana ‘Cedric Morris’ growing against the breezeblock wall by our barns, was collected by her great friend, the artist and aesthete, who helped open her eyes to the beauty of plants.

Ferula tingitana ‘Cedric Morris’

Ferula tingitana ‘Cedric Morris’

Paeonia emodii ‘Late Windflower’

Paeonia emodii ‘Late Windflower’

A visit to the nursery is still one of my favourite outings. I can guarantee quality and know that I will find something that I have just seen growing right there in the garden and have yet to try for myself. About twelve years ago, on a trip that culminated in a full notebook and an equally full trolley, Beth gave me a plant of Paeonia emodii ‘Late Windflower’ accompanied with the usual words of good advice about its cultivation. Sure enough, it is a good plant both in its ability to perform and in terms of its elegance. I moved it carefully from the garden in Peckham and divided it the autumn before last to step out in an informal grouping in the new garden. Last Sunday, although I did not know that this was the day she would finally leave us, the first flower of the season opened. As is the way with a plant that has a heritage, I spent a little time with her, pondering aesthetics and practicalities. I know for certain that it will not be my last conversation with Beth.

Beth Chatto 27 June 1923 – 13 May 2018

27 June 1923 – 13 May 2018

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 19 May 2018

In March, the week after my mum died, we received an email from Simon Bray, a Manchester-based photographer and artist, asking if we might be interested in featuring him and a new book he was self-publishing. The book, Signs of Spring, is a collection of family photographs he has assembled of his childhood garden, which was initiated in part by the death of his father, and the importance the garden had in Simon’s memories of him. Although it was pure coincidence that Simon chose to write that week, it felt as though I was being offered an opportunity to remember mum in a new way. The more of Simon’s work I saw, the stronger this feeling became.

Simon, can you tell us how you came to study and work with photography ?

I began taking photographs when I moved to Manchester from Winchester for university. It was quite a shift for me, having lived in rural Hampshire my whole life, so I would walk everywhere, exploring the city by foot. Taking pictures helped me assimilate. I’ve never actually studied photography. I studied music, but as a drummer, so taking photos was something I could do on my own without requiring others and the practicalities that come with playing drums! Photography became one of many ways in which I like to express myself creatively and I’m now very fortunate to call it my job, making time for both artistic projects and commercial work.

You have a clear interest in place as a locus for memory. How did you come to realise and key in to this aspect of photography ? Has the idea of loss always been intrinsic to your work, or is it something that has developed over time ?

The notion of place has always been central to my practice. As I mentioned, Manchester was a starting point, but photographing places such as The Lake District helped me to understand that there was something about taking photographs in certain locations that excited me and made it easier to express myself. This has led me to explore my own connections to physical places and also work with others to explore theirs. It’s not always somewhere grand and romantic like the lakes, the garden from my family home has probably been the most significant place in my life and where I took many photographs.

The notion of loss came into my work after my dad passed away in December 2009. It took me quite a while to pick up my camera after that, nothing seemed significant enough to make pictures of but, over time, I began to appreciate that my photography could actually be hugely beneficial in helping me to express how I was feeling.

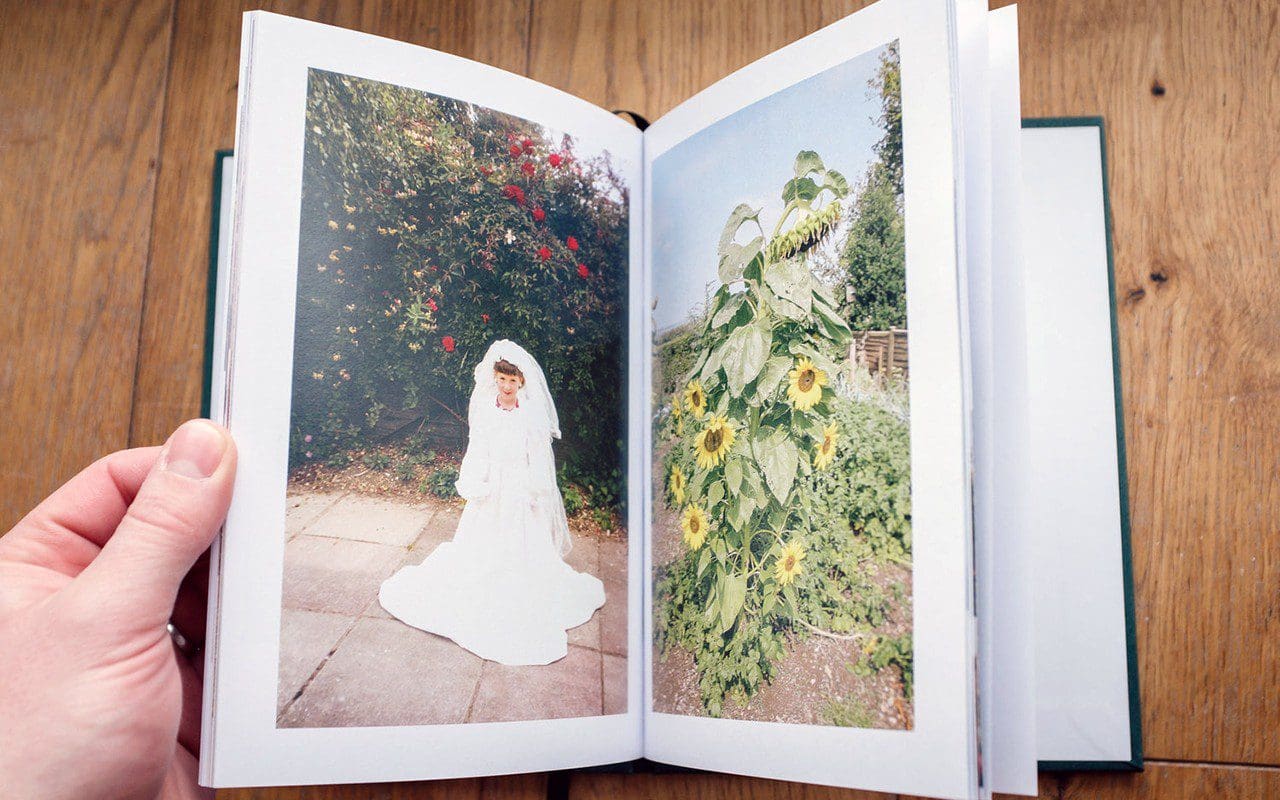

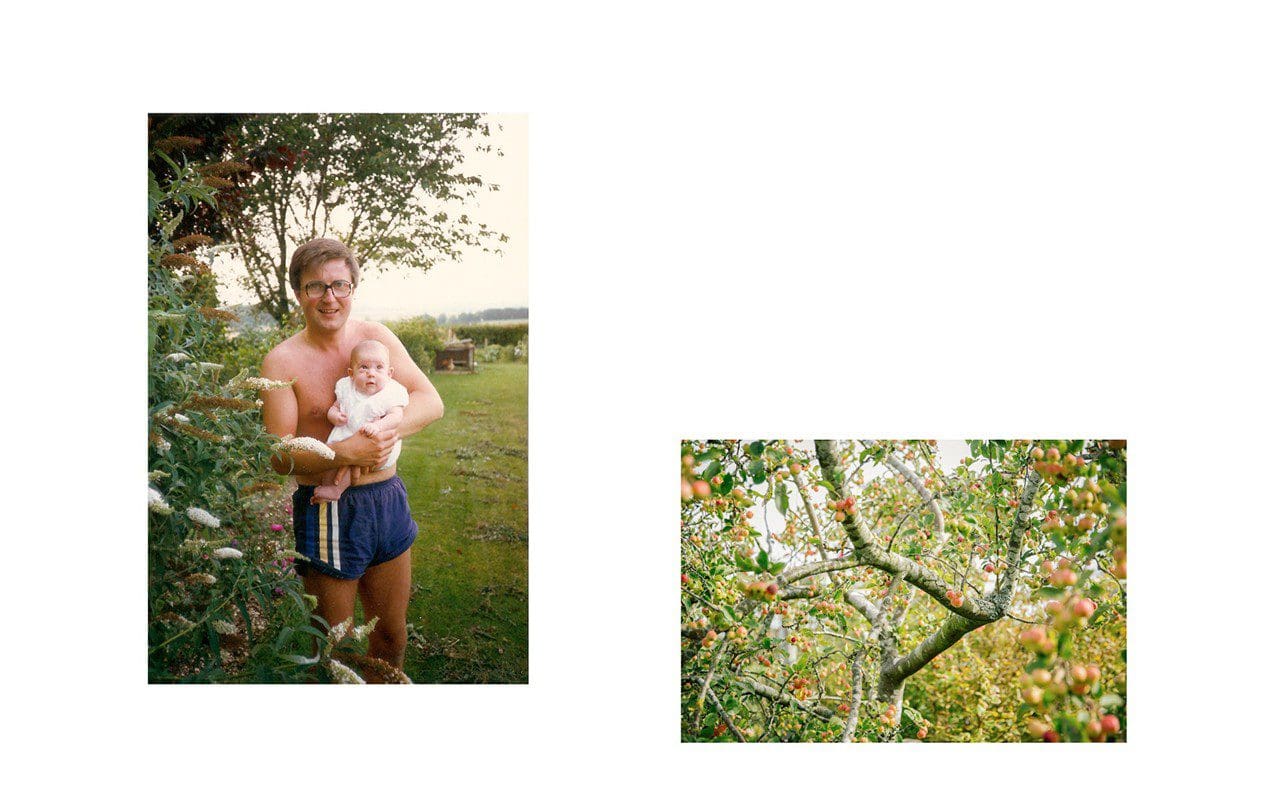

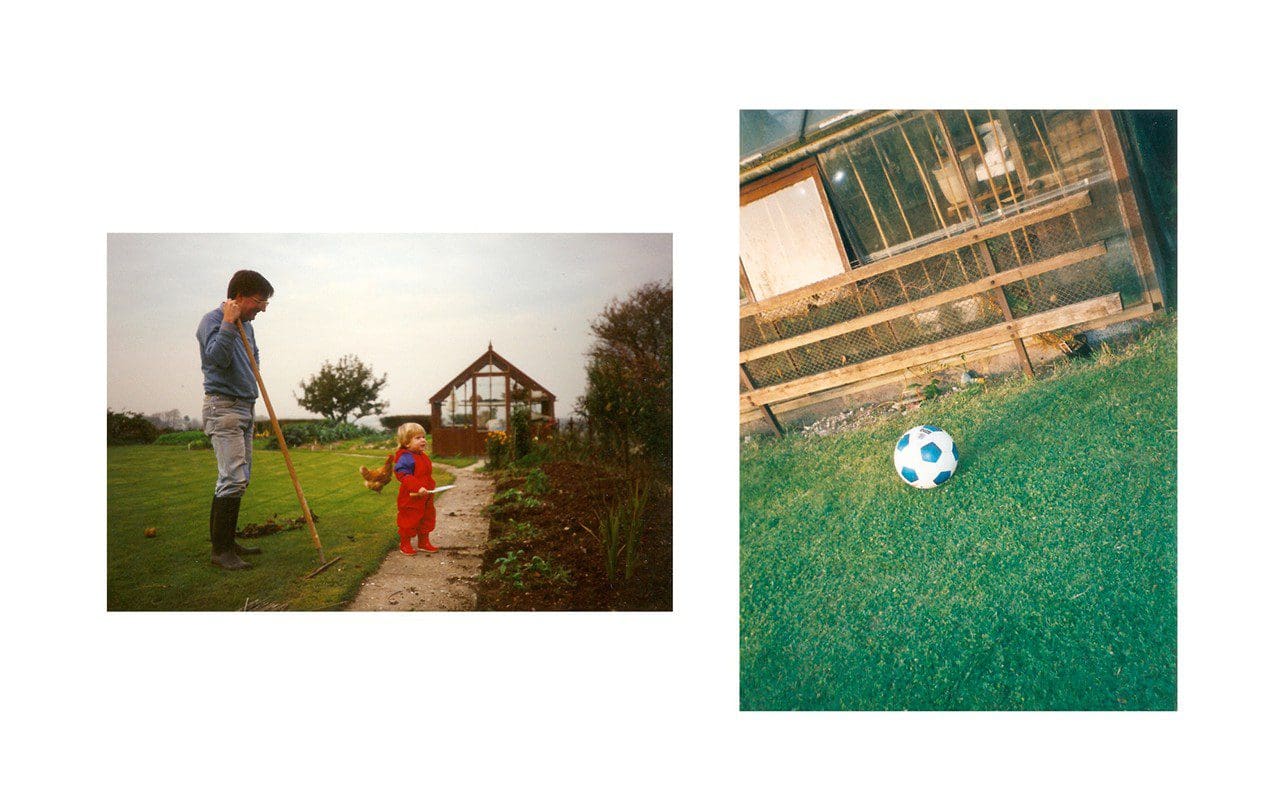

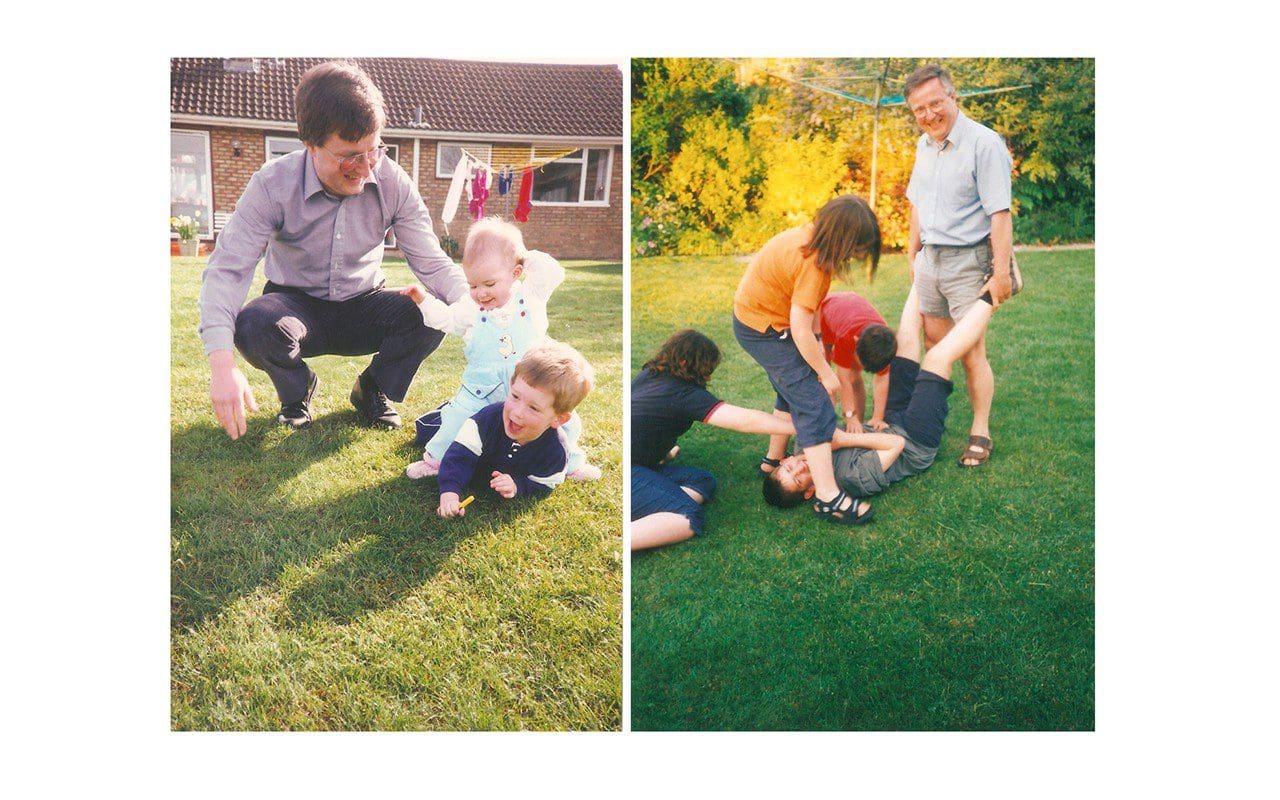

Spreads from Signs of Spring

Spreads from Signs of Spring

I was really moved by Signs of Spring, the book you have published in memory of your dad. Also your ongoing photography project 30th December which is also connected to memories of your father. Can you tell me how each of these projects came about, what they mean to you and what they provide for you ?

Both of those projects are about place, memory and loss, manifested in different ways. Signs of Spring is a collection of photographs that I’ve gathered together, found in family photo albums. It’s not a memorial as such, more a celebration of the life of our family in the garden where I grew up. Dad was a very keen gardener, having grown up on a farm in Cornwall he spent every hour of a daylight outside, producing vegetables and fruit and keeping everything very well maintained. It was a playground for my sister and I and the location for countless family occasions, so it holds many special memories for me. After dad passed away, mum vowed to keep the garden going, which she did very well, continuing to produce fruit and veg, but a couple of years ago she decided it was time for a fresh start and moved down to Penzance. That meant having to say goodbye to the house and garden I’d grown up in, which was far harder than I’d imagined. It felt like having to let go of Dad all over again, so I wanted to celebrate the garden by producing this book.

The 30th December project is very similar actually. It’s the anniversary of dad’s passing and, once I’d picked up my camera again, on each anniversary I’d go out and make pictures. Last year I made a series of handmade books with photographs taken at dawn on St. Catherine’s Hill in Winchester, somewhere we used to go as a family. The pictures aren’t necessarily about loss, they’re not inherently sad pictures, but it’s a process that helps me remember and engage with how I’m feeling on that day. I shall keep on making photographs on 30th December each year, wherever I am in the world.

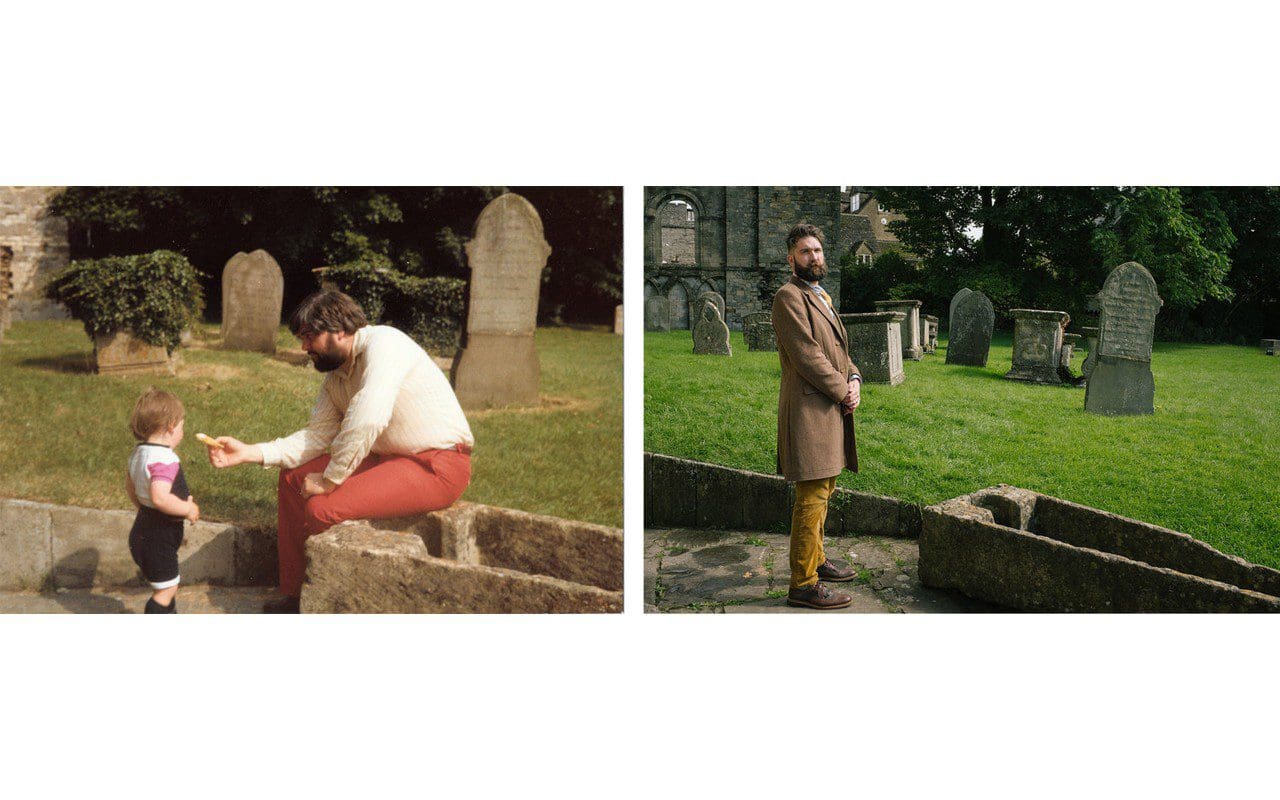

Photographs from 30th December

Photographs from 30th December

I am interested in how you see gardens as a receptacle for childhood and family memories. Can you tell us your thoughts about this and how gardens differ from other landscapes, both urban or rural ?

Unless you’re a farmer, your garden is a patch of the world that you’ve been gifted to take care of. You can do with it as you please, you can pave it over and not have to think about it, or you can cultivate it to feed your family, create a place to relax and share with others, or fill it with flowers for others to see and enjoy. There’s something very satisfying about a well-maintained front garden! It’s the sense of ownership and responsibility that makes it differ from urban and rural spaces, not that you can’t feel ownership of the town you live in or your favourite national park, but those are shared spaces, your approach differs to that of your own garden. I’ve recently moved to my first house that has a garden and I’m getting so much pleasure from looking after it. Simply just staring out the window at the birds feeding as I write this is making me feel relaxed!

Spreads from Signs of Spring

Spreads from Signs of Spring

The Loved&Lost project looks at a wide variety of places through the prism of loss, memory and the passing of time. I found it very cathartic reading about other people’s experience of losing a loved one. Can you tell me more about how the project came about and what you learnt from it ?

As I alluded to earlier, after the loss of my father I found ways to try and help others engage with their loss, and this now manifests itself as the Loved&Lost project. I invite participants to find a family photograph of themselves with somebody who is no longer with us, we then return to the location of the photograph to re-stage it and record a conversation about the day. It’s amazing how impacting it is to return to the physical location of the photograph. It brings back so many memories and makes it all very tangible for the participant. I want to encourage them to engage with their loss in a different way. The photograph is simply a starting point, but the process allows us to have a conversation, to recall the day the first image was taken, to share their account of losing someone close to them, but also celebrate the person who is no longer here.

When dad passed away, lots of people asked me how I was, which is a very kind and natural thing to do, but in the mix of it all, I didn’t actually know the answer to the question and so I didn’t really want to talk about me, what I wanted to talk about was dad. I found myself in social situations recalling memories, jokes, anecdotes that he would have enjoyed, but not really being able to share them because there was no context for everyone else, so I wanted to create a forum in which it’s absolutely fine to share your favourite stories about that person that no-one else knew quite like you did.

The project is ongoing, and I learn something new from every person I meet. It’s not about having to be strong or getting over it after a certain amount of time – some people take part months after their loss, others many many years – the loss is still there, but how you engage with it varies. Lots of people end up restructuring their lives after a significant loss, your focus changes and priorities get realigned, it shapes you, not always in ways that you understand in the moment, but over time I find that most people feel it’s important to know that some good has come out of their pain, and for me, I’d like to think that Loved&Lost is that.

Double portraits of Paul, Emelie and Will from Loved&Lost

Double portraits of Paul, Emelie and Will from Loved&Lost

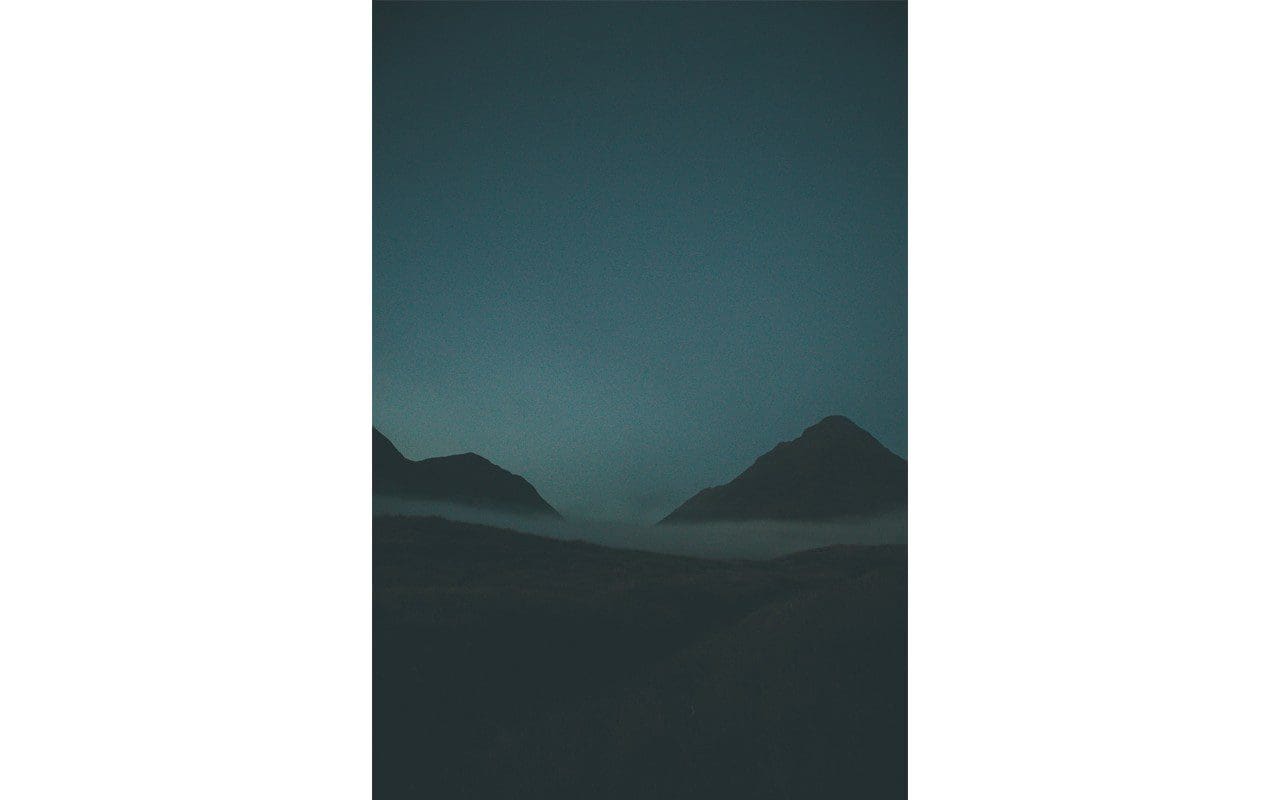

Much of your landscape photography has a very particular atmosphere of emptiness or vacancy, like stage sets where the protagonist has just left or is just about to arrive. Can you explain your feelings about ‘wild’ landscapes and how we relate to and inhabit these environments ?

I really like that analogy, because as much as the landscapes within the UK especially can be wild, most of them are fairly approachable as well. Obviously you need to be cautious and equipped according to the weather, but there are so many accessible and varied locations within these British Isles that can be truly breathtaking. So many of us use the outdoors as a means of escape. I will always feel better about life if I’ve spent the day outside, particularly in some mountains or by water, so it feels very natural to be drawn towards that as subject matter photographically. I quite intentionally don’t include people within my landscape photographs. In fact, sometimes there’s not much of anything in my work, probably just sky and mist with a bit of land at the bottom of the frame! I think that’s a result of my yearning for space. My mind seems to be full of thoughts and ideas all the time and stretching my legs and exploring somewhere new seems to not necessarily turn that off, but brings clarity and energises me mentally. The space required for that comes through in my images, which sometimes can appear bleak or vacant, but I suppose it’s a thoughtfulness or consideration that gets subconsciously built into the photographs.

Photographs from Simon’s ongoing Landscape series

Photographs from Simon’s ongoing Landscape series

How did the The Edges of These Isles project come about and how did you collaborate with artist Tom Musgrove on it ?

Working with Tom came about after we did the Three Peaks Challenge together with a couple of friends. We established that we’d both like to be making more work inspired by landscape and that it would be very interesting to see how a painter and a photographer might be able to collaborate. It took us a couple of years, but we ventured all across the UK together, making work, sharing thoughts, ideas, music and establishing where our approaches to making work could meet and where they differed. We ended up making a 120 page book, a 25 minute film and have exhibited the work 3 times. It was a huge step forward in terms of my appreciation of what it means to be an artist and how I can engage with the subject matter before me and utilise it to express myself. The work I made on those trips is still some of my favourite that I’ve created. I’m a romantic at heart, so the aesthetic and notion of the sublime are very much in my mind when I’m working within the landscape, but I also want to bring myself into the image. I like to do my best to avoid making pictures that I know have been captured countless times before by awakening my senses in that moment to really understand how I’m going to make that picture, which is something I learnt from Tom.

What can you tell me about your involvement with One Of Two Stories, Or Both (Field Bagatelles), the piece by Samson Young that was commissioned for the 2017 Manchester International Festival ?

I was fortunate to be selected as one of six artists to take part in a fellowship with Manchester International Festival last year. This involved being placed within one of the festival commissions and I was very lucky to work with Samson Young, who had just represented Hong Kong at the Venice Biennale. It was incredible to see him at work, creating a 5 part radio play complete with live musicians, voice actors and foley artists, as well as constructing an installation for the Centre For Chinese Contemporary Art in Manchester. He invited me to play drums in the radio pieces and make a photograph for the installation, both of which were a huge privilege. I also got to engage with the other young artists and experience many other performances within the festival, which really broadened my horizons in terms of what I create and who my audience is. Not that I have the answers for those things yet, but it was a hugely inspiring experience.

Samson’s piece was all about the hypothetical journey of Chinese migrants to Europe at the start of the century travelling by train. It was amazing to observe how Samson created that world through the medium of radio, utilising the music, actors and created sounds. It formed amazing visual landscapes in my mind and really informed how I engaged with the characters in the piece. It got me thinking about how I construct the landscape images that I make, how much of it is me simply photographing what’s in front of me, and to what extent do I build the feel and atmosphere of an image in how I shoot and edit it.

Photographs from The Edges of These Isles

You are currently working with Martin Parr on a new commission for Manchester Art Gallery. Firstly, I’d love to hear your take on Martin’s photography and what it means to you. Then can you then tell me anything about the work you’re collaborating on?

Martin was one of the first photographers I was ever made aware of, and there’s something about his style which is so stark, but so honest at the same time and his sense of humour is something I know I’ve tried to seek out in my street photography work as well. I’ll see one of his images and know straight away that it’s his, which, as a photographer, is something I’ll always be aspiring to.

I began working with Martin in March as the producer for his commission with Manchester Art Gallery for an exhibition opening this November. The gallery is going to show a huge selection of Martin’s Manchester work from the past 40 years, from when he studied here in the early 70’s up until today, which is what we’re currently working on now. So I’m spending a lot of time arranging shoots, but then I get to work alongside Martin for a few days at a time and it’s a real privilege to observe him working, he’s so confident and assured, just being around him for a few days fills me with confidence.

And finally, what are you working on personally at the moment, and are there any opportunities for us to see your work anywhere ?

I have a couple of exhibitions coming up, the first is Duality, a documentary project that I’ve collaborated on with another Manchester photographer. Its focus is workwear and uniform, posing questions about how we perceive the individual based on their appearance, which they potentially haven’t chosen for themselves, but also how the individual perceives themselves based on what they’re wearing. That’s going to be on show at The Sharp Project, Manchester on 31st May.

I’m also showing a selection of stories from Loved&Lost at Oriel Colwyn in Colwyn Bay throughout July. It’s the first time the work will have been shown in a gallery, so I’m currently establishing how to do that sensitively and effectively.

Working with Martin and finishing off the Loved&Lost stories is keeping me fairly busy at the moment, but I have begun work on a couple of new projects, one inspired by the locations that feature in Brian Eno’s album Ambient 4 : On Land, and the other is about photographing smells, which I know is impossible, but I’ve just started developing the idea to see if it’ll work!

Interview: Huw Morgan / Photographs: Simon Bray

It is epimedium time again. Something that I always look forward to and am never disappointed by. I discovered my first buried under a bramble thicket in my childhood garden. I can see it now, a survivor of a garden that had been overwhelmed almost fifty years earlier. It was spring and we were clearing the remains of an old border and the soft, marbled foliage was at its most magical April moment. At that point I had never seen anything like it before, the delicate heart-shaped leaves, copper-toned and marbled red with veining. Hovering amongst them and emerging from fine, down-dusted buds were pale flowers. Aptly nicknamed Fairy Wings, they hovered under the tangle of thorns as if they had been waiting all that time to cast their spell on the ten year old me.

The plant in question was Epimedium x versicolor ‘Sulphureum’, which I use regularly now where something refined, but trustworthy is needed. They thrive in the inhospitable places created by the influence of deciduous trees and shrubs and are perfect for a cool, north facing position. The evergreen foliage forms a low mound of overlapping shields, amounting to no more than a foot in height and reliably creeping slowly sideways. Winter sees the foliage turn from dark green to bronze before it finally gives in as the new growth pushes through. Part the winter foliage at the beginning of March and you see the embryonic new growth already formed. At this point last year’s leaves can be sheared to the ground in established clumps to see the best of the new growth that soon comes to replace the old.

Epimedium x versicolor ‘Sulphureum’ foliage

Epimedium x versicolor ‘Sulphureum’ foliage

There are a number of good European epimediums and all those available make adaptable and foolproof groundcovers. The gold-flowered E. x perralchicum ‘Frohnleiten’, with its glossy foliage, is almost indestructible and the small-flowered E. pubigerum is a worthy plant too, with tiny creamy sprays of flower which I regularly include in planting plans. However, about fifteen years or so ago I started to discover the Chinese species, which had slowly been becoming available and since then I’ve been spoiled for good and forever.

The Chinese epimediums are more demanding than their easy European cousins. It would be foolhardy to think you could tuck them under the philadelphus and forget about them until their yearly cutback. They quickly let you know if the atmosphere is too dry, with shrivelling edges to their finely-formed leaves and they fail to put on growth if you don’t emulate the deep leaf-mouldy woodlands to which they are accustomed. I have tried, and then regretted, cutting their foliage back in March, and had to endure two years of sulking in return. But, for their exceptional beauty, they are worth the effort and, once you have cracked what they like and where they like to be, not quite as particular as you might think.

Epimedium davidii

Epimedium davidii

Epimedium ‘Spine-Tingler’

Epimedium ‘Spine-Tingler’

Epimedium ‘Spine-Tingler’ foliage

Epimedium ‘Spine-Tingler’ foliage

Epimedium franchetti ‘Brimstone Butterfly’

Epimedium franchetti ‘Brimstone Butterfly’

My little obsession started in the sheltered microclimate of the garden in Peckham. I grew them mostly in pots, which were kept in the still and shadow at the garden’s end. In April, after carefully picking over the damaged leaves, they were brought up to the house for us to marvel at their metamorphosis. The emerging leaves, flecked and chequered with bronze, ruby and purple, and the wiry stems pushing through in a reptilian reach, to throw a constellation of flower above them. Each of the species had something particular that set it apart from the others. The jagged foliage of E. fargesii looks almost aggressive, though it is not to the touch, whilst the darkly flecked foliage of E. myrianthum is like river washed pebbles in its roundedness.

I soon found that I had seedlings, which have proven to be highly variable. Specialist nurseries that have been hook-line-and-sinkered, have long lists of named varieties which reflects their willingness to cross. Though I am more selective now about how many seedlings I keep, I do have a particularly good one that looks like it has E. wushanense ‘Caramel’ in its genes, and possibly E. mebranaceum, with sprays well over two feet long, widely-spaced flowers an inch across and dramatically red-speckled foliage.

Peckham seedling

Peckham seedling

Peckham seedling foliage

Peckham seedling foliage

Epimedium ‘Stormcloud’

Epimedium ‘Stormcloud’

Epimedium ‘King Prawn’

Epimedium ‘King Prawn’

Epimedium fargesii ‘Pink Constellation’

Epimedium fargesii ‘Pink Constellation’

My conundrum – and my saving grace, for I would have fifty not two dozen by now if I had the conditions – is that I have just one sliver of suitable shelter here on our bright, windy hillside. The recess behind the house in the north shade is just wide enough for three zinc cattle troughs, which have been backfilled with a friable mix of good soil and compost. A wicked March wind from the north east will be their undoing if they have already started into growth, but they have done well for me now that they are out of pots and have reliable moisture at the root. We have three windows that look onto them from the ground floor and they are the stars of these little theatres for six to eight weeks in the spring.

As time goes on, I have found that some are better doers than others and that all the time nurserypeople are selecting improvements. Experience has shown that the straight species E. wushanense struggles here, while it did much better in the increased warmth of London. I have moved it back to be in the shade of the Katsura in the studio garden. However, the named offspring, E. w. ‘Caramel’ does splendidly and must have some more cold-tolerant tolerant blood in it from something hardier. E. fargesii ‘Pink Constellation’ has now been eclipsed in my opinion by a form called ‘Heavenly Purple’, which was bred by Karen Junker’s son, Torsten, and which I was lucky enough to get hold of before she stopped selling them. I shall be swapping them over in the troughs when I am sure I can part with the former. E. franchetii ‘Brimstone Butterfly’, with its flamingo-pink emerging foliage is excellent. Very strong and curiously showy, I like E. ‘King Prawn’. A hybrid raised by Julian Sutton of Desirable Plants, it is said to be a cross between E. latisepalum and a form of E. wushanense collected by Mikinori Ogisu, the famous Japanese plant collector with exquisite taste. Any of his discoveries have the letters Og and a number in their name and are well worth seeking out.

Epimedium acuminatum

Epimedium acuminatum

Epimedium ‘Egret’

Epimedium ‘Egret’

Epimedium ‘Amanogawa’

Epimedium ‘Amanogawa’

Hillside white seedling

Hillside white seedling

Once you get a number together their promiscuity will find tiny seedlings taking hold in cracks that are to their liking. This year I have two Somerset seedlings in flower for the first time, which I am judging to be worth bringing on – a dusky pink fargesii cross (main image), and a pale, elegant tall grower which looks to have fargesii and ‘Amanagowa’ in it. Right now I have my eye on one that has found a niche in the back wall where there is little else for it but moss and moisture. I am hopeful, of course, that this one will be special too. The excitement is in the wait.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 5 May 2018

Once again it’s that time of the year when the vegetable garden is providing slim pickings. The purple sprouting and kales are over, and the last of the stored potatoes have gone soft and started to sprout. While we wait for the broad beans, peas and lettuces to start producing we are left with the last of the gnarly roots – which were dug and stored in the barn three weeks ago – and a handful of leeks that were lifted to make way for another crop and are now standing in a trench in a neighbouring bed, looking rather lonely. When the vegetable beds look this barren the plants that are performing well are thrown into sharp relief, and guide us to what we should be eating.

The herbs appear first, many of them starting in earnest while it was still cold in early April. The parsley woke from its winter slumber to throw out lush branches of new leaf, while alongside it the chervil followed suit. This delicate umbellifer has a gentle aniseed flavour, similar to yet less pronounced than tarragon. I use it generously in salads, with new potatoes or to flavour a simple herb omelette. Like tarragon it works well with chicken and fish. However, its mild flavour is impaired by cooking, so it should always be added at the last moment to hot food. I keep us in regular supply by successional sowing every three weeks through the summer, always sowing more seed than needed since, like parsley, it can be shy to germinate. In the hedgerows its wild cousin, cow parsley (Anthriscus sylvestris), is also just coming up to flower. The flavour of wild chervil is slightly coarser, but makes a good foraged substitute. However, as with all foraged umbellifers you must be absolutely sure you are collecting the correct species, as many of them are highly toxic. Use a good field guide if you lack the confidence of a positive identification.

Chervil (Anthriscus cerefolium)

Chervil (Anthriscus cerefolium)

At the same time as the common sorrel (Rumex acetosa) appeared in the fields around us, the sorrel in the herb garden started shooting in earnest and is now producing far more than we can eat in salad alone. Garden sorrel is a cultivated form of the wild plant selected for larger, softer leaves and its sharp, lemon freshness is good with so many things at this time of the year. Like chervil it also works well with chicken, fish and eggs while, on its own it makes a clean, refreshing soup to awaken the winter palate. Sorrel is a hardy perennial and easy to grow from seed, but it also seeds prolifically, so when harvesting you should cut out the flowering stems or, if you have more than one plant as we do, cut them to the ground on rotation. They come back remarkably quickly.

Sorrel (Rumex acetosa)

Sorrel (Rumex acetosa)

Stracciatella is a traditional Roman soup served at the start of festive meals, particularly at Easter. When I was first working in London on a graduate’s wages I would eat bowlfuls of it at Pollo Bar, one of the many great Italian restaurants that Soho used to boast. Despite being nothing more than a bowl of stock with added egg, it was hot and filling and felt like it was good for you for the price. The proverbial meal in a bowl.

Although normally made with meat stock – chicken, pork, beef and veal are all used in Italy – I wanted to make a vegetable stock with our surfeit of root vegetables and leeks. Since the success of stracciatella is entirely dependent on the quality of the stock, which must be well-flavoured and complex, the vegetables were roasted before being simmered in water with fresh herbs and seasoning. Parmesan rind adds depth and savour to the vegetable broth. I keep a container of the rinds in the freezer for just this purpose.

Made from the last of the winter stores and the freshest of the new season herbs, a steaming bowl of this soup warms the soul as the heavy, cold rain falls once again outside the window.

INGREDIENTS

For the stock

100g each of:

Celeriac

Swede

Turnip

Parsnip

Carrot

1 small brown onion or a medium leek

2 large cloves garlic

1 small bay leaf

1 small sprig of thyme

1 small sprig of rosemary

2 sage leaves

A branch of parsley

A handful of chervil stalks

Olive oil

6 whole peppercorns

A pinch of chili flakes