An inevitable shift happens when the Tump, our plumpest field and the backdrop to the garden, is cut for hay. In the days that follow, the path that was mown into the meadow marks a bright green line in the stubble and stands as a memory of the daily walk we made through waist-high grasses. It takes a week or maybe two depending on the year for the land to re-green and with it the path slowly vanishes. The garden, meanwhile, tips from its high summer glory, the vibrancy of July infused with the feeling of the next season. In a countermovement, the grasses in the garden rise up amongst the perennials as if to compensate for the loss of the meadow beyond and with them the thistles that mark the month of August appear. The neon of the artichokes we left to flower in the kitchen garden and the echinops or globe thistles, of which we have three.

The first to become present is Echinops ritro ‘Veitch’s Blue’, which steps through the lavenders in an area we call the Herb Garden. It is the best behaved of those we grow here, standing at around a metre and never seeding like the majority of its cousins. The long-lived rosettes of thistly foliage, green on the upper side and silvery beneath, become completely dormant in winter and are relatively late to stir in spring. The leaves have a ‘look-but-don’t-touch’ quality about them, but they are perfectly easy to work amongst. Being sun lovers, the one thing they do not like is competition before they get head and shoulders above their neighbours. And this is why they do well here, the rosettes having the room to muster before the tightly clipped domes of the lavender start stirring.

The interest starts early as soon as the flowering growth shows itself in June. The depth of colour comes from the deepest indigo calyces, which are repeated countless times to form a mathematically perfect sphere. Being composites, each sphere is composed of many individual flowers, which open from the top down as they come into flower. A flowering stem will suspend each of the orbs in a galaxy that is particular to each plant. I have clustered several plants together in a mother colony with breakaway satellites amongst the lavender so that the intensity of one against the next varies as the flowers work against each other. The dark buds finally give way to denim blue as the globes are enlivened by flower.

One of the remarkable features of all echinops is their attractiveness to pollinators and they are alive with bees and nectar seeking insects, never more so than now when the meadows are down and our native wildflowers are on the wane. With this in mind, we have two more globe thistles in the main garden. I used to grow Echinops sphaerocephalus ‘Arctic Glow’ (main image) when I was a teenager where it threw rangy stems to shoulder height in the clearing we gardened amongst the trees of our woodland garden. I pined for sun then and the light we have here on our sunny slopes have yielded another plant all together, hunkered and stocky with no need for staking and rarely more than waist height.

‘Arctic Glow’ does have a mind of its own, though not horribly so, and its foliage is thistly. The rosettes take about a year to muster the strength to throw up a flowering stem once they have seeded, and seed they do. Prolifically and with the precision of a dart player. If you miss a seedling in the spring, do not underestimate the speed with which it sends down a taproot and takes hold in a neighbouring plant’s basal rosette. Once the taproot is in place the foliage is strong enough to muscle its way in and outcompete its host. However, this is to focus on the wrong qualities of the plant, as the decision to invite ‘Arctic Glow’ into the garden has also been a good one. The silvery buds give way to a grey-white sphere of flower, which contrasts here very beautifully with the smokiness of Nepeta nuda ‘Romany Dusk’. Seeding can be diminished by taking the whole plant to the ground after flowering, so you need to plan for the potential gap. The asters and the late arrival of Dahlia australis cover for it here, but I do leave a couple standing as they have proven themselves to be as short-lived here as they are pioneering.

This habit needs to be managed and the same can be said of the Russian globe thistle, Echinops exaltatus. This plant needs space and commitment and though I love it for its presence, I would not trust it to seed throughout the garden so it is also felled before it seeds. Lush green foliage, which fortunately is more or less devoid of spines, amasses volume early in the season and balloons exponentially as it races to flower. This is very exciting. The books say it stands at about 1.5m but on our rich ground here, it grows to two metres or more so it is gently staked with a hoop to prevent it from leaning. You do need to plan for it throwing shade on its neighbours that might not be up to rubbing alongside such a vigorous companion. I do this with earlier flowering Cenolophium and cover for the gap post-flowering with Japanese wind anemone and actaea.

Echinops exaltatus is is the last to flower here. The pale green spheres are luminous, tipped with silver and, just before the flowers open, the perfection of their symmetry repays close study. Slowly, this first week in the month, the orbs break into flower. First one and then another, the bees, hoverflies and beetles flocking to feast as more come on stream. I have them here with the fine spires of white Veronicastrum virginicum ‘Album’ and the August darkness of trees as their backdrop.

One day, I dream of having the space to let them go, to let them stand into the winter and lead a planting of pioneers that works on a grand and autonomous scale with white willow herb, romping cardoons, Alcea cannabina and and wild carrot as companions. For now, though, I am happy to put the time in to curtail their natural tendencies to roam and am happy that they are here to set the tone for beginning of the last fling of summer.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 1 August 2020

When we moved here from our Peckham garden with space to try a new plant palette, we set aside a section of the old trial garden to get to know a number of the David Austin Roses. I wanted to live with them day to day rather than vicariously through my clients’ gardens, so I took a trip up to the David Austin rose garden in Albrighton and spent an afternoon in the third week of June in the generous company of Michael Marriott, their rosarian. There is nothing like time spent with experts, or in seeing the plants right there in front of you, each with its own character and, once you had buried your nose in flower, its own perfume. Some spicy, others tangy and smelling of citrus or as fresh and clean as tea.

I had several requirements. I knew I would be using species roses in the wider landscape where they would sit more happily, but for cutting it was important that the roses were good performers and had a long season. I wanted plants that were disease-resistant, because I didn’t want to spray, and it was imperative that they had scent. What would be the point in having a bedside rose that simply sat prettily ?

I came away with a list of twenty four varieties ranging from white through cream and yellow, and then all shades of pink and on into apricot, orange and reds. Most were doubles with quartered blooms, because I wanted to have a little opulence, and it was also important that the foliage had good character. The first plants had five years in the old garden when I dismantled the trial beds to make way for the garden landscaping. At that point I rejected a few that were weak or not right here and replanted with new plants and a few new varieties up by the old barns. I like them here against the corrugated tin, planted in practical rows which suggest and allow for ease of picking.

The last nine years here they have shown me what they are made of. In general the yellows have done less well for us, but our West Country climate, with its heavy dews and year round dampness, may be the reason that a few have been prone to blackspot. The beautiful clear yellow ‘Graham Thomas’ succumbed here, though it has done well and been ‘clean’ for friends. ‘Charlotte’ has also failed and neither have been replaced because there is simply no point in having a sick rose when there are a host of others that are strong and healthy. I have struggled to keep a couple of reds and oranges too, but have been happy to spray twice with a sulphur-based fungicide early and mid-season to keep ‘Munstead Wood’ and ‘Summer Song’.

‘Munstead Wood’ is simply the best of the reds, deep and lustrous and beautifully perfumed like your memory of what a rose should smell like. Though not a strong grower, it responds well to being nurtured and I am prepared to do so for the reward. ‘Summer Song’ is perhaps my favourite of all in terms of colour, with a burnt orange flower and delicious zesty perfume. It too is weak and I would never recommend it in a planting scheme, but it can be forgiven for its less than athletic figure in the cutting garden. Cutting the roses regularly is a good opportunity to check on health and vigour. We dead head as we go to keep the flowers coming. I feed with organic chicken manure pellets after their first flush and this helps to keep them in good condition and plentiful right through to November. We have found that the Austin roses take a couple of years to settle in, but are fully up and running in year three.

Of those that have done well, ‘The Lark Ascending’ is by far the strongest and a firm favourite. Healthy and amassing a good six feet in a season, the foliage has the mattness of an old-fashioned rose. The flowers are delightful, semi-double, cupping open to reveal a boss of stamens they deteriorating elegantly. The semi-doubles and the singles last less well as cutting flowers but are better for pollinators and this combination of elements make it a good candidate for a mixed planting. The tea-rose scent is delicate, but its habits make it worth this minor compromise.

‘Mortimer Sackler’ is also open in character, with loose-petalled, shell pink flowers and an airy personality. Dark stems, delicate growth and fine foliage are more reminiscent of a chinensis rose. The scent is light, but it is a singularly graceful plant. Of all the David Austin roses that we grow, these last two are most relaxed in habit and would be easy in combination with plants like gaura or cenolophium. ‘Mortimer Sackler’ would also take well to being wall-trained.

‘The Lady of Shallot’ is one of the best cutting roses, strong and reliable and balanced as a shrub of about four feet. Lasting some time in a vase and beautifully proportioned, the soft orange is easy to use alongside pinks and yellows and its perfume, though recessive, is a fruity tea scent.

‘Lady Emma Hamilton’ is an excellent, strong-growing plant of similar colour to ‘The Lady of Shallot’, though a little more golden. However, it differs in the dark plum colouring that runs through the new foliage and tints the outside of the buds and then then suffuses the edges of each petal as the flowers age. The overall impression is rich and warm, while the zesty scent is strong and delicious.

‘Julbilee Celebration’ is an opulent rose and, although the weight of the flower tends to make for a plant that hangs its head (and more so in damp weather), its faded rose colour is unusual. There is enough salmon in it to bridge the pinks, but also a little yellow to act as a mediator between the yellows, apricots and oranges. The scent is proper old rose and, though it is a stiff, stocky grower, I like it immensely once it gets going.

I prefer strong pinks in a garden, campion pink or the electric pink of Dianthus carthusianorum. I do not gravitate towards soft, pale pinks but ‘Scepter’d Isle’ is a good clean pink and a very pretty rose in a bunch, although its scent, described as ‘myrrh’ is hard to pin down. ‘Gertrude Jekyll’ starts a strong deep pink fading as it ages and, although not such an attractive form as others, is by far the best of the roses for perfume. Pure rose and transporting. You only need a bud in a jar to work a room. She is the first of the roses to flower every year and reliable throughout the season.

‘A Shropsire Lad’ is by far the most vigorous with limbs that can easily reach six feet in a season and I suspect would make a better climber than a shrub. The flower is fully quartered when it is young, but loosens as it opens, with delicate, creamy flesh tones and a traditional tea rose scent.

Reaching to eight feet or so the clean, apple green foliage of ‘Claire Austin’ is a fine foil for the creamy white flowers, which are elegant and poised, but do bow gently under their own weight, so it makes for a better climber. I have grown it as such with some success in clients’ gardens, but it also makes a good, rangy shrub that would benefit from some support in a garden setting. The perfume is green and fresh and not remotely heady.

Although we grow two dozen of the extensive Austin range, my aim is to refine down to half that number, slowly letting the ones that reveal themselves to be right for our tastes to gently assert themselves. Cutting is a very nice way to do that. A regular connection and intimacy is always the best way to get to know the keepers.

Main image, left to right: The Lark Ascending, Claire Austin, Munstead Wood, The Lady of Shallot, Jubilee Celebration, Gertrude Jekyll (front), Scepter’d Isle (back), A Shropshire Lad, Lady Emma Hamilton, Summer Song, Mortimer Sackler

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 25 July 2020

After endless days of low cloud cover, chill winds and drizzle, suddenly the sun blazed yesterday and again today. Last night I dreamt of Greece.

Our planned Easter break had to be cancelled, of course, and neither of us have the stomach yet for travelling that far. Like many our relationship to international travel has changed over the past months, due both to quarantine requirements and the clear proof, as if any were needed, of the contribution flying makes to climate change when emissions plummeted after lockdown. Travelling overland and by sea have become our preferred means of getting away, but it will be some time before we feel confident enough to make the 4 day journey by train and ferry to our beloved island.

When I dream of our holidays in Greece food figures strongly in my memories and there is one dish in particular that I miss more than any other. Pythia is the local name given to the chick pea fritters that are more commonly known across Greece as revithokeftedes. They are doubtless related to falafel, but are lighter and fresher tasting, although recipes vary from region to region, village to village and family to family. In fact, one of our holiday pastimes is to judge who, this year, is making the best pythia. There are a couple of regulars who mantain total consistency from meal to meal and year to year, but every year there may be a surprise newcomer.

We have never tried to grow chick peas here, since they need a long season of heat for the peas to ripen. However, I was heartened to read this growing information recently, which suggests that with a sunny, sheltered position it is possible to get a substantial crop of green peas that are good to eat fresh. We learned a lesson this year, after planting our peas on the ‘frontline’ of the kitchen garden. After a slightly false start due to mice eating some of the first sowing, they were then slow to get going and, once they did, hated the hot winds of May and the cold winds of June equally, never really hitting their stride. The short-growing petit pois ‘Charmette’ fared the better of the two we grew, but only provided for around four meals, as the pods wizened on the plants before maturing. Early this morning, whilst picking the last of the very disappointing and elderly crop of Glory of Devon peas, I was wondering what to do with them, as they were too old to simply eat boiled. With visions of Greece still floating in my head I thought that they would make a good substitute for chick peas in a fresh, green version of pythia.

Last weekend I dug up the shallots and three weeks before that the first of the summer garlic, both of which feature in this recipe, as well as the cucumber and herbs which are all from the garden.

If you can’t find chick pea flour and have a Nutribullet type blender you can make your own from dried chick peas. It can also be found at suppliers of Indian foods as gram flour. You can, of course, use frozen peas in place of fresh, or broad beans or the traditional chick peas.

Makes 12, enough for 4 as a starter

250g shelled peas

1 shallot, finely chopped, about 40g

2 fat cloves of fresh garlic

A small handful of flat-leafed parsley, stalks removed

The leaves from two stems of fresh oregano, about 2 tablespoons

1 teaspoon ground coriander

1 long green chilli

The zest and juice of one lemon

8 tablespoons of chick pea flour

1 teaspoon of baking powder

Ice cold fizzy water

Salt and finely ground black pepper

1 small cucumber

100ml strained Greek yogurt

1 tablespoon mint, very finely chopped

1 tablespoon dill fronds, very finely chopped

1 clove of garlic

Salt

Flavourless oil for frying such as rapeseed or rice bran

Firstly grate the cucumber finely into a sieve. Sprinkle with some salt and leave to drain over a bowl while you make the pythia mixture.

Blanch the peas in boiling water for two minutes. Drain them well in a colander then put them with the shallot, garlic, herbs, coriander, chilli, lemon zest and juice into a food processor fitted with a blade. Pulse process until the mixture resembles coarse breadcrumbs. Tip the mixture into a bowl and season with salt and pepper.

Add the chick pea flour and baking powder and stir well to combine. Then add the fizzy water a little at a time until you have a mixture that is soft, but that still holds its shape on a spoon. If it looks too wet add more chick pea flour a little at a time. Leave to stand.

Put the oil into a high sided frying pan to a depth of about 2cm and heat to smoking point.

Using your hands squeeze as much liquid as possible from the cucumber. Put into a bowl with the yogurt and herbs. Grate the clove of garlic into the mixture, season with salt and stir.

When the oil is smoking test fry a small amount of the fritter mixture by gently lowering half a teaspoonful into the oil. It should sizzle and float and brown rapidly. Turn it over to brown the other side, then remove from the oil with a slotted spoon and drain on kitchen towel. Allow to cool a little before tasting, then adjust the seasoning if necessary.

Bring the oil back up to temperature, then take dessertspoonfuls of the mixture and gently lower them into the oil. Do not overcrowd them or they won’t develop a crisp exterior. I use a 22cm diameter, high sided skillet and cook three at a time. Fry for approximately a minute and a half each side until a deep, golden brown, turning them gently once. Remove from the oil with a slotted spoon allowing excess oil to drain back into the pan before moving them onto a small baking tray lined with absorbent kitchen paper. Put them into a warm oven while you cook the rest of the mixture.

Put three pythia on a plate for each guest, with a spoonful of tzatziki and a slice of lemon. Eat piping hot with a glass of something cold.

Recipe & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 18 July 2020

The Chinese meadow rue has been steadily working towards this moment. My favourite of first buds open and the majority yet to come. The plants grow close to the path and stand between the veranda and the garden. Deliberately, so that we are able to take in their delicacy and for the veil they draw between the immediate and the beyond.

Thalictrum ‘Splendide White’ is the albino form of its equally beautiful parent Thalictrum ‘Splendide’ which is mauve and yellow anthered. The white form is pale in all its parts. A clean, bright white with palest greenish-yellow anthers and apple green foliage which is as fine and as easy on the eye as maidenhair fern. Awakening later than most and coming into its own once its cousins have already peaked, the refined nature of its growth makes easy company, spearing through Bowles’ Golden Grass and providing a foil for the black Iris chrysographes that it goes on to eclipse. It is a good companion, taking very little room at ground level and light on its feet in the ascent. This year has seen it rising to six feet with midsummer moisture.

Though I know Thalictrum minus var. hypoleucum from the open woods of the Tokachi Millennium Forest in Hokkaido, I have never seen the Chinese meadow rue in the wild. I imagine they favour similar conditions in retentive ground in woodland glades or forest edges. Here our rich soil and the microclimate of company helps to emulate the coolness at the root that they desire. Teamed now with the dark thimbles of Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’ and – where I’m trying to keep it within bounds – the white willow herb, a little staking to prevent a topple once their flowers are fully open and weighting the stems keeps them holding the vertical.

Look into their wiry cage and countless perfectly spherical buds each hover in their own space forming, en masse, a pale and luminous cloud. Opening gradually from the inner parts of the veil, the pea-sized flowers cup long anthers that are thrust forward and hint at green. Though you might think its delicate nature would indicate an ephemeral presence, ‘Splendide White’ is anything but, the plants returning reliably come spring to spangle this part of the garden for four to six weeks of quiet glory.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 11 July 2020

Everything changes as June tips into July. The meadows, now tawny and seeding, begin to throw their second wave of flower. Knapweeds, scabious and the bedstraws with their clean and honied perfume. The yellow rattle is rattling with seed and letting us know that it won’t be long before we get a call from the farmer who will want to cut and bale the hay before the goodness goes out of it. We walk the arc of a path mown into The Tump to make the most of their last days, the Meadow Brown butterflies lifting ahead of us as we disturb the evening.

We leave the slopes behind the house uncut until the middle of August to compensate for the July cut in the broader landscape, but there is an inevitable handover that happens once the meadows are harvested and return to grazing. It was good to have taken our time to understand these rhythms before beginning the garden proper and, subliminally, I think I’ve planned for this moment as our focus comes back to the homestead. Back to harvesting in the kitchen garden and the orchard and back to the garden as it betters in this second half of summer.

We had a visitor late this week to mark this moment. It has been a curious year for not being able to share the garden with friends, to discuss the changes and the planned for and unplanned for happenings. You see a garden in altogether another light when you are not head down or distracted by the tasks that need doing. Showing a garden is time put aside to reflect and enjoy and, like going to an exhibition with a friend, their own personal reflections can often throw another light entirely on what you think. You learn through looking together and so on Thursday evening with perfect timing the light did its thing, the clouds parting at five, just before Tania’s arrival.

The garden has gone through a shift in the last week, the reach for the sky peaking to give way to colour. The Dierama mark the balancing point perfectly, spearing upward with the lengthening light of June and arching under the weight of their own flower in the long, drawn out days. The flowering stems, are fine and pliable, the flowers held in suspense, their mobility hypnotising, bobbing and flexing and rarely still.

It is clear why they have earned the name Angel’s Fishing Rods and I planned for the Dierama to line the path edges so that you cannot help but engage with their dance. The position on the front line and in the open is ideal for them and I chose ‘Blackbird’, ‘Cosmos’ and ‘Merlin’ to enjoy the darkest selections. Choosing the dark flowered forms rather than the pinks felt like an important move as the flowering of the Dierama comes with the first wave of strong colour. The curiousness of bi-coloured Kniphofia rufa and the acid green of Euphorbia ceratocarpa are not easily paired with colour that is not definite, so I was dismayed that, when they finally came to flower, the Dieramas were not what I had planned for. Clearly seed-raised and completely variable, a number of washed-out pinks will have to be ‘moved-on,’ but there have been a couple of surprises which have reframed my original palette. And not for the worse.

Central to the whole garden and taking pride of place is what I believe to be ‘Guinevere’. We circled around her for quite some time the other evening, returning more than once to take in a plant that is completely happy in its place and well coupled in the brightest part of the garden. Having grown Dierama before in a dense London garden, I quickly learned that they hate competition and that their spearing evergreen foliage should always have light right down to the base. I learned too that if you do get the position wrong and try to move them, they dislike the disturbance and will sulk for years or worse, dwindle away to nothing. A young plant grown into position and left to mature where it finds its feet is the surest way to happiness.

Hailing from the open meadows of South Africa, where they can and do get good summer rainfall, Dierama are happy with moisture as long as the ground doesn’t lie wet and cold in winter. That said, I have also grown them well in free draining soil and have only ever failed where they have struggled with competition, as their main considerations are light and air. Both elements that we have plentifully here so their dance is a fine one, holding the eye and our attention as we circle back into the high summer garden.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 3 July 2020

A tsunami of soft fruit is about to break. The gooseberries are first and so this weekend I’ll be crouched on a milking stool in the cool shade of the blackcurrant bushes picking ‘Hinnomaki Green’. As I pick, the blackcurrants brushing my shoulders will be a constant reminder that soon there will be consecutive weekends of picking. We have three varieties, each with different fruiting times to extend the season and the harvest. Last year around this time I found our dear friend Sophie (AKA Champion Picker) among the bushes at daybreak on a post heatwave misty morning, picking and breakfasting in tandem. A whole bush stripped before coffee time is par for the course for Sophie. This year it will be down to me, Dan and the lucky birds.

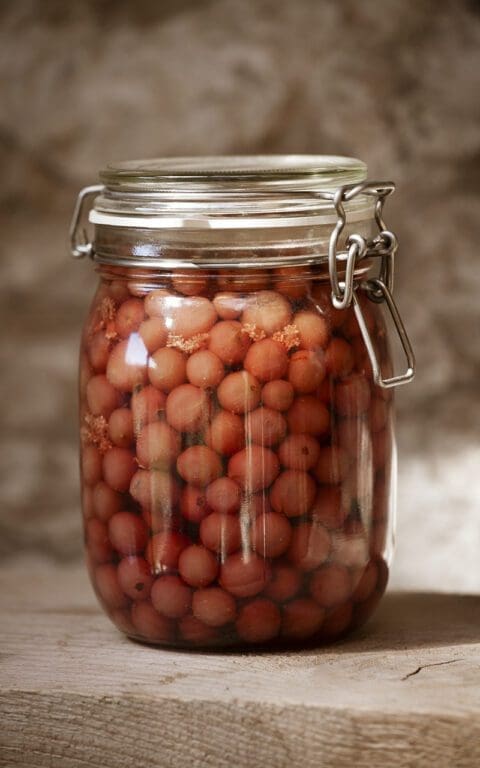

The gooseberry ‘Hinnomaki Red’ take a little longer to reach maturity than the green, which is a relief, since a Kilner jar full of the remainder of last year’s harvest has been judging me silently from a shelf in the pantry for a while now. We always reach this point in the year when the approaching harvest starts to throw a very different light on the frozen ends of last year’s crop in the freezer. A quick stock take this week revealed two half carrier bags full of gooseberries (green) and blackcurrants respectively, a huge Tupperware full of redcurrants and damsons. Just enough to stew for a week of breakfasts, unlike last year’s June’s freezer clearance which resulted in a memorably messy and sticky summer’s day making damson ketchup, damson chutney, damson shrub and damson fruit leather, again with Sophie, and other willing helpers.

Now that the kitchen garden is beginning to produce in earnest we are really missing our regular weekend housefuls to help harvest, prepare and cook food from the garden together, then share it at a large and usually raucous table late into the evening.

The absence of visitors in this unusual year has also meant that I have found far less reason to make puddings in recent months. When we do end a meal with something sweet it is invariably with some variety of stewed fruit and a spoonful of yogurt, sometimes cream. However, with that jar of red gooseberries on my conscience, a quick pass through the kitchen garden revealed that the whitecurrant and tayberry were dripping with jewel-like fruit, and a summer pudding of this and last summer’s fruits started to materialise. Sweetened with some elderflower cordial made last week and using up the end of a stale loaf of bread that was consigned to the freezer for breadcrumbs several weeks ago and is now taking up valuable space. Space that will very soon be filled by a new generation of soft fruit.

INGREDIENTS

750g mixed soft fruit – raspberry, blackcurrant, strawberry, gooseberry, bayberry, loganberry, redcurrant, whitecurrant

3 tablespoons elderflower cordial

3 tablespoons light honey or caster sugar

A couple of heads of elderflowers

7 slices 1cm thick of slightly stale good white bread

METHOD

Put any fruit that needs cooking (blackcurrants and gooseberries) into a lidded pan on a very low heat with two tablespoons of water and the honey or sugar. Cook until they start to burst and release their juices. Remove the pan from the heat and add the rest of the fruit. Remove the elderflowers from their umbels by dragging the tines of a fork through them over the pan of stewed fruit. Stir, return the lid and leave to stand until cool.

Cut a circle from one slice of bread to fit the bottom of a 1 litre pudding basin. Cut all but two of the remaining slices of bread into triangles of the same height as the pudding basin and use to line the inside of the basin. Fill any gaps with smaller pieces of torn bread. Once the basin is lined pour all of the stewed fruit (reserving three tablespoons) into the cavity. Press down with the back of a metal spoon and smooth level. Cut the remaining slices of bread into as few pieces as possible to make a lid that fits on top of the stewed fruit.

Take a side plate the same diameter as the top of the basin and put it on top of the pudding. Then secure the plate well. I use extra strong elastic bands or well-tied string to exert pressure on the pudding, but you can weight the plate down with a heavy jar. Stand the pudding basin in dish to catch any juice and put in the fridge overnight or for a minimum of 4 hours. Put the reserved stewed fruit into a small pan with a couple of tablespoons of water and one of honey or sugar and bring to a simmer. Press through a sieve and reserve.

When ready to turn out slide a blunt knife between the pudding and the basin until it is loosened. Take a deep serving dish and invert it over the pudding basin. Holding the basin and plate tightly together with both hands invert the whole lot and shake gently but firmly. You should hear the pudding slip out of the basin and onto the plate with a satisfying slurp. Carefully lift off the basin. Pour over the reserved fruit sauce. Decorate with more fruit if you like and serve with cold pouring cream.

Recipe and photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 27 June 2020

The sweet peas are an investment. A good one with the promise of marking summertime, but one that is not without a requirement for continuity and a little-and-often attention. The rounded, manageable seed is easy. A finger pushed into compost and three seeds per pot for good measure. Sown either in the autumn and overwintered in the frame for a little protection for the strongest plants and earliest flower or, alternatively, at the first glimmer of spring in February. You have to watch if the mice are not to eat the freshly sown seed before it has even germinated and, although perfectly hardy, they like good living once ready to go out in April. They require good ground, with manure or compost and plenty of moisture to send their searching growth up into a carefully managed cage of supports. We use hazel twiggery from the coppice here. Helping their ascent, so that their soft tendrils are trained within easy reach for picking, another part of the daily vigil. And finally, once they start to bloom, you need to keep on picking to keep the flowers coming if they are not to go to seed.

All in all the rewards are forever worth it and the jug sitting beside me, with the whole room perfumed of summertime is testament. Their vibrancy is the personification of long days spent outside doing and the elongated evenings that stretch ahead until bedtime. We spend this valuable time looking and find the evenings and early morning the best time to pick them, for the cool flushes their flower and helps in keeping for longer. The evening bunch for the bedside and the morning bunch for the kitchen table. Pick and you can keep on picking every other day and, when the plants finally begin to run out of energy in August, you will be sure to feel the next season coming. The weight of harvest and in the case of the Lathyrus, the desire to go to seed, which we make allowance for when the stems get too short to pick so that we can save some.

We grow two batches of sweet peas now. Named varieties of the Old Fashioned sweet peas, which we buy new every year from Roger Parsons and Johnson’s. Selected for their perfume and not length of stem we grow them up informal hazel wigwams in a strip of land we call the cutting garden. These are an ever-changing selection as we add to and subtract from a variable list as we move through new varieties and revisit ones we’ve grown to love. These selections have plenty of Lathyrus odoratus blood coursing through their veins and we like the fact that you can feel the parent and that they have not been overbred at the expense of their stem length, flower size or perfume.

Set to one side and grown amongst the perennials in the main garden are the pure Lathyrus odoratus. We keep them apart because the seed was collected by the plantsman and painter Cedric Morris on one of his journeys to Sicily. The direct line has been carefully handed down to custodians who knew the importance of continuity. First, directly from Cedric to his friend Tony Venison, former Gardens Editor of Country Life, and then from Tony to his friend Duncan Scott. Meeting Duncan was a chance happening, as he is the neighbour of a client who thought we should connect. Duncan knew of my friendship with Beth Chatto, who in turn had learned directly from Cedric and had many of his plants in her nursery.

Duncan’s seed was handed over in a brown paper bag with the inscription ‘Cedric’s Pea. Lathyrus odoratus, collected in Sicily’. In turn I have recently had the pleasure of sending seed on to Bridget Pinchbeck who has taken on the responsibility of restoring Benton End, Cedric’s house and garden in Suffolk, to become a creative outpost of The Garden Museum. A full circle made in not too many leaps of the gardeners’ weave and easy generosity.

I am very happy to help keep the line alive and to pass it on, as we have spent much time looking through Cedric’s eyes over the years. First with plants that Morris gave with stories of their provenance to Beth Chatto and her in turn to me. And then through his dusky almost-grey and pink selections of Papaver rhoeas and latterly his Benton Iris which we grow here and treasure. Lathyrus odoratus was first introduced in 1699 by the monk Francis Cupani, the name which you will often find the pea listed under. I wonder whether Morris made his trip to Sicily in Cupani’s footsteps to find the pea for himself ? Regardless, it is good to imagine the find and relive his undoubted excitement at it. The vibrancy of the flower, with its vivid coupling of purple falls, wine red standards and the halo of unmistakable perfume.

It is Cedric’s lathyrus which is the first of our sweet peas to flower. A whole two weeks earlier than the named varieties and still the most perfumed of all. When we walk the garden in the late half-light of June, it is with an invisible orbit of scent that stops you on the path. The late light or early morning are the best times to see their colour. Clear and sumptuous and well worth the effort of continuity.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 19 June 2020

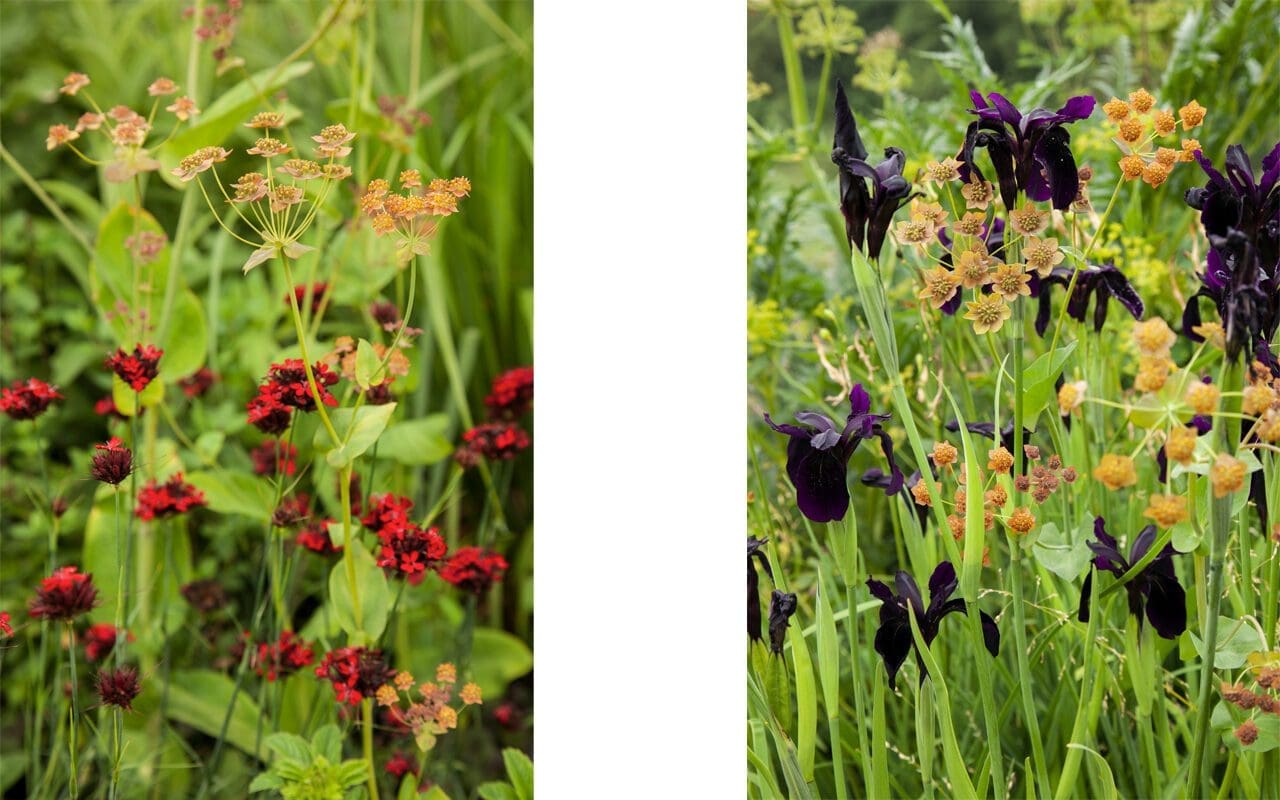

I first encountered Bupleurum longifolium ‘Bronze Beauty’ around twenty years ago at Stoneacre in Kent. At the time our recently made friends Richard Nott and Graham Fraser were the National Trust’s tenants and, as its custodians, they had woven a thoughtful new layer into the garden that played to their interest in colour. They had recently exchanged their lives running Workers For Freedom, their successful fashion label, for a new life in the country. Richard was studying painting and Graham, the history of both the garden and the house, which was restored in the 1920’s by Aymer Vallance, the Arts & Crafts architect and biographer of William Morris.

Together they took to the garden, moving easily from one creative discipline to the next, enjoying the fact that the worlds were easily interchangeable. It was precious time that we spent there and, with weekends away from our south London lives, in the idyllic setting of this place it felt like there was time to talk. We workshopped the planting and in the easy world of this garden the conversations moved effortlessly back and forth to cover all manner of territories. With life experience that we were yet to have, our new friends provided good council and helped build confidence about doing what was right for us and being sure of our direction.

Stoneacre is a garden of rooms that give way one from the other as you walk around the half-timbered hall house. A straight stone path sloped gently to the front door and they had dug up the lawn to either side and planted a pair of gauzy, golden borders that rose in early June to shoulder height with the shimmer of giant oat grass (Stipa gigantea). As you walked the path the detail in the planting revealed itself. Hemerocallis ‘Corky’, a delicate daylily with a dark reverse to the petal, provided the base note of gold. There was saffron Crocosmia × crocosmiiflora ‘George Davison’ and later Rudbeckia fulgida var. sullivantii ‘Goldsturm’, but there was a secret ingredient that provided the planting with a burnish. The bupleurum hovered amongst it all as a mutable undercurrent, a presence that was hard to detect at first until you had tuned your eye, but once you had it, it was the thing that drew you in and held you.

A clutch of seedlings found their way back to the garden in Peckham where they seeded about obligingly. Never moving further than the cast from a bent stem in high summer, but finding their niche wherever they like the territory, the tiny seedlings are easily distinguished in spring. Brilliant lime green cotyledons, two narrow slashes, appear early in the season. They arrive in a rash where they find open ground and soon form a bright first leaf the shape of a paddle. Where there is light and not too much competition they spend their first year hunkering to form a neat rosette. In the second year they throw the first flowering growth, sending up slender stems in early summer with a dusty bloom that softens their presence. By the middle of May the first umbels are filled out and standing tall and free of foliage. Finely spoked they throw just enough florets skywards, each with a neatly cut ruff and an inner button of stamens.

The shifting colour of ‘Bronze Beauty’, the form most commonly available, is hard to pin down ranging as it does from cinnamon to ochre to tan, but it compliments everything. I have not found a companion I do not like it with. I will determine a combination that I think will work well, but its easy nature will throw it into new territory together with something you simply hadn’t or wouldn’t have thought of. I am very particular about colour, but I rarely find it appearing anywhere that I find it jarring or out of place.

Advice if you are reading up about Bupleurum longifolium is to plant it in an open, sunny position. Yes, the low rosette enjoys light and suffers if it is overhung by neighbours, but we have found here, where we have all day sunshine, that it prefers to set seedlings on the shady side of the bed and those in full glare do less well. I think ‘open meadow’ when I plant it, so that it can rise up in company, but not so much that it feels overcrowded.

Although it is now finding its own way in the garden and is never competitive like its acid-yellow cousin, Bupleurum falcatum, which we also grow, the plants last three to five years and then hand over to the next generation. I always have a pot full of seedlings in the frame for good measure. They make easy additions where you might suddenly find yourself with a gap come spring. Always sow fresh, as all umbellifers (Apiaceae) do not last if kept and overwinter with a little protection. It was one of these pots of seedlings that found their way back to Richard and Graham a few years ago when they left Stoneacre to make their own garden at a new home on the south coast. An easy gift to return for such a treasured introduction.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 13 June 2020

A tide of ox-eyes have surrounded us, lapping up the banks that come to meet the house at the front and running down the centre of the track at the back to make it impassable. I cannot bring myself to mow the strip that runs to the barns when the meadows are up, in part because they mark this moment. They stand bright, aloft and alone on stalks that raise them into their own space in the meadow. Moving as one when caught in the breeze, each flower is a point of individual brightness but together they flare, so that all you see is whiteness.

Leucanthemum vulgare is a simple plant, happiest when pioneering and taking new ground. The profligate seed, produced on youngsters that are often not even a year old, is light enough to travel, perhaps not far but far enough to seize open ground. Germinating as soon as the weather dampens with September dews, this year’s seed will already be hunkered down and big enough to cope with winter. They have the start they need to be ahead of the race the following summer and their precocious behaviour will see an explosion of daisies for two years or so. Then the knit they have so helpfully made to seal bare soil will be colonised by the slower to establish meadow plants which ease their hold and dim their presence.

We seeded the ground around us after the landscaping was complete in the autumn of 2016 so the daisies are still in their dominant period. They grow so densely in parts that you have to squint on a bright day. By night they bounce the moonlight, brightening the ceilings in the house and earning my favourite name, the Moon Daisy. When growing as thickly as they do in the early years, you begin to wonder if anything else has the room to form an association, but they live fast and die young and are then content to have a lighter presence.

I used their easy nature to my advantage when we were addressing the ground that had been thrown up after making the pond at Home Farm. Frances, my friend, client and collaborator, was keen to blend the pond seamlessly with the landscape beyond and so we sowed meadow to the rear of the pond and took the gravel from the drive down over the gentle slope that met the pond in the hollow which we softened by seeding the ox-eyes were directly into it. We let it have its reign and within a year the pond sat in a sea of whiteness that met easily with the meadow and the wild carrots that proliferated there. It was an extraordinary place to pick your way through to the dark water. So simple and yet with so much life, return and generosity on the part of the daisies. We left them to blacken once they waned so that you saw the water again through the ghost of spent stems and then cut them back in September. An easy job with a strimmer or a scythe. A gentle weed in the autumn to remove seedling grasses was all we needed to do to retain the grand gesture.

Where we have over-seeded the old pasture here, their presence is entirely different. Seizing a window in the meadow is more difficult, so they smatter lightly where the Yellow Rattle diminishes the dominance of the grasses. The old pasture keeps the daisies in their place though, the closed system preventing the pioneer’s behaviour. They appear here and there and in lighter colonies where they find an opportunity, but are every bit as beautiful for fitting in and being happy to not even hint at world dominance.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 6 June 2020

The opium poppies have been growing into the lengthening evenings, to race skyward and seize this early window of first summer. They come from nowhere it seems and typify the current feeling of the garden burgeoning.

Their seedlings are already visible in March and one of the first to germinate into open ground. Blue-green and easily distinguished, they take the disturbed places where there will be a gap to ascend into the very moment the weather warms. Being winter hardy and germinating the moment the season turns with the promise of spring, they have the advantage, hunkering down and establishing good roots and core strength. In truth there are several rounds of germination as seed is brought to the surface whilst cultivating, weeding or clearing the winter garden to expose fresh ground, but the first are the strongest, bulking up in April and muscling out anything nearby that might show a glimmer of tardiness. Their precocious behaviour extends to their siblings and you will need to thin a colony if you are after plants that are muscular and soaring.

I grow a black opium poppy here and it is my one and only. A single form and a chance find that I made when cycling to work once in my early twenties. They were standing tall alongside a black wooden bungalow in Hampshire. Black on black, fluttering against the stained shiplap. If I hadn’t been looking in the way that you do when you are under your own steam, I would have missed them completely. It was immediately clear, even at distance, that they were special so I plucked up the courage and knocked at the door to ask for seed. The owner, seeing I was smitten, took my name and address and later that summer an envelope arrived with the beginnings of a now very long association. It is one that I have nurtured annually, seeding a few every year in a new place for good measure and gifting to friends and clients that I know will keep the strain pure.

Although there are other named forms of dark opium poppy, several double blacks and the deep plum ‘Lauren’s Grape’ for instance, I’ve not seen another that is quite as dark and inky throughout. To maintain the strain, I have been territorial. I have never introduced another coloured opium poppy into a garden where I have been cultivating them and any that show the remotest sign of reverting are pulled before they can pollinate a dark one nearby. I look nervously on to neighbours up the lane who have them growing freely in their garden in every shade of mauve and pink, but breathe easy that, in the ten years we’ve been here, the bees that busy themselves there must be on another flight path.

After moving them here from Peckham, I cast the seed down into the freshly turned ground of our virgin plot. Broadcast in February, the plants were up in flower by June and providing me with a new and plentiful seedbank by the middle of July. Those seeds have now found their way into the compost heap where they are content to sit dormant until they are exposed again to light and potentially new places to conquer. We had a good colony in the asparagus bed a couple of years ago, amongst the roses and throughout the kitchen garden and I am now finding seedlings in the paths that must have been dropped whilst we were clearing the garden.

The chance happening of the pioneer seedling is always heartening and we leave a few in a new place every year for the delight in the new. The first seedling to flower this year has been living with us closely alongside our covered terrace. I saw the seedling had found a home in the late winter and wondered if it would be one that would survive our lines of desire into the garden. It has, soon growing big enough to negotiate and with the promise of this very moment that is seeing it suddenly present. A filling out of blue-green buds and then, one day, a tilt in the neck of the bud to indicate readiness.

The mornings bring the flowers, crumpled at first and then expanding like dragonfly wings do when they hatch. Dark satin petals cup pale stamens and bees soon find them, noisily working in laps, the enclosure of petals amplifying the sound of their frenzy. The flowers last two to three days at most, but there are enough to run a glorious fortnight whilst the balance shifts from buds to seedpods pods fattening and tilting skyward to show you that they have nearly reached their goal. When the leaves suddenly wither and the life force of the plant is gone you see that the pepper-pot seedpods are ripe and beginning to rupture. We leave a few standing for the joy of continuity, the mission accomplished, and scatter the rest for the pleasure of helping them extend their territory.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 30 May 2020

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage