Chasmanthium latifolium

As a way back into the garden this morning we have picked a posy to mark a feeling of this change. The Chasmanthium latifolium are probably at their best, coppery-bronze and hovering above their still lime-green leaves. The perfectly flat flowers appear to have been pressed in a book. Like metallic paillettes they shimmer and bob in the slightest of breezes. I must admit to not having understood the requirements of this plant until recently and, though it is adaptable to a little shade and sun, it likes some shelter to flourish. Where I have used it in China in the searing heat of a Shanghai summer it has done superbly, spilling in a fountain of flower held well above the strappy foliage. It must like the humidity there. In the UK I have found it does best with some protection from the wind. My best plants here are on the leeward side of hawthorns, those in the same planting to the windward side have all but failed. It is a grass that is worth the time and effort to make its acquaintance.

Though the seedheads which mark the life that come before them now outweigh the flower in the garden, we have plenty to ground a posy. Scarcity makes late flower that much more precious and I like to make sure that we have smatterings amongst the late-season grasses. Brick-red schizostylis, flashes of late, navy salvia and clouds of powder blue asters pull your eye through the gauziness. The last push of Indian summer heat has yielded a late crop of dahlia, which have yet to be tickled by cold. I have three species here in the garden specifically for this moment. All singles and delicate in their demeanour. The white form of Dahlia merckii and the brightly mauve D. australis have shown their cold-hardiness and remain in the ground over winter with a mulch, but the Dahlia coccinea var. palmeri in this posy is new to me.

Chasmanthium latifolium

As a way back into the garden this morning we have picked a posy to mark a feeling of this change. The Chasmanthium latifolium are probably at their best, coppery-bronze and hovering above their still lime-green leaves. The perfectly flat flowers appear to have been pressed in a book. Like metallic paillettes they shimmer and bob in the slightest of breezes. I must admit to not having understood the requirements of this plant until recently and, though it is adaptable to a little shade and sun, it likes some shelter to flourish. Where I have used it in China in the searing heat of a Shanghai summer it has done superbly, spilling in a fountain of flower held well above the strappy foliage. It must like the humidity there. In the UK I have found it does best with some protection from the wind. My best plants here are on the leeward side of hawthorns, those in the same planting to the windward side have all but failed. It is a grass that is worth the time and effort to make its acquaintance.

Though the seedheads which mark the life that come before them now outweigh the flower in the garden, we have plenty to ground a posy. Scarcity makes late flower that much more precious and I like to make sure that we have smatterings amongst the late-season grasses. Brick-red schizostylis, flashes of late, navy salvia and clouds of powder blue asters pull your eye through the gauziness. The last push of Indian summer heat has yielded a late crop of dahlia, which have yet to be tickled by cold. I have three species here in the garden specifically for this moment. All singles and delicate in their demeanour. The white form of Dahlia merckii and the brightly mauve D. australis have shown their cold-hardiness and remain in the ground over winter with a mulch, but the Dahlia coccinea var. palmeri in this posy is new to me.

Dahlia coccinea var. palmeri

Dahlia coccinea var. palmeri

Rudbeckia subtomentosa ‘Little Henry’

I hope it is hardy enough to stay in the ground here. As soon as frost blackens the foliage, each plant will be mulched with a mound of compost to protect the tubers from frost. Distinctive for its feathered, ferny foliage and reaching, wiry limbs, this first year has shown my plants attaining about a metre, two thirds of their promise once they are established. This is not a showy plant, the flowers sparse and delicately suspended, but the colour is a punchy and rich tangerine orange, the boss of stamens egg-yolk yellow. We have it here with Rudbeckia subtomentosa ‘Little Henry’, which is also how it is teamed in the garden. ‘Little Henry’ is a shorter form of R. s. ‘Henry Eilers’ and, at about 60 to 90cm, better for being self-supporting. Usually I shy away from short forms, the elegance of the parent often being lost in horticultural selection, but ‘Little Henry’ is a keeper. They have been in flower now since the end of August and will only be dimmed by frost. Where you have to give yourself over to a Black-eyed-Susan and their flare of artificial sunlight, the rolled petals of ‘Little Henry’ are matt and a sophisticated shade of straw yellow, revealing just a flash of gold as the quills splay flat at the ends.

Rudbeckia subtomentosa ‘Little Henry’

I hope it is hardy enough to stay in the ground here. As soon as frost blackens the foliage, each plant will be mulched with a mound of compost to protect the tubers from frost. Distinctive for its feathered, ferny foliage and reaching, wiry limbs, this first year has shown my plants attaining about a metre, two thirds of their promise once they are established. This is not a showy plant, the flowers sparse and delicately suspended, but the colour is a punchy and rich tangerine orange, the boss of stamens egg-yolk yellow. We have it here with Rudbeckia subtomentosa ‘Little Henry’, which is also how it is teamed in the garden. ‘Little Henry’ is a shorter form of R. s. ‘Henry Eilers’ and, at about 60 to 90cm, better for being self-supporting. Usually I shy away from short forms, the elegance of the parent often being lost in horticultural selection, but ‘Little Henry’ is a keeper. They have been in flower now since the end of August and will only be dimmed by frost. Where you have to give yourself over to a Black-eyed-Susan and their flare of artificial sunlight, the rolled petals of ‘Little Henry’ are matt and a sophisticated shade of straw yellow, revealing just a flash of gold as the quills splay flat at the ends.

Ipomoea lobata

We have waited a long time this year for the Ipomoea lobata as it sprawled, then mounded and all but eclipsed the sunflowers. We always had a pot of this exotic-looking climber in our Peckham garden, but I have not grown it here yet and have been surprised by the amount of foliage it has produced at the expense of flower. Nasturtiums do this too in rich soil and, if I am to have earlier flower in the future, I will have to seek out an area of poorer ground. That will not suit the sunflowers, but I will find it a suitable partner that it can climb through. It is very easy from seed. Sown in late April in the cold frame and planted out after risk of frost, this is a reliable annual, or at least I thought so until I presented it with my hearty soil. Though late to start flowering this year, it also keeps going till the first frosts, its lick and flame of flower well-suited to the seasonal flare.

Ipomoea lobata

We have waited a long time this year for the Ipomoea lobata as it sprawled, then mounded and all but eclipsed the sunflowers. We always had a pot of this exotic-looking climber in our Peckham garden, but I have not grown it here yet and have been surprised by the amount of foliage it has produced at the expense of flower. Nasturtiums do this too in rich soil and, if I am to have earlier flower in the future, I will have to seek out an area of poorer ground. That will not suit the sunflowers, but I will find it a suitable partner that it can climb through. It is very easy from seed. Sown in late April in the cold frame and planted out after risk of frost, this is a reliable annual, or at least I thought so until I presented it with my hearty soil. Though late to start flowering this year, it also keeps going till the first frosts, its lick and flame of flower well-suited to the seasonal flare.

Rosa ‘Scharlachglut’

Roses that flower once and then hip beautifully are worth their brevity and we have included R. ‘Scharlachglut’ here, a single rose that I wrote about in flower earlier this year. The hips are much larger than a dog rose, but retain their elegance due to the length of the calyces, which put a Rococo twist on these pumpkin-orange orbs. Despite its ornamental quality when flowering, it is a plant that I am happy to use on the periphery of the garden and one that, in its second incarnation, I can be sure of seeing the season out.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 20 October 2018

Rosa ‘Scharlachglut’

Roses that flower once and then hip beautifully are worth their brevity and we have included R. ‘Scharlachglut’ here, a single rose that I wrote about in flower earlier this year. The hips are much larger than a dog rose, but retain their elegance due to the length of the calyces, which put a Rococo twist on these pumpkin-orange orbs. Despite its ornamental quality when flowering, it is a plant that I am happy to use on the periphery of the garden and one that, in its second incarnation, I can be sure of seeing the season out.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 20 October 2018 We are on holiday for two weeks and so leave you with some recent images of the garden to keep you going until we return.

Selinum wallichianum, Sanguisorba ‘Red Thunder’, Salix purpurea ‘Nancy Saunders’ and Anemone x hybrida ‘Honorine Jobert’

Selinum wallichianum, Sanguisorba ‘Red Thunder’, Salix purpurea ‘Nancy Saunders’ and Anemone x hybrida ‘Honorine Jobert’

Amicia zygomera and Agastache nepetoides

Amicia zygomera and Agastache nepetoides

Rudbeckia subtomentosa ‘Little Henry’ and Agastache nepetoides

Aster umbellatus, Persicaria amplexicaule ‘Blackfield’, Salvia ‘Jezebel’ and foliage of Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’

Aster umbellatus, Persicaria amplexicaule ‘Blackfield’, Salvia ‘Jezebel’ and foliage of Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’

Agastache ‘Blackadder’, Verbena macdougallii ‘Lavender Spires’ and Persicaria amplexicaule ‘September Spires’

Agastache ‘Blackadder’, Verbena macdougallii ‘Lavender Spires’ and Persicaria amplexicaule ‘September Spires’

Digitalis ferruginea, Achillea ‘Mondpagode’ and Scabiosa columbaria ssp. ochroleuca

Digitalis ferruginea, Achillea ‘Mondpagode’ and Scabiosa columbaria ssp. ochroleuca

Hesperantha coccinea ‘Major’

Hesperantha coccinea ‘Major’

Anemone hupehensis var. japonica ‘Splendens’ and Aster ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’

Anemone hupehensis var. japonica ‘Splendens’ and Aster ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’

Colchicum speciosum ‘Album’

Colchicum speciosum ‘Album’

Chasmanthium latifolium and Aster ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’

Chasmanthium latifolium and Aster ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’

Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 6 October 2018

Grasses were always going to be an important part of the garden. They make the link to the meadows and fray the boundary, so it is hard to tell where garden begins and ends. On our windy hillside, they also help in capturing this element, each one describing it in a slightly different way. The Pennisetum macrourum have been our weather-vanes since they claimed the centre of the garden in August. Moving like seaweed in a rock pool on a gentle day, they have tossed and turned when the wind has been up. The panicum, in contrast, have moved as one so that the whole garden appears to sway or shudder with the weather.

Though the pennisetum took centre stage and needed the space to rise head and shoulders above their companions, they are complemented by a matrix of grasses that run throughout the planting and help pull it together from midsummer onwards. Choosing which grasses would be right for the feeling here was an important exercise and the grass trial in the stock beds helped reveal their differences. At one end of the spectrum, and most ornamental in their feeling, were the miscanthus.

Clumping strongly and registering as definitely as a shrub in terms of volume, I knew I wanted a few for their sultry first flowers and then the silvering, late-season plumage. It soon became clear that they would need to be used judiciously, for their exotic presence was at odds with the link I wanted to make to the landscape here. At the other the end of the spectrum were the deschampsia and the melica, native grasses which we have here in the damp, open glades in the woodland. We have used selections of both and they have helped ground things, to tie down the garden plants which emerge amongst them.

Calamagrostis x acutiflora ‘Karl Foerster’

Calamagrostis x acutiflora ‘Karl Foerster’

Molinia arundinacea ssp. caerulea ‘Transparent’

Molinia arundinacea ssp. caerulea ‘Transparent’

Falling between to two ends of the shifting scale, we experimented with a range of genus to find the grasses that would provide the gauziness I wanted between the flowering perennials. As it is easy to have too many materials competing when choosing your building blocks for hard landscaping, so it is all too easy to have too many grasses together. Though subtle, each have their own function and I knew I couldn’t allow more than three to register together in any one place. Tall, arching Molinia caerulea ssp. arundinacea ‘Transparent’ that is tall enough to walk through and yet not be overwhelmed by would be the key plant at the intersection of paths. The fierce uprights of Calamagrostis x acutiflora ‘Karl Foerster’, scoring thunderous verticals early in the season and then bleaching to longstanding parchment yellow, would need to be given its own place too in the milking barn yard. I needed something subtler and less defined as their complement in the main garden.

Our free-draining ground and sunny, open position has proved to be perfect for cultivars of Panicum virgatum or the Switch Grass of American grass prairies. We tried several and soon found that, as late season grasses, they need room around their crowns early in the season if they are not to be overwhelmed. Late to come to life, often just showing green when the deschampsia are already flushed and shimmering with new growth, it is easy to overlook their importance from midsummer onwards. I knew from growing them before that they like to be kept lean and are prone to being less self-supporting if grown too ‘soft’ or without enough light, but here they have proven to be perfect. Bolting from reliably clump-forming rosettes, each plant will stay in its place and can be relied upon to ascend into its own space before filling out with a clouding inflorescence.

Panicum virgatum ‘Cloud Nine’. The original stock plant is in the centre.

Panicum virgatum ‘Cloud Nine’. The original stock plant is in the centre.

Panicum virgatum ‘Cloud Nine’

Panicum virgatum ‘Cloud Nine’

I tried several and, with the luxury of having the space to do so, some proved better than others. The largest and most dramatic is surely ‘Cloud Nine’. My eldest plant, the original, remains in the position of the old stock bed and the garden and younger companions were planted to ground it. This was, in part, due to it already being in the right place, for I needed a strong presence here where I’d decided not to have shrubs and they have helped with their height to frame the grass path that runs between them and the hedge along the lane. By the time the stock beds were dismantled we were pleased not to have to move it, because the clump is now hefty, and a two man job to lift and move it.

I first saw this selection in Piet Oudolf’s stock beds several years ago, where it stood head and shoulders above his lofty frame. Scaled up in all its parts from most other selections, the silvery-grey leaf blades are wider than most panicum and very definite in their presence. Standing at chest height in August before showing any sign of flower, it is the strongest of the tribe. Now, in early autumn, its pale panicles of flower have filled it out further, broadening the earlier bolt of foliage. If it was a firework in a firework display of panicum, it would surely be the last, the scene-stealer that has you gasping audibly. I like it too for the way it pales as it dies and it stands reliably through winter to arrest low light and make a skeletal garden flare that is paler in dry weather and cinnamon when wet.

Panicum virgatum ‘Rehbraun’

Panicum virgatum ‘Rehbraun’

I have three other panicum in the garden, which are entirely different in their scale and presence. Though it has proven to be larger than anticipated in our hearty ground and will need moving about in the spring to get the planting just right, I am pleased to have selected ‘Rehbraun’. Calm, green foliage rises to about a metre before starting to colour burgundy in late summer. The base of redness is then eclipsed by a mist of mahogany flower, which when planted in groups, moves as one in the breeze. I have it as a dark backdrop to creamy Ageratina altissima ‘Braunlaub’ (main image) and Sanguisorba ‘Cangshan Cranberry’, which are wonderful as pinpricks of brightness held in its suspension. It is easily 1.2 metres tall here and, weighed down by rain, it can splay, and I have found that several are too close to the path, but I like it and will find them a place deeper within the borders.

Panicum virgatum ‘Heiliger Hain’

Panicum virgatum ‘Heiliger Hain’

Panicum virgatum ‘Shenandoah’

Panicum virgatum ‘Shenandoah’

Though it has not done as well for me here – it may well be that it is a selection from a drier part of the States – ‘Heiliger Hain’ has been beautiful. Silvery and fine, the leaf tips colour red early in summer and are strongly blood red by this point in the season. It is small, no more than 80cm tall when in flower, and so I have given it room to rise above Calamintha sylvatica ‘Menthe’ and the delicate Succissella inflexa. Similar in character, though better and stronger, is ‘Shenandoah’ which I have drawn through most of the upper part of the garden. Blue-grey in appearance as it rises up in the first half of summer, it begins to colour in late August, bronze-red becoming copper-orange as it moves into autumn. Neil Lucas of Knoll Gardens says it has the best autumn colour of all panicum. It also stands well in winter to cover for neighbours that have less stamina. Where in the right place, with plenty of light and no competition at the base whilst it is awakening, it is proving to be brilliant and will be the segue from the summer garden, slowly making its presence felt above an undercurrent of asters to finally eclipse everything in a last November burn.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 29 September 2018

I’ve been clearing out the freezer and pantry over the past few weekends to make room for the end of season fruit harvest. Over the course of the winter we get through nearly all of the fruit we freeze – rhubarb, gooseberries, blackcurrants, raspberries, plums, blackberries and apples – but I can guarantee that, each autumn, in the bottom drawer of the freezer there will be a container full of redcurrants, untouched since they were picked.

I really like redcurrants, when in season. Freshly picked off the bush and used to garnish anything from morning granola to a festive summer pavlova, their carmine colouring and jewel-like clarity draw you to them like a magpie. However, I have always found that they produce far too much fruit for their usefulness when fresh, and that their uses when preserved are limited. But, we have a very healthy redcurrant bush and every year it produces as much fruit as before. So, in the past couple of years, I have been trying to find other ways to use the glut.

Redcurrants are very high in pectin but, when cooked, are not strongly flavoured and retain their vibrant colour. So, as well as their ubiquitous use in redcurrant jelly they are very useful in making preserves with fruits that are low in pectin, particularly red ones, such as raspberries, strawberries and rhubarb, as they brighten the colour of the preserve. Since they are high in acid, they also provide a good balance to fruits that can otherwise be too sweet on their own in a jam. Last year I made the most of a good (but still small) harvest of wild strawberries by cooking them briefly in a heavy redcurrant syrup into a jammy compote. The recalcitrant redcurrant acted as a carrier for the delicate, floral flavour of the strawberry, enabling you to fully experience a taste that is usually quite ephemeral. This year I have used the leftover redcurrants with the last of this year’s autumn fruiting raspberries which, after producing for weeks now, are finally running out of steam, and so need stretching out.

Just a small proportion of our annual redcurrant harvest

Just a small proportion of our annual redcurrant harvest

I have always loved raspberry jam. As a child I much preferred it to strawberry, which I found sickly and artificial tasting. However, I have always found the seeds a bit irksome. If it’s possible, redcurrants are even seedier than raspberries, and so a jam made of the two would have proven particularly dentally challenging. And there is something about a pure, clear fruit jelly that I find almost primally enchanting. The distillation of fruit into the essence of that fruit. I generally use less sugar than is used in traditional recipes, where the ratio of fruit to sugar is usually 1 to 1. This is because I prefer a runnier preserve, and also find the reduced sweetness more palatable, and less overwhelming to the flavour of the fruit.

Raspberries and roses are good bedfellows, so when making this batch of jam, I stewed some rose geranium leaves (Pelargonium ‘Attar of Roses’ has the best flavour) in it just before potting up. The rose flavour is taken up by the fruit, but the sharpness of the redcurrants prevents it from being cloying and elevates this preserve into something which is as good on vanilla ice-cream, stirred through a fool or used as the base of a vodka cocktail as it is smeared on a piece of toast or a freshly baked scone. It feels good to eke out these last moments of summer.

Makes 3-4 225g jars

INGREDIENTS

500g raspberries

500g redcurrants

Granulated sugar

4 large rose geranium leaves or 1 teaspoon rose essence

400ml water

METHOD

Put the fruit and water into a preserving pan. Simmer gently for 30 to 40 minutes, until the fruit has completely collapsed and given up all of its juice. Break it up more with a wooden spoon, then pour into a jelly bag or colander lined with muslin and allow the juice to strain into a large bowl for at least 6 hours, preferably overnight. Do not squeeze or press the pulp or the bag or the jelly will be cloudy.

Measure the juice, return it to the cleaned pan and bring slowly to the boil. Measure 450g of sugar for every 600ml of juice and add this to the juice once it is boiling. Stir well to dissolve the sugar, and carefully scrape in any sugar crystals from the side of the pan. Bring back to the boil and then boil hard for 8 to 10 minutes without stirring until the desired setting point is reached.

Remove from the heat, stir to disperse any scum on the surface and then drop the rose geranium leaves – or stir the rose essence – into the hot jam. Allow to settle for 5 minutes, then remove the geranium leaves, stir well and then pot into warm, sterilised jars. Seal immediately and allow to cool before labelling and storing in a cool, dark place. This will keep unopened for up to a year. Once opened keep in the fridge.

Recipe & Photography: Huw Morgan

Published 22 September 2018

When I was a child we spent every summer holiday in Wales, staying with my maternal grandparents who lived near Gowerton, the gateway to the Gower peninsula. When the weather was good we would head straight to Horton beach after breakfast, with crab paste and ham sandwiches wrapped in foil, hard-boiled eggs, bags of crisps and a tin of Nana’s homemade Welsh Cakes and pre-buttered slices of Bara Brith to see us through the day.

My grandfather was a Baptist minister, so on Sundays the day started differently. Nana was up even earlier than usual, housecoat on and getting lunch (or dinner as we called it in those days) prepared before we all headed off to chapel. All of the vegetables came from the back garden, which was given over entirely to food; potatoes, runner beans, peas, broad beans, lettuces, onions, beetroot, carrots, parsnips, swedes, cabbages and, of course, leeks. A tiny greenhouse was full to bursting with tomatoes and cucumbers. At the front of the house, the long bed running down one side of the path was filled with Dadcu’s dahlias, tied to bamboo canes in regimented rows, a cacophony of colour in every shape available, like sweeties. On the other side of the path an assortment of exotics planted into the lawn, including a phormium, a bamboo and a pampas grass, provided me and my brother with a playtime jungle.

The chapel was just on the other side of the street so, as soon as the service was over, Nana would head back to the manse to get dinner on the table for Dadcu’s return. Although a full roast dinner was not unusual on these sweltering summer Sundays, the meal I remember most clearly, and which was my favourite, was cold boiled ham with minted new potatoes and broad beans in parsley sauce. I loved the combination of the cold, salty meat, buttery potatoes and creamy beans and would ensure I got a little of each on every forkful.

Thinking back to this garden now I realise that, although Dad also grew veg in our North London garden, it was Dadcu’s kitchen garden where I first really understood the connection between plant and plate. My brother and I would be sent out to help dig potatoes, getting a rush of excitement as the first pearly tubers were heaved from the rich, dark soil, scrabbling to grab them and put them in the bucket. Pulling carrots straight from the ground I would think of Peter Rabbit, although I was sure that, unlike Mr. McGregor, the Revd. Jones did not have a gun. And often I would sit on the back step with Nana and Mum easing broad beans from their pods, marvelling at their cushioned, fleecy protection and enjoying the plonking noise they made as they fell into a plastic bowl at our feet. I never questioned that what we ate at mealtimes had been grown just yards from the dining table, nor that there was work required to get it there. I think that even then those vegetables tasted better to me because they were so fresh and I had helped get them to table.

Broad Bean ‘Karmazyn’

Broad Bean ‘Karmazyn’

Although I can’t profess to be as good a vegetable gardener as my grandfather, now that we have a kitchen garden of our own, I find it hard to buy anything other than lemons, melons or peaches from the local greengrocer in the summer. The feeling of being able to assemble a meal entirely from vegetables you have grown, harvested and prepared yourself has no equal. People say that vegetable gardening is hard work, and I agree, but I don’t understand why this is seen as a negative. The time, care and nurturing that goes into producing your own food gives you a connection to it that is as nourishing as the food itself. When you understand the hard work involved in growing, tending and harvesting you stop taking food for granted and get some perspective on how much food should really cost.

So, to get back to the broad beans. We have grown two varieties this year. An unnamed heritage variety with very decorative, dark pink flowers and green beans from a late autumn sowing, and a variety named ‘Karmazyn’, with white flowers and beautiful rose pink beans, which were sown in March. Surprisingly, the later sown ‘Karmazyn’ have been the quicker to mature. Earlier in the season, as it became apparent that the plants were starting to overtake their autumn-sown neighbours, I was concerned that we were going to have a major glut when both varieties came together, but it now appears we will have a good succession from pink to the green. Close by the artichokes are producing almost faster than we can eat them. ‘Bere’, the variety we grow, is spiny with little meat at the base of the leaves, but the hearts are a good size, sweet and strongly flavoured.

Due to their synchronised production in the garden it is no surprise that broad beans and artichokes are commonly cooked together, with a variety of recipes to be found in French, Italian, Greek, Turkish and other Middle Eastern cuisines. What is common to many of them is the generous use of lemon and fresh herbs. This recipe is very loosely based on an Elizabeth David recipe for Broad Beans with Egg & Lemon from Summer Cooking, which would appear to be of Greek origin. Here the boiled vegetables are dressed with a light, creamy, herb-flecked sauce. A more refined and delicate version of my dear Nana’s beans, although just as good with a couple of slices of cold, boiled ham.

Artichoke ‘Bere’

Artichoke ‘Bere’

INGREDIENTS

Artichokes, 4 small per person

Broad beans, I kg in their pods to yield about 250g

Zest and juice of 1 lemon (reserve 1 tablespoon of juice for the sauce)

Sauce

Butter, 25g

Garlic, a small clove, minced

Cornflour, 1 teaspoon

The yolk of a small egg, beaten

Single cream, 4 tablespoons

Tarragon or white wine vinegar, 1 teaspoon

Lemon juice, 1 tablespoon

Cooking water from the beans, about 200 ml

Fennel, 1 tablespoon finely chopped

Dill, 1 tablespoon finely chopped

Tarragon, 1 tablespoon finely chopped

Salt

Serves 4

METHOD

Bring a large pan of water to the boil. Cook the artichokes for 15-20 minutes until the point of a sharp knife can be easily inserted into the base. Drain the artichokes, run under a cold tap for a moment and then allow to drain and cool completely.

Put the lemon juice in a small bowl. Cut the stalks from the artichokes and gently remove and discard all of the leaves until you reach the choke. Carefully scrape out the choke with the edge of a teaspoon. Tidy the hearts with a sharp knife removing any tough green bits. Rinse in a bowl of water to remove any clinging choke hairs. Dip each heart into the lemon juice as you go and put to one side in a bowl.

Bring a fresh pan of water to the boil. Throw in the beans and cook until just done. Freshly picked ones take only 2 or 3 minutes, older beans will take a little longer and may need to be slipped from their tough outer skins after cooling. When cooked remove 200ml of the cooking water and keep to one side. Then drain the beans and immediately refresh in cold water. Drain and reserve.

To make the sauce, in a pan large enough to take the artichokes and beans, melt the knob of butter until foaming. Take off the heat, put in the garlic and swirl the pan around to cook it lightly and flavour the butter. Still off the heat put in the cornflour and stir well. Add the cream and stir again. Add the egg yolk and stir once more. Then add about 150ml of the reserved cooking water, the vinegar and lemon juice. Season with salt. Put the pan back on a low heat and stir continuously until the sauce starts to thicken. Taste to ensure the cornflour is well cooked and adjust the seasoning. The sauce should be glossy and the consistency of single cream. If it is too thick loosen with some of the reserved cooking water. Put in the chopped herbs and lemon zest and stir through. Put the artichokes and broad beans into the pan and stir gently but thoroughly to ensure that all of the vegetables are well coated with the sauce.

Transfer to a serving dish, and strew some more herbs and lemon zest over the top. Serve warm or at room temperature.

Good enough to eat simply on its own or on toast, this is also a perfect side dish for poached salmon or trout, and cold roast chicken.

You can use any combination of soft green herbs that you have available. Chervil is particularly good, as are parsley and mint. For a more substantial side dish a couple of handfuls of the tiniest, boiled new potatoes make a fine addition.

Recipe & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 23 June 2018

Although the snow from last weekend has all but gone, the drifts that stubbornly mark the lee of the hedges on the coldest slopes are a reminder that winter’s grip is still apparent. The primroses, however, have a schedule to keep and have responded with gentle defiance. The first flowers were out just days after the first thaw to light the dark bases of the hedgerows, and now they are set to make this first official week of spring their own.

Since arriving here, we have done our best to increase their domain. Although they stud the cool, steep banks of the lanes, they were all but absent on the land where the cattle had grazed them out. Save for the wet bank above the ditch where they were protected from the animals by a tangle of bramble. We noted that they appeared in this inaccessible crease with ragged robin, angelica and meadowsweet. Four years ago we fenced the ditch along its length to separate the grazing to either side and since then have done nothing more than strim the previous season’s growth in early January to keep the brambles at bay.

Primroses (Primula vulgaris) colonise the banks above the ditch

Primroses (Primula vulgaris) colonise the banks above the ditch

The new regime has seen a slow but gentle shift in favour of increased diversity. Though the brambles had protected them in the shade beneath their thorny cages, now that they have been given headroom the primroses have flourished. Their early start sees them coming to life ahead of their neighbours and, by the time they are plunged once more into the shade of summer growth, they have had the advantage. Four years on we can see them increasing. The mother colonies now strong, hearty and big enough to divide and distinct scatterings of younger plants that have taken in fits and starts where the conditions suit them.

Each year, as soon as we see the flowers going over, we have made a point of dividing a number of the strongest plants. It is easy to tease them from their grip in the moist ground with a fork. However, I always put back a division in exactly the same place, figuring they have thrived in this spot and that it is a good one. A hearty clump will yield ten divisions with ease, and we replant them immediately where it feels like they might take. Though they like the summer shade, the best colonies are where they get the early sunshine, so we have followed their lead and found them homes with similar conditions.

The divisions taken from the heavy wet ground of the ditch have been hugely adaptable. The first, now six years old and planted beneath a high, dry, south-facing hedgerow behind the house, have flourished with the summer shade of the hedge and cover of vegetation once the heat gets in the sun. It is my ambition to stud all the hedgerows where we have now fenced them and they have protection from the sheep. Last year’s divisions, fifty plants worked into the base of the hedge above the garden, have all come back despite a dry spring. Their luminosity, pale and bright in the shadows, will be a good opening chorus in the new garden. The tubular flowers can only be pollinated by insects with a long proboscis, so they make good forage for the first bumblebees, moths and butterflies.

The six year old divisions at the base of the south-facing hedge behind the house

The six year old divisions at the base of the south-facing hedge behind the house

A one year old division at the base of the hedge above the garden

A one year old division at the base of the hedge above the garden

By the time the seed ripens in early summer, the primroses are usually buried beneath cow parsley and nettles, so harvesting is all too easily overlooked. However, last year I remembered and made a point of rootling amongst their leaves to find the ripened pods which are typically drawn back to the earth before dispersing. The seed, which is the size of a pinhead and easily managed, was sown immediately into cells of 50:50 loam and sharp grit to ensure good drainage. The trays were put in a shady corner in the nursery area up by the barns and the seedlings were up and germinating within a matter of weeks. As soon as the puckered first leaves gave away their identity, I remembered that it was a pod of primrose seed that had been my first sowing as a child. Though I cannot have been more than five, I can see the seedlings now, in a pool of dirt at the bottom of a yoghurt pot. The excitement and the immediate recognition that, yes, these were definitely primroses, was just as exciting last summer as it was then.

Primrose seedlings

Primrose seedlings

The young plants will be grown on this summer and planted out this coming autumn with the promise of winter rain to help in their establishment. I will make a point of starting a cycle of sowings so that, every year until I feel they are doing it for themselves, we are introducing them to the places they like to call their own. The sunny slopes under the hawthorns in the blossom wood and the steep banks at the back of the house where it is easy to put your nose into their rosettes and breathe in their delicate perfume. I will plant them with violets and through the snowdrops and Tenby daffodils, sure in the knowledge that, whatever the weather, they will loosen the grip of winter.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 24 March 2018

Sandwiched between storms and West Country wet, a miraculous week fell upon the final round of planting. We’d been lucky, with the ground dry enough to work and yet moist enough to settle the final splits from the stock beds. It took two days to lay out the plants and then two more to plant them and the weather held. Still, warm and gentle.

I’ve been planning for this moment for some time. Years in fact, when I consider the plants that I earmarked and brought here from our Peckham garden. They came with the promise and history of a home beyond the holding ground of the stock beds, and now they are finally bedded in with new companions. There are partnerships that I have been long planning for too but, as is the way (and the joy) of setting out a garden for yourself, there are always spontaneous and unplanned for juxtapositions in the moment of placing the plants.

The autumn plant order was roughly half that of the spring delivery, but the layout has taken just as much thought in the planning. I did not have a formal plan in March, just lists of plants zoned into areas and an idea in my head as to the various combinations and moods. It was the same this autumn, but forward thinking was essential for the combinations to come together easily on the day. Numbers for the remaining beds were calculated with about a foot between plants. I then spent August refining my wishlist to edit it back and keep the mood of the garden cohesive. The lower wrap, with its gauzy fray into the landscape, allows me to concentrate an area of greater intensity in the centre of the garden. The top bed that completes the frame to this central area and runs along the grassy walk at the base of the hedge along the lane, was kept deliberately simple to allow the core of the garden its dynamism.

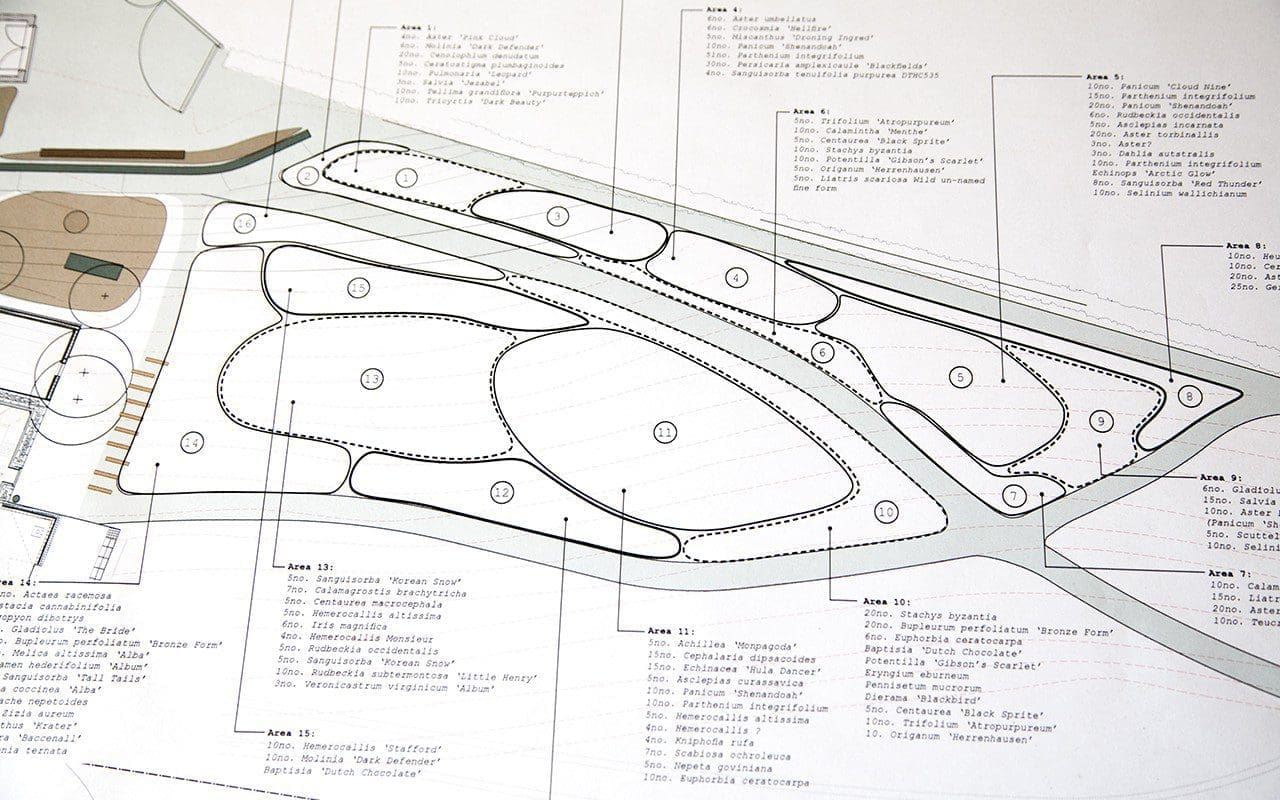

The zoning plan for the central section of the garden

The zoning plan for the central section of the garden

The central path with the top and central beds to either side

The central path with the top and central beds to either side

The top of the central bed

The top of the central bed

The end of the central bed

The end of the central bed

The middle of the top bed

The middle of the top bed

The end of the top bed

The end of the top bed

My autumn list was driven by a desire to bring brighter, more eye-catching colour closer to the buildings, thereby allowing the softer, moodier colour beyond to recede and diminish the feeling of a boundary. The ox-blood red Paeonia delavayi that were moved from the stock beds in the spring and now form a gateway to the garden, were central to the colour choices here. They set the base note for the heat of intense, vibrant reds and deep, hot pinks including Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’, Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’ and Salvia ‘Jezebel’ on the upper reaches. The yolky Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’, lime-green euphorbias and the primrose yellow of Hemerocallis altissima drove the palette in the centre of the garden.

Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’

Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’

Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’

Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’

Salvia ‘Jezebel’

Salvia ‘Jezebel’

Once you have your palette in list form, it is then possible to break it down again into groups of plants that will come together in association. Sometimes the groups have common elements like the Panicum virgatum ‘Shenandoah’, which link the new beds to the ones below them. Although I don’t want the garden to be dominated by grasses, they make a link to the backdrop of the meadows and the ditch. They are also important because they harness the wind which moves up and down the valley, catching this unseen element best. Each variety has its own particular movement; the Molinia caerulea ‘Transparent’, tall and isolated and waving above the rest, registers differently from the moody mass of the ‘Shenandoah’, which run beneath as an undercurrent.

To play up the scale in the top bed, so that you feel dwarfed in the autumn as you walk the grassy path, I have planned for a dramatic, staggered grouping of Panicum virgatum ‘Cloud Nine’. They will help to hold the eye mid-way so the planting is revealed in chapters before and then after. This lofty grass with its blue-grey cast will also separate the red and pink section from the violets and blues that pick up in the lower parts of the walk to link with the planting beyond that was planted in the spring. These dividers, or palette cleansers, are important, for they allow you to stop one mood and start another without it jarring. One combination of plants can pick up and contrast with the next without confusion and allow you to keep the varieties in your plant list up for interest and diversity, without feeling busy.

Each combination within the planting has its own mood or use. Spring-flowering tellima and pulmonaria will drop back to ground-cover after the mulberry comes into leaf and the garden rises up around it. Aster ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’ and Schizostylis coccinea ‘Major’ beneath the Paeonia delavayi for late season colour and interest. The associations that are designed to jump the path from one side to the other in order to bring the plantings together are key to cohesiveness. The sunny side of the path favours the plants in the mix that like exposure, the shady side, those that prefer the cool, and so I have had to be aware of selecting plants that can cope with these differing conditions. Consequently, I have included plants such as Eurybia divaricata that can cope with sun or shade, to bring unity across the beds. The taller groupings, which I want to feel airy in order to create a feeling of space and the opportunity of movement, always have a number of lower plants deep in their midst so that there is room and breathing space beneath. Sometimes these are plants from the edge plantings such as Calamintha sylvatica ‘Menthe’, or a simple drift of Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield’, which sweeps through the tall tabletop asters (Aster umbellatus). This undercurrent of the adaptable persicaria, happy in sun or shade, maintains a fluidity and movement in the planting.

Stock plants of Panicum virgatum ‘Cloud Nine’

Stock plants of Panicum virgatum ‘Cloud Nine’

Schizostylis coccinea ‘Major’

Schizostylis coccinea ‘Major’

Aster umbellatus and Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield’

Aster umbellatus and Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield’

Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’

Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’

The combinations, sixteen in total, were then focused by zoning them on a plan. The plan allowed me to group the plants by zone in the correct numbers along the paths for ease of placement. Marking out key accent plants like the Panicum ‘Cloud Nine’, Glycyrrhiza yunnanensis, Hemerocallis altissima and the kniphofia were the first step in the laying out process. Once the emergent plants were placed, I follow through with the mid-level plants that will pull the spaces together. The grasses, for instance, and in the central bed a mass of Euphorbia ceratocarpa. This is a brilliant semi-shrubby euphorbia that will provide an acid-green hum in the centre of the garden and an open cage of growth within which I can suspend colour. The luminous pillar-box red of Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’ and starry, white Dahlia merckii ‘Alba’. Short-lived Digitalis ferruginea were added last to create a level change with their rust-brown spires. However, I am under no illusion that they will stay where I have put them. Digitalis have a way of finding their own place, which isn’t always where you want them and, when they re-seed, I fully expect them to make their way to the edges, or even into the gravel of the paths.

Euphorbia ceratocarpa

Euphorbia ceratocarpa

Dahlia merckii ‘Alba’

Dahlia merckii ‘Alba’

Hemerocallis altissima

Hemerocallis altissima

Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’

Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’

Over the summer, I have been producing my own plants from seed and it has been good to feel uninhibited with a couple of hundred Bupleurum longifolium ‘Bronze Form’ at my disposal to plug any gaps that the more calculated plans didn’t account for. Though I am careful not to introduce plants that will self-seed and become a problem on our hearty soil, a few well-chosen colonisers are always welcome for they ensure that the garden evolves and develops its own balance. I’ve also raised Aquilegia longissima and the dark-flowered Aquilegia atrata in number to give the new planting a lived-in feeling in its first year. Aquilegia downy mildew is now a serious problem, but by growing from seed I hope to avoid an accidental introduction from nursery-grown stock. The columbines are drifted to either side of the path through the blood-red tree peonies and my own seed-raised Hesperis matronalis var. albiflora. For now they will provide me with an early fix. Something to kick-start the new planting and then to find their own place as the garden acquires its balance.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 28 October 2017

Planting the fruit orchard was one of our first major projects the winter we arrived here. I knew where I wanted to see it almost immediately, on the south-facing slopes beyond the barns to the west. Nestled into the hill, it was to continue the spine of productivity that runs along this contour. House, vegetable garden, barns, compost heaps and then orchard. It had a rhythm to it that felt comfortable.

Later, and after it was planted, neighbours told us that there had once been fruit trees growing on the same slopes, so it was right to have made the move so quickly. I’d been wanting to plant an orchard for myself for years and made my lists with relish, choosing West Country apples, both cookers and eaters, and a number of pears and plums. I paced out the planting stations in an offset grid with 8 metres between the trees. Doing it by eye meant that it went with the slope and the grid took on a more informal feeling that was less rigid.

The Plum Orchard

The Plum Orchard

Thirteen apples were set on their own on the lower slope, whilst five pears and then the plums sat above them. In making the decision as to how the orchard should step across the slope, I noted how the frost settled and where the cold air drained as it pooled lower in the hollow. The pears, which like a warm, sheltered position, were planted up close to the barns in the lea provided by the hedge and the buildings. The later-flowering apples were placed lower down the slope in the hope that the frosts, which tend to hang low, were mostly over by the time they were in blossom. The early-to-flower plum orchard was put on the highest ground that linked to the blossom wood in the next field above, as they also prefer a warm, free-draining position. Here they have so far escaped the frosts. To date, for there is still always time to learn, I am happy to have gone with my intuition.

The plum orchard is a loose term for the collection of a dozen or so trees that now inhabit this top corner of the field. I say loose because they all have different characteristics that are driven by the original species from which they have been selected, or from the cross between the edible species. So, to explain, the plum orchard includes true plums, mirabelle plums, damson plums and greengages. We also have two bullace, an old term for a wild plum. Three yellow ones, given to us by a local farmer who has them growing in the hedgerows above our land, are planted in the hedge between the plum orchard and the blossom wood. They may be ‘Shepherd’s Bullace’ or ‘Yellow Apricot Bullace’, two old named varieties that were once very commonly grown. These make a link to an ancient, gnarled tree by the barns, which is dark violet and eats like a damson. The cherry plums (Prunus cerasifera) sit in the blossom wood itself.

Yellow bullace

Yellow bullace

The old black bullace by the barns

The old black bullace by the barns

First to flower, and indeed to fruit, are the cherry plums, which are good both for February blossom and jam making. Their flavour reminds me of the perfumed Japanese ume plums and we have in the past made a delicious plum brandy from them. In the orchard it is the mirabelle plums (first recommended to me by Nigel Slater, who grows them at the end of his garden) that are the first to flower and fruit. Originally from Eastern Europe, but grown to perfection in France, this is a small plum, usually with a tart flavour. Generally preferred for cooking, ‘Mirabelle de Nancy’ has marble sized, apricot-coloured fruit which are fragrant and sweet enough to eat off the tree if picked just before they drop. ‘Gypsy’, with larger red fruit, is a cooker and the earliest of them all, ripe almost a month ago. If I were to lose one, it would be ‘Golden Sphere’, whose flavour is bland in comparison, but it is a pretty plum, well-named for its colour.

Cherry plums

Cherry plums

Mirabelle de Nancy

Mirabelle de Nancy

If I were only able to have one plum tree, it would be a greengage. As a rule, the yellow plums are said to have better flavour than the reds, but greengages are the most aromatic and, in our opinion, the most delicious. Of course, there is a small price to pay for such a delicacy, as greengages have a reputation for being shy to fruit. I have five in the orchard. ‘Early Transparent’ is the most reliable and has fruited plentifully. ‘Denniston’s Superb’ fruited well this year too and has the very best flavour. Despite the skins being less than perfect, the greengage perfume and the depth of flavour of this greengage is superlative – as refined and floral as a good ‘Doyenne de Comice’ pear or, if you were living in heat, a freshly picked white peach. I have three more greengages that are yet to prove themselves; ‘Reine Claude de Bavay’, which is famously shy to fruit, ‘Bryanston Gage’ and ‘Cambridge Gage’, which the sheep have managed to reach, pulled at and damaged, so I am waiting patiently for results next year.

Gage ‘Early Transparent’

Gage ‘Early Transparent’

We have two true plums in the orchard. ‘Victoria (Willis Clone)’, a selection that is reputedly free of silverleaf, an airborne bacteria to which ‘Victoria’ is prone and which can infect broken branches in the summer. Plums, particularly the heavy fruited ‘Victoria’, are famous for snapping under the weight of their fruit, so I have taken to gently shaking the tree a little earlier in summer to lighten the load that the June Drop hasn’t done for. Though the ‘Victoria’ is a good looking plum – it is next to ripen after the greengages – it is nice but rather ordinary. It is, however, indispensable for freezing for winter crumbles. ‘Warwickshire Drooper’, a vigorous and amber-fruited plum, is better I think. Adaptable for being both an eater and a cooker, and not a plum you can buy off the shelf like ‘Victoria’. It is also a very heavy cropper and makes delicious jam.

Plum ‘Victoria (Willis Clone)’

Plum ‘Victoria (Willis Clone)’

Plum ‘Warwickshire Drooper’

Plum ‘Warwickshire Drooper’

The damsons are perhaps the most beautiful, hanging dark and mysterious, with a violet-grey bloom that, when you reach out and brush the surface, reveals the depth of colour beneath. These are the last to fruit and this year I fear we will miss them in the fortnight we go away on holiday in early September. ‘Shropshire Prune’ (main image) has proven itself to be one of the most reliable fruiters with small, perfumed fruit that are firm and make the strongest flavoured jam. A little earlier and larger of fruit, ‘Merryweather’ also has very good flavour and is one of the only damsons sweet enough to eat from the tree if left to fully ripen.

Damson ‘Merryweather’

Damson ‘Merryweather’

The plums are something you have to watch as they ripen, for they take some time to ready but, when they do, they all ripen over the space of a fortnight. The range of varieties in the plum orchard helps here in staggering the harvest, but getting to them before the wasps do is always a challenge. This year, however, we are bombarded with fruit which means there is plenty to go round, and I have been heartened to see that the rotting fruit also provides a late summer larder for honeybees and butterflies. I have a long, three-legged ladder with an adjustable third leg ideal for picking on our slopes but, for expediency, it has been quicker to lay down tarps on the hummocky grass and gently shake the trees. The fruit cascades around you and you can pluck the best without reaching into the branches to be stung by the competition.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 26 August 2017

The meadows that were cut for hay in the middle of July are already green and lush after the August rains. The hay needs to be cut before the goodness goes out of it, but we leave it until the yellow rattle rattles in its seedpods and has dropped enough seed for next year. With the cut go a host of summer wildflowers which have already set seed. Those that mature later are lost with the cut. So in the fields that are put to grazing when the grass regenerates after the hay cut, we will not see the scabious or the knapweeds. If they are present at all, they will not get the chance to seed and, if we were to have orchids, (one day, hopefully) their cycle would also be curtailed as they are only now ripening.

Where the land is too steep for the tractor, we find ourselves with rougher ground and other habitats. The steep slopes dipping away and down from The Tump are left uncut and, with the sheep shaping their ecology, they have become tussocked and home to a host of wildlife that has made this protected place home. The marsh thistle likes it there and can compete, and slowly we are seeing the first signs of woodland, with hawthorn and ash sheltering in the creep of bramble. We will have to make a decision as to where we apply a hand in preventing the woody growth from encroaching upon the grassland, as all the habitats have their merit.

The lower slopes of the Tump above the ditch where the meadowsweet grows are colonised by marsh thistle

The lower slopes of the Tump above the ditch where the meadowsweet grows are colonised by marsh thistle

Marsh Thistle (Cirsium palustre)

Marsh Thistle (Cirsium palustre)

The field that climbs steeply immediately behind the house is raked off by hand after the farmer mows it for us. It is too steep to bale so it is cut late to allow an August flush of meadow life. It is a task raking the cuttings to keep the fertility down, but one that is getting easier each year with concerted efforts to colonise the grass with the semi-parasitic rattle. This field and the newly seeded banks that sweep up to the house are valuable for being late and, as I write on a breezy bright day in a wet August, it is alive with the latecomers and the host of wildlife that retreats to find sanctuary there.

The ‘between places’ that are formed by banks that are just too steep to manage occur along the contours and below the hedges that run along them. The precipitous slope (main image) between our two top fields (The Tynings) has been something of a revelation and, seven summers in, we are seeing the rewards of making an effort with its management. A neighbour told us that every twenty years or so the farmer before us would fell the ash seedlings that took the banks as their domain. This must have last happened five or six years before we arrived and, although it was then covered in young ash and bramble, it was clear that this south-facing slope had the potential to be more than just scrub, and provide a contrast to the grazed meadows. The second winter we were here, we cleared the bramble, cutting off great mats and rolling them down to the bottom of the slope like thorny fleeces.

The Tynings bank in April with cowslips showing

The Tynings bank in April with cowslips showing

That spring the newly exposed ground immediately gave way to cowslips and violets that had been sheltering amongst the brambles. In the summer they were followed by smatterings of wild marjoram, field scabious, common St. John’s Wort, crow garlic, hedge bedstraw and agrimony, indicating the limey ground and the south-facing position.

Why the field levels vary so dramatically to either side of the contour-running hedge is intriguing. The ground in the valley is prone to slipping and the twenty-foot slope between these two fields suggests the occurrence of something of that nature in the past. The steepness of the bank and the shale and the clay that has been exposed in the underlying strata make it incredibly free-draining and the plants that have colonised here are specific and a contrast to those found on flatter ground. If you walk along the bank on a hot day now it is full of marjoram and you can hear it hum with life and crack and pop as vetch pods scatter their seed.

Field Scabious (Knautia arvensis) and Wild Marjoram (Origanum vulgare)

Field Scabious (Knautia arvensis) and Wild Marjoram (Origanum vulgare)

Agrimony (Agrimonia eupatoria)

Agrimony (Agrimonia eupatoria)

Common Knapweed (Centaurea nigra)

Common Knapweed (Centaurea nigra)

We have given the bank a ‘year on, year off’ cut, strimming in the depths of winter when the thatch is at its least resistant. All the cuttings are roughly raked to the bottom of the slope (and then burned) so that there is plenty of light and air for regeneration. We leave the spindle bushes, the wild rose and a handful of ash seedlings, but the sycamore seedlings that proliferate from the large trees in the hedgerow are cut to the base to keep them from getting away. After three cuts over six years the bank is now thick with marjoram and scabious, hedge bedstraw, common and greater knapweeds and this year, wild carrot, one of my favourite umbellifers for late summer. It is abuzz with honeybees, bumblebees, hoverflies and butterflies.

This bank has been the inspiration for the newly-seeded slopes around the house and last year I gathered seed from here to grow on as plugs to bulk up the St. Catherine’s seed mix that went down last September. The seed is sown fresh, as soon as it is gathered, into cells and left in a shady place for a year. I have not thinned the seedlings and have deliberately grown them tough so that they are able to cope with the competition. Last year’s batch was planted out not long after the banks were sown to add early interest, and some are visible and flowering already.

Crow garlic (Allium vineale)

Crow garlic (Allium vineale)

Greater Knapweed (Centaurea scabiosa)

Greater Knapweed (Centaurea scabiosa)

Common St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum)

Common St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum)

Hedge Bedstraw (Galium album)

Hedge Bedstraw (Galium album)

This year’s plugs, which are destined for the late meadow behind the house, will be put out in September, straight after the banks have been cut. We have already seen a difference in the wildlife since creating these wilder spaces up close to the buildings, with more swallows than before swooping low for insects, the increased presence of a pair of breeding kestrels, a red kite that formerly kept itself to the farther end of the valley, more bats and, a couple of weeks ago, an exciting moment when a barn owl came sweeping low over the banks as dusk fell. Every year, with careful management, we will see a successive layer of change, and one year in the not too distant future, a sure but certain enrichment.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 12 August 2017

The new planting went in on the spring equinox, a week that saw the energy in the young plants shifting. Just seven days later the emerging fans of the hemerocallis were already splayed and flushed, and the signs were also there in the tightly-clasped crowns of the sanguisorba. The chosen few from my trial in the stock beds had to be split to make up the numbers I needed, but energy was on their side and, once in their new home, they seized life quickly to push new foliage.

We mulched the beds immediately after planting to keep the ground clean and to hold in the moisture whist the plants were establishing. Mulching saves so much time in weeding whilst a garden is young and there is more soil than knit of growth. This year I was also thankful because we went into five long weeks without rain. I watered just once, so that the roots would travel down in search of water, but once only so that they did not become reliant. The mulch held this moisture in the ground and the contrast to the old stock beds that went without has been is remarkable. Spring divisions that went without mulch have put on half as much growth and have needed twice as much water to get the same purchase. I can see the rigour of my Wisley training in this last paragraph, but good habits die as hard as bad ones.

14 May 2017

14 May 2017

17 June 2017

17 June 2017

Since it rained three weeks ago, the growth has burgeoned. As the summer solstice approaches the dots of newly planted green that initially hugged the contours of our slopes have become three dimensional as they have reared up and away into early summer. I have been keeping close vigil as the new bedfellows have begun to show their form, noting the new combinations and rhythms in the planting. Information that I’d had to hold in my head while laying out the hundreds of dormant plants and which, to my relief, is beginning to play out as I’d imagined.

14 May 2017

14 May 2017

16 June 2017

16 June 2017

Of course, there are gaps where I am waiting for plants that were not then available, and also where there were gaps in my thinking. There are combinations that I can see need another layer of interest, and places where the plants are already showing me where they prefer to be. The same plant thriving in the dip of a hollow, but not on a rise, or vice versa. Plants have a way of letting you know pretty quickly what they like. At the moment I am just observing and not reacting immediately because, as soon as the foliage touches, the community will begin to work as one, creating its own microclimate that will in turn provide influence and shelter. I lost my whole batch of Milium effusum ‘Aureum’, which I put down to the exposure on our south-facing slopes. However, most of them have managed to set seed, so I am hoping that next spring the seedlings will find their favoured positions to thrive in the shade of larger, more established perennials.

The wrap of weed-suppressing symphytum that I planted along the boundary fence is already knitting together, and I’m happy to have this buffer of evergreen foliage to help prevent the landscape from seeding in. However, a flotilla of dandelion seed sailed over the defence and are now germinating in the mulch. We saw them parachuting past one dry, breezy day in April as if seeking out this perfect seedbed. They are easy to weed before they get their taproot down and will be less of a problem this time next year when there will be the shade of foliage, but they will be a devil if they seed into the crowns of plants before they are established. A community of cover is what I am aiming for, so that the garden starts to work with me, and time spent protecting it now is time well spent.

Salvia pratensis ‘Indigo’, Nepeta subsessilis ‘Washfield’, Viola cornuta ‘Alba’ & Knautia macedonica

Salvia pratensis ‘Indigo’, Nepeta subsessilis ‘Washfield’, Viola cornuta ‘Alba’ & Knautia macedonica

The comfrey is planted in three drifts. Symphytum grandiflorum, S. ‘Hidcote Blue’ and S. g. ‘Sky Blue Pink’. The latter is new to me and I’m watching carefully that they aren’t too vigorous. I’ll have to keep an eye on the next ripple of plants that are feathered into the comfrey from deeper into the garden as the symphytum can also be an aggressive companion. The Sanguisorba hakusanensis should be able to hold their own, as they form a lush mound of foliage, and the Epilobium angustifolium ‘Album’ should be fine, punching through to take their own space. I’ll clear the young runners where the creep of the comfrey meets the gentler anemone and veronicastrum.

The ascendant plants were placed first when laying out and will form a skyline of towers through which the other layers wander. They are already standing tall and providing the planting with a sense of depth. Thalictrum ‘Elin’ is my height already, a smoky presence of foliage and stems picking up the grey in the young Rosa glauca and proving, so far, to not need staking. This is important, because our windy hillside provides its challenges on this front. Thalictrum aquilegifolium ‘Black Stockings’ has also provided immediate impact, its limbs inky dark and the mauve of the flowers giving early colour and contrast to the clear, clean blue of the Iris sibirica ‘Papillon’. Next year the garden will have knitted together so that the contrasts will work against foliage or each other, but for now the eye naturally focuses not on the gappiness, but where things are beginning to show promise.

Iris sibirica ‘Papillon’

Iris sibirica ‘Papillon’

Thalictrum aquilegifolium ‘Black Stockings’ with Iris sibirica ‘Papillon’ behind

Thalictrum aquilegifolium ‘Black Stockings’ with Iris sibirica ‘Papillon’ behind

There have been a couple of surprises already, with a fortuitous mix up at the nursery reavealing a new combination I had not planned for with a drift of Salvia pratensis ‘Indigo’ coming up as S. nemorosa ‘Amethyst’. I am very particular about my choices and I’d planned for ‘Indigo’ since growing it in the stockbeds, but the unexpected arrival of ‘Amethyst’ has, after my initial perplexity, been a delight. I’ve not grown it before, and I like its earliness in the planting and how it contrasts with the clear blue of the Iris sibirica with a little friction that makes the eye react more definitely than with the blue of ‘Indigo’. I like a little contrast to keep zest in a planting. The Euphorbia cornigera, with their acid green flowering bracts, are also great for this reason with the first magenta of the Geranium psilostemon.

Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’ and Salvia pratensis ‘Indigo’

Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’ and Salvia pratensis ‘Indigo’

Thalictrum rochebrunianum with Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’ behind

Thalictrum rochebrunianum with Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’ behind

As the last few plants that weren’t ready in the nursery become available, I’m wading back into the beds again to find the markers I left there when setting out so that I can trace my original thinking. I am pleased to have done this, because it is very easy to start to reshuffle, but the original thinking is where cohesiveness is to be found. Changes will come later, after I’ve had a summer to observe and see where the planting is lacking or needing another seasonal lift. I can already see the original perennial angelica has doubled in diameter, and I’ve added eight new seedlings which, if left, will be far too many so a few removals will be necessary comer the autumn. Patience will be the making of this coming growing season, followed by action once I can see my plans emerging.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 17 June 2017