This year our pride and joy (as well as provider of steep learning curve) has been the polytunnel. As soon as we decamped to Somerset before lockdown in mid-March, we started to discuss the pros and cons of finally biting the bullet and getting one, which we have discussed at length and then shelved on several occasions. The reason to defer was always the same. We weren’t here enough and, once a polytunnel is up and running, it simply can’t be left for days untended. Suddenly we were compelled to be at Hillside for the foreseeable future and, with the thought of more complete vegetable self-sufficiency firmly in the forefront of our minds, we decided to take the plunge.

Our dreams of a cornucopia of tomatoes, peppers, aubergines, chillis, cucumbers and melons haven’t been fully realised due to a shortage of seed and plug plants immediately after lockdown, and the fact that the polytunnel couldn’t be delivered until the end of May. So our initial plan for a tomato trial with three plants of ten varieties quickly increased to twelve plants of each and so this year, although we have three chilli varieties and two of cucumber, the polytunnel has been pretty much dominated by them. I will write at more length about the polytunnel at a later date, once I have some more experience under my belt, but suffice to say that growing tomatoes in grow bags has this year taught me the importance of a regular watering regimen, the effects of lack of ventilation and the dangers of not starting to apply tomato feed early or regularly enough. We lost almost all the second trusses and, due to the cool August, the third and fourth trusses are only now just starting to ripen. Everyone will be getting Green Tomato Chutney for Christmas this year.

Apart from firm favourites ‘Sungold’ and ‘Gardener’s Delight’ I was keen to trial some plum tomatoes and chose the best known and most reliable varieties, ‘San Marzano’ and ‘Roma’. These are the varieties that are almost invariably in any tin of tomatoes you might buy at the shops. They were surprisingly productive at first and the mini-glut in early August produced ten large jars of bottled whole and chopped tomatoes, as well as several litres of passata and ketchup. Although ripening is definitely slowing down now, somewhat surprisingly it is still the plum tomatoes that are providing the largest usable harvests. This I don’t mind, since I cook with tomatoes pretty often in winter and the idea of being able to use my own preserved ones and not shop-bought is very appealing.

Despite their productivity only the best plum tomatoes are good enough for bottling, so there are always plenty left over. These end up as passata or a simple tomato sauce (which I either bottle or freeze depending on available storage space) and in ketchups, salsas and chutneys. Quite often, however, they end up in our dinner and one of my daily challenges of recent weeks has been ‘What can you make with any combination of courgettes, tomatoes and runner beans ?’. After many nights of making things up as I went along I have started to run out of inspiration and so this week there has been much rifling of recipe books.

I very seldom present another cook’s recipes here, although my own are often tweaked and altered versions of dishes I have eaten or cooked from recipes in the past. However, when I came across this yesterday, it jumped out at me for the intriguing use of two of my main available ingredients in a previously completely unimagined form. What is in effect a tomato and bean pie is elevated in this recipe into a memorable dish of unctuous and exotic richness. Given the apparent humility of the primary ingredients I was unprepared for quite how delicious it is and feel that it is only right to share the original, untweaked, recipe with full credit to Maria Elia from whose excellent book of modern Greek cuisine, Smashing Plates, it is taken. As she says (and as I did myself) it is best to make the filling the day before you plan to assemble it so that the flavours can come together overnight. Of course, not everyone has access to vine-ripened plum tomatoes, so I weighed mine and they came to around 600 grams, equivalent to around two cans drained of their juice.

To balance the richness this would be good served with something fresh and bright such as a citrussy Greek cabbage and carrot coleslaw or a raw fennel, chicory, orange and watercress salad.

Serves 6-8 as a main, 8-12 as a small plate

100 ml olive oil

2 Spanish onions, halved and finely sliced

2 garlic cloves, finely chopped

2 tsp ground cinnamon

5 tbsp tomato purée

10 vine-ripened plum tomatoes, skinned and roughly chopped

500 g runner beans, stringed and cut into 4cm lengths

A pinch of sugar

1 bunch of dill (approx. 30 g), finely chopped, or 2 tbsp dried

1 packet of filo pastry (9 sheets)

100 g melted butter

100 g Medjool dates, stoned and finely sliced

250 g feta, crumbled

6 tbsp clear honey

Sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

Heat the olive oil in a large, heavy-based pan over a low heat and sauté the onion until softened and sticky; this can take up to 20 minutes. Add the garlic, cinnamon and tomato purée and cook for a further 2 minutes. Add the tomatoes and their juices and cook over a medium heat for about 8 minutes, before adding the runner beans, sugar, dill, a pinch of sea salt and 150ml water.

Reduce the heat to a simmer, cover and cook the beans for about 40 minutes, stirring occasionally, until the beans are soft and the sauce is nice and thick. Check the seasoning and cool before assembling.

Preheat the oven to 180°C/gas mark 4. Unfold the pastry and cover with a damp cloth to prevent it from drying out. Brush a baking tray (approximately 30 x 20cm) with melted butter. Line the tin with a sheet of filo (cut to fit if too big), brush with butter and repeat until you have a three-layer thickness.

Spread half the tomato and bean mixture over the pastry, top with half each of the dates and feta. Sandwich another three layers of filo together with melted butter and place on top. Top with the remaining tomato mixture, dates and feta. Sandwich the remaining three filo sheets together as before and place on top.

Lightly score the top, cutting into diamonds. Brush with the remaining butter and splash with a little water. Cook for 35 – 45 minutes or until golden. Leave to cool slightly before serving, drizzling each portion with a little honey.

Words & photographs: Huw Morgan | Recipe: Maria Elia

Published 12 September 2020

Autumn came early this year and before the month of August was out. Refusing to go inside until bed time, we’ve been huddled in blankets, wondering if it is also too cold for the courgettes to throw one last crop and whether the tomatoes in the polytunnel will be more green than red now the evenings are shortening.

We have taken two weeks off to harvest. The last of August and this first week of the golden month. Timed perfectly to not miss the plums that escaped our late spring frosts, as those that did set fruit have been plentiful. ‘Warwickshire Drooper’, appropriately weighting the branches and a fine crop of damsons. Inky ‘Merryweather’ and ‘Shropshire Prune’, the smaller and ‘wilder’ of the two. The pears decided to drop in sequence, one fruit first, to warn you of the coming deluge and then suddenly, everything all on the ground. Get there on the day after the scout that fell and a quarter turn will yield the ripe ones the day before they drop and bruise. ‘Beth’ with her must-eat-immediately creaminess comes first and then ‘Williams’. Firm and then, when just perfect, melting. Countless numbers from the espaliers and fortunately a pause now before ‘Beurre Hardy’ and then a longer wait for the October ‘Doyenne du Comice’, the finest of all and the grand finale here.

The kitchen garden is now in its fifth summer and we have an embarrassment of riches. What to do with such plenty ? In times gone by we would have pulled together to bring in the fruits of the growing season, but in this unusual year, we are missing the many hands and accompanying banter of sharing this time picking and the community effort of preparing and preserving.

To stop and put aside the feeling of guilt that some of your efforts will inevitably go to waste is part of letting the autumn happen. Nothing really does get squandered and we have learned to step back at a certain point and try to take things in. The surfeit of pears and apples that lie strewn in the grass will not have time to moulder before the birds and the critters have them. You need to make time to take these moments in.

This is what this week’s mantlepiece is about. The beginnings of a winding down that will surely leave the growing season behind. Slowed, but far from static, the garden has plenty yet to give. Tagetes and morning glories arguably better than ever in the soft days. There are the autumn performers too, the flowers that are here to complement the senescence. Dahlias and cyclamen, schizostylis and amaranthus designed for now and making September their own. The last push of roses and a final flurry of clematis, surrounded already with a gathering backdrop of silken seed and the rewards of a growing season coming to a close.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 5 September 2020

Burnished coppery

Illuminating darkness

Mother memory

Words and photograph | Huw Morgan

Published 23 November 2019

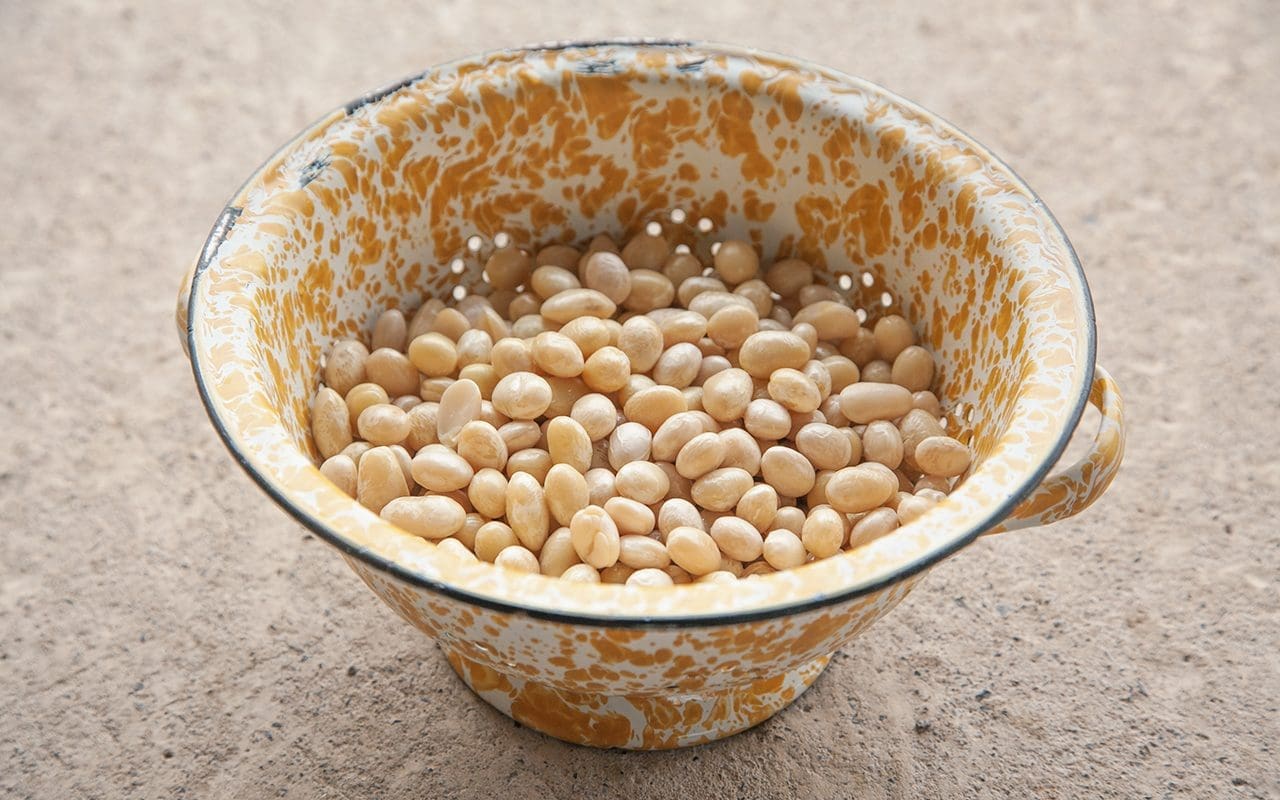

Yesterday we had our first snow. Just the briefest flurry, and it was too wet and warm for it to settle, but snow all the same. The colder weather demands something warm and hearty in the stomach and has finally given me the opportunity to make a long-planned silky soup from the coco beans that have been in the freezer since I harvested them over a month ago.

To date we have only ever grown climbing beans to eat fresh, but this year we grew a range of new beans, some of which I selected specifically for storing. At the end of the summer the bean which had cropped most heavily was ‘Coco Sophie’, a late 18th century variety which became commercially unavailable in 2006, and has only recently been re-introduced by The Real Seed Company. Due to the variety and quality of their seed, it has fast become our go-to seed supplier.

Coco beans are an old French large haricot type, producing shiny, round, creamy white beans with a texture comparable to normal haricot or cannellini beans. However, they are smoother and richer than either. The Coco de Paimpol, which is grown only in Brittany, has its own appelation d’origine contrôlée due to its incomparable texture and flavour. Although I had eaten coco beans in restaurants before and been struck by their silky texture, I had not, until this year, been able to find seed to grow them myself.

I picked the beans when semi-dry – which cuts down their cooking time significantly – and froze them immediately. However, they can be fully dried and then soaked before cooking. If using dried beans for this recipe 400g of dried beans will give a soaked weight of approximately 800g and, although you do not need to sieve the soup, it produces a superior result that is worth the little additional effort.

In my mind I had a velvety smooth, garlic-laden puree flavoured with woody herbs and a whiff of truffle. I had a recollection of having eaten something similar many years ago in Milan, as I associate it with distinct memories of risotto alla milanese, osso buco and whole pan-fried porcini.

A whole bulb of garlic may seem too much initially, but since it is simmered in the stock its strength is tempered and sweetened. The seasonal combination of sage and bay is warm and aromatic. Although we have several types of sage growing here, the most robust and best-flavoured variety is known simply as ‘Italian’, with large silver-grey leaves that are winter hardy and perfect for frying.

Serves 6

3 large leeks, white and pale green parts only, about 250g

3 tbsp olive oil

800g fresh or cooked white beans

1 bulb garlic

2 large sprigs of sage

1 large bay leaf

1.5 litres water or vegetable stock

Freshly grated nutmeg

Salt

Ground white pepper

12 large sage leaves

3 tbsp olive oil

Truffle oil

Heat the olive oil in a large pan over a low heat. Wash, peel and trim the leeks and slice them finely. Put them into the pan, put the lid on and sweat over a low heat for 10 to 15 minutes until translucent. Stir occasionally.

Peel and trim the garlic cloves and leave whole. When the leeks are cooked add the garlic, beans, sage, bay leaf and grated nutmeg to the pan with the water or stock. Bring to the boil and then reduce to a simmer. Cook with the lid on until the beans are soft; about 20 minutes if fresh, or 40 if dried and soaked.

When the beans are done remove the sage and bay leaves, then liquidise the beans and their cooking liquid with a stick blender until smooth. Then, if you want the silkiest smooth soup, push the puree through a fine sieve with the back of a metal spoon. Season with salt and pepper to taste.

In a small frying pan heat the second lot of olive oil. When smoking, fry the sage leaves in batches for about 10 seconds until crisp and just beginning to brown. Remove from the oil onto a piece of kitchen paper.

Ladle the soup into warm bowls. Drizzle over a little truffle oil and garnish each bowl with two fried sage leaves.

Recipe & Photographs | Huw Morgan

Published 16 November 2019

Huw Morgan | 31 October 2019

It is almost three months since Flora first came to Hillside to work with material taken from the garden here. That summer visit was an introductory and learning experience for us both. Flora’s first time in the garden here, time needed to get to know the garden, time to find a setting to shoot in, the challenges of working outside and to be photographed in process when she is usually unseen, off stage. For me there was the self-imposed pressure to do Flora’s art justice in my photographs and to capture those moments of consideration, reflection, decisiveness, choice, care, which I was witness to as she worked.

As she worked this time I started to notice the ways in which Flora relates physically to the space in which the flower arrangement was being made. Standing with her back to me I could tell that she was judging, evaluating, balancing, deciding, framing, all of which could be read from the set of her jaw or the angle of a shoulder. The delicacy with which she would select a stem, find a location for it, and then gently and firmly aid and guide it into position. The final stroking of the plant to allow it to fall naturally and also the sensual pleasure of engaging with plants this intimately.

It reminded me of something Midori, the head gardener at Tokachi Millennium Forest said to us when she was staying here early last autumn, which is that the last flower arrangements of the year should be relished as they are the last opportunity for ‘touching green’ before the winter comes.

Flora Starkey | 1 November 2019

The last time I came to Hillside, Summer was making way for Autumn. This visit Autumn is peaking and the gardens are more subdued, but no less splendid.

We decided to shoot in the same location as before, in front of the beautifully rusted corrugated iron barn. I’m interested to see how the four images will sit together by the end of the year and like the idea of them being in the same place.

As before, we cut sparingly – no more than a few stems from each plant. This time I chose a lot of dried structure – dill, red orache, fluffy willow herb and a stem of Thalictrum ‘White Splendide’ with its delicate mottled yellow leaves. And of course, some essential autumnal colour in the form of Euphorbia cornigera and a snipping from the fiery Prunus x yedoensis.

Moving back to the barn, we pick some blue glass jars from the house & get to work. The space will always dictate the arrangement in terms of scale and the zinc table outside calls for size, not least because of the October wind.

The tall dried pieces were placed first creating the framework, a beautiful Aster umbellatus towering over the others. A few leaves of royal fern quickly followed, adding a myriad of colours in each stem. I carried on building the colour with warm tones before offsetting with the deep blues and violets of a few varieties of salvia.

Even though the stems keep get buffeted by the wind and moving around, I like this way of working. It’s spontaneous & can’t be too precious. After a while, I feel like we’re missing some pops of brighter colour and go foraging for rosehips, finding some spindleberry on the way.

As these are more structural branches, I end up taking the arrangement apart & starting again, adding these elements earlier. Some of the salvia had also started to wilt by the time we got back so we cut a little more. If I were to use this again, I’d try & sear it to make it last longer. I finish with a curling tail of yellow amsonia, a shock of pale yellow scabious and some shiny black berries of wild privet.

As well as wanting to represent the garden in all her autumnal glory, I was also keen to make a smaller and simpler arrangement – something quieter that allows the stems their space to shine. It’s probably how I’m happiest working.

The picture window outside the milking barn provides the setting and frames the vases with the changing landscape behind. I start with a length of old man’s beard and some more euphorbia. A few stems of panicum & chasmanthium add height along with a speckled toad lily. A sprinkling of dainty white asters were added lower down and some oxblood red leaves of fagopyrum trail off to the side, slightly broken but more beautiful for it.

Back in the garden & you can see the silhouettes of winter beginning to appear. Huw & I spent a little time looking at the plants that we’d like to dry and preserve for our next shoot. I’m looking forward to the change of the season already

Anethum graveolens

Aster umbellatus

Astilbe rivularis

Atriplex hortensis

Cercidiphyllum japonicum

Chamaenerion angustifolium ‘Album’

Chasmanthium latifolium

Euonymus europaeus

Euphorbia cornigera

Ligustrum vulgare

Lythrum virgatum ‘Dropmore Purple’

Osmunda regalis

Prunus x yedoensis

Rosa eglanteria

Salvia ‘Blue Enigma’

Salvia ‘Blue Note’

Salvia uliginosa

Sambucus nigra

Scabiosa ochroleuca

Thalictrum ‘White Splendide’

Thalictrum ‘

Aster unnamed white

Chasmanthium latifolium

Clematis vitalba

Euphorbia cornigera

Fagopyrum dibotrys

Oenothera stricta ‘Sulphurea’

Panicum virgatum ‘Heiliger Hain’

Papaver rupifragum

Rosa ‘The Lady of Shallot’

Salvia uliginosa

Tricyrtis formosana ‘Dark Beauty’

Tropaeolum majus ‘Mahogany’

Photographs | Huw Morgan

Published 3 November 2019

We have just returned from the Climate Strike march in Bath City centre.

Like many of us this year I have been inspired by the school children’s and young students’ worldwide strikes in the name of Fridays for Future, initiated by the example of Greta Thunberg.

Like many of us I have also felt guilt and shame at the fact that we, the older generation, have left it to the young to draw international attention to something that we have been aware of since before these young people were born.

Well, now there is no turning away. There can be no more heads buried in the sand.

During 7 minutes of seated silence this morning I looked around me at all of the people. I thought about how all these like minds and their kind around the globe will have all been trying to make small differences to counteract what we know are the causes of climate change, global pollution and environmental pillage.

I thought about the corporations, businesses and individuals that have benefitted from the destruction of our environment fully aware of the cost to the planet, and reflected on the kind of person who knowingly robs future generations of their future for short term financial profit.

I berated myself; for not engaging, for not doing enough, for consuming too much, for judging others for their apparent profligacy.

I considered how we can have an effect. What can we all do that will make the biggest change ?

The word that entered my head was simplicity. No more than you need.

I intend to make changes. I plan to be stricter with myself. I am sure I will lapse. I know there will be challenges.

It is also essential to enjoy what life offers. To know that it is not only our responsibility to effect change. We must force those that are able to create the biggest and most meaningful changes – governments, manufacturers, agriculture, industry – to face up to their responsibilities to ensure there is a future world that humans can inhabit.

The main ingredients in this dish are from the garden, prepared simply and just enough for one

100g fine green beans

1 pear, about 100g

10 cobnuts, about 20g

A small handful of young salad leaves – lettuce, mizuna, mustard greens, rocket, spinach

1 tablespoon lemon juice

1 tablespoon hazelnut oil

Salt

Put a saucepan of water on to boil.

Remove the tops from the beans and boil for 3 minutes. Drain and refresh in cold water.

Shell the cobnuts and slice coarsely.

Wash and dry the salad leaves.

Put the lemon juice into a large bowl.

Quarter the pear and core. Cut each quarter lengthways into 3 pieces. Put them immediately into the bowl with the lemon juice and toss to coat.

Add the beans, salad leaves and cobnuts.

Drizzle over hazelnut oil.

Season with salt and toss everything together.

Serve.

Recipe & photographs | Huw Morgan

Published 21 September 2019

We have been inundated. A vegetable garden with courgettes running to marrows and tripods of beans hanging heavy and outwitting our best made plans to stagger the crop with three weeks between sowings. The beetroots have ballooned to the size of cricket balls and the chard is straining over the path as if to say “eat me”. Wet weather and warmth in August has put a surge of aromatic growth on the basil and, now that September is cooling, there is pesto to be made if we are to reap the benefits.

Harvesting in August could easily take two days a week and the same again in preparing the pickings for pickling, jam, bottling and freezing. These are good times and in the past we would have pulled together and made an event of it to make light of the workload. Next year we plan to do exactly this at the time of critical mass and set up an industrious production line with friends who are good at picking and friends who are good at preserving. A weekend or two spread over the month will help to manage the glut and people will go home with something to mark their efforts and a memory of the times of plenty for the winter.

Beyond the kitchen garden (and the distraction of beckoning autumn raspberries) and through the gates to the slopes that lie beyond, is the orchard. Planting these trees was my first move after arriving here and they are now in their eighth summer and weighed down with fruit. The apples are yet to come, but the plums have been demanding to keep up with and we find it impossible not to be bothered by the inevitable waste. Yes, of course the excess never goes to waste, the evidence of rodent nibbling and flurries of birds that rise from the windfalls beneath the trees are proof. Working from the ladder up amongst the branches and you find the wasps also gorging and beating you to it if you are not fast enough. The plums ripen over the course of a week, each tree at a slightly different time and with some overlapping.

The gages came first this year and I can say now that I would be happy having nothing but gages. We have four in the plum orchard. This year ‘Bryanston Gage’, ‘Cambridge Gage’ and ‘Early Transparent’ were all productive. They are all superior to the other plums for being aromatic and naturally sweet but ‘Bryanston Gage’ is perhaps the most delicious. As good as apricots and, with the sun in the fruit, warm in your mouth. Morning and evening are the best times to pick. You will be ahead of the wasps when the fruit is still cool with dew, but just before sundown is also a good moment for the fruits are sun warmed and the wasps are early to bed.

I am beginning to doubt whether it was a good idea to have planted pears in the orchard. There are five trees and I can see they will make a good-looking contribution, but the fruits of pears are notorious for dropping just before they ripen and then bruising by the time they are ready to eat. In the kitchen garden we have five cordons grown against the south-facing wall that backdrops the garden and, in terms of convenience, they have proven themselves. The espaliers make picking easy and, as the pears tend to come all at once or over the course of a week, the amount of fruit you have is manageable compared to the orchard trees.

We have five varieties that stagger the cropping over the course of six weeks or so to keep us in pears for the autumn. ‘Beth’ is our first to drop, although we have just eaten the last. I now grow a soft bed of Erigeron under each cordon to act as a cushion for the fruit but, once they start to fall, you need to get out there daily if the mice – and possibly larger rodents – are not to get there first. Although I like the crunch of a nearly ripe pear, two to three days on a shelf sees ‘Beth’ colour to a soft yellow and the fruit ripen to sweet and melting perfection.

Down by the stream we have seven varieties of cobs and filberts; ‘Webb’s Prize’, ‘Gunslebert’, ‘Kentish Cob’, ‘Cosford Cob’, ‘White Filbert’, ‘Pearson’s Prolific’ and ‘Butler’. The trees are in their seventh year and cropping heavily now. This year we have beaten the squirrels who discovered them a couple of years after they started fruiting. St. Philibert of Jumièges, after whom filberts are named, has a feast day on August 20th and from about that time you have to be vigilant. We have learned to pick them early if we are not to lose the entire crop whilst we’re not looking. We put them in a single layer in perforated plant trays to allow plenty of air to circulate and ripen them up in the open barn out of reach of the mice. Sharing what you must leave behind due to the sheer volume of the harvest is one thing, but sharing your hard earned fruits is quite another.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 7 September 2019

We leave the garden now to stand into the winter and to enjoy the natural process of it falling away. The frost has already been amongst it, blackening the dahlias and pumping up the colour in the last of the autumn foliage. Walk the paths early in the morning and the birds are in there too, feasting on the seeds that have readied themselves and are now dropping fast. I have combed the garden several times since the summer to keep in step with the ripening process, being sure not to miss anything that I might want to propagate for the future. The silvery awns on the Stipa barbata, which detach themselves in the course of a week, can easily be lost on a blustery day. This steppe-land grass is notoriously difficult to germinate and a yearly sowing of a couple of dozen seed might see just two or three come through. My original seed was given to me in the 1990’s by Karl Förster’s daughter from his residence in Potsdam, so the insurance of an up-and-coming generation keeps me comfortable in the knowledge that I am keeping that provenance continuing. The seed harvest is something I have always practiced and, as a means of propogation, it is immensely rewarding. Many of the plants I am most attached to come from seed I have travelled home with, easily gathered and transported in my pocket or a home-made envelope. Seedlings nurtured and waited for are always more precious than ready-made plants bought from a nursery but I have learned the art of economy and sow only what I know I will need or think I might require if a plant proves to be unreliably perennial for me. The Agastache nepetoides, for instance, came to me via Piet Oudolf where they grow taller than me in his sandy garden at Hummelo. However, they are unreliable on our heavy soil and need to be re-sown every year. Fortunately, they flower in the same year and I can plug the gaps where they have failed in winter wet with young seedlings sown in March in the frame and planted out at the end of May.

Agastache nepetoides

Over the years, as much by trial and error as by reading about the requirements and idiosyncrasies particular to each plant, I have learned the rules. The Agastache for instance will not germinate if the seed is covered, so they will fail to appear spontaneously in the garden if you mulch or sow and then cover the seed, as I usually do, with a topping of horticultural grit. The seed needs light and should just be gently pressed into the surface so that they can be triggered. The Agastache seed keeps well and is easily sown in spring, but the viability of seed is different from plant to plant. Primula vulgaris gathered and sown directly a couple of years ago saw seedlings germinate readily within a month that same summer. Last year I was busy and waited until September to sow, but the seed had already begun to go into dormancy, an inbuilt mechanism to save it in a dry summer. The overwintering process of stratification, which will unlock dormancy with the freeze, thaw, freeze, saw the seedlings germinate the following spring. The plants consequently took a whole six months longer to get them to the point that I could plant them out into the hedgerows, but I learned and will save myself that delay come the future.

Agastache nepetoides

Over the years, as much by trial and error as by reading about the requirements and idiosyncrasies particular to each plant, I have learned the rules. The Agastache for instance will not germinate if the seed is covered, so they will fail to appear spontaneously in the garden if you mulch or sow and then cover the seed, as I usually do, with a topping of horticultural grit. The seed needs light and should just be gently pressed into the surface so that they can be triggered. The Agastache seed keeps well and is easily sown in spring, but the viability of seed is different from plant to plant. Primula vulgaris gathered and sown directly a couple of years ago saw seedlings germinate readily within a month that same summer. Last year I was busy and waited until September to sow, but the seed had already begun to go into dormancy, an inbuilt mechanism to save it in a dry summer. The overwintering process of stratification, which will unlock dormancy with the freeze, thaw, freeze, saw the seedlings germinate the following spring. The plants consequently took a whole six months longer to get them to the point that I could plant them out into the hedgerows, but I learned and will save myself that delay come the future.

Molopospermum peleponnesiacum

As a rule the umbellifers tend to have a short life and the seed does not keep, so I sow my giant fennel, Astrantia and Bupleurum as soon as the seed is ripe and overwinter it in the cold frame. This year, for the first time. I have sown Molopospermum peleponnesiacum and, though it is a reliable perennial, I am keen to see if I can rear some youngsters. This ferny-leaved umbel is early to rise and I love it for the gloss and laciness of its foliage and the horizontality of its lime green flowers. I have it amongst my Molly-the-Witch peonies and their early presence together is a good one. I’m also simply curious to learn more about the life cycle of this European umbel, as I find I understand a plant better if I know how long it will take to become a parent and what it takes to get it to the point of seeding and germinating successfully.

Molopospermum peleponnesiacum

As a rule the umbellifers tend to have a short life and the seed does not keep, so I sow my giant fennel, Astrantia and Bupleurum as soon as the seed is ripe and overwinter it in the cold frame. This year, for the first time. I have sown Molopospermum peleponnesiacum and, though it is a reliable perennial, I am keen to see if I can rear some youngsters. This ferny-leaved umbel is early to rise and I love it for the gloss and laciness of its foliage and the horizontality of its lime green flowers. I have it amongst my Molly-the-Witch peonies and their early presence together is a good one. I’m also simply curious to learn more about the life cycle of this European umbel, as I find I understand a plant better if I know how long it will take to become a parent and what it takes to get it to the point of seeding and germinating successfully.

Paeonia delavayi

My Paeonia delavayi are the grandchildren of an original plant I grew from seed I collected when I was nineteen and working at the Edinburgh Botanic Gardens. The plants in the garden have started to lose whole limbs this year, which I am putting down to the heat, but it could just as easily be honey fungus. Having a few youngsters in the background is good insurance, but I am sowing the seed fresh because peony seed needs a chill and sometimes two winters before growth appears above ground. The first year is all about the formation of roots so, as a general rule, I never throw a pot of seed out for two years just in case.

Paeonia delavayi

My Paeonia delavayi are the grandchildren of an original plant I grew from seed I collected when I was nineteen and working at the Edinburgh Botanic Gardens. The plants in the garden have started to lose whole limbs this year, which I am putting down to the heat, but it could just as easily be honey fungus. Having a few youngsters in the background is good insurance, but I am sowing the seed fresh because peony seed needs a chill and sometimes two winters before growth appears above ground. The first year is all about the formation of roots so, as a general rule, I never throw a pot of seed out for two years just in case.

Asclepias tuberosa

This is the first year I have grown the tangerine milkweed, Asclepias tuberosa, and would like to get to know it better. It is said to suffer from winter wet, which is a given living where we do in the West Country, so my seed sowing is insurance again and a means of bulking up the little group I have amongst my black-leaved clover. The seed is exquisite, the claw-like pods rupturing on a dry day to spill their silky contents on the breeze. Reading up reveals that the seed also needs winter stratification, so I have sown it now in a lean, gritty compost to ensure it is free-draining and that the seed doesn’t sit wet. A gritty seed compost will ensure the seedlings search for nutrients and grow a good strong root system once they have germinated in the spring. I prefer to top dress with grit rather than soil to inhibit moss and algae build-up, which can cap the pots if they are sitting around for a while in the frame.

Asclepias tuberosa

This is the first year I have grown the tangerine milkweed, Asclepias tuberosa, and would like to get to know it better. It is said to suffer from winter wet, which is a given living where we do in the West Country, so my seed sowing is insurance again and a means of bulking up the little group I have amongst my black-leaved clover. The seed is exquisite, the claw-like pods rupturing on a dry day to spill their silky contents on the breeze. Reading up reveals that the seed also needs winter stratification, so I have sown it now in a lean, gritty compost to ensure it is free-draining and that the seed doesn’t sit wet. A gritty seed compost will ensure the seedlings search for nutrients and grow a good strong root system once they have germinated in the spring. I prefer to top dress with grit rather than soil to inhibit moss and algae build-up, which can cap the pots if they are sitting around for a while in the frame.

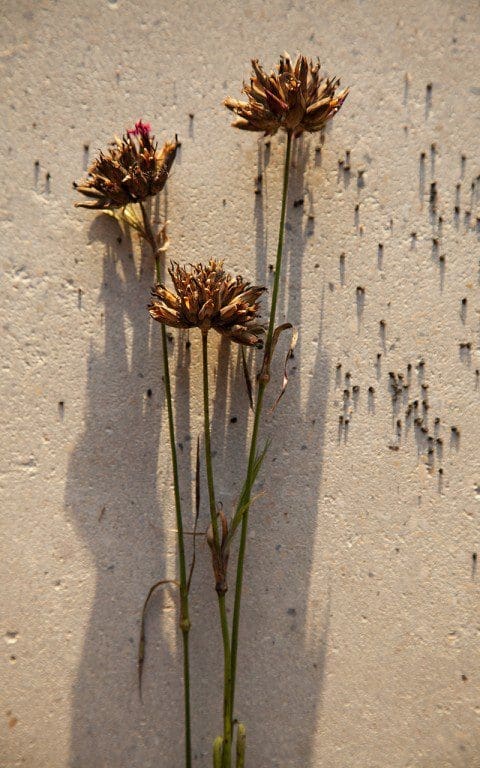

Dianthus carthusianorum (in second image with Achillea ‘Moonshine’)

Although I like to sow most of my hardy plants in the autumn to avoid storing them when they could be beginning their journey, I like a few in hand to simply scatter about and help in the process of naturalising where I want my plants to mingle. The Dianthus carthusianorum are this year’s project, and so I am scattering seed at the tops of my dry banks where I hope they will take in the most open parts of my wildflower slopes by the house. A cast of thousands is easily made up in a handful, but it takes only one to begin a colony.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 17 November 2018

Dianthus carthusianorum (in second image with Achillea ‘Moonshine’)

Although I like to sow most of my hardy plants in the autumn to avoid storing them when they could be beginning their journey, I like a few in hand to simply scatter about and help in the process of naturalising where I want my plants to mingle. The Dianthus carthusianorum are this year’s project, and so I am scattering seed at the tops of my dry banks where I hope they will take in the most open parts of my wildflower slopes by the house. A cast of thousands is easily made up in a handful, but it takes only one to begin a colony.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 17 November 2018 In 2015 I was approached to work as the landscape designer for a new extension at the Garden Museum. The renovations were extensive and it was the second phase of the project for Dow Jones Architects. The first, in 2008, had been to create a series of freestanding structures that moved lightly through the heritage building. This final push would see a new extension reaching out into the garden to create spaces for education, events and a new cafeteria.

The plan for the extension sailed over the footprint of the old knot garden which previously occupied the site, to enclose a new courtyard where the tombs of the Tradescants (father and son) and Captain Bligh take centre stage. The achievements of these three men provided a strong brief for the garden, which reflects their pioneering spirit as adventurers, plant hunters and educators. The Tradescants, once residents of Lambeth, had conceived their garden as a reflection of Eden and so the new cloister was also intended to be a place of sanctuary, where the seasons are brought into close perspective in the centre of the city and the planting is the focus of learning.

We pondered for some time over the removal of the well-loved knot garden, which Lady Salisbury had designed for the museum in 1980, three years after it first opened as the Museum of Garden History. Initially we worked up a series of iterations to abstract the knot garden to see if its memory could be glimpsed in the new design, but the architecture required a more confident forward-looking approach to move the garden, with the museum, into a clearly defined, bold new chapter. However, drawing from the existing sense of place was also important, so the ledger stones from the old graveyard and the bricks from the knot garden were integrated into the path that creates a frame from which to look into the planting. In the corner, where the tombs were close to the path, we extended its reach to allow closer observation of the detailed carvings and inscriptions. An old mulberry and an arbutus were retained in the new design, while an old fig and medlar were carefully moved to beds at the other end of the church. The street-side plane trees, which are protected and provide the museum with its leafy, woodland feeling, were able to have the building so close thanks to a piling system which floats the extension carefully over their root plates.

The street-side planting beneath the London Planes with Euonymus planipes on the left

The street-side planting beneath the London Planes with Euonymus planipes on the left

Aralia cordata, Hakonechloa macra and Anemone x hybrida ‘Honorine Jobert’

Aralia cordata, Hakonechloa macra and Anemone x hybrida ‘Honorine Jobert’

Rubus thibetanus ‘Silver Fern’

Rubus thibetanus ‘Silver Fern’

Viewed from four sides (through glass on three and an open, covered walkway on the fourth) the courtyard garden – called the Sackler Garden after a generous donation from the Sackler Foundation – would become a point of focus within the cloistered enclosure. The new glazed walls would also enhance the London microclimate and help buffer the garden from the wind that uses the River Thames as a corridor in this location. With the exploits of the Tradescants as inspiration, it was a small step to imagine this courtyard as a giant Wardian case – an aquarium-like structure invented in the 19th century to transport exotic and delicate new plant discoveries long distances by sea in a protected environment. The glassy cloister, our metaphorical Wardian case, allowed us to present a garden of curiosities and treasures.

Though an oasis, as a space it is far from hermetic. The planting continues on the street side of the café beneath the planes with a shady carpet of hardy evergreens and woodlanders including Hakonechloa macra and Epimedium sulphureum. A specimen Euonymus planipes was planted to frame the cafeteria door and emerging perennials such as Danae racemosa, Aralia cordata and white persicaria and wind anemone provide the planting with seasonal flux and help make the connection to the green world within. From the street the transparent walls of the café allow an intriguing glimpse of the jungly courtyard planting.

Looking into the cafe across the woodland planting from the street

Looking into the cafe across the woodland planting from the street

The courtyard garden can be seen from the street through the glass walls of the cafe

The courtyard garden can be seen from the street through the glass walls of the cafe

As the courtyard is a deliberately acute focus, it was important that it be a dynamic space that works on every day of the year. When choosing the plants, I felt it was important to continue the spirit of discovery exemplified by the Tradescants and for the plants to tell a story of horticultural history. I also wanted the composition and plant choices to capture the magic of an 18th century botanical engraving and key into the gothic mood of the churchyard and its tombstones.

Modern day plant hunters, such as Sue and Bleddyn Wynn-Jones of Crûg Farm Plants helped provide us with some of the curiosities. Fatsia polycarpa, a rarely seen castor oil plant with deeply divided, elegant fingered foliage, and a Schefflera from Taiwan, complete with precise location notes to bring their provenance to life. Nick Macer of Pan-Global Plants also provided us with some of his wild collections. A giant foliage Dahlia from a trip to Mexico, and flowering gingers for points of exotic interest. I wanted the planting to feel eclectic – a collection – and the exotic edge was important to conjure the feeling of awe and wonder that must be felt by all plant hunters. Canna x ehmannii and Tetrapanax papyrifer have done this at scale and made an immediate impact, whilst more demure curiosities such as Disporum cantoniense ‘Night Heron’ and Epimedium washunense ‘Caramel’ provide the detail once you start to look deeper.

It was of prime importance to the museum that the garden provided a centre of horticultural excellence and the planting has been layered to create an ecosystem where each component in the composition provides a microclimate for its neighbours. The layering has also allowed the play of form and texture to work in combination and, importantly, for the sequencing over the course of the year to reveal change so that the garden is different each time that you visit.

The Sackler Garden at the centre of the new extension. William Bligh’s tomb is in the centre, that of the Tradescants can just be seen on the far right

The Sackler Garden at the centre of the new extension. William Bligh’s tomb is in the centre, that of the Tradescants can just be seen on the far right

The layered planting includes, from left, Canna x ehemannii, Dryopteris erythrosora and Equisetum hyemale. Behind is a seed-collected species Dahlia from Pan-Global Plants. The groundcover is Geranium maccrorhizum ‘White Ness’, a 20th century discovery.

The layered planting includes, from left, Canna x ehemannii, Dryopteris erythrosora and Equisetum hyemale. Behind is a seed-collected species Dahlia from Pan-Global Plants. The groundcover is Geranium maccrorhizum ‘White Ness’, a 20th century discovery.

Canna x ehemannii

Canna x ehemannii

Nandina domestica and Astelia nervosa

Nandina domestica and Astelia nervosa

On the left Tetrapanax papyrifer with Astelia nervosa beneath and Rubus lineatus to the right. Behind are a Schefflera species from Crûg Farm Plants with Nandina domestica

On the left Tetrapanax papyrifer with Astelia nervosa beneath and Rubus lineatus to the right. Behind are a Schefflera species from Crûg Farm Plants with Nandina domestica

Nandina domestica has been planted around the tombstones to reflect its auspicious use as a welcome plant in China, but look carefully and in amongst its stems, like the layers in a rainforest, there is a mingling. Pewter Astelias from the Chatham Islands, delicate maidenhair ferns, the Australian violet, Viola hederacea, and black-leaved Ophiopogon nigrescens in their shadows. I wanted the garden to have plants that had a recognisable use amongst the curiosities too. Wild strawberries, that once would have grown locally in Lambeth, alongside Meyer lemons and passionfruit to remind us how we too often take the provenance of our food for granted.

Having just completed its second summer, the garden is settling in and taking shape in the careful hand of Matt Collins, the museum’s head gardener, a horticultural trainee and a number of volunteers. A planting of deliberate complexity needs a well-informed eye to keep it looking good and it is a delight to return and to see it evolving. The potentially invasive Equisetum hyemale is kept in check and in its place to score its vivid green vertical and exotic climbers scale the cloister pillars.

It has been a privilege to be part of this exciting new chapter and now also to help in developing the next. On Thursday this week the Garden Museum announced Lambeth Green, a new initiative to turn St. Mary’s Gardens alongside the Museum into a community hub, a village green for Lambeth, and also to reach its green tentacles further out into the streets to reconnect to the river and nearby Old Paradise Gardens. With the new incarnation of the Museum as a catalyst, it is now easy to see these exciting possibilities being realised.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photos: Huw Morgan Published 10 November 2018

I have just returned from the South Tyrol where we are helping to heal the scars of construction and seat a new house back into a precipitous mountainside. This north-eastern province of Italy feels more Austrian than Italian and the two-hour drive from Verona plunges you deep into a valley as the Dolomites rise up around you. The spa town of Merano sits at the end of the valley and the slopes that come down to meet the town are farmed proudly and intensively by the locals. Though there was already snow on the peaks, every ledge and terrace up to the treeline was striped with fruit trees. Figs to the lower slopes and then apples, pears, apricots and cherries in immaculate cordons criss-crossing the contours. Beautifully constructed chestnut pergolas sailed over the terraces to make the fleets of vines easily pickable and, in the gulleys that became too steep, the yellowing of the chestnut trees marked their presence at the base of the oak woods above them. Our client helped to make our stay that much more memorable with a meal at a typical Tyrolean eatery on the last night. A winding, single-track road into the orchards threw us off course more than once, but we eventually found the farmhouse, sitting square and noble with the view of the town below. We were welcomed warmly by the family who have occupied this farm for more than seven hundred years and invited into a beautifully simple wood-panelled room. Shared farmhouse tables with chequered tablecloths and lace-covered pendant lights concentrated the experience and a tiled floor-to-ceiling stove sat in the corner of the room to enhance the autumnal feeling. Our host came to the table, offering speck and drawing up a chair beside us to cut and portion it carefully, as he explained the nature of the meal to come. The speck was his own and he told us how it was smoked daily over the course of three months with the prunings from his vines and apple trees. A perfectly portioned apple, rosy as in a fable, sat on the chopping board as a complement, together with schüttelbrot, a South Tyrolean crispbread flavoured with caraway seed. A jug of this year’s new wine, the first of several, helped to lubricate the feast that was to follow. Next came the knödel. Two portions, one red and made of beetroot, the other yellow which, on tasting, we discovered were made with swede, both drenched in a sauce of melted butter and grated parmesan. A meaty plate of home made blood sausage and belly pork on a bed of sauerkraut came next, with more knödel, this time flecked with chopped speck. Finally, a round of hot, charcoal-roasted chestnuts made it to the table. A large cube of butter and schnapps infused with grape skin served to counteract their mealiness and, as we peeled them together, our fingers blackened, I couldn’t help but feel that this same autumn meal must have been eaten in this room for generations. Beetroot ‘Egitto Migliorata’

Beetroot ‘Egitto Migliorata’

INGREDIENTS

Knödel

250g beetroot

1 small onion, finely chopped, about 50g

1 clove garlic, finely chopped

1 tablespoon butter

70g coarse breadcrumbs

30g hard goat cheese or pecorino, finely grated

1 small egg

30-50g plain flour

Small bunch flat leaf parsley, about 1 tablespoon finely chopped

Small bunch dill fronds, about 1 tablespoon finely chopped

Salt and pepper

Sauce

8 tablespoons buttermilk

1 tablespoon soured cream

1 tablespoon freshly grated or creamed horseradish

1 tablespoon olive oil

1 tablespoon lemon juice

Salt

Finely grated hard goat cheese, finely chopped parsley and dill fronds to serve.Serves 2

METHOD It is worth saying that to get the best result you must use breadcrumbs made from the best bread you can get, preferably sourdough, and that the breadcrumbs should be quite coarse. It is also said that the staler the breadcrumbs, the better the knödel. If you can’t get hold of buttermilk use just soured cream or crème fraiche. Heat the oven to 180°C. Wrap the beetroot tightly in foil and bake for 30 minutes to an hour depending on size, until they are soft. Unwrap and leave to cool. Rub the skins off under cold running water. Grate coarsely and put into a mixing bowl. Melt the butter in a small lidded saucepan over a moderate heat. Put in the onion and garlic, stir to coat, then put the lid on the pan and reduce the heat to low. Sweat the onion for about five minutes until it is soft and translucent, but not coloured, stirring from time to time. Remove from the heat, allow to cool, and add to the beetroot. Add all of the remaining dumpling ingredients, apart from the flour, to the beetroot and onion. Stir until all is well combined. Season with salt and pepper. Add the flour, starting with 30g. The dough should remain soft, but start to come together in the bowl. If the mixture seems too wet add flour a little at a time until the right consistency is reached. Do not be tempted to add more flour or the dumplings will be gluey. Leave the mixture to sit for 15 to 20 minutes while you bring a deep pan of water to the boil and make the sauce, by putting all of the sauce ingredients into a bowl and whisking together until emulsified. When the water comes to the boil, turn down to a gentle simmer. Using a knife or spoon divide the dumpling mixture into quarters. Wet your hands with cold water and then take a quarter of the mixture and quickly shape it into a ball. Repeat with the remaining dumpling mixture. Gently lower the dumplings into the hot water, being careful not to burn your fingers. The dumplings will sink. Using a slotted or perforated spoon stir them very gently from time to time to stop them sticking to the bottom of the pan. Cook for 8 to 10 minutes until they float, when they are ready. Carefully remove the dumplings from the pan with a slotted spoon and allow as much water as possible to drain away. Spoon the sauce onto two plates and place two of the dumplings on each plate. Scatter the herbs and cheese over and serve immediately while still hot. Words: Dan Pearson / Recipe and photographs: Huw Morgan Published 3 November 2018 We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage