Cleo Mussi is a mosaic artist who worked with Dan on one of his first Chelsea Flower Show gardens in 1993. Her work is concerned with the influence and importance of nature, man’s place in the ecosystem and the effect we have on it through such practices as intensive agriculture and genetic modification. She brings a critical, politicised and humorous eye to an old folk art tradition.

You originally studied textiles at Goldsmiths. Can you tell me how you arrived at working with mosaic and the connections between these different materials ?

In the late 1980’s I was creating wall pieces using a number of textile processes, printing, weaving and patching together found (essentially affordable) fabrics. Charity shops, car boots and skips were an Aladdins’ cave. I was also studying ceramics at night school. When I left college I began to explore mosaic as a technique and taught myself through trial and error. My work is created from second hand table-ware and ornaments patched and pieced together as with the textile tradition. Originally I wanted to make durable artworks that could be created for both interior and exterior spaces though, due to our climate, very low fired ceramic is not suitable for outside, so all my pieces are interior now.

Cleo’s studio, works in progress and her meticulously organised drawers of raw materials

Cleo’s studio, works in progress and her meticulously organised drawers of raw materials

You worked with Dan on one of his early Chelsea Flower Show gardens. How has the market for your work changed since then ?

My work has evolved very slowly over the years. When I left college, my contemporaries – the YBA’s from Goldsmiths – were having their first Frieze show and I was making hundreds of tiles and glass mounted works, some of which I exhibited in an architect’s office on Brick Lane and also in an empty shop in Hoxton. I had a studio on the Old Kent Road and then later at the South Bank.

In 1992 I was lucky to be accepted for a show at the Royal Festival Hall called ‘Salvaged’ and was then offered a subsidised studio. It was a fantastic space full of makers working in a variety of disciplines inspiring and helping each other. I think it may have been the ‘Salvaged’ exhibition and subsequent press coverage that introduced Dan to my work. It was Dan’s second Chelsea garden, very vibrant and rich with intense colour, and I think the mosaic complemented the planting. It was a real education seeing him create and plan a show garden and being on site during the event. I still have a number of plants that he gave me when he dismantled the garden and they remind me of that time. Plants, like china, hold memories and connect to people and events.

Since then my work has evolved in that my projects are more ambitious and my work is more refined in the making and the conception of the ideas. I create large installations of up to 90 mosaics for new touring shows on grand themes that I am passionate about. Interestingly my clients are still the same sort of people, individuals and establishments that love the work for what it is, for what it is made from and the inherent properties in the china, for the memories they revive, and for the stories that I tell.

The water feature in Dan’s 1993 Chelsea Flower Show garden designed and made by Cleo

The water feature in Dan’s 1993 Chelsea Flower Show garden designed and made by Cleo

Nature is clearly a very important theme in your work, and I know that you are a keen gardener. How do nature, gardens and plants inspire your work ?

I had my own small patch as a child and gathered euphorbia milk and strawberries for my dolls. At an early age my mother taught me about plants; that rue can cause blisters due to photo-allergy and that monkshood is deadly. My mother loved and feared plants. My parents’ oldest friend was Roger Phillips the photographer, ‘Wild Food’ author and mushroom hunter, so this was all part of my childhood. And that Darwin ruled, OK !

My father was an engineer, which is why I love structures and cause and effect and my mother was a human biology teacher, Naturopath and keen gardener. Plants were to be respected, but entice us to take advantage of them to keep the species alive and they in turn take advantage of man. I collect plants like old china, gathered at every opportunity, divided, seeds collected, cuttings taken for my own garden and lovely meals made from produce either grown or from the hedgerow.

Cleo in her garden

Cleo in her garden

Large Collector’s Baskets with Bees, 2014. Photograph courtesy Cleo Mussi.

Large Collector’s Baskets with Bees, 2014. Photograph courtesy Cleo Mussi. Bouquet, 2005. Photograph courtesy Cleo Mussi.

Bouquet, 2005. Photograph courtesy Cleo Mussi.

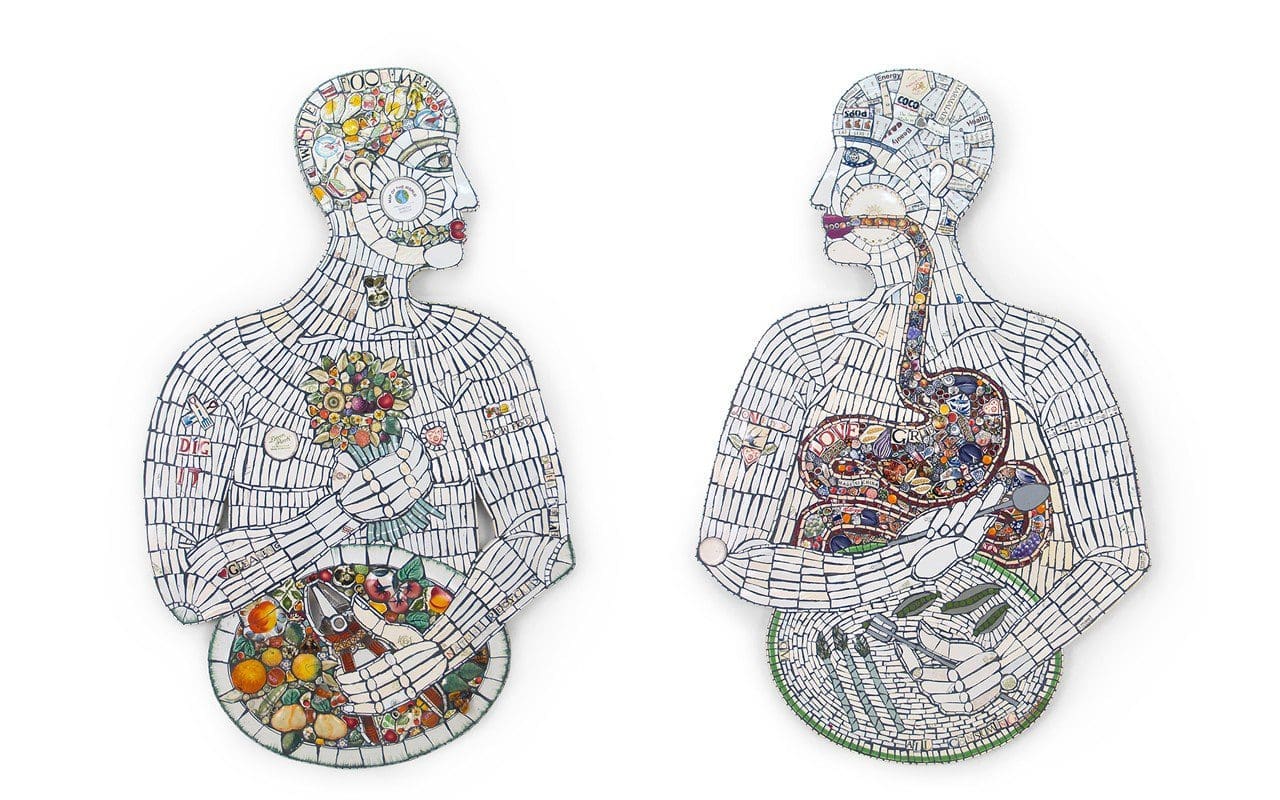

Can you tell me about your recent conceptual shows ‘Pharma’s Market’ and ‘All Consuming’, the themes you explored through them both and why they are important to you ?

These exhibitions connected ideas about food, agriculture and animal husbandry with modern developments in stem cell research, genetic modification and alternative energy. I am intrigued by evolution from the microbial soup in sea vents to archaea, bacteria, viruses, plants and animals; the physical details, the names and the stories and connections on the cellular level. These exhibitions explored the history, the characters, plant hunters, collectors and science. I observe man’s destruction and consumption of natural resources and the impact on our environment, whilst being inspired at the creativity and imagination to solve problems. For example, most recently the discovery of mycelium that neutralise toxins in toxic waste or that bind clean plant waste to form biodegradable packaging, or fungi that help in cancer research. More recently I have become interested in cyborgs and biophysics as well as in the Human Brain Project, the Human Genome Project and, of course, the microbiome; the little gardens in our own bodies yet to be discovered.

Nature Recycles Everything (left) and All Consuming (right), 2014

Nature Recycles Everything (left) and All Consuming (right), 2014

Monoculture Perfection, 2014. Photographs courtesy Cleo Mussi.

Monoculture Perfection, 2014. Photographs courtesy Cleo Mussi.

How has your work changed and developed since you first started ?

When I first started making mosaics, my work was quite simple: tiles, tables, abstract wall panels, naïve faces and fountains for conservatories and gardens, I contributed to many gardening and craft books. Currently my work is generally exhibition focused with a number of commissions alongside mainly for private individuals, but also for arts centres and hospitals and businesses. The pieces are figurative and tell a story. I often have dark tales to tell, but with twists of humour, layers and details hidden beneath the surfaces.

You made a research trip to Japan a few years ago. What did this bring to your work ?

As a family we went to Japan for 4 weeks as my husband Matthew Harris (also an artist) and I were due to create a joint touring show called 50/50 starting at The Victoria Art Gallery in Bath. It was a fantastic experience, and refreshing to develop new work purely from visual information. We were inspired by very different things, but both of our work is constructed from fragments. We incorporated our research and inspirations. In the final exhibition, which unified the work, we had cabinets of sketchbooks, objects and photographs. We visited many of the moss gardens and temples as well as contemporary art and cultural sights. It was from Japan that I developed my interest in Kawaii and Japanese spirit creatures which include such unusual characters as fire-breathing chicken monsters, a red hand dangling from a tree, the spirit who licks the untidy bathroom and other inanimate objects that come to life.

Harajuku Fruit Branch with Blossom and Chrysanths, 2011.

Harajuku Fruit Branch with Blossom and Chrysanths, 2011.

Outlaws – Wanted Dead or Alive, 2016. Photographs courtesy Cleo Mussi.

Your work clearly engages with the history of mosaic craft as a means of storytelling. It also appears to increasingly be concerned with political or social themes.

I think of myself as a modern day folk artist. In the traditional sense of Folk Art my work reflects the world that we live in whilst connecting to bygone days. The mosaic technique is simple, but the content has depth. The work can be read on many levels and I often touch on word play and double meaning. The work on one level is purely decorative celebrating colour form and pattern and, alternatively, on another level has a political content.

Systema Labels: Bees, 2016

Systema Labels: Bees, 2016

Bombus Spiritus Johnson Brothers, 2015. Photographs courtesy Cleo Mussi.

Bombus Spiritus Johnson Brothers, 2015. Photographs courtesy Cleo Mussi.

What are you working on at the moment ?

I am creating a new touring show which I hope to take to London as well as nationwide. The ideas are in their infancy, but I am looking at how weeds have evolved and the relationship between them and man’s migration and establishment of agricultural settlements. I am interested in the symbiotic relationship that we have with plants and the delicate balance of what we ingest as cure or poison and what we cultivate as food or weed.

I love the colloquial names ‘Bunny Up The Wall’ (Ivy-leaved toadflax), ‘Bomb Weed’ (Rosebay willow herb), ‘Jack Jump About’ (Ground elder), ‘Kiss Me Over The Garden Gate’ (Pansy), ‘Summer Farewell’ (Ragwort) and all the Devils; claws, blanket, tongue, fingers, etc. Many of these weeds were migrants, and yet they define our landscape. I am intrigued by this language that comes from the people who worked the land, often describing the plants and ‘weeds’ in terms of endearment or loathing from their working days; knowledge passed down by example and word of mouth.

What do you find to be the challenges and differences between self-generated work and commissions ?

Time is always the master, and the work is very time-hungry to physically create. I constantly alternate between making work that people would like to live with and thus support the creation of the more challenging pieces. I alternate between smaller works, which I make in series, and the large one-off exhibition pieces that can take weeks to make. I love to take on new large commissions as these often bring new ideas into the mix that I may otherwise not discover. Recent joys were a Donkey with Baskets for Vale Community Hospital in Dursley, a giant magic cat inspired by Edward Bawden, a piece about education called ‘Ode To Ed’ at Prema Arts in Uley and a Solar Panel Installation Worker for Primrose Solar in London. Pretty diverse.

Corn Cob with Dark Kernel (left) and Asparagus (right), 2014

Corn Cob with Dark Kernel (left) and Asparagus (right), 2014

Carrots (left) and Broccoli with Dots (right), 2014. Photographs courtesy Cleo Mussi.

Carrots (left) and Broccoli with Dots (right), 2014. Photographs courtesy Cleo Mussi.

Can you tell me about your role in The Walled Garden at The Museum in the Park in Stroud ?

‘Patron of The Walled Garden’. I am rather pleased with my new title. I have been asked to create a planting scheme on a shoe-string budget for this special space. The garden is about a third of an acre and is managed by teams of volunteers. Essentially the back garden is open at The Museum in The Park. It was untouched for over 50 years and it has now been given a new life as a place for education, contemplation and creativity for the community. Since 2008 numerous volunteers have contributed time and knowledge to this space. Starting with secret artist donations to raise funds and teams of people excavating and clearing, sifting, weeding planting and now watering. The hard landscaping and education space was commissioned and completed last year and now it’s time to put the icing on the cake. So, with just a few hundred pounds, we have purchased a handful of plants and the rest, as with my own garden, have been gleaned and propagated, split and gifted to create a new garden in about 14 sections. Dan kindly donated a huge and varied selection of irises, which have been combined with a collection from Mr. Gary Middleton, so we will have quite a show this May.

Kyushu Tea Vases, 2011.

Kyushu Tea Vases, 2011.

Bento Box, 2011. Photographs courtesy Cleo Mussi.

Bento Box, 2011. Photographs courtesy Cleo Mussi.

Starting from scratch enables us to make bold decisions; not to use blanket herbicides, our weeds are ‘hand picked’. We have introduced English bluebells under the mixed hedges and a wild seed mix and snakeshead fritillaries in the newly planted orchard, rather than lawn grass. The beds are divided into sections and aptly named ‘Bobbly Border’, ‘Bonkers Border’, ‘The Hot Bed’, the ‘Red Hot Bed’ , ‘The Purple Complementary’ and the more gentle ‘White Border’ and ‘Fernery’. Being a walled garden it’s a very hot space with very little shade, so this has been both exciting and challenging and it will also be interesting to see what survives through the winter. So the garden will evolve. This is our first season and the garden has established incredibly well. I think it has a secret underground water source. We are open to the public and anyone is welcome to visit. Coming up now are species snowdrops, ‘Wasp’ being my favorite, an auricula theatre, a tulip bed for cutting (inspired by Dan) and then later -fingers crossed – a bonkers display of zinnias for bedding, as well as all the other aspects of the garden in each season.

Cleo holding a recently completed Tussie Mussie, 2016

Cleo holding a recently completed Tussie Mussie, 2016

Cleo’s work can be seen in these upcoming exhibitions;

March 18th – May 7th

‘Pour Me’

The Devon Guild of Craftsmen

Riverside Mill

Bovey Tracey

Devon

TQ13 9AF

Mid-May for 6 weeks during the Hay Literature Festival

‘All Consuming’

Brook Street Pottery

Hay-on-Wye

Hereford

HR3 5BQ

May 6th & 7th and 13th & 14th

Select Trail

Open Studios

Frogmarsh Mill

South Woodchester

Stroud

GL6 7RA

Instagram: cleomussimosaics

Interview: Huw Morgan / All other photographs: Emli Bendixen

At the height of summer, when all you want to be eating are salad, peas, broad beans and cucumbers, it is easy to resent the space taken up by the winter vegetables. But the time spent sowing, weeding, hoeing and watering them through the hot months is amply repaid come this time of year. We have been eating beetroot, parsnips, turnips, swedes, celeriac and carrots for several months now and, together with our stored potatoes and onions and a wide assortment of brassicas, we have been almost self-sufficient for vegetables. The greengrocer only sees me if I need lemons, oranges or some of the more exotic fruits available at this time of year like pomegranates, persimmons or Seville oranges.

The brassicas and roots are our winter bounty but, although we have enjoyed the hearty roast vegetables and mash, there comes a point when we pine for a crunch and for fresh, clean flavours. Without a polytunnel or greenhouse winter salad hasn’t been possible here yet, and I refuse to buy tasteless bags of salad so we rely upon the radicchio and chicory that were sown last spring, eaten in the summer and then left in the ground. We always miss the chance to sow them for a winter harvest, but these rogues from the summer are hearting up now, and add to this salad of raw winter roots.

The freckled leaves of ‘Castelfranco’ make a pretty addition to the plate, but any of the more common dark red forms would provide a dramatic contrast. The wider a variety of shape and colour you can get in your selection of vegetables the more attractive the salad will look. Here I have used the striped beetroot ‘Chioggia’ and orange ‘Burpee’s Golden’. The varied colours of heritage carrots also add to an appealing mix.

The balance of sweet, savoury, earthy, bitter and peppery flavours provided by the vegetables selected here makes for a varied eating experience, but the salad could be made with any combination of three of the roots if you do not have access to them all. Thinly sliced fennel would also be a good addition and, although the frost has ravaged our winter crop of bulbs, the remaining foliage is still delicious for its aniseed flavour and addition of green. Radish, mooli or kohlrabi could also be substituted.

Seville oranges are just coming to the end of their season. When unavailable replace with a 50/50 mix of lemon and orange.

This salad is particularly good with roast chicken, roast pork, sliced ham or a cold chicken and ham pie.

Ingredients

SALAD

Juice of 1 lemon

2 medium carrots – different colours if possible

1 small parsnip

2 small beetroot – different colours if possible

½ small turnip

½ small swede

1 Cox’s apple

¼ medium celeriac

1 small head radicchio

2 tbsp finely chopped parsley

2 tbsp fresh fennel or dill herb fronds

DRESSING

50ml soured cream

1 egg yolk

2 tsp honey

1 tsp finely grated horseradish or English mustard

25ml rapeseed or other light oil

Juice of 1 Seville orange

Very finely grated zest ½ Seville orange

Salt

Some reserved fennel fronds

3 tbsp tablespoons pomegranate seeds

3 tbsp broken walnuts

Serves 6

Method

First prepare two bowls of iced water. Add the lemon juice to one of them.

Trim and peel the carrots and parsnip, then shave thin ribbons off the length of each with a vegetable peeler. Put them all into the bowl of plain iced water. If you are using dark red or purple carrots put them in a separate bowl of iced water.

Trim and peel the beetroot. Using a mandolin or very sharp knife slice as thinly as possible into rounds. Striped or pale coloured beetroot (orange, yellow or white) can be added to the water bowl containing the carrots and parsnip. Purple beetroot will need a separate bowl of iced water or can be added to that containing the purple or red carrots.

Peel the turnip and swede and grate coarsely.

Slice the apple as thinly as possible and put into the bowl of acidulated water.

Peel the celeriac. Cut into slices about a centimetre thick. Using a mandolin or very sharp knife slice as thinly as possible. Add to the bowl of acidulated water.

Remove the leaves from the radicchio and tear the soft part of the leaves away from the coarse ribs, which aren’t used. Tear the leaves into pieces roughly 4cm square.

To make the dressing put the egg yolk in a bowl, whisk with a fork, then add all of the other ingredients and whisk again until well combined. Taste for seasoning. You may need to add more honey, salt or horseradish to taste. The dressing needs to be fairly strongly seasoned as the flavour is diluted once mixed with the salad. Finally stir in the finely chopped parsley.

Heat a small heavy frying pan. Add the walnuts and allow to scorch on one side. Remove from the pan and allow to cool.

Drain the vegetables and apple and pat dry on a clean tea towel. Put in a large bowl. Keep the dark roots to one side. Add the radicchio and fennel fronds to the bowl. Using your hands toss the salad very gently to distribute the different vegetables evenly. Pour over two thirds of the dressing and use your hands again to gently mix the salad ensuring everything is well coated. Add more dressing if required, however the vegetables should just be lightly coated, not swimming. Now add the dark beetroot and carrots and toss the salad again very quickly to avoid turning the whole salad pink.

Transfer the salad to a serving plate or divide between individual plates. Spoon on a little more dressing then scatter over the pomegranate seeds, scorched walnuts and reserved fennel fronds.

Recipe & Photographs: Huw Morgan

The Lonicera fragrantissima broke the first flower buds in the last week of December, closing the year with a perfumed offering on the cool air. At the moment, for this is still a young garden, it is one of the few flowers that brave the shortest days. Also flowering now is the witch hazel, Hamamelis x intermedia ‘Barmstedt Gold’. Its spidery yellow flowers have a light bergamot fragrance and some sprigs for the house are precious for their scarcity. Winter honeysuckle itself is an easy thing. Indeed, it will grow in the toughest of places on next to nothing. It was one of the solitary survivors amongst the undergrowth when I moved to the garden in Peckham almost twenty years ago. I dug it out, saving a layering to pass on and not erase it completely from memory. With limited space I wanted something more choice in its place back then and so enjoyed it vicariously in client’s gardens until we moved here and had room for it.

Lonicera fragrantissima

Lonicera fragrantissima

Hamamelis x intermedia ‘Barmstedt Gold’

Hamamelis x intermedia ‘Barmstedt Gold’

Though its ease of cultivation and eagerness to take its own territory, like lilac, is less welcome where space is limited, where you can afford to give it the opportunity to flourish, it is a thing to treasure. I’m pleased to have it at my fingertips for its refusal to bow to the season and have planted it at the end of the barns, on a rubbly mound where an aged bullace stands next to the compost heaps. Little grew there except nettles, but I saw in this leftover place a perfect position to let it take hold.

A little plant, from an easily taken cutting, went in two winters ago and it already has a presence, one arching limb bigger and more fully formed than the next and the flowers springing from the lateral growth of the previous year. It is never fully deciduous until the push of bright new leaves in the spring and the pale, waxy flowers are held amongst a scattering of yellowing foliage. Look closely and the blooms with their splayed yellow anthers are clearly those of honeysuckle and they smell like it too. I will leave the shrub to attain full size at 3 metres and not curtail it by regular pruning, although it responds well to the clippers and makes a fine scented hedge. In time I plan to remove whole branches and bring them into the house. Captured indoors the perfume is pervasive, but never overpowering like that of paperwhites.

Viola odorata

Viola odorata

I have never quite fathomed why so many winter-flowering plants possess a perfume because, although the scent is designed to attract pollinators from a distance, the majority of insects are in hibernation when they are in flower. However, it is a lovely thing to come upon when you are expecting less. Placing is all important where these moments can be fugitive on winter air, and the perfume of the lonicera is held in the stillness around the barns. As it is hungry at the root I have planted a drift of Viola odorata at its base. I believe them to be florist’s violets from the time when the land here was a market garden. There was a self-seeded colony in the lawn in front of the house, which I saved when the re-landscaping took place last year. Rummage amongst the foliage and the very first flowers are already present, their inimitable powdery scent providing a foretaste of spring. Amongst the viola I am going to add one of the earliest of the snowdrops, Galanthus elwesii ‘Mrs. McNamara’, which also started flowering at the turn of the year and is sweetly scented of honey. Another layer to this winter collection and one that is always welcome at this fallow time.

Galanthus elwesii ‘Mrs. McNamara’

Galanthus elwesii ‘Mrs. McNamara’

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

This winter’s notable run of frosts has already marked this year as distinct from the mild run we’ve had of late. We have woken again and again to a glistening world where footfall comes with a crunch and the fields and hedges are unified by the white freeze. The frost has come with clear blue skies and, as the sun has crept over the folds in the land, the colours of winter have bled back in with the thaw of its extending fingers. These are the days when I am pleased for the skeletons of the last growing season. This early into the winter most are still standing and those that will continue to do so are already showing their stamina. The bronze fennel is one of the best. It is already naturalising here, seeding around the rusty barns and even where last year’s bonfire saw them burn in the spring clear up. I have them at the front of the house with the twisted remains of the apricot evening primrose and they have been alive with birds. A flitting wren and robins rummaging around amongst their stems where the seed has fallen and great tits stripping the seed from the architecture of umbels.

Bronze fennel

In the new garden, where I am working around the old stock beds for now, I am grateful for the reminder that I must plan for these bare bones in its winter incarnation. I want it to be a place that is as fascinating and beautiful in its death throes – and whilst resting – as it is in summer. The volunteer sunflowers left from the garden’s previous chapter, and whose seeds are stripped by the birds, are also a prompt that the garden should be as much a feeding ground as a place to study the decay and drawing back of winter. Where the ground now lies fallow, waiting and empty we will have life and light and change as the skeletons age and bleach and topple towards spring.

Bronze fennel

In the new garden, where I am working around the old stock beds for now, I am grateful for the reminder that I must plan for these bare bones in its winter incarnation. I want it to be a place that is as fascinating and beautiful in its death throes – and whilst resting – as it is in summer. The volunteer sunflowers left from the garden’s previous chapter, and whose seeds are stripped by the birds, are also a prompt that the garden should be as much a feeding ground as a place to study the decay and drawing back of winter. Where the ground now lies fallow, waiting and empty we will have life and light and change as the skeletons age and bleach and topple towards spring.

Molinia caerulea ssp. arundinacea ‘Transparent’

The Molinia caerulea ssp. arundinacea ‘Transparent’ that were standing until so very recently have already given way to the weather and lie strewn. I will remember their habit and plant them away from the path so that, when they do fall, their sheaves can be enjoyed akimbo. Their lack of endurance as skeletons can be forgiven if they are in association with plants that keep it together and stand for longer. A drift of the buff powder-puffs of Aster pyrenaeus ‘Lutetia’ or A. x herveyi with its seed now blown free to reveal their light-reflecting starry calyces. Another grass perhaps, such as the Panicums, to arrest the sun in their plumage. The aptly named P. ‘Cloud Nine’ is showing itself to be one of the best I have here, standing tall, the elegant foliage now the colour of straw and parchment, the seedheads large and open. Pale on a dry day, yellowed when it is damp.

Molinia caerulea ssp. arundinacea ‘Transparent’

The Molinia caerulea ssp. arundinacea ‘Transparent’ that were standing until so very recently have already given way to the weather and lie strewn. I will remember their habit and plant them away from the path so that, when they do fall, their sheaves can be enjoyed akimbo. Their lack of endurance as skeletons can be forgiven if they are in association with plants that keep it together and stand for longer. A drift of the buff powder-puffs of Aster pyrenaeus ‘Lutetia’ or A. x herveyi with its seed now blown free to reveal their light-reflecting starry calyces. Another grass perhaps, such as the Panicums, to arrest the sun in their plumage. The aptly named P. ‘Cloud Nine’ is showing itself to be one of the best I have here, standing tall, the elegant foliage now the colour of straw and parchment, the seedheads large and open. Pale on a dry day, yellowed when it is damp.

Aster pyrenaeus ‘Lutetia’

Aster pyrenaeus ‘Lutetia’

Aster x herveyi

Aster x herveyi

Panicum ‘Cloud Nine’

Remarkable now, and noteworthy for being at its very best in the winter, is Glycyrrhiza yunnanensis. The Yunnan liquorice is perfectly hardy here and has taken well to our sunny slopes. I first saw it on an autumn visit to Piet Oudolf’s garden with my friend and gardener from the Millennium Forest, Midori. In typical fashion Piet offered us the seed and we both took a handful of the extraordinary pods. The following spring we sowed the seed, Midori in Hokkaido and me back here back in Somerset. The plants in Japan have struggled to attain stature, despite coming through a winter beneath an eiderdown of snow, but mine have soared to well over head height and have spawned further generations which I am now nurturing in the frame for the spring planting of the new garden.

Panicum ‘Cloud Nine’

Remarkable now, and noteworthy for being at its very best in the winter, is Glycyrrhiza yunnanensis. The Yunnan liquorice is perfectly hardy here and has taken well to our sunny slopes. I first saw it on an autumn visit to Piet Oudolf’s garden with my friend and gardener from the Millennium Forest, Midori. In typical fashion Piet offered us the seed and we both took a handful of the extraordinary pods. The following spring we sowed the seed, Midori in Hokkaido and me back here back in Somerset. The plants in Japan have struggled to attain stature, despite coming through a winter beneath an eiderdown of snow, but mine have soared to well over head height and have spawned further generations which I am now nurturing in the frame for the spring planting of the new garden.

Glycyrrhiza yunnanensis

Their skeletons have been almost immune to the winter. Last year we had to fell them in the spring and cut their glory short to make way for the new growth. The cinnamon-coloured stems, which in summer are clothed with fine, pinnate foliage, stand at over two metres. The seedpods, which are the end result of a pretty but rather insignificant clutch of lilac, pea-like flowers, are as good as any seedpod gets. The size of a hens egg, and like a spiny fir cone in appearance, they are covered in rust-brown hairs that are bristly to the touch and hold the hoar frost as though it was designed for their armature. I will march them through the new garden where they can shine in the cold months and provide us with a place that will celebrate this apparent down time.

Glycyrrhiza yunnanensis

Their skeletons have been almost immune to the winter. Last year we had to fell them in the spring and cut their glory short to make way for the new growth. The cinnamon-coloured stems, which in summer are clothed with fine, pinnate foliage, stand at over two metres. The seedpods, which are the end result of a pretty but rather insignificant clutch of lilac, pea-like flowers, are as good as any seedpod gets. The size of a hens egg, and like a spiny fir cone in appearance, they are covered in rust-brown hairs that are bristly to the touch and hold the hoar frost as though it was designed for their armature. I will march them through the new garden where they can shine in the cold months and provide us with a place that will celebrate this apparent down time.

Glycyrrhiza yunnanensis seedheads

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Glycyrrhiza yunnanensis seedheads

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan This year we have based ourselves here for three full weeks to see out the last of December and welcome in the new year. Your eye is free to travel further in this wintry landscape and it has been good to follow by venturing beyond our boundaries. Slowly – for it took a few days to get into the routine of it – a walk has started the day. We have been both up and down the valley and high onto the exposed ground of Freezing Hill to experience the roar of the wind in the beeches and to understand why it has its name, as it whips up the slopes that run down the other side to Bristol. Always looking back to see how we fit into the folds, we have contributed to our knowledge of muddy ways, well-worn tracks, breaks in hedges and crossing points back and forth across the ditches and streams. Marking our way – for nearly every field has at least one – are the ancient ash pollards.

Ash wood burns green so the trees have value and owning enough pollards would keep you in firewood if you attended to them in rotation. The pollards regenerate easily from cuts made above the grazing line, so that they can grow away again unhindered by the cattle. Usually standing solitary on a steeply sloping pasture (where they add to their usefulness by providing summer shade for livestock) the pollards are stunted by decades of decapitation and, in combination, make an extraordinary trail of characters in the landscape.

We have stopped at each one to take in their histories and their winter slumbers that expose their distinct personalities. Some are hollow to the core, the new limbs surviving on little more than a thin rim of bark. Inside the hollows map the decay and hold the damp and the smell of it even in the dry months. The halo of new growth that breaks from the old forms a crown of fresh limbs that in ten or twelve years are big enough for harvesting. To date the cycle has continued until the trees are exhausted and split and fail.

Of course, we are waiting patiently to see if the pollards survive the chalara dieback that is moving across the country and is already in the valley. Neighbours who have lived here a lifetime recount how different the landscape was when the elms rose up in the hedgerows, but it is the ash and their potential demise that will now be cause for a new perspective.

The solitary ash pollard on The Tump

The solitary ash pollard on The Tump

We have a solitary pollard on the west facing slopes of The Tump. The farmer who lived here before us climbed the tree to harvest the wood in the year he died. The tree must have been huge once, the trunk striking the form of an imposing female torso. An interesting presence given the fact that the ash was once seen as the feminine counterpart to the father tree, the oak. When we arrived here there was just a summer’s regrowth and I set to immediately planting thirty new ash in the hedgerows to provide us with our own rotation. So far – and I remain hopeful – they have done well, despite our mother tree showing a reluctance to throw out another set of limbs and the forecasts that estimate a five percent survival for ash in this country.

We have let the grass grow long on the slopes that are too steep for haymaking around our pollard and in six years there are the beginnings of a new habitat. An elder has sprung from high in her crown and a black and sinister fungus from the side that has refused to regrow branches. Around her there is a skirt of bramble and young hawthorns where the birds have previously settled in her branches and stopped to poop. I plan to plant an oak I grew from an acorn amongst them. New life around the old and a suitable partner, I hope, for a changeable future.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

December reveals the bones of the landscape. Mud where there was grass, bare stems where there was foliage and, by this late in the year, almost everything drawn back and in retreat. Not so the Glastonbury Thorn. Missing the winterising gene that triggers dormancy and stirring when there is barely enough light or warmth to sustain growth above ground, Crataegus monogyna ‘Biflora’ is pushing against the flow. A scattering of young foliage is greening limbs that only recently were fully clothed and a push of pale flowers braving the elements.

Flowering twice, once in spring in celebration of the resurrection and then again at Christmas to mark the birth of Jesus, the habits of the Glastonbury Thorn are understandably surrounded by legend. Joseph of Arimathea was reputed to have visited Glastonbury with the Holy Grail. Thrusting his staff into Wearyall Hill it sprouted and grew into the original tree which, for superstitious reasons, was cut down and burned during the English Civil War. A subsequent tree (planted from cuttings taken by locals and fostered since then in the area) replaced it in 1951, only to be vandalised in December 2010. Its limbs were crudely dismembered and subsequent growth the following March was mysteriously rubbed out. Then, on 1st April 2012 a sapling grafted from a descendant of the pre-1951 specimen was planted again on the site, only to be snapped in half and irreparably damaged sixteen days later.

The Glastonbury Thorn by the orchard gate

The Glastonbury Thorn by the orchard gate

As I like a story, and the thought of sweetening a sad one, I set out to find a tree when we moved here to give the magical thorn another stronghold. As all the plants are reputed to come from grafts taken from the original tree, the search revealed how few people grow it and how hard it is to find. Our friend and fellow gardener, Hannah, made me a present of one for my fiftieth birthday and now here it is, by the gate to the pear orchard, in all it’s curiosity.

Though a branch growing in the Churchyard of St. John’s, Glastonbury is taken to the Queen every year on December the 8th by the Vicar and Mayor of Glastonbury, I am too superstitious myself to pick a sprig for the house. Folklore has it that it is unlucky to bring hawthorn over the threshold and, to compound the story, they say the original tree took out the eye of the man who felled it during the Civil War. I like my tree where it is because the flowers draw me out into a closing-down landscape, which is charged just a little by their miraculous show on the darkest days of the year.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

The bare-root plants arrived at the end of November, bagged up at the nursery as soon as the foliage fell from the branches and bundled together ready to make the move to new ground. Just an hour after delivery the roots were plunged in the trough to rehydrate them and then the bundles lined out in a trench in the kitchen garden until I was ready to plant them in their final positions. I love this moment, which marks the transition between the activity of a garden tended through the growing season to the industry of winter preparation. It is now that the real work is happening. As we turn the soil to let the frost do the work of preparing it for spring planting, or spend an hour shaping the future of a new tree so that its branches are given the best possible opportunity, we imagine the growing garden fully-clothed and burgeoning. Bare-root whips of hawthorn and wild privet

I buy my bare-root plants from a local wholesale nursery just fifteen miles from here and welcome the fact that they haven’t had to travel far to their new home. This year the two-year-old whips are the bones of a new hedge that will hold the track which runs behind the house and along the contour of the slope to the barns. It replaces a worn out hedge of bramble and elder that was removed when we built the new wall and will provide shelter to the herb garden below when we get the cold north-easterlies. It will also connect with the ribbons of hedges that make their way out into the landscape. Keeping it native will allow it to sit easily in the bank and to play host to birds up close to the buildings.

This year my annual ambition to get bare-root material in the ground before Christmas has been achieved for the very first time. It is best to get bare-root plants in the ground this side of winter if at all possible. They may not look like they are doing much in the coming weeks but, if I were to lift a plant from my newly planted hedge at the end of January, it would already be showing roots that are active and venturing into new ground. With this advantage, when the leaves pop in the spring the plants will be more independent and less reliant on watering than if planted at the back end of winter.

Bare-root whips of hawthorn and wild privet

I buy my bare-root plants from a local wholesale nursery just fifteen miles from here and welcome the fact that they haven’t had to travel far to their new home. This year the two-year-old whips are the bones of a new hedge that will hold the track which runs behind the house and along the contour of the slope to the barns. It replaces a worn out hedge of bramble and elder that was removed when we built the new wall and will provide shelter to the herb garden below when we get the cold north-easterlies. It will also connect with the ribbons of hedges that make their way out into the landscape. Keeping it native will allow it to sit easily in the bank and to play host to birds up close to the buildings.

This year my annual ambition to get bare-root material in the ground before Christmas has been achieved for the very first time. It is best to get bare-root plants in the ground this side of winter if at all possible. They may not look like they are doing much in the coming weeks but, if I were to lift a plant from my newly planted hedge at the end of January, it would already be showing roots that are active and venturing into new ground. With this advantage, when the leaves pop in the spring the plants will be more independent and less reliant on watering than if planted at the back end of winter.

The new hedge will hold the track behind the house and act as a windbreak for the herb garden below the wall

Slit planting whips could not be easier. A slot made with a spade creates an opening that is big enough to feed the roots into so that the soil line matches that of the nursery. I have been using a sprinkling of mycorrhizal fungus on the roots of each new plant to help them establish – the fungus forms a symbiotic relationship with the roots and mycorrhiza in the soil, enabling them to take in water and nutrients more easily. A well-placed heel closes the slot and applies just enough pressure to firm rather than compact the soil. The plants are staggered in a double row for density with a foot to eighteen inches or so between plants.

The new hedge will hold the track behind the house and act as a windbreak for the herb garden below the wall

Slit planting whips could not be easier. A slot made with a spade creates an opening that is big enough to feed the roots into so that the soil line matches that of the nursery. I have been using a sprinkling of mycorrhizal fungus on the roots of each new plant to help them establish – the fungus forms a symbiotic relationship with the roots and mycorrhiza in the soil, enabling them to take in water and nutrients more easily. A well-placed heel closes the slot and applies just enough pressure to firm rather than compact the soil. The plants are staggered in a double row for density with a foot to eighteen inches or so between plants.

Adding mychorrizal fungi to newly planted hedging whips

I have planted a new hedge or gapped up a broken one every winter since we moved here and I have been amazed at how quickly they develop. They are part of our landscape, snaking up and over the hills to provide protection in the open places and it is a good feeling to keep the lines unbroken. This one has been planned for about three years, so I have been able to propagate some of my own plants to provide interest within the foundation of hawthorn and privet. Hawthorn is a vital component for it is fast and easily tended. It provides the framework I need in just three years and the impression of a young hedge in the making not long after it first comes into leaf. I have planted two hawthorn whips to each one of Ligustrum vulgare, which is included for its semi-evergreen presence. I like our wild privet very much for its delicate foliage, late creamy flowers, shiny black berries and the fact that it provides welcome winter protection for birds.

Woven amongst this backbone of bare-roots plants, and to provide a piebald variation, are my own cuttings and seed-raised plants. A handful of holly cuttings – taken from a female tree that holds onto its fruit until February – and box for more evergreen. The box were rooted from a mature tree in my friend Anna’s garden in the next valley. I do not know it’s provenance, but it is probably local for there is wild box in the woods there. I like a weave of box in a native hedge as it adds density low down and an emerald presence at this time of year.

Adding mychorrizal fungi to newly planted hedging whips

I have planted a new hedge or gapped up a broken one every winter since we moved here and I have been amazed at how quickly they develop. They are part of our landscape, snaking up and over the hills to provide protection in the open places and it is a good feeling to keep the lines unbroken. This one has been planned for about three years, so I have been able to propagate some of my own plants to provide interest within the foundation of hawthorn and privet. Hawthorn is a vital component for it is fast and easily tended. It provides the framework I need in just three years and the impression of a young hedge in the making not long after it first comes into leaf. I have planted two hawthorn whips to each one of Ligustrum vulgare, which is included for its semi-evergreen presence. I like our wild privet very much for its delicate foliage, late creamy flowers, shiny black berries and the fact that it provides welcome winter protection for birds.

Woven amongst this backbone of bare-roots plants, and to provide a piebald variation, are my own cuttings and seed-raised plants. A handful of holly cuttings – taken from a female tree that holds onto its fruit until February – and box for more evergreen. The box were rooted from a mature tree in my friend Anna’s garden in the next valley. I do not know it’s provenance, but it is probably local for there is wild box in the woods there. I like a weave of box in a native hedge as it adds density low down and an emerald presence at this time of year.

A home-grown box cutting

Raised from seed sown three years ago, taken from my first eglantine whips, are a handful of Rosa eglanteria. They make good company in a hedge, weaving up and through it. A smattering of June flower and the resulting hips come autumn earn it a place, but it is the foliage that is the real reason for growing it. Smelling of fresh apples and caught on dew or still, damp weather, they will scent the walk as we make our way to the barns.

The final addition are part of a trial I am running to find the best of the wild honeysuckle cultivars. I have ‘Graham Thomas’ and the dubiously named ‘Scentsation’, but Lonicera periclymenum ‘Sweet Sue’ is the one I’ve chosen for this hedge, as it is supposed to be a more compact grower and freer-flowering. There are three plants, which should wind their way through the framework of the hedge as it develops and add to the perfumed walk. Wild strawberries will be planted as groundcover in the spring to smother weeds and to hang over the wall where they will make easy picking.

A home-grown box cutting

Raised from seed sown three years ago, taken from my first eglantine whips, are a handful of Rosa eglanteria. They make good company in a hedge, weaving up and through it. A smattering of June flower and the resulting hips come autumn earn it a place, but it is the foliage that is the real reason for growing it. Smelling of fresh apples and caught on dew or still, damp weather, they will scent the walk as we make our way to the barns.

The final addition are part of a trial I am running to find the best of the wild honeysuckle cultivars. I have ‘Graham Thomas’ and the dubiously named ‘Scentsation’, but Lonicera periclymenum ‘Sweet Sue’ is the one I’ve chosen for this hedge, as it is supposed to be a more compact grower and freer-flowering. There are three plants, which should wind their way through the framework of the hedge as it develops and add to the perfumed walk. Wild strawberries will be planted as groundcover in the spring to smother weeds and to hang over the wall where they will make easy picking.

Planting a new field boundary hedge on new year’s day 2011

Planting a new field boundary hedge on new year’s day 2011

The same hedge six years later

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

The same hedge six years later

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan As Dan wrote recently, at this time of year we often find that some of our pumpkins have started to deteriorate in storage. These are usually the varieties that contain more water. Unless damaged or frosted, those higher in dry matter generally have a longer storage life.

Last year, and due to a lack of storage space while our building works were taking place, we were faced with a depressingly large number which were fast heading in only one direction. The compost heap. Determined not to lose such a good harvest I resolved to find a way of preserving them. However, there is only so much soup and puree that the freezer can take. Or that you want to eat.

I had had success the previous year developing a recipe for brown sauce, which had been initiated by a similar desire to make the most of the windfall apples from the old orchard in our top fields. Traditional brown sauce recipes are based on tomato, but I thought that both the sweetness and texture of apples could stand in for them, particularly when brown sauce is primarily a vehicle for full-flavoured spices. And so came the idea of a making a spiced ketchup where the sweetness and texture of tomato are replaced with those of pumpkin.

Windfall apples in the old orchard

Windfall apples in the old orchard

Historically ketchups were developed from fermented fish-based sauces from the Far East which were brought to the west by the British. In 18th century England they started as dark, savoury table sauces made with mushrooms, anchovies and even walnuts. The development of tomato ketchup took place in America in the early 19th century and this is when recipes for the sauce that we recognise as ketchup today first appeared. Traditional flavourings for tomato ketchup included allspice, mace, ginger, nutmeg and coriander seed. Since all of these, and more, feature in the Moroccan spice mix Ras el Hanout, I decided to use this as the basis of the spicing for this ketchup.

I enjoy the process of making my own spice mixes with a mortar and pestle. The gradual change of texture as the whole seeds and ground spices combine into a fragrant powder is a gratifying experience. You can also balance the proportions of the spices to suit your own tastes rather than relying on a pre-made spice mix which may be a little stale, too heavy on the cloves or cinnamon or lacking the pricier components like mace.

Ras el Hanout

Ras el Hanout

To counteract the sweetness this ketchup needs a good kick of heat. Last year, in keeping with the Moroccan flavourings, I used a combination of harissa and smoked paprika, adding the harissa separately from the spice mix. Earlier this year I was given a large bag of fresh chipotle chilli powder by a friend who had been to Mexico and, since both pumpkin and chilli are native to this part of North America, they seemed a natural pairing. If using ready made Ras el Hanout check that it contains chilli, as some varieties don’t. If so you will need to add the chilli separately.

As with all preserves containing vinegar this ketchup needs to mature before use. However, since the amount used is relatively low in proportion to the other ingredients, it can be used within 2-3 weeks, so there is still time to make a batch for Christmas presents. The flavour improves and develops the longer it is kept.

Use as you would tomato ketchup or brown sauce with fry ups, burgers and sausages, as a marinade for chicken, lamb and pork, or as a seasoning for soups and stews.

Ingredients

1.5kg pumpkin

500g cooking or eating apples

500g onion

1 head of garlic or 7 large cloves

Zest of 1 lemon

3 teaspoons salt

250ml apple cider vinegar

250 g soft brown sugar

Water

RAS EL HANOUT

1/2 teaspoon fennel seed

1/2 teaspoon cumin seed

1/2 teaspoon ground ginger

1/2 teaspoon coriander seed

1/2 teaspoon ground allspice

1/2 teaspoon ground turmeric

1/2 teaspoon ground cinnamon

1/2 teaspoon freshly grated nutmeg

1/2 teaspoon ground mace – 3 blades

1/4 teaspoon ground cloves – about 10 cloves

1/4 teaspoon cardamon seed – contents of about 5 pods

2 teaspoons chilli flakes, smoked paprika, chipotle chilli or harissa

OR

6 teaspoons of ready made Ras el Hanout

Method

Cut the pumpkins in half. Scoop out the seeds and peel, removing any parts that are soft. Chop into pieces and put into a large preserving pan with the peeled, cored and chopped apples, coarsely chopped onion and peeled, trimmed garlic cloves.

Any parts of the pumpkin that are soft or starting to rot are removed

Any parts of the pumpkin that are soft or starting to rot are removed

Lightly toast the fennel, cumin, coriander and cardamom seeds in a small frying pan. Put with the remaining spices into a mortar and pestle or spice mill and grind to a fine powder. Add to the pan with all of the remaining ingredients, apart from the vinegar and sugar. Pour in just enough water to initially prevent the vegetables from catching. They will produce plenty of liquid as they start to cook.

Put the pan over a moderate heat. Cover and cook gently, stirring from time to time, until the vegetables are soft and broken up. Pass the cooked vegetables through a food mill, or process to a smooth puree with a stick blender.

Add the sugar and vinegar and return the pan to a high heat. Cook, stirring continuously, until the mixture thickens. The sauce has a tendency to splutter, so it is advisable to use an oven glove or wrap your hand in a tea towel while stirring. The type of pumpkin you use will determine how much water is given up during cooking. You want to boil it until you have a homogenous sauce with no liquid separated from the solids. The consistency should be a little looser than you want it on the plate, as it continues to thicken as it cools after bottling.

Using a funnel pour into sterilised, heated glass bottles or jars with rubber seals and vinegar-proof lids. Close immediately.

Once cold label and store in a cool, dark place. It will keep for a year or longer.

Makes about four 500ml bottles.

Recipe & photographs: Huw Morgan

The leaves are nearly all down in the wood, winter light fallen to the floor for the first time in half a year. A new horizon meets us as we look out from the house. Not onto the weight of the poplars and their understory, but through to the slopes beyond. The tracery of branches clearly identifying one tree’s character from the next, the tilt of trunks, the hug of shining ivy.

Everywhere the scale change is remarkable and we find ourselves drawn out into the landscape with refreshed curiosity. Much of this is simply to do with a season’s growth dropping back into dormancy. Under the elderly field maple in the clearing by the stream a coppery skirt lies in a circle where the leaves fell in the still air there. Looking up into the newly naked branches a world of lichens and moss – grey, silver and green – has made them home. The nettles that just a month ago were lush and keeping us from the stream have half their volume. With continued frosts in the hollow they will be nothing but brittle stem in a month and we will be free to walk its length once again.

Lichen and moss on the old field maple

Lichen and moss on the old field maple

The stream is audible from up by the house in all but the driest weeks, but now it is charged with winter rain and the noise pulls us down to look. You can easily lose an hour or more if you start to explore the mud and shingle banks, as the stream landscape is always changing. A log from higher up, driven down by storm water, causing damming and silting up, contrasts with the constancy of a favourite boulder, marooned in a pool of its own influence, a home to moss and liverworts.

The moss-covered boulder

The moss-covered boulder

Although the stream is small and at times hidden, it is a favourite part of the property. Soon after moving here at about this time of year we started bank clearance and every year we have done a little more. A barbed wire fence that ran its length to keep the animals in the fields is all but removed now, the rusty coils disentangled and pulled free of the undergrowth and the rotten fence posts removed. As a reminder a number of oak posts that outlived the softwood ones were left to mark the old fence-line. They are now cloaked in emerald moss and, when working in the hollows, are perches for watchful robins.

In places the stream disappeared into a thicket of bramble to emerge again lower down without revealing its journey. The child in me had to know what lay within and the mounds of bramble that bridged the banks were cleared to reveal, in one case, a lovely bend and, in another, a pretty fall and outlook where I have planted a small Katsura grove. I have plans to make a shelter there for watching the water when the trees are grown up, but for now it is simply enough to have the plan in mind as a potential project.

The matted root plate of a mature alder holds the stream bank

The matted root plate of a mature alder holds the stream bank

Slowly, and in tandem with the clearances, I have started to plant the banks on our side where the farmer had taken the grazing right to the very edges. Although we do not want to lose the stream behind trees for its entire length, it is good to balance the volume of our neighbour’s wood on the other side and, in places, to protect the banks. The new trees, just sapling whips at the moment, have been planted so that we can weave in and out of their trunks on the walk up or down the stream and with or against the flow.

Tree planting is one of my favourite winter tasks. The young whips are ordered in the autumn and are with us from the nursery not long after the leaves are down when the lifting season starts. If I can I like to get them all in before the end of the year so that their feeding roots are up and running by the spring when top growth resumes.

Three year old alders on the stream bank

Three year old alders on the stream bank

Alder whips protected from deer with cylindrical tree guards

Alder whips protected from deer with cylindrical tree guards

Alder (Alnus glutinosa), a riverine species that likes to dip its feet into the water, is one of the best for stablilising the banks. The roots, which produce their own nitrogen and charge young trees with vigour, are dense and mat together to form a secure edge where the banks are crumbling from having no more than pasture to hold them together. The deer that have a run in the woods have loved the young growth so, after a year of grazing which left them depleted, I have resorted to using more than spiral guards to protect them. The cylindrical guards are not pretty to look at, but give the saplings long enough to jump up above the grazing line and gain their independence.

Alder catkins

Alder catkins

Alder leaf buds

Alder leaf buds

In the deeper shade of the overhanging wood, and where the alders have proven to be less successful, I have used our native hornbeam (Carpinus betulus), encouraged by a mature specimen that, together with an oak, teeters on the water’s edge. It too has a dense root system and loves the heavy clay soil on the banks that lead to the water. Both the Carpinus and the Alnus have good catkins, which are in evidence already on the alders. Purple-brown and already tightly clustered, with hazel they are the first to let you know that things are already on the move in early winter. The alder buds are also violet and your eye is pleased for the colour which is intense in the mutedness of December. The keys of the mature hornbeam are still hanging in there and glow russet in the slanting sun that makes its way down the wooded slopes.

The trunk of the oak on the opposite stream bank

The trunk of the oak on the opposite stream bank

Hornbeam whips on the stream slope with the mature hornbeam beyond

Hornbeam whips on the stream slope with the mature hornbeam beyond

Keys on the mature hornbeam

Keys on the mature hornbeam

After winter rains the stream rushes in a torrent that would sweep you away if you tried to wade across it, so this winter the stream work will turn to the bridges. Firstly to clear the remains of a stately oak that fell under the weight of its June foliage and then on to repair the clapper bridge that we made a couple of years ago and which was washed away in the heavy rains just recently. For now the fallen poplars, with their perilously mossy trunks, provide the link to the wood from which they fell. One came down the first summer we were here, and another two years later. Now the fallen oak has changed the stream once again and with it our winter diversions.

The fallen oak

The fallen oak

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 2 January 2017

We always grow too many pumpkins. Such has been the luxury of having the space to do so. They have found themselves in a different position every year to give them the opportunity to reach. In the first summer they were in the virgin ground where we had turned field over to garden and the flush of weeds that had been disturbed by the change were kept in check by their coverage. The next year they were out in front of the house, each plant perched on a barrowload of muck on the banks. But it was too exposed there, we had a wet summer and learned their limits, for they made not much more than leaf. The disappointment of not having them in storage lasted the whole winter. Consequently, as the best way to learn is by your mistakes, I have taken their needs more seriously.

Six summers’ worth of trial, error and experimentation have taught us the good producers, the best keepers and those that under-produce in relation to their enormous appetite for space. A Californian friend and gardener, who grows the giant pumpkins you only find in the country where everything is bigger, was amazed that I was giving my plants so little room to grow. His pumpkin patch is the size of my whole garden, so he was not surprised that I hadn’t done better in terms of size and yield. A big plant with a rangy nature can easily take over a plot of nine or more square metres to provide the optimum ratio of leaf to fruit and, now that I have started planting up the garden, space for pumpkins is becoming more limited. So next year’s selection is due an edit. The giants will be separated from those that are happy with less space and the neater, more economical growers will have a bed to themselves in the kitchen garden with plenty of muck and sunshine. The big growers will be given the top of this year’s compost heap so that they can enjoy a romp and tumble over the edges unencumbered.

‘Musquée de Provence’

‘Musquée de Provence’

Of the big growers that produce more leaf than fruit, we will not be growing ‘Musquée de Provence’ again, after three years of trying. The deep-green, lobed fruit, though handsome, are supposed to ripen to a rich tan colour, but even on our south-facing slopes we just don’t have enough sun to do so. Consequently, the skin doesn’t cure fully and they have been poor keepers. Our average of one fruit per plant is also not worth the investment of space. Although a single pumpkin can easily feed twelve, there are only so many times you require a pumpkin that large.

‘Rouge Vif d’Étampes’

‘Rouge Vif d’Étampes’

‘Crown Prince’

‘Crown Prince’

We have had a similar experience this year with ‘Rouge Vif d’Étampes’, another French variety with large fruits of a strong red-orange. It also appears to need more heat to crop heavily and ripen fully. These two have been the first to be eaten, as we try and keep pace with the rot. All pumpkins and squash like heat and good living and our cool, damp climate sorts out those that are clearly missing the Americas. In contrast, ‘Crown Prince’ has been more adaptable here and one of the best croppers for a plant that needs space. It is also an excellent keeper. The saffron flesh is firm and sweet while the thick, grey-green skin means that they can keep into March in a cool, frost-free shed.

The varieties with dry, firm flesh are better for storing than the wetter ones, which I presume is due to their higher sugar content. We also prefer them for eating. Of the smaller growing varieties we have found the Japanese pumpkins to be the most consistent, with the highest yield for their economical growth and the most delicious flesh. They produce fruit of a moderate size, which is far more convenient to eat than opening up a Cinderella-sized pumpkin that feeds a horde and then sits on the side, the remainder unused, making you feel guilty.

‘Uchiki Kuri’

‘Uchiki Kuri’

Of the Japanese varieties ‘Uchiki Kuri’, or the red onion squash, is the one you see most often in Japan and the one I will eat on an autumn visit to Hokkaido where it is grown extensively. It is a moderate grower, with smallish foliage and an even and reliable yield, with each plant producing 8 or more 1-2kg pumpkins. The deep orange teardrop-shaped fruit are small enough to provide for one family meal and, with a good balance of flesh to seed, there is little waste. Kuri means chestnut in Japanese, and the flavour and texture of this and the other kuri varieties explains why. They are excellent baked, with a rich, floury texture that also makes superlative mash and soup with plenty of body.

‘Cha-cha’

‘Cha-cha’

Kabocha is the Japanese word for pumpkin, derived from the corruption of the Portugese name for them, Cambodia abóbora, since they were brought to Japan from Cambodia by the Portugese in the 16th century. This year we grew ‘Cha-cha’, which closely resembles ‘Blue Kuri’, a Japanese kabocha variety we have previously had success with. It has also proven to be very good. Slightly larger than ‘Uchiki Kuri’ the flesh is also dry, rich and sweet, and the thin skin is edible when roasted.

‘Black Futsu’

‘Black Futsu’

‘Black Futsu’, another Japanese variety with sweet, nutty flesh, is of a similar size. The fruits are heavily ribbed and dark, black-green when picked, quickly developing a heavy grey bloom, beneath which they ripen to a tawny orange. Though beautiful to look at, the ribbing does mean they are more work to cut and peel, but it is a small hardship in terms of yield and substance.

‘Delicata’

‘Delicata’

Another heavy cropper, although not such a good keeper, is ‘Delicata’, also known as the sweet potato squash due to it’s mild, sweet flesh which is moister than the varieties described above. Although kept and eaten as a winter squash ‘Delicata’ is of the summer squash species with a very thin skin (hence its name) and so has a propensity to soften quickly in storage. However, it needs no peeling as the skin is edible, so it has its uses in the earlier part of the season. The beauty of this very decorative variety is its high yield of long, cylindrical fruits (perfect for stuffing) in a range of manageable sizes, some the perfect size for one, which makes it a very practical choice.

Although in the past I have let the first frost strip the summer foliage before harvesting, it is best to remove it by hand in September when the plants have done their growing and there is a little heat left in the sun to do a final ripening. It is best to pick the fruits before they get frosted or they don’t keep well, and care must be taken not to damage the hard, waxy skin which keeps them airtight through the winter. The stalks should be left intact for the same reason, as any wound quickly leads to rot.

Left in a warm, sunny place for a couple of weeks after picking the carbohydrates in the flesh turn to sugar and the skin hardens. The colour also changes, but this continues to develop in storage. When ripe they should be stored in a shed or outhouse on wire racks or a bed of straw to allow air to circulate beneath them. For now, I have them on old palettes in an airy barn, but when it gets colder they will be put into perforated plastic plant trays and moved to the frost-free tool shed.

We are gradually making our way through this year’s crop with roast, mash, soup and finally preserves, before the rot sets in. It nearly always does and, although the decay has its own beauty, I’d rather not waste a summer of effort. Both ours and the pumpkins’.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage