There is a point when winter turns and spring takes over. It inches at first, and then that false feeling – that you have time on your hands – begins to evaporate. This year I have been watching for the change more intently than usual, because we had a date in the diary to plant up the first phase of the new garden; the week of the spring equinox which, this year, proved to be perfect timing. One week later and the peonies were already a foot high and the tight fans of leaf on the hemerocallis were flushed and beyond moving without setting them back.

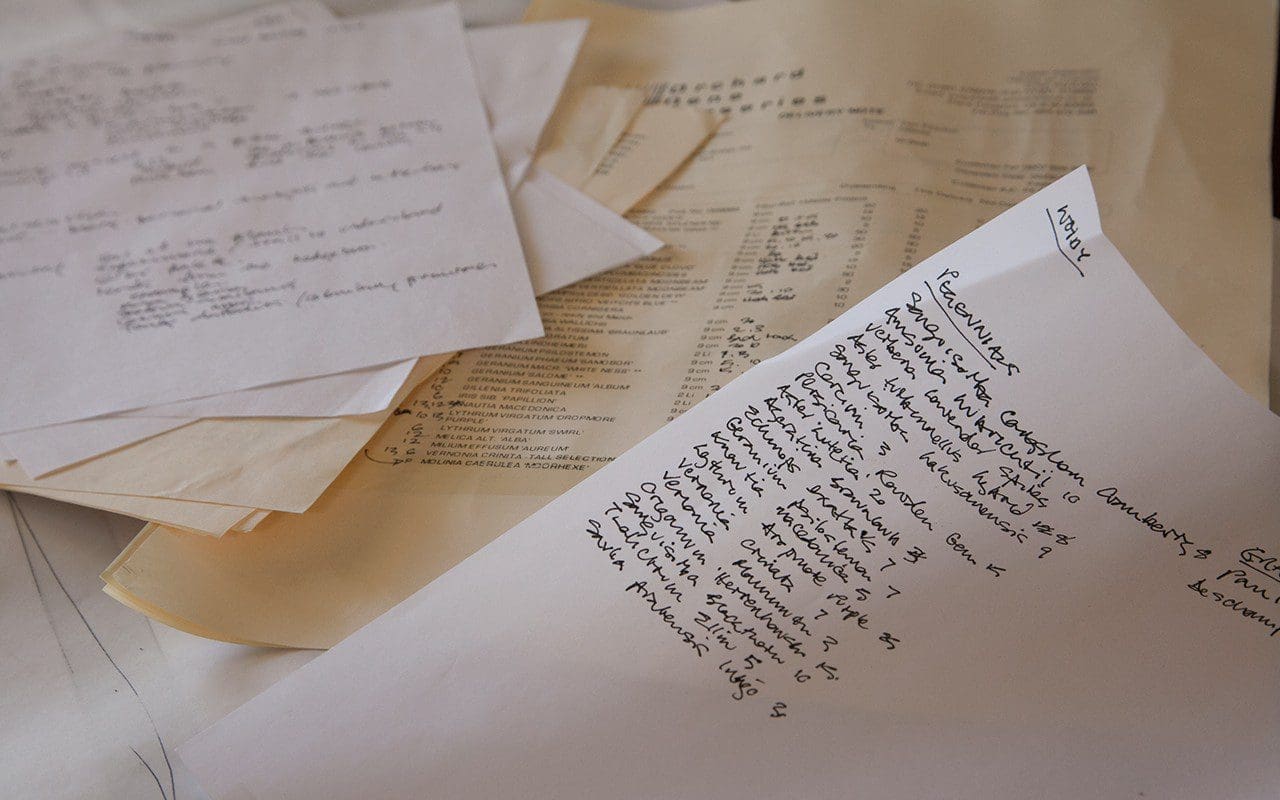

I have been planning for this moment for three years, perhaps longer in refining the idea of the way I wanted the planting to nestle the buildings and blend with the land beyond. I procrastinated over the final plant list for as long as it was possible, but in January it finally went out to the nurseries in time to get the stock I needed for spring.

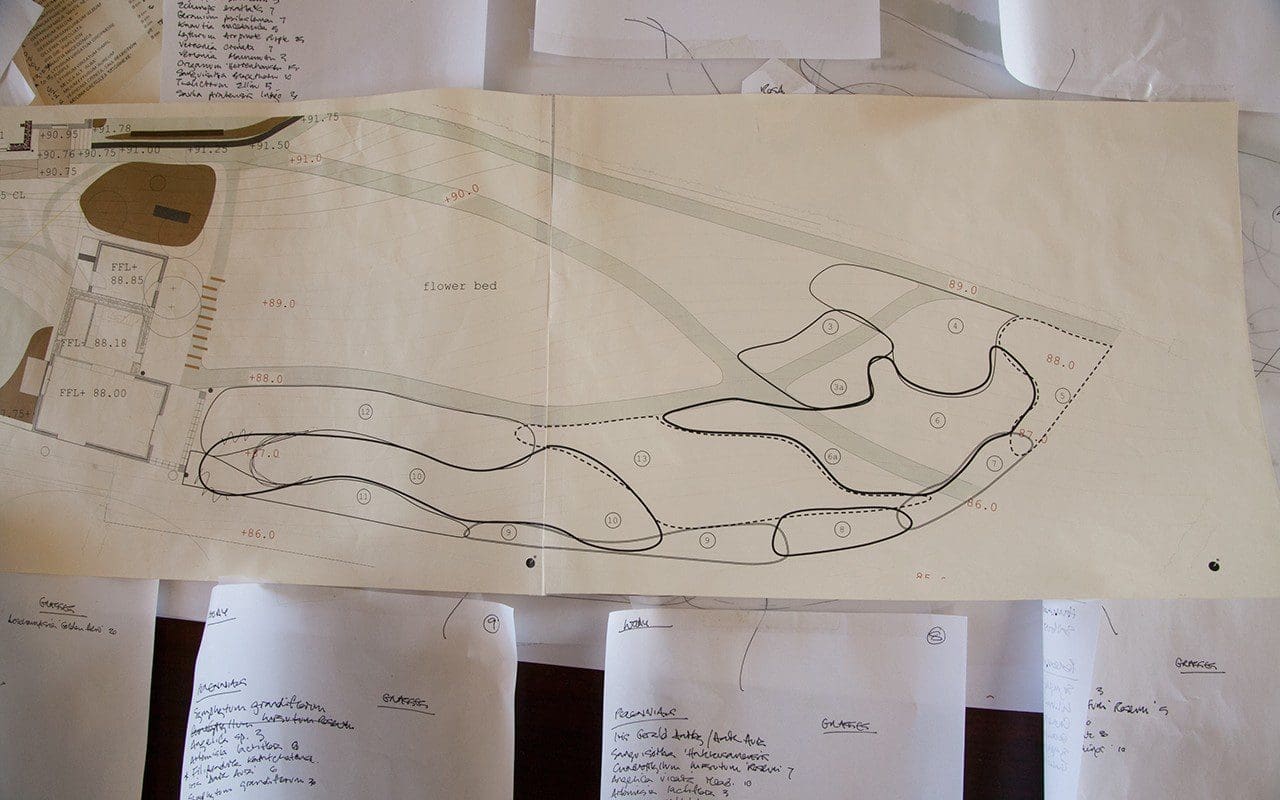

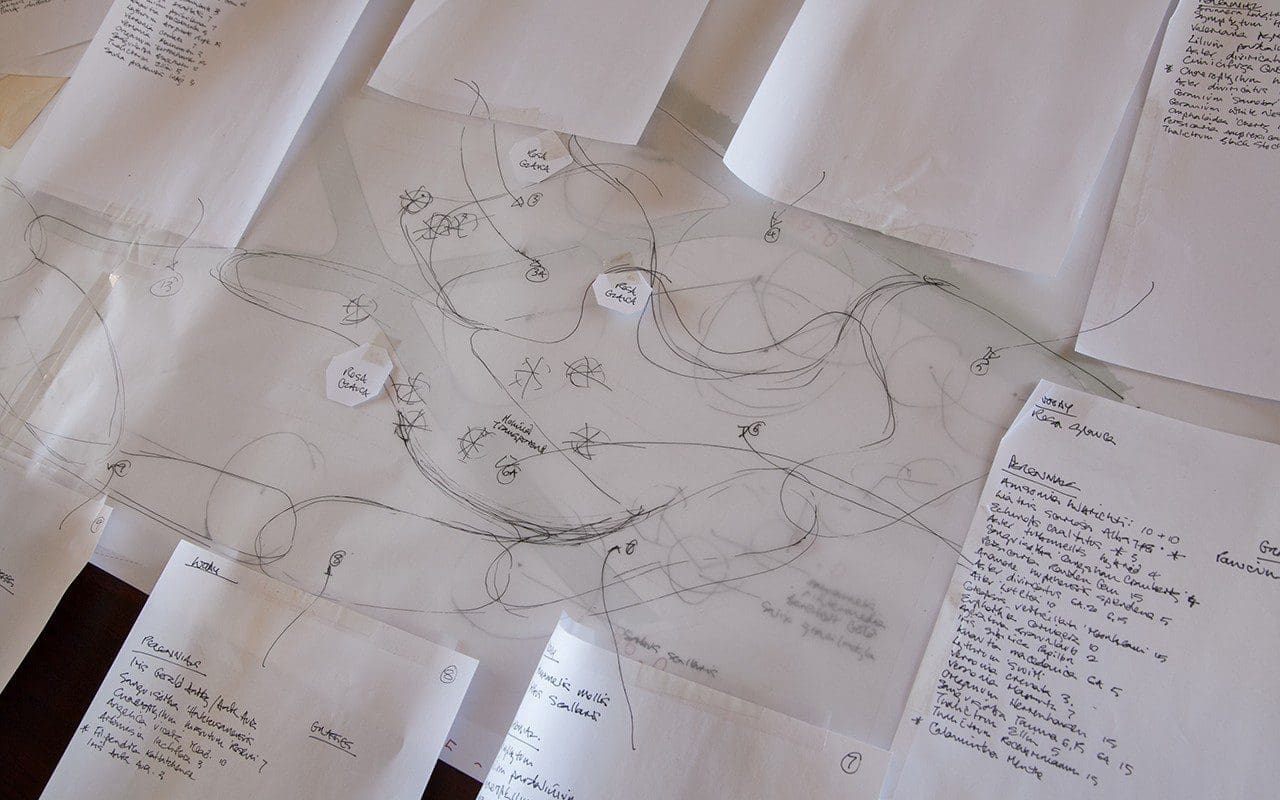

The process of refining a plant palette is one that I know well, but committing a plan to paper is an altogether more difficult thing to do for yourself than for a client. I decided not to make an annotated plan, but instead to map a series of areas that shift in mood as you walk the paths. I paced the space again and again to understand where the ground was most exposed, where it was free-draining and to note that, in the hollow where the ground swung down to the track, there was running water a spit deep this winter. I imagined where I would want height and where I would need the planting to dip, sometimes deep into the beds, to give things breathing space. There would also need to be countermovements across the site, with tall emergent plants brought to the foreground, close to the paths.

The final stages of soil preparation in early March

The final stages of soil preparation in early March

The preparation was completed the week before the plants arrived; the soil dug in the windows when it was dry enough and then knocked out level just in time. We prayed that the weather would dry up, because the soil had lain wet all winter and would not stand footfall if it stayed that way. In tandem with the soil preparation we moved some favourites that I have been bulking up, like the Paeonia mlokosewitschii and Paeonia emodii ‘Late Windflower’, both of which came with us from Peckham, and split those plants that had passed the test in the trial garden. A three year old Sanguisorba ‘Cangshan Cranberry’ was easily divided into eight, and so three plants gave me twenty four to play with; enough to move from bed to bed and to jump the path. The same with the persicarias, the Iris x robusta ‘Dark Aura’, the Aster turbinellus and a long list of others. These were bagged up individually so that I could afford to leave them laid out when shifting the planting around on the day of laying out.

Due to the size of the site this was just the first round of planting, and of only half the garden. The remaining half will be planted this autumn. The plan for this lower half comprises a dozen interlocking areas, which allow my combinations to vary subtly across the site and flow into one another to form a related whole. Before starting, the boundaries were sprayed onto the soil with a landscape marker, although I break these boundaries during setting out, jumping plants across to knit them together.

Shrubs and woody plants were positioned first to articulate the space. Trees by the gates including Hamamelis x intermedia ‘Barmstedt Gold’ and Crataegus coccinea, some Malus transitoria and Rosa glauca breaking in from high up, and home-grown whips of Salix purpurea ‘Nancy Saunders’ and Salix gracilistyla fraying the edges alongside the field. Molinia caerulea ssp. arundinacea ‘Transparent’, the largest of the clump forming grasses, was also given its position early to tie the meeting point of the paths together.

Plan showing the twelve interlocking planting zones

Plan showing the twelve interlocking planting zones

Dan’s hand-drawn zoning plan with developing plant lists

Dan’s hand-drawn zoning plan with developing plant lists

Plant lists and orders

Plant lists and orders

For each of the zones I made a list that quantified all of the plants I would need to make it special. A handful of emergents to rise up tall above the rest; Thalictrum ‘Elin’, Vernonia crinata, sanguisorbas and perpetual angelicas. When laying out these were the first perennials placed to articulate the spaces between the shrubs and key grasses.

Next, the mid-layer beneath them, with the verticals of Veronicastrum virginicum ‘Album’ and Persicaria amplexicaule ‘Rowden Gem’, and the mounding forms of aster (A. divaricatus) or geranium (G. phaeum ‘Samobor’, G. psilostemon and G. ‘Salome’). The plants that will group and contrast. And finally, the layer beneath and between, to flood the gaps and bring it all together. These were a freeform mix; fine Panicum ‘Rehbraun’ with Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Tanna’, or Viola cornuta ‘Alba’, Coreopsis verticillata ‘Moonbeam’ and the white bloody cranesbill, Geranium sanguineum ‘Album’.

The plants arrived from Orchard Dene Nurseries and Arvensis Perennials on the Friday. Immaculate and ready to go and filling up the drive. I like to plant small with nine centimetre pots. If you get the timing right, and don’t have to leave them sitting around, this size is easily trowelled in with minimum soil disturbance. At close spacing this makes planting easier and faster than having to spade in a larger plant.

Plants waiting to be put in position along the paths

Plants waiting to be put in position along the paths

Plants grouped by planting zone

Plants grouped by planting zone

Colour-coded sticks were used to mark the positions of plants yet to be supplied

Colour-coded sticks were used to mark the positions of plants yet to be supplied

It took us two days to complete the lifting and dividing of my stock plants and to set the plants on the paths in their groups. And the process was prolonged as I started adding last minute choices from the stock beds. On the Sunday high winds whistled through the valley to dry the soil, so I started setting out and hoped that the pots didn’t blow into one corner overnight, as once happened in a client’s garden. On the Monday, and ahead of my team of planters who were arriving the next day, I continued to populate the spaces, between the heavens opening up and pouring stair-rods. It was hard, and there was a moment I despaired of us being able to get the plants in the ground at all.

Setting out plants is one of the most all-consuming and taxing activities I know. It feels like it uses every available bit of brain-space. You not only have to retain and visualise the various volumes, cultural requirements and habits of the individual plants, but also the sequencing and rhythm of a planting, how it rises and falls, ebbs and flows, and then how each area of planting relates to the next, in three dimensions and from all angles. Add to this the aesthetic considerations of colour relationships both within and between areas and the time-travel exercise of imagining seasonal changes and there is only so much I can do in one session. However, I was ahead of my planters and, as long as I could hold my concentration once they arrived, it would stay that way with them coming up behind me. The rains abated, the wind continued and the following day the soil was dry enough for planting.

Dan concentrating on plant layout

Dan concentrating on plant layout

Jacky Mills

Jacky Mills

Ian Mannall

Ian Mannall

Ray Pemberton

Ray Pemberton

On the 21st, the sun broke through not long after it was up. A solitary stag silhouetted against the sky looked down on us from the Tump as we readied for the day. Clearly word had already got out that there were going to be rich new pickings in the valley.

Over the course of two days about twelve hundred plants went in the ground. Three people planting and myself managing to stay ahead, moving the plants into position in front of them. Thank you Ian, Jacky and Ray for your hard work, and Huw for supplying a constant supply of necessary vittles.

I cannot tell you – or perhaps I can to those who know this feeling too – what a huge sense of excitement is wrapped up in a new planting. Plans and imaginings, old plants in new combinations, new plants to shift the balance. All that potential. All those as yet unknown surprises.

Already, the space is changed. We will watch and wait and report back.

6 April 2017, two weeks after planting

6 April 2017, two weeks after planting

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Sharp winds have whipped the blossom and pushed and pulled the tender young growth on the epimediums. So often is the way of early April. The cruellest month perhaps but, in its awakening flora, the most exquisite.

Some of my favourite plants are having their moment now. Woodlanders mostly, making the best of bright spring light flooding to the floor ahead of the canopy closing over. The plants that seize this window are ephemeral by nature and you have to steel yourself for not wishing that time would slow. Picking a posy helps to make a close observation of these long-awaited treasures.

Our garden is young and I have just a few square metres of shelter. The pockets close to the studio have to suffice until we gain the protection of new trees and a sliver of shade in the lea of the house is where I keep the Asian epimediums. I have a collection of twenty or so plants, grown against the odds and carefully looked after in pots. I am sure they would perish out in the open, for they are altogether more delicate than their European counterparts, needing a stiller atmosphere and more reliable moisture at the root in the summer.

My efforts to keep them in good condition – namely shelter from wind and trays in the summer to keep the pots moist when I am not here to water – is all the attention they get. Other than picking over the dead foliage in the spring and a monthly liquid feed in summer, they reward me handsomely for this light intervention. Epimedium leptorrhizum ‘Mariko’ was the first to flower. I do not know this plant well yet, but it has flourished for me in the couple of years I have been growing it, forming a neat, low mound of leaf and throwing out charteuse young foliage with delicate red marbling. The large, dancing flowers, held out sideways on wiry stems, are a strong, rose pink with white inner spurs.

Epimedium leptorrhizum ‘Mariko’

Epimedium leptorrhizum ‘Mariko’

Epimedium leptorrhizum ‘Mariko’ foliage

Epimedium leptorrhizum ‘Mariko’ foliage

Epimedium fargesii ‘Pink Constellation’ is much better known to me and the spray in this posy is from the plant I brought with me from my Peckham garden. It is particular in its long, serrated, shield-shaped foliage, which is sharp on the eye yet not to the touch. Three leaflets to a stem and burnished copper when they emerge, they darken to a shiny, holly-green for summer. The flowers, of palest pink, are well named and staccato in appearance, arranged candelabra-like on long, wire-thin stems. They sport dark purple inner spurs and the creamy beak of stamens terminates in unexpected turquoise pollen.

Epimedium fargesii ‘Pink Constellation’

Epimedium fargesii ‘Pink Constellation’

Epimedium fargesii ‘Pink Constellation’ flower detail

Epimedium fargesii ‘Pink Constellation’ flower detail

Epimedium fargesii ‘Pink Constellation’ foliage

Epimedium fargesii ‘Pink Constellation’ foliage

The Vinca major var. oxyloba is altogether more robust and the plant from which these flowers are taken is one I have introduced into the hedgerow alongside the garden. The original came from The Garden Museum and, having seen it take a hold there, the hedge seems like the best place for it. Beth Chatto’s catalogue lists it as having an ‘indefinite spread’ and sure enough it has jumped and moved already, rooting wherever it touches down. Certainly not one for introducing into the garden. A gate to either end of the hedge, a verge and mown path to either side, will kerb its domain, if it ever gets that far. I prefer it to straight Vinca major for it’s finely-rayed, starry flowers, which are an intense inky purple that vibrates in shade. It has been in flower now since late December.

Vinca major var. oxyloba and Corydalis temulifolia ‘Chocolate Stars’

Vinca major var. oxyloba and Corydalis temulifolia ‘Chocolate Stars’

The name of Corydalis temulifolia ‘Chocolate Stars’ refers to the colour of the foliage, which is perhaps its greatest asset, springing to life ahead of everything else with a lushness that is out of kilter with the season. I welcome its luxuriance and have it with the liquorice-leaved Ranunculus ficaria ‘Brazen Hussy’ and my best yellow hellebore, for which it was a good foil early on. I used it at the Chelsea Flower Show a couple of years ago with Vinca major var. oxyloba, amongst cut-leaved brambles on a shady rock bank of Chatsworth gritstone. The pale lilac flowers were nearing the end of the season and it had lost its April vitality which, right now, makes you stop and draw breath.

Fritillaria meleagris

Fritillaria meleagris

This is the second year the snakeshead fritillaries (Fritillaria meleagris) have flowered for us on the banks behind the house. They will not show evidence of seeding for a few years yet but, in the meantime, I will add to the colony to increase its domain in the short turf beneath the crabapples. They are one of my favourite spring flowers, the chequering of the petals more marked on the purple forms, less so but in evidence, green on white, with the albas. They have a medieval quality to them that must have inspired textiles and paintings. And when the wind blows, despite their apparent delicacy, they are oblivious.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

I have just cleared the remains of last year’s growth from the planting around the tin barns (main image). What has not stood the test of the winter westerlies is scattered now, the new rosettes pushing away amongst the tatters. The old stems pull with a satisfying snap and where they resist they are cut to the very base to avoid the sharpened stubs which can catch you out when weeding. Underneath, and vital with spring energy, are the beginnings of new life; a scatter and patterning of seedlings that have found their way and are already asserting their own direction.

What to weed and what to save will be the making of this area come summer. I have deliberately planted the gravel around the barns with a mix of reliably clump-forming perennials, and set amongst them a few wild cards in the form of the self-seeders. The perennials are the bones and will stay put to provide the structure whilst the short-lived perennials and biennials, such as the Verbascum phoeniceum ‘Violetta’, are the colonisers that make it their business to find their niche and so give the area a lived-in look that very quickly feels established.

Seedlings of Verbascum phoeniceum ‘Violetta’

Seedlings of Verbascum phoeniceum ‘Violetta’

Verbascum phoeniceum ‘Violetta’

Verbascum phoeniceum ‘Violetta’

The seeders are part of an experiment, and with any experiment you have to accept both successes and failures. The Erigeron annuus is a beautiful thing in it’s finely-rayed profusion, but they have already proven themselves to be dangerous in this position and will be winkled out now to avoid trouble later. Two plants from the summer before last have already thrown down a multitude of seedlings in any open space that isn’t already taken. I am put in mind of a project I am working on in Shanghai, where they were billowing on the newly turned ground like flotsam and jetsam. They were the pioneers there, the equivalent of fireweed or milk thistle here, and they show no sign of altering their habits. If I were to leave them their apparently light frame would double, treble and bolt to ultimately overwhelm their neighbours.

This might not be the case in another part of the garden, for the crushed concrete that I have used to mulch the bare ground is proving itself to be the perfect seed bed. This is not an issue with those plants that are better behaved. For instance, I would like the crimson Dianthus cruentus to be more prolific in its habits, but it is clear that it likes to live on the edge of a colony of other plants with light and air around it’s basal rosette. Other seedlings have already left the parent behind as their reach has extended into the gravel. A rash of the blue-flowered annual Cephalaria transylvanica has rained beyond last year’s colony and is showing why you only find it listed as an Eastern European arable weed. The difference between a weed and garden plant is made in just half an hour thinning the seedlings so that they do not overpower their neighbours and create the space that will allow the flowers to dance.

Seedlings of Erigeron annuus

Seedlings of Erigeron annuus

Dianthus cruentus

Dianthus cruentus

Seedlings of Cephalaria transylvanica

Seedlings of Cephalaria transylvanica

Cephalaria transylvanica

Cephalaria transylvanica

Orlaya grandiflora, the biennial Bupleurum falcatum and the progeny of last year’s Eryngium giganteum ‘Miss Willmott’s Ghost’ will be given the same treatment, measuring as I weed to leave just enough of each to give the desired effect. It takes time to recognise the tiny seedlings when they first emerge, but once you get your eye in they always have something of the character of the mature plant; the tiny bupleurum seedlings with their lime green cotyledons, almost the exact colour of the umbels, and the fleshy Lunaria annua ‘Corfu Blue’, the first true leaf exactly like that of the parent.

Seedlings of Bupleurum falcatum

Seedlings of Bupleurum falcatum

Seedlings of Eryngium giganteum ‘Miss Wilmott’s Ghost’

Seedlings of Eryngium giganteum ‘Miss Wilmott’s Ghost’

Eryngium giganteum ‘Miss Wilmott’s Ghost’ with Bupleurum falcatum

Eryngium giganteum ‘Miss Wilmott’s Ghost’ with Bupleurum falcatum

It has taken a few years to build the confidence to be so ruthless this early in the season. Too many years misjudging the reach of an apparently harmless rash of Eschscholzia californica seedlings, or a Shirley poppy that didn’t look like it was going to put a dent in the lavender and then did, have taught me my lessons. As you are weeding you have to imagine the scale and bulk of the mature plant and leave a bigger gap than you might like this early. A second pass in two or three weeks time allows room for manoeuvre, so that you can rectify any overcrowding. My third pass is when everything is perfect and just about to lift off in early June. It might leave an uncomfortable gap as you pull the fleshy growth from its hard-won foothold, but to keep the balance takes a little bravery.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

The Blossom Wood was one of my first projects here. Plant trees at the beginning of a project and by the time you have started to round the corner, you have time mapped in growth and your efforts rewarded in the satisfaction of being able to stand in the beginnings of their shadow. Such has been the case here and now, in the sixth spring after planting, we can already walk into the corner of our top field and find a place transformed into the start of somewhere new.

The idea behind the little wood was that it be a sanctuary; for birds, insects, mammals and ourselves. The fields were all but empty when we arrived. You could see from corner to corner and there was no shade other than the fingers borrowed from our neighbour’s trees across the stream. The birds had to hop from hedge to hedge and it was quickly clear that we needed somewhere that they could call home on our side of the stream.

Save the occasional hawthorns that have matured into trees where they have been left in the hedgerows, we all but miss the blossom season and the celebration of spring that comes with it. So all the trees and their associated understorey are native and I have aimed for everything (save a handful of field maples, some spindle and an oak or two) to flower conspicuously and then provide berries for autumn.

The site of the Blossom Wood in 2011

The site of the Blossom Wood in 2011

Planting the whips in January 2012

Planting the whips in January 2012

The Blossom Wood in spring 2016

The Blossom Wood in spring 2016

The Blossom Wood in 2014

The Blossom Wood in 2014

The same view in 2016

The same view in 2016

The cherry plum, Prunus cerasifera (main image), breaks with winter. The buds, pinpricks of hope, swell at snowdrop time. Early on we picked twigs and, now that they are grown, whole branches to bring into the house to force with willow and hazel catkins. After a couple of days in the warmth they pop, pale on dark twiggery and smelling of almonds. Prunus cerasifera is the parent of the Mirabelle plum, which is the first tree to flower in the plum orchard too. It is so worth this early life, which can sometimes appear in the last week of February, but the trees are always billowing by the middle of March.

Rather than the wood erupting all at once the flowering sequence is staggered and broken so that, from the cherry plum now, until June when the wayfaring tree, guelder rose and sweetbriar are flowering, there is always something to visit. If I had left blackthorn in the mix it would be the next to flower, but I removed them after they showed early signs of running. Better to have them in a hedge that can be cut from both sides and where their tiny sprays of creamy flower appear with the most juvenile pinpricks of green on the breaking hawthorn. The hawthorn and the native Cornus sanguinea are fast and have been used as nurse companions to provide shelter to the slower growing species. I want to see how this place evolves unaided, so have decided not to intervene, but I will probably coppice a number to make some more space if I see anything suffering that I need for the long term.

Cherry Plum – Prunus cerasifera

Cherry Plum – Prunus cerasifera

Wayfaring Tree – Viburnum lantana

Wayfaring Tree – Viburnum lantana

Guelder Rose – Viburnum opulus

Guelder Rose – Viburnum opulus

The wild pear, Pyrus pyraster, is a tree I do not know well but have already learned to love. It flowered for the first time last year, a smattering here and there, but I hope for more this spring. Pear flowers are one of the most exquisite of all spring blossoms, the milky flowers, round and ballooning fat in bud and then cupped and beautifully drawn with stamens. The flowers often occur with the very first leaves, lime green and creamy white together. You can see the trees are going to be something. ‘Plant pears for your grandchildren’ they say, for they take time to fruit and go on to live to a very great age. My youngsters, which I planted with all the other trees as whips, are well over twice my height, stocky at the base and showing stamina.

As spring opens up and first foliage flushes, we have wild gean, Prunus avium, to make the transition from leaflessness. The trees are racing up, bolting visibly with each year’s extension growth and already taller than most in the mix. The flowers are fleeting, lasting just half the time of the beautiful double selection ‘Alba Plena’. The wild gean is beautiful though, whirling at the ends of the branches, the flowers are finely held on long pedicels and dance in the breeze. Next comes the bird cherry, Prunus padus, with long sprays of creamy blossom. I have it on the lower, damper ground where it is happiest.

Wild Pear – Pyrus pyraster

Wild Pear – Pyrus pyraster

Wild Gean – Prunus avium

Wild Gean – Prunus avium

Bird Cherry – Prunus padus

Bird Cherry – Prunus padus

Three sorbus follow and come into flower once the wood has flushed with leaf. Rowan (Sorbus aucuparia) with its feathery foliage is planted close to the pears, which will eventually take over. Despite the fact that rowan are said to be long-lived, in my experience, on rich ground and in combination with other species, I have found them to be quick off the mark at first, but affected by the competition later. I wanted to plant whitebeam (Sorbus aria) with the gean because I love the blossom and silveryness of the newly emerging sorbus foliage together. However, now that these trees are maturing and fruiting, I see that I have been mis-supplied with Sorbus x intermedia, a Swedish native. No matter, they are magnificent fruiters, bright scarlet in autumn. The chequer, or wild service, tree (Sorbus torminalis) is the third. Now a very rare tree in the wild, mainly confined to ancient oak and ash woodland, it is a delightful thing, with leaves more like a maple and marble-sized russet fruit that, from medieval times until fairly recently, were bletted and used as dessert fruit (reputed to taste like dates) or to make beer. My young trees are slender and have only just started flowering, but I have a feeling they will become a favourite. I have given them room to fill out and mature without competition.

Rowan – Sorbus aucuparia

Rowan – Sorbus aucuparia

My childhood friend Geraldine left me a few hundred pounds in her will when she died and I put it into planting the wood. A naturalist to the core, I know she would approve of this place which is the domain of wildlife and where the gardener is just a visitor. We find ourselves very much the interlopers here when we visit, disturbing flurries of the birds I’d hoped for, and seeing the tell-tale signs of unseen badgers and of deer seeking cover in the soft beds of grass where I have deliberately left a couple of clearings. I know already that I will be cursing them when they become bolder and find the garden, but it is good to see that, in less than a decade, we have a place that lives up to its name.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

At this time of year there are two major challenges in the kitchen garden; how to use up the remaining winter vegetables in order to clear the beds for the sowing of new crops, and how to bridge the hungry gap, as we reach the end of our stores. Most of the remaining vegetables have been sitting in the ground or in storage for the best part of five months and as the days start to lengthen and warm, we crave the flavours of spring.

The trick to bridging the gap is to combine these winter vegetables with fresher, spring ingredients; roast beetroot with fresh horseradish and watercress, or a plate of sautéed carrots with blood oranges and the last cobnuts.

This recipe is an adaptation of one I usually make with purple sprouting broccoli. However, ours has been a disappointment this year as we sowed a couple of weeks too late and the plants failed to gain enough stature before the winter. The cavolo nero would also have done better with a fortnight more of summer. Although we’ve harvested a few good helpings of leaves we have learned not to uproot it too early, since we have found it has a second season and has been shooting furiously for the past few weeks as it readies itself to flower. The young cavolo shoots are best before all the energy goes into the flower so pick when you see the first buds to retain the velvety texture of the young growth. At the end of winter it has has a mineral richness, which is a good partner to the wild garlic that is now showing itself down by the stream.

Gnocchi are quick and easy to make yourself and a great way to use up the last of the potatoes. It is best to use a floury variety or the gnocchi will be gluey, but I made do with ‘Roseval’, the last of our stored potatoes, which is somewhat waxy. As long as you rice the potatoes while piping hot they still lose a lot of their moisture.

Served with a sharply dressed salad of bitter leaves this makes a perfect spring lunch.

INGREDIENTS

GNOCCHI

500g potatoes, preferably a floury variety like Desirée

1 large or 2 small organic egg yolks

75g Tipo 00 pasta flour

50g semolina

35g (a small handful) wild garlic leaves, finely chopped

Salt

TO SERVE

250g ricotta

100g cavolo nero shoots or purple sprouting broccoli

Olive oil

Pecorino cheese, finely grated

Serves 4 or 6 as a starter

METHOD

To make the gnocchi cook the potatoes in their skins in a large pan of boiling water. Drain and peel them while still hot. Protect your hand with a tea towel or oven glove. Immediately put them through a potato ricer or mouli into a large mixing bowl. Add the egg yolk, flour, semolina, wild garlic and salt and fold through with a metal spoon until well combined. Using very light movements use your hands to quickly bring the dough together into a ball. Do not knead it or the gnocchi will be heavy.

Divide the dough into four. On a floured worktop roll the first quarter into a sausage a little thicker than your index finger, then cut into 2cm pieces with a sharp knife. Take each piece and, pushing away from you, roll them on the back of a fork to create ridges which will hold some of the sauce. Place them on a floured tray. Repeat with all of the dough.

Bring two large pans of generously salted water to the boil. In the first one cook the gnocchi in batches. They are done when they float to the surface. Remove with a slotted spoon and drain them on a clean tea towel while you cook the rest.

As you cook the last batch of gnocchi put the cavolo nero shoots in the other pan of boiling water for two minutes. They should retain some bite. Drain, refresh in cold water and drain again. If using purple sprouting broccoli remove the small florets from the larger stems and cut any larger florets in half or quarters.

Put the gnocchi and cavolo nero shoots into a bowl. Add the ricotta in spoonfuls. Season with salt, ground pepper and a little olive oil. Stir gently to coat adding a little reserved cooking water to loosen if necessary.

Divide the gnocchi between hot plates. Drizzle with olive oil and finish with grated pecorino.

Recipe & Photography: Huw Morgan

Yellow breaks with winter. Soft catkins streaming in the hazel. Brightly gold and blinking celandines studding the sunny banks. They are shiny and light reflecting and open with spring sunshine. As strong as any colour we have seen for weeks and welcome for it.

There is more to come, and in rapid succession, now that spring is with us. The first primroses in the hollows and dandelions pressed tight in grass that is rapidly flushing. Daffodils in their hosts, pumping up the volume and forsythia, of course, at which point I begin to question the colour, for yellow has to be handled carefully.

Lesser Celandine – Ranunculus ficaria

Lesser Celandine – Ranunculus ficaria

In all my years of designing it is always yellow that clients most often have difficulty with. ‘I really don’t like it’. ‘I don’t want to see it in the garden’. ‘Only in very small amounts’. Strong language which points to the fact that it prompts a reaction. Colour theory suggests the yellow wavelength is relatively long and essentially stimulating. The stimulus being emotional and one that is optimistic, making it the strongest colour psychologically. Yellow is said to be a colour of confidence, self-esteem and emotional strength. It is a colour that is both friendly and creative, but too much of it, or the wrong shade, can make you queasy, depressed or even turn you mad.

Whether I entirely believe in the thinking is a moot point, but I have found it to be true that yellow is a positive force when used judiciously. My first border as a teenager was yellow. I experimented with quantity and quality and by contrasting it with magenta and purple, it’s opposites. Today I weave it throughout the garden, using it for its ability to break with melancholy; a flash of Welsh poppy amongst ferns or a carefully selected greenish-yellow hellebore lighting a shaded corner.

Helleborus x hybridus Ashwood Selection Primrose Shades Spotted

Helleborus x hybridus Ashwood Selection Primrose Shades Spotted

I remember talking to the textile designer, Susan Collier, about the use of yellow in her garden in Stockwell. She had repeated the tall, sulphur-yellow Thalictrum flavum ssp. glaucum throughout the planting and explained how she used it to draw the eye through the garden. ‘Yellow in textile design is extraordinarily persistent. It is noisy, but it lifts the heart. It causes the eye to wander, as the eye always returns to yellow.’

At this time of year, I am happy to see it, but prefer yellow in dashes and dots and smatterings. I will use Cornus mas, the Cornelian cherry, rather than forsythia, and have planted a little grove that will arch over the ditch in time and mingle with a stand of hazel. The fattening buds broke a fortnight ago, just as the hazel was losing its freshness. Ultimately, over time, my widely spaced shrubs will grow to the size of a hawthorn, the cadmium yellow flowers, more stamen than petal, creating a spangled cage of colour, rather than the airless weight of gold you get with forsythia.

We have started splitting the primroses along the ditch too. I hope they will colonise the ground beneath the Cornus mas. I have a hundred of the Tenby daffodil, our native Narcissus obvallaris, to scatter amongst them. The flowers are gold, but they are small and nicely proportioned. Used in small quantity and widely spaced to avoid an obvious flare, they will bring the yellow of the cornus to earth.

Narcissus obvallaris with Cornus mas (Cornelian cherry)

Narcissus obvallaris with Cornus mas (Cornelian cherry)

Primrose – Primula vulgaris

Primrose – Primula vulgaris

After several years of experimenting with narcissus, I have found that they are always best when used lightly and with the stronger yellows used as highlights amongst those that are paler. N. bulbocodium ‘Spoirot’, a delightful pale hoop-petticoat daffodil is first to flower here and a firm favourite. I have grown them in pans this year to verify the variety, but will plant them on the steep bank in front of the house where, next spring, they will tremble in the westerly winds.

Narcissus bulbocodium ‘Spoirot’

Narcissus bulbocodium ‘Spoirot’

The very first of the Narcissus x odorus and Narcissus pallidiflorus are also out today, braving a week of overcast skies and cold rain. The N. pallidiflorus were a gift from Beth Chatto. She had been gifted them in turn by Cedric Morris, who had collected the bulbs on one of his expeditions to Europe. The flowers are a pale, primrose yellow, the trumpet slightly darker, and are distinguished by the fact that they face joyously upwards, unlike their downward-facing cousins.

Narcissus x odorus

Narcissus x odorus

Narcissus pallidiflorus

Narcissus pallidiflorus

Our other native daffodil Narcissus pseudonarcissus has a trumpet the same gold as N. obvallaris, but with petals the pale lemon hue of N. pallidiflorus. It has an altogether lighter feeling than many of the named hybrids for this gradation of colour. We were thrilled to see a huge wild colony of them in the woods last weekend, spilling from high up on the banks, the mother colony scattering her offspring in little satellites. This is how they look best, in stops and starts and concentrations. I am slowly planting drifts along the stream edge and up through a new hazel coppice that will be useful in the future. A move that feels right for now, with all the energy and awakening of this new season.

Narcissus pseudonarcissus (top), Narcissus obvallaris (bottom)

Narcissus pseudonarcissus (top), Narcissus obvallaris (bottom)

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Not long after moving here, Jane, our friend and neighbour, took us for a walk into the woods in a nearby valley to see the green hellebore. We pulled off the lane and set off on foot along a well-worn way up into the trees. The north-facing slope had an inherent chill that set it apart from our south-facing slopes and the tree trunks and every stationary object were marked with a sheath of emerald moss.

The track made its way up steeply into ancient coppice. Land too steep to farm and questionably accessible even for sheep. Fallen trunks from a previous age and splays of untended hazels marked the decades that the land had been left to go wild. At least wild in the way that nowhere is truly wild on our little island of managed land. I knew the woods, for we had been here before in summer to look at the fields of orchids that colonise the open grassland above, where the hill flattens out into fenced paddocks. The woods are not extensive, but large enough to have their own environment in this steep fold in the land.

Somewhere near the top of the hill, with the light from the field above us just visible through the tangle of limbs, we set off sideways onto the slopes. The angle was steep enough not to have to bend too far to steady yourself with your hands, but consequently required a firm foothold when inching along the contour. Deep into the trees we came upon our goal. Nestled in under the roots of ancient coppiced hazel and up and out with the very first catkins, the Helleborus viridis.

A wild colony of green hellebore in the local woods

A wild colony of green hellebore in the local woods

To find a plant growing in the wild where it has found it’s niche is to truly understand its habits and requirements. Dry descriptions of habitats and associations in books instantly give way to a greater knowledge, for you never forget when you see a plant looking right in its place. In the cool of the north-facing slope and shaded not only by the deciduous canopy above, but also by the bole of the hazel and its influence, the hellebore was at home. With no competition to speak of, protected by damp leaf mould and with its roots firmly holding in the limestone of the hill, it was king of its place. New foliage, soft and emerald green, splayed fingers of early life. The nodding flowers, concealing the stamens, held free of the ground foliage on arching stems. Viridis, meaning green, is the colour of all its parts; a welcome one at the end of a long winter and a sure sign that the season is ebbing.

Several weeks later I returned in search of seed. The woods were flushed with first leaf which darkened the slopes. Nettles, already fringing the woodland edge where the light penetrated alongside the path, were ready to sting. But deep where the hellebores were growing, they were still in glorious isolation with little more than a few celandine and wood anemone for company. The flowers were transformed, the lanterns replaced by a rosette of bladders which were just turning from green to brown. I cupped my hand underneath and tapped. A slick trickle of ebony seed settled into the crease of my palm.

Green hellebore – Helleborus viridis ssp. occidentalis

Green hellebore – Helleborus viridis ssp. occidentalis

The seed of plants in the family Ranunculaceae is famously short-lived so I sowed it on the same day it was harvested, covered with grit and put in a shady place out of harm’s way. Three seasons later, the following March, it germinated with some success. I kept it in the shade on the north side of the house to throw its first leaves without disturbance. A year later I had seedlings that were ready to pot up and a year after that, to plant out. Jane took a number of the seedlings to start a colony on the north-facing wooded slopes that run up from our shared boundary, the stream. I planted the banks on our side, where the tree canopy provides the shelter, summer shade and leaf litter they need to do well. This year they are flowering for the first time in earnest and, with luck, will set seed and start spreading.

Though they were once used for their purgative qualities (as a folk remedy for worms and the topical treatment of warts), Gilbert White pointed to the fact that it is toxic in all its parts. ‘Where it killed not the patient, it would certainly kill the worms; but the worst of it is, it will sometimes kill both.’ With this in mind, I have kept it away from the sheep and have noted that, even down by the stream where the deer have their run, it remains completely untouched despite its lush, early growth.

One of the young seed grown green hellebores down by the stream

One of the young seed grown green hellebores down by the stream

Though rare in limestone woods in southern England, it is more common in parts of mainland Europe*. Cedric Morris found them in the Picos de Europa growing with a dark form of Erythronium dens-canis; a companion planting it would be hard to emulate here, because of the rush of growth that happens after snowmelt when everything comes at the same time. Its demure nature does not make it a match for the Lenten roses I have here in the garden, which feel rather opulent in comparison. However, I like it very much for its earliness, for its modest break with winter and particularly for the fact that it is native. Where my plants are establishing themselves amongst the newly emerging Arum italicum and an occasional primrose I find great excitement in the thought that spring is now unstoppable.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

A coppiced hazel protected from deer by a cage of offcuts

A coppiced hazel protected from deer by a cage of offcuts

Hazel poles harvested from the hedgerows

Though we complain here about the winter’s duration, I cannot help but compare these few fairly benign months to the harsh conditions at my project in Hokkaido. There the gardeners have to leave the frozen landscape in search of work whilst the garden lies beneath deep snow until late April. The rush of tasks to either side – in preparation for the slumber and then the great surge of activity in spring – is palpable in head gardener Midori’s communications. Meanwhile, here we are free to dig and prune and plant. What luxury it is to get things in order with these few weeks of down time on our hands.

Hazel poles harvested from the hedgerows

Though we complain here about the winter’s duration, I cannot help but compare these few fairly benign months to the harsh conditions at my project in Hokkaido. There the gardeners have to leave the frozen landscape in search of work whilst the garden lies beneath deep snow until late April. The rush of tasks to either side – in preparation for the slumber and then the great surge of activity in spring – is palpable in head gardener Midori’s communications. Meanwhile, here we are free to dig and prune and plant. What luxury it is to get things in order with these few weeks of down time on our hands.

The Meadow Garden at the Tokachi Millennium Forest in Hokkaido is under snow until late April. Photograph: Syogo Oizumi

It has been a busy winter for I am readying myself to plant up the first sections of the new garden that was landscaped last summer. This time last year the same ground lay fallow with a green manure crop protecting it from the leaching effect of rain and to keep it ‘clean’ from the cold season weeds that colonise whenever there is a window of growing opportunity. The winter rye grew thick and lush, except where the diggers had tracked over the ground during the previous summer’s building works, where it grew sickly and thinly, indicating that something needed addressing before going any further.

When we started the winter dig, the problem that the rye had mapped became clear. Not far beneath the surface the soil had become anaerobic, starved of air by the compaction and with the tell-tale foetid smell as you turned it. The organic matter in the soil had turned grey where the bacteria were unable to function without oxygen and the water ran off and not through as it should. Turned roughly at the front end of winter, like a ploughed field, the frost has since teased and broken this layer down and the air has made its way back into the topsoil to keep it alive and functioning. Though it is still too wet to walk across, you can see that the winter freeze and thaw has worked its magic and that, as soon as we have a dry spell, it will knock out nicely like a good crumble mix, in readiness for planting.

The Meadow Garden at the Tokachi Millennium Forest in Hokkaido is under snow until late April. Photograph: Syogo Oizumi

It has been a busy winter for I am readying myself to plant up the first sections of the new garden that was landscaped last summer. This time last year the same ground lay fallow with a green manure crop protecting it from the leaching effect of rain and to keep it ‘clean’ from the cold season weeds that colonise whenever there is a window of growing opportunity. The winter rye grew thick and lush, except where the diggers had tracked over the ground during the previous summer’s building works, where it grew sickly and thinly, indicating that something needed addressing before going any further.

When we started the winter dig, the problem that the rye had mapped became clear. Not far beneath the surface the soil had become anaerobic, starved of air by the compaction and with the tell-tale foetid smell as you turned it. The organic matter in the soil had turned grey where the bacteria were unable to function without oxygen and the water ran off and not through as it should. Turned roughly at the front end of winter, like a ploughed field, the frost has since teased and broken this layer down and the air has made its way back into the topsoil to keep it alive and functioning. Though it is still too wet to walk across, you can see that the winter freeze and thaw has worked its magic and that, as soon as we have a dry spell, it will knock out nicely like a good crumble mix, in readiness for planting.

Digging over the compacted soil, working from boards to prevent further compaction

Time taken in preparation is never time wasted and it is a good feeling to give new plants the best possible start in their new positions. As the soil was previously pasture and we have the advantage of heartiness, the organic content is already good enough, so we will not be digging in compost this year. I want the plants to grow lean and strong so that they can cope with the openness and exposure of the site rather than be overly cosseted or encouraged to grow too fast and fleshy. Organic matter will slowly be introduced after planting in the form of a weed-free compost mulch to keep the germinating weeds down and to protect the soil from desiccation. The earthworms, which are now free to travel through the previously compacted ground, will pull the mulch into the soil and do the work for me.

Digging over the compacted soil, working from boards to prevent further compaction

Time taken in preparation is never time wasted and it is a good feeling to give new plants the best possible start in their new positions. As the soil was previously pasture and we have the advantage of heartiness, the organic content is already good enough, so we will not be digging in compost this year. I want the plants to grow lean and strong so that they can cope with the openness and exposure of the site rather than be overly cosseted or encouraged to grow too fast and fleshy. Organic matter will slowly be introduced after planting in the form of a weed-free compost mulch to keep the germinating weeds down and to protect the soil from desiccation. The earthworms, which are now free to travel through the previously compacted ground, will pull the mulch into the soil and do the work for me.

One of the planting beds in the new garden half dug over to allow the frost to do its work

In the vegetable beds, where we have been working the soil and demanding more from it, the organic matter is replenished annually to keep the fertility levels up. Our own home made compost is dug in now that the heaps are up and running. The compost is left a whole year to break down so that one bay is quietly rotting whilst the other is being filled. If I had more time, or a forklift to turn it, I would have a better, more friable compost in just six months. Turning allows air into the heap and the uncomposted material moved to the centre heats the heap more efficiently to help to kill weed seeds.

One of the planting beds in the new garden half dug over to allow the frost to do its work

In the vegetable beds, where we have been working the soil and demanding more from it, the organic matter is replenished annually to keep the fertility levels up. Our own home made compost is dug in now that the heaps are up and running. The compost is left a whole year to break down so that one bay is quietly rotting whilst the other is being filled. If I had more time, or a forklift to turn it, I would have a better, more friable compost in just six months. Turning allows air into the heap and the uncomposted material moved to the centre heats the heap more efficiently to help to kill weed seeds.

One of the compost bays

My year old compost is only really good for turning in as it springs a fine crop of seedlings from the hay we rake off the banks in the summer. There are also rashes of garden plants; euphorbias that were thrown on the heap after their heads were cut in seed, bronze fennel, Shirley poppies, phacelia and a host of other plants that have lain dormant. No matter. Since the heaps sit directly on the earth the compost is full of worms, and this can only be good for the soil and its future aeration. You can see the soil in the garden getting better and darker, more friable and more retentive with every year that passes. A reward for the hard work and payback for the bounty that we take from it.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan I first encountered wintersweet on a memorable day in the long overgrown wilderness of my childhood garden. Miss Joy, the maker of that acre which had finally overwhelmed her, had clearly been quite a plantswoman and we unearthed many hidden treasures as we cleared forty years of neglect. We had found a colony of trillium surviving in the leaf mould beneath a fallen amelanchier and scarlet peonies pushing through a glade of dim nettle. On this still winter’s day we discovered the wintersweet.

We were slowly freeing the orchard of bramble to make a clearing. The source of a spicy and pervasive perfume eluded us while we worked but, as we cleared deeper into the thicket, we became aware of its origin. Scent triggers the strongest memories and I remember quite clearly the cut and the pull and getting closer to the prize as we tore at the thicket that surrounded and mounted the limbs of the mysterious shrub. Being the most nimble, and with the light of the day failing, the last few feet required a contortion to reach an accessible limb and pull a twig of flowers, which were hardly visible in the half-light, pallid and speckled on the gaunt branches.

I know the smell in an instant now, but then its strength on the cool air was intoxicating for the discovery of something new. Later, in the heat of the kitchen, the perfume from this single twig filled the entire room. Geraldine, our neighbour and my gardening friend from across the lane, shared in the excitement and identified it as Chimonanthus praecox. We studied the waxiness of the translucent blooms. Starry, but cupped like an open hand with fingers facing forward, a second layer revealed an inner boss of petals stained plum-red.

One of the compost bays

My year old compost is only really good for turning in as it springs a fine crop of seedlings from the hay we rake off the banks in the summer. There are also rashes of garden plants; euphorbias that were thrown on the heap after their heads were cut in seed, bronze fennel, Shirley poppies, phacelia and a host of other plants that have lain dormant. No matter. Since the heaps sit directly on the earth the compost is full of worms, and this can only be good for the soil and its future aeration. You can see the soil in the garden getting better and darker, more friable and more retentive with every year that passes. A reward for the hard work and payback for the bounty that we take from it.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan I first encountered wintersweet on a memorable day in the long overgrown wilderness of my childhood garden. Miss Joy, the maker of that acre which had finally overwhelmed her, had clearly been quite a plantswoman and we unearthed many hidden treasures as we cleared forty years of neglect. We had found a colony of trillium surviving in the leaf mould beneath a fallen amelanchier and scarlet peonies pushing through a glade of dim nettle. On this still winter’s day we discovered the wintersweet.

We were slowly freeing the orchard of bramble to make a clearing. The source of a spicy and pervasive perfume eluded us while we worked but, as we cleared deeper into the thicket, we became aware of its origin. Scent triggers the strongest memories and I remember quite clearly the cut and the pull and getting closer to the prize as we tore at the thicket that surrounded and mounted the limbs of the mysterious shrub. Being the most nimble, and with the light of the day failing, the last few feet required a contortion to reach an accessible limb and pull a twig of flowers, which were hardly visible in the half-light, pallid and speckled on the gaunt branches.

I know the smell in an instant now, but then its strength on the cool air was intoxicating for the discovery of something new. Later, in the heat of the kitchen, the perfume from this single twig filled the entire room. Geraldine, our neighbour and my gardening friend from across the lane, shared in the excitement and identified it as Chimonanthus praecox. We studied the waxiness of the translucent blooms. Starry, but cupped like an open hand with fingers facing forward, a second layer revealed an inner boss of petals stained plum-red.

Chimonanthus praecox

Until recently I have not had the place to plant one for myself, so I have gone out of my way to find wintersweet a home in clients’ gardens in the knowledge that they too will reap the rewards in January and February. This vicarious pleasure has been lived out fully at a project I am working on in Shanghai where I have designed a series of gardens that seat a number of restored Ming and Qing dynasty merchant’s houses within a forest of ancient camphor trees.

In the process of understanding how to interpret the planting, my research into Chinese gardens revealed that wintersweet was one of the natives used repeatedly in the pared-back palette of auspicious plants. The winter perfume was revered and the dried flowers were used to scent linen much as we use lavender here. Come the summer the long, lime green leaves are also scented when crushed. I have used them throughout the site as free-standing shrubs, placed close to the junction of paths where you are already pausing, but are then halted by the surprise of perfume.

Chimonanthus praecox

Until recently I have not had the place to plant one for myself, so I have gone out of my way to find wintersweet a home in clients’ gardens in the knowledge that they too will reap the rewards in January and February. This vicarious pleasure has been lived out fully at a project I am working on in Shanghai where I have designed a series of gardens that seat a number of restored Ming and Qing dynasty merchant’s houses within a forest of ancient camphor trees.

In the process of understanding how to interpret the planting, my research into Chinese gardens revealed that wintersweet was one of the natives used repeatedly in the pared-back palette of auspicious plants. The winter perfume was revered and the dried flowers were used to scent linen much as we use lavender here. Come the summer the long, lime green leaves are also scented when crushed. I have used them throughout the site as free-standing shrubs, placed close to the junction of paths where you are already pausing, but are then halted by the surprise of perfume.

Chimonanthus praecox at Westonbirt Arboretum

In its native habitat in open woodland Chimonanthus praecox can grow to as much as thirteen metres. In cultivation it forms a nicely branched shrub of three by three metres and, being well-behaved, it has been a mainstay of Chinese gardens for more than 1000 years. It was first introduced to Japan in the late 17th century as a garden plant and then to Britain a century later, arriving at Croome Court in 1766.

If you read up about it, books repeatedly state that it needs the radiated heat of a south or west wall to ripen its wood sufficiently to flower well. The half-radius of Lutyens’ Rotunda at Hestercombe House, where Gertrude Jekyll’s original planting of 1904 still survives, beautifully demonstrates its use as a wall-trained shrub. Indeed, you see it flowering most prolifically on the hottest part of the wall.

As it is hardy to -10°C it is happy out in the open and I have found it to be far more adaptable in this country where not too far north. The specimen at Westonbirt Arboretum, for instance, is flowering well in open woodland, so it is worth breaking the rules if you dare.

Chimonanthus praecox at Westonbirt Arboretum

In its native habitat in open woodland Chimonanthus praecox can grow to as much as thirteen metres. In cultivation it forms a nicely branched shrub of three by three metres and, being well-behaved, it has been a mainstay of Chinese gardens for more than 1000 years. It was first introduced to Japan in the late 17th century as a garden plant and then to Britain a century later, arriving at Croome Court in 1766.

If you read up about it, books repeatedly state that it needs the radiated heat of a south or west wall to ripen its wood sufficiently to flower well. The half-radius of Lutyens’ Rotunda at Hestercombe House, where Gertrude Jekyll’s original planting of 1904 still survives, beautifully demonstrates its use as a wall-trained shrub. Indeed, you see it flowering most prolifically on the hottest part of the wall.

As it is hardy to -10°C it is happy out in the open and I have found it to be far more adaptable in this country where not too far north. The specimen at Westonbirt Arboretum, for instance, is flowering well in open woodland, so it is worth breaking the rules if you dare.

Chimonanthus praecox ‘Luteus’

Grown from seed wintersweet can take up to fifteen years to flower, a containerised plant five or eight after planting, much like a wisteria. As a species Chimonanthus praecox is variable, but there are a small number of named forms commercially available.

In the Winter Garden I designed at Battersea Park (main image) I have used C. p. ‘Luteus’ as a perfumed welcome by the Sun Gate at the garden’s entrance to draw people in. I am not completely sure the plant supplied is the real ‘Luteus’. Although the flowers register a strong beeswax yellow they have a very slight staining to the central boss, which ‘Luteus’ is not supposed to have. ‘Sunburst’ is yellower still, whilst C. p. ‘Grandiflorus’ has a larger, more open flower which is paler and more translucent. A red stain suffusing the central boss is more typical of the species, which is also reputed to be more heavily scented than the above selections, although I’ve never been able to compare them.

Chimonanthus praecox ‘Luteus’

Grown from seed wintersweet can take up to fifteen years to flower, a containerised plant five or eight after planting, much like a wisteria. As a species Chimonanthus praecox is variable, but there are a small number of named forms commercially available.

In the Winter Garden I designed at Battersea Park (main image) I have used C. p. ‘Luteus’ as a perfumed welcome by the Sun Gate at the garden’s entrance to draw people in. I am not completely sure the plant supplied is the real ‘Luteus’. Although the flowers register a strong beeswax yellow they have a very slight staining to the central boss, which ‘Luteus’ is not supposed to have. ‘Sunburst’ is yellower still, whilst C. p. ‘Grandiflorus’ has a larger, more open flower which is paler and more translucent. A red stain suffusing the central boss is more typical of the species, which is also reputed to be more heavily scented than the above selections, although I’ve never been able to compare them.

Planting the new wintersweet at Hillside

As I have waited this long to be able to plant one for myself and am impatient for flower, I went to Karan Junker for a mature, field-grown specimen. Her seed came to her via Roy Lancaster from a batch originally selected by the great Japanese botanist and plant collector Mikinori Ogisu. There is a fabled pinky-red clone in Japan and the seed potentially included these genes. Just before Christmas I planted my ten-year-old by the studio door so that the perfume is not wasted and today it has broken the first of a half dozen buds to reveal a form that is clear waxy yellow. There are no dark markings, but the scent – my February fix and instant reminder of my childhood discovery – is bewitching. A winter without wintersweet would be a duller season, unmarked by this strange, scented treasure.

Planting the new wintersweet at Hillside

As I have waited this long to be able to plant one for myself and am impatient for flower, I went to Karan Junker for a mature, field-grown specimen. Her seed came to her via Roy Lancaster from a batch originally selected by the great Japanese botanist and plant collector Mikinori Ogisu. There is a fabled pinky-red clone in Japan and the seed potentially included these genes. Just before Christmas I planted my ten-year-old by the studio door so that the perfume is not wasted and today it has broken the first of a half dozen buds to reveal a form that is clear waxy yellow. There are no dark markings, but the scent – my February fix and instant reminder of my childhood discovery – is bewitching. A winter without wintersweet would be a duller season, unmarked by this strange, scented treasure.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan We are sorry but the page you are looking

for does not exist.

You could return to the homepage

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan We are sorry but the page you are looking

for does not exist.

You could return to the homepage