One of the goals we set ourselves when we started Dig Delve was for the writing to be as current as possible. A piece on crabapples the week they are in full bloom, a report of a garden visit made just a couple of weeks previously, and recipes using the best from the kitchen garden and hedgerows as they come into season. Many of the pieces are written the day before publication, so this ambition is not without its challenges, since Dan is often travelling for work, we need to have holidays, and sometimes other life events simply have to take precedence.

Dan has been up north this week. Firstly visiting the new RHS Chatsworth Flower Show and then on to Lowther Castle in Cumbria, where they are celebrating their official opening this weekend. So it was down to me to come up with this week’s piece.

However, like most of the country, I was up into the small hours of Friday morning watching the election coverage with bated breath. The consequent late morning start, with the accompanying time required to get a handle on what was happening in parliament, meant that I had to think on my feet to come up with a recipe for today’s issue.

I had originally thought to make a gooseberry and elderflower ice. Whether ice cream or sorbet I hadn’t decided, but, after half an hour Facetiming a friend in New Zealand who had called for an election update, it was clear that I wasn’t going to have the time to faff around with sugar syrups or custards or the freezing required afterwards. I needed something simple and immediate.

Earlier in the week I had got my first batch of elderflower cordial going and it was ready to strain and bottle. I try and make a large batch every year, but have been foiled for the past two by a combination of constant wet weather and being away in June. The recent clear, warm weather meant that, for the first time in a while I have been able to pick enough to be able to replenish our supplies.

It is essential to pick the flowers on a warm day when they are dry, and to only pick the freshest ones that have just opened and are purest in colour. If you live in a city don’t pick flowers near main roads (when we lived in Peckham I used to get my supplies from nearby Nunhead Cemetery). Don’t, whatever you do, wash the flowers, as you will wash away the pollen which gives the drink most of its flavour. For the same reason I don’t even shake the flowers before using, as many recipes suggest. Unless you are squeamish any small insects get strained out prior to bottling.

I can never get enough of the flavour of elderflower. Its floral taste announces summer. Sparkling elderflower cordial is the most refreshing way to slake your thirst during a hot afternoon’s gardening. Although I have found that a scant teaspoon of cider vinegar added to a glass is the most refreshing of all. Like orange blossom’s more demure, earthy cousin elderflower pairs well with any number of fruits, from strawberries to rhubarb, pears, raspberries, grapes and even grapefruit. It also works with gently flavoured vegetables that allow its floral notes to shine. A teaspoon or two of cordial adds fragrancy to a vinaigrette for a white chicory and goats cheese salad. A pickled salad of very finely sliced cucumber macerated in a dressing made with cordial, honey and, again, cider vinegar, and finished with poppy seeds and elderflowers, makes a sophisticated partner for poached trout or salmon.

Yesterday’s time shortage meant that I was thrown back on the reliable combination of elderflower and gooseberry, which crops up in a number of desserts I regularly make, including the unavoidable fool, a green summer pudding and a baked egg custard tart. The gooseberries aren’t quite ripe when the elder blooms, but for this drink you want the refreshing sharpness of the younger fruit.

This celebratory aperitif is a version of a Bellini where peach puree is replaced with gooseberries and a splash of elderflower cordial. I may have only had bad ones, but have always found peach Bellinis to be a little sickly. Here the combination of tart green fruit and scented flower create a drink with a distinct muscat flavour, which is dry, fragrant and deliciously quenching on a hot summer’s day. To ensure the best result, it is vital that everything, including the glasses, is ice cold before you make them.

First is the recipe I use for homemade cordial, but you could use a good quality shop-bought one.

Elderflower Cordial

Ingredients

Makes about 1.5 litres

30 elderflower heads

1kg white sugar

1 litre water

2 lemons, chopped

1 orange, chopped

2 teaspoons citric acid

¼ crushed Campden tablet (optional)

Put the sugar and water in a saucepan and bring to the boil. Stir and ensure the sugar is completely dissolved. Take off the heat and stir in the citric acid until dissolved.

Put the elderflowers and chopped citrus fruit into a sterilised plastic or glass lidded container large enough to take all of the ingredients. Pour over the hot sugar syrup. Put the lid on the container and leave in a cool dark place for 48 – 72 hours.

Strain the cordial through a fine muslin or tea towel that has first been sterilised with boiling water. Finely crush the Campden tablet and add it to the cordial. Stir until dissolved.

Using a funnel pour the cordial into sterilised bottles. Fasten the lid and store in a cool, dark place.

The Campden tablet (potassium or sodium metabisulfite) prevents the cordial from developing wild yeasts and bacteria which would cause it to ferment, and means that it keeps almost indefinitely. If you prefer not to use them the cordial will keep for 2-3 months, or longer if refrigerated.

Gooseberry ‘Hinnomaki Green’

Gooseberry ‘Hinnomaki Green’

Gooseberry & Elderflower Bellini

Ingredients

Makes 6

100g green gooseberries

Elderflower cordial, chilled

1 bottle dry prosecco

Put the gooseberries in a saucepan with a splash of water. Put the lid on and cook over a low heat for about 10 minutes until the fruit has completely collapsed and given up its juice. Press the fruit through a sieve. You should have about 80ml of purée. Discard the seeds and skin. Put the purée into a covered container, then into the fridge until well chilled.

To make the drinks, take six champagne flutes or narrow tumblers that have been in the freezer for at least twenty minutes. Put two teaspoons of gooseberry purée and two teaspoons of elderflower cordial in the bottom of each glass. Slowly top up with very cold prosecco.

Decorate with a few elderflowers and raise a toast!

Recipe and photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 10 June 2017

Everything is different after rain. The new plantings in the garden went without for almost a month. Sitting tight and not moving. I kept a close eye and watered just once to help them break into the new ground without becoming reliant. The ground opened up with cracks wide enough to put your fingers into and the fields dulled when, at this turning point from spring to summer, they are usually luminous.

Then a fortnight ago, and just in time, the heavens opened. Wetting deep and gently and flushing thirsty growth, which responded overnight with a new vivacity. Only rain has that effect, the growth transformed with a charge and vitality that can only be described as a post-coital glow. The metaphor ends there but, true to say, we are now surrounded with the surge of new vigour, which has touched everywhere and everything, save the wild garlic in the woods, which is receding now in its counter-movement.

Most dramatic was the response in the meadows, which kicked into growth. The camassias, twinkling above the grass, were soon left behind and the little yard beneath the banks in front of the house vanished from view. I seeded the newly graded slopes last September, casting down a St. Catherine’s mix from the valley next door, and adding to it with some sheaves of the wild barley that we collected in Greece a few years ago. I wanted to see if it would cope with the conditions and, to date, it is the first delight in the mix.

We first saw the barley (Hordeum bulbosum) growing by the side of the road on an early April trip to the Dodecanese. It was at exactly this point of growth then, rising up above the last of the spring flowers and shining in the first heat in the sun. The feathered seedheads were swaying in the wind and I was enchanted by its languorous movement. I have always found plants that harness the wind to be captivating and immediately saw it on our breezy hillside.

Friends who live on the island harvested some seed and sent it in the post. It was sown immediately that autumn and bulked up rapidly over the winter to be ready for the spring and then complete its life cycle before the drought of summer. Here, my concern was that it would not be able to cope with as much water as we get in England, but it has shown me to be wrong, flowering heartily in its first summer and proving to be perennial these last four years. The species name refers to the bulbous swellings, the size of an onion set, at or just below ground level. These storage organs keep the parent plant going when seedlings fail in a drought year in the Mediterranean, where it is one of the most common perennial grass species.

The original plants are dwindling now in their fourth summer, but they have seeded freely. Although the seedlings are easy to pull and have not been problematic in an easy to tend strip of ground, I would not want to let them loose in a perennial planting unless their companions were tough enough to cope with their ability to seize a gap. In the narrow bed in front of the house I have it with Digitalis lutea, Thalictrum flavum ssp. glaucum and early-to-rise bronze fennel. Clump-forming cephalaria and crambe might be good company but, for now, I am trying them in more relaxed company.

Hordeum bulbosum with Digitalis lutea and Thalictrum flavum ssp. glaucum at the front of the house

Hordeum bulbosum with Digitalis lutea and Thalictrum flavum ssp. glaucum at the front of the house

So it looks like their new home, in the containment of our hottest steepest, most freely draining bank, might be a good one. We will see if they can cope with our native grasses which, as they establish, may outcompete them when they are no longer the pioneers. I will let them run to seed again and see how they perform. If they dwindle, the seed is easily collected and may make a nice component to an autumn sown hardy annual mix of eschscholzia, white corncockle and orlaya. An experiment perhaps, if this one is just fugitive, but I’ll find a reason to make sure that this hypnotic beauty is always with us somewhere to celebrate the first weeks of summer.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs & Film: Huw Morgan

Published 3 June 2017

The word on the street was that this year’s Chelsea Flower Show was a little lacklustre, suffering somewhat from the late withdrawal of a number of show garden sponsors. However, the show always has something to delight at if you look hard enough.

Although there are increasingly fewer of them, the specialist nurseries in the Great Pavilion show what real, impassioned horticulture is all about. I always head there first, notebook in hand, to find the treasures that might inspire a new planting, or add an extra something to an established scheme. It is impossible to resist some of the plants on display and, as I place orders for later delivery, I visualise the changes the new arrivals will make with excitement.

A handful of the show gardens caught my attention this year but, despite the reduced number, there were several which repaid closer viewing. I made notes on a number of new plants and well-considered combinations. These are some of the things that caught my eye.

I’m on a slightly unstoppable peony roll at the moment and, as well as ordering some tenuifolia hybrids, I hankered after these from Binny Plants.

Paeonia ‘Mahogany’

Paeonia ‘Mahogany’

Paeonia ‘Claire de Lune’ & Paeonia ‘Buckeye Belle’

Paeonia ‘Claire de Lune’ & Paeonia ‘Buckeye Belle’

Paeonia ‘Pink Hawaiian Coral’

Paeonia ‘Pink Hawaiian Coral’

And these from Kelways.

Paeonia ‘Blaze’

Paeonia ‘Blaze’

Paeonia ‘Roman Gold’

Paeonia ‘Roman Gold’

I always seek out Kevock Garden Plants, who supplied a huge number of the tangerine Primula ‘Inverewe’ that was one of the stars of my last Chelsea show garden. The delicacy and perfection of their display never fails to render me speechless. A garden fairyland that takes me right back to my childhood. Stella Rankin, one of the owners, told me that this year they had a new helper with a background in floristry set up the stand, and there were some sophisticated and bold colour combinations.

Primula florindae and Meconopsis Lingholm’

Primula florindae and Meconopsis Lingholm’

Meconopsis ‘Lingholm’

Meconopsis ‘Lingholm’

Primula japonica ‘Postford White’

Primula japonica ‘Postford White’

Semiaquilegia adoxoides

Semiaquilegia adoxoides

Corydalis calcicola

Corydalis calcicola

I also spotted these beauties on a nearby stand but, to my annoyance, forgot to note down which one.

Meconopsis baileyi ‘Alba’

Meconopsis baileyi ‘Alba’

Lupinus lepidus

Lupinus lepidus

Kniphofia pauciflora

Kniphofia pauciflora

There is usually at least one variety of foxglove on The Botanic Nursery stand (main image) that catches my eye, and this year was no exception.

Digitalis purpurea ‘Apricot’

Digitalis purpurea ‘Apricot’

Digitalis ‘Primrose Carousel’

Digitalis ‘Primrose Carousel’

Digitalis ‘Polkadot Pippa’

Digitalis ‘Polkadot Pippa’

Digitalis cariensis

Digitalis cariensis

And on the Harperley Hall Nurseries stand this one stood out.

Digitalis ‘Illumination Raspberry’

Digitalis ‘Illumination Raspberry’

In spite of our south-facing hillside site I can never resist the woodlanders, and have been planting for shade so that I can have just a few of my favourites. I am slowly building a collection of martagon lilies and so never miss a lengthy exploration of the Jacques Amand stand, my notebook quickly filling with new varieties I want to get to know better.

Lilium martagon ‘Arabian Night’

Lilium martagon ‘Arabian Night’

Lilium martagon ‘Claude Shride’

Lilium martagon ‘Claude Shride’

Lilium martagon ‘Sunny Morning’

Lilium martagon ‘Sunny Morning’

Lilium martagon ‘Terrace City’

Lilium martagon ‘Terrace City’

While I really wanted to get my hands on this hybrid lily from H. W. Hyde.

Lilium ‘Garden Society’

Lilium ‘Garden Society’

I have recently made a dry herb planting in the gravel between the house and the kitchen garden, predominantly of lavender, with salvias and a range of umbellifers for pollinators. I was on the lookout for some additions to lift the scheme and, although I already have Allium christophii in the mix, these sculptural alliums from Warmenhoven would definitely add to the feeling of ornamental production I am aiming for.

Allium sativum var. ophioscorodon

Allium sativum var. ophioscorodon

Allium ‘Green Drops’

Allium ‘Green Drops’

Allium scorodoprasum ‘Art’

Allium scorodoprasum ‘Art’

While I thought this thistle would also make a good companion in the gravel.

Galactites tomentosa ‘Alba’

Galactites tomentosa ‘Alba’

From dry plants to aquatics at the Waterside Nursery stand, where I visualised the pond in which I might plant some of these choice specimens.

Typha lugdunensis

Typha lugdunensis

Typha minima

Typha minima

Ranunculus flammula

Ranunculus flammula

Iris pseudacorus ‘Roy Davidson’

Iris pseudacorus ‘Roy Davidson’

Iris versicolor ‘Mysterious Monique’

Iris versicolor ‘Mysterious Monique’

Just as I was leaving the Great Pavilion I chanced across these two clematis on the Thorncroft Clematis stand, which I would love to find homes for.

Clematis mandschurica

Clematis mandschurica

Clematis integrifolia ‘Ozawa’s Blue’

Clematis integrifolia ‘Ozawa’s Blue’

Of the show gardens James Basson’s Best in Show winner grabbed the attention. Bold and confident hard landscaping was colonised by a huge range of native Mediterraneans, whose weedy grace was a great foil for the beautifully detailed, monumental stonework. The rectilinear walls created some carefully framed moments.

Charlotte Harris‘ Gold Medal garden for the Royal Bank of Canada was an exercise in stylish restraint. Inspired by the boreal forests of Canada the space was held by a group of jack pines (Pinus banksiana), which sheltered a graphic pavilion of burnt larch and copper, creating a potent sense of place. In contrast to this evergreen presence the woodland and waterside plantings were transparent and delicate, with some exquisite combinations.

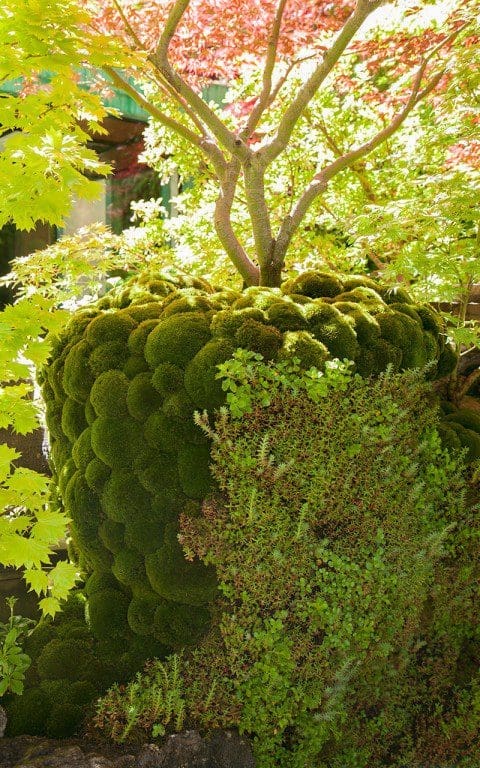

In the Artisan Gardens category the yearly return of Ishihara Kazuyuki is always one to be celebrated. As is the beautifully-crafted way with all things Japanese, the fully-planted, green walls at the side and rear of his ‘Gosho No Niwa’ garden were more magical than the front, conjuring somewhere tranquil and dreamlike

To fill the holes left by some of the show gardens that were withdrawn, Radio 2 produced five Feel Good gardens relating to each of the five senses. Given the exceedingly short time frame of two months in which the designers had to design, source and build these gardens, the standard was extremely high, which made it a shame that they were not included in the judging.

The garden representing sound, designed by James Alexander-Sinclair, was a lush green oasis, punctuated with a staggered series of rusted troughs. Speakers mounted beneath the surface of the water vibrated to create ripples, splashes and gentle undulations depending on the bassline of the song being played.

The Anneka Rice Colour Cutting Garden was designed by Sarah Raven, who had somehow managed, in the time available, to assemble a riotous potager bursting at the seams with her signature jewel-coloured plantings.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 27 May 2017

Nearly all of the vegetable beds in the kitchen garden are now empty of last year’s crops and are gradually being refilled with this year’s. The autumn sown broad beans are 3 feet high, the peas, sown just over a month ago, are twining around their supports, and the first seedlings of lettuce, beetroot and carrot are finally getting away after the long dry spring. The very last of the old veg to come out is the chard. Sown this time last year, eight plants (four of white-stalked Swiss chard and four of the crimson-stemmed ruby chard) have stood all winter, providing some variety of greens amongst the cabbages. For the past three months, the young leaves have been the foundation of our first salads, while the older ones have found their way into a number of chard tarts.

Swiss chard with ruby chard behind

Swiss chard with ruby chard behind

You rarely see Swiss chard in farmer’s markets, and I have never encountered it on a restaurant menu. This is most likely due to the fact that the large fleshy leaves quickly wilt after cutting, giving it an unappealing appearance for sale. Freshly cut, however, they are shiny and juicy and squeak with health as you gather and prepare them. We rarely grow spinach as we have had trouble with even the bolt-resistant varieties. For the amount of time and effort expended in sowing, tending and harvesting, the resulting meagre handfuls we have been able to gather before they go to seed reduce to nothing in the pan and so are hardly worth growing. Chard is far less temperamental and has a much longer growing season.

Although they don’t have as high a concentration of oxalic acid as spinach, and which gives these leafy greens their distinctive ‘dry’ taste in the mouth, I use chard leaves to replace spinach in any recipe that calls for it, and prefer the sweeter, mellower flavour. Chard also has the added benefit of its thick edible stalks, or ribs, for which, in France, they are primarily grown and considered a great delicacy on a par with white asparagus. A completely separate vegetable from the leaf, they are most similar in texture to sea kale and can be used in any recipe that calls either for that uncommon vegetable, white asparagus, cardoons or celery. As you would with cardoons or celery, the stalks must be de-stringed before use, or you will find yourself with an unpalatable, unswallowable mouthful of fibre.

In France it is common to make a gratin of the blanched stalks covered with either a béchamel sauce or, in the south, one made of tomatoes, onion, garlic and olives. The quickest way to prepare them is to cut them into pieces, blanch them for a few minutes, drain and then transfer to a pan in which you have stewed some onion and garlic in olive oil. Leave to cook together, covered, for a few minutes more, then season and serve dressed with lemon juice and chopped parsley.

Sometimes, though, I want to elevate this seemingly mundane ingredient into a dish over which a little more care is taken, and this very slightly adapted recipe from Richard Olney’s Simple French Food, is one I often make. It is incredibly simple, but cooking the stalks in an aromatic court bouillon before combining them with a richly-flavoured, slow-cooked sauce, creates a layering of flavours that causes the vegetable to undergo an almost alchemical transformation during cooking into something that is more than the sum of its parts.

Garlic, anchovy and saffron are much-used ingredients in Provence, where Olney lived and learnt much of his art for French country cooking from Lulu Peyraud, and the taste of this dish is reminiscent of rouille, the saffron and garlic sauce that accompanies bouillabaisse. So, as a side dish, it is a natural pairing with fish.

When serving as a main course I might scatter over a handful of oiled breadcrumbs and some grated Gruyère for the last 10 minutes of cooking, and, as Richard Olney himself recommends, serve with a simple pilaf of onion and tomato.

Remove the fibres from the ribs using your fingernails or the edge of a sharp knife

Remove the fibres from the ribs using your fingernails or the edge of a sharp knife

Ingredients

500g of chard ribs, trimmed and destringed, cut to the length of your gratin dish or into 10cm long pieces

Court Bouillon

2 litres of water

2 banana shallots or 1 large onion, finely sliced

2 bay leaves

A large bunch of thyme

1 tablespoon white wine vinegar

10 black peppercorns, lightly crushed

1 teaspoon of salt

Roux

1 tablespoon olive oil

1 tablespoon plain flour

2 anchovy fillets, ideally the large ones preserved in salt, or 4 of the small fillets in oil

2 large cloves garlic, peeled

A pinch of cayenne pepper, to taste

A pinch of saffron threads, to taste

500 ml of the court bouillon

A small bunch of flat-leaved parsley, leaves removed and chopped

Serves 4 as a side dish, 2 as a main course

Prepared chard stalks

Prepared chard stalks

Method

Put all of the ingredients for the court bouillon into a saucepan and bring slowly to the boil, then simmer gently for half an hour with the lid on. Strain the liquid, discarding the solids, and return it to the cleaned pan.

Bring back to the boil, put in the chard ribs and cook until tender – 10 minutes or a little longer. Remove the ribs with a slotted spoon, allow excess liquid to drain, then transfer them to the gratin dish.

Turn the oven to 230°C.

In a mortar pound together the anchovy, garlic, cayenne and saffron threads until you have a fairly smooth, golden paste.

Anchovy, garlic & saffron paste

Anchovy, garlic & saffron paste

Make the roux by stirring the flour into the olive oil in a small pan, and then cook on a low heat for two minutes, stirring all the time. Add the anchovy, garlic and saffron paste and, still stirring, cook for half a minute more. Off the heat add a couple of spoonfuls of the court bouillon and stir well until smooth. Add the remainder of the court bouillon, stir and return to the heat. Stir continuously until the sauce comes to the boil and begins to thicken. The sauce should be quite thin, so don’t expect it to thicken much. Then leave to simmer on the lowest heat for about 20 minutes. Skim off the skin that forms on the surface as the sauce reduces by about a quarter. It should have the consistency of single cream. Taste and season with salt, no pepper.

Pour the sauce over the chard ribs and put into the oven for 20–30 minutes until bubbling and golden brown at the edges. Scatter the parsley over the top and serve.

Words & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 20 May 2017

The tulips are finally over or, more to the point, we are taking control this weekend and will bring their extraordinary display to a close by lifting the bulbs and clearing the bed. As is the way with Christmas decorations, I feel almost as much pleasure in finally stripping away their ornamentation after the period of illumination and, for a moment, for there to be quiet. And, with the cool, dry weather this year, they have been flowering for a full six weeks.

We started growing tulips in earnest in the garden in Peckham, ordering a handful of varieties to fill the pots on the terraces. Each year, a favourite was kept on to get to know it better and winkled into the beds to see if it would last in the ground. That was how we discovered that we preferred ‘Sapporo’ to ‘White Triumphator’, for the fact that it ages from primrose to ivory, and it has been hard to match the perfume and vibrant tangerine of ‘Ballerina’.

When we moved here we continued to experiment, upping the number of varieties and planting the tulips in rows in the vegetable garden to slowly build an armoury of favoured varieties. As we became more confident with our experimentations and learned how to extend the season by including early, mid and late season tulips, we began a to grow them altogether differently.

Tulipa ‘Sorbet’

Tulipa ‘Sorbet’

Tulipa ‘Sorbet’

Tulipa ‘Sorbet’

Tulipa ‘First Proud’

Tulipa ‘First Proud’

Tulipa ‘Perestroyka’

Tulipa ‘Perestroyka’

I was in the process of planting up a client’s walled garden and, for cutting as much as display, we created a series of mixes to play with the sheer breadth of varieties. We chose colour combinations to conjour a series of moods and colour fields, some dark, some pale or pastel, but always with a top or bottom note of vibrancy or depth to offset the predominating mood. The flowering groups were combined together to lengthen the season so that the early varieties were covered for by the late, and short with tall so that the combinations were layered. We also included differing types – doubles, parrots, flamed, fringed and picotee – for that sweetie box feeling of delight in variety.

At home, this has now become the favoured way of keeping up the experiment. Each year we buy thirty or fifty bulbs of up to eight varieties and dedicate a bed in the kitchen garden exclusively to a spring display. We have moved them from bed to bed to avoid Tulip Fire. Tulips are most prone to the fungal infection when repeatedly grown in the same ground, but rotate on a three or five year cycle and you will diminish the chance of infection. In combination with our thirst to try new varieties, it has also been the reason that, at the end of the season, we discard the bulbs and start again with a new batch for November planting. The bulbs, which are cheap enough to buy in quantity wholesale, are planted late at the end of the bulb planting season. They are debagged and thoroughly mixed on a tarpaulin before being spread evenly on the surface of the bed and winkled in with a trowel a finger’s width apart so that they are not touching.

Three forms of Tulipa ‘Gudoshnik’

Three forms of Tulipa ‘Gudoshnik’

This year we have also started growing the Broken and Breeder tulips from the Hortus Bulborum Foundation. This range of old varieties – some of which date back to the 17th century – fell out of popularity in the 1920’s because, in the main, they are late flowering, and the quest for colour to break with winter began to favour the earlier flowering varieties. Their lateness has been a delight, as they have come just as we have begun to tire of the resilience of the modern tulips. Because they are choice (and expensive) we bought just three or five of each, combining them in pans and planting an individual specimen of each in 5 inch clay pots, so that they could be brought into the house for close observation.

Inside, they last for a week in a cool room and continue to evolve whilst in residence, their more subtle colouring, feathering and breaks filling out and flushing in the maturing process. They feel precious and not disposable like the Dutch tulips, so we plan to try and keep the bulbs when they are over. I will grow them on to feed the bulbs for six weeks after they have flowered, before drying and storing the bulbs in the shed until the autumn. I am hoping they will come to more than just leaf next year.

A mix of Broken and Breeder tulips from Hortus Bulborum

A mix of Broken and Breeder tulips from Hortus Bulborum

Tulipa ‘Absalon’

Tulipa ‘Absalon’

A more subtly marked form of Tulipa ‘Absalon’

A more subtly marked form of Tulipa ‘Absalon’

Tulipa ‘Prince of Wales’

Tulipa ‘Prince of Wales’

Tulipa ‘Lord Stanley’

Tulipa ‘Lord Stanley’

As cut flowers tulips continue to grow, their stems often lengthening as much as a foot or more in a tall-flowered variety such as ‘First Proud’. This has been a new favourite this year, rising up to 90cm; as tall as, but later than, ‘Perestroyka’. A mixed selection of varieties is also good in a bunch and, as they age, the stems arch and lean, sensing each other it seems, so that a vase full will fan out like a firework exploding. The flowers change too, opening and closing with the heat and light and changing colour, sometimes intensifying, sometimes bruising from tone to tone as they fade. The mercurial colour changes are the most interesting and offer far more in terms of value than those that change less, and a new personal favourite this year has been ‘Gudoshnik’, the flowers of which you would swear were different varieties; some are pure vermilion, others red with yellow feathering, others yellow with red streaks. We have also enjoyed the raspberry ripple breaks and freckling of ‘Sorbet’.

If you are experimenting as we are the mixes can be hit or miss, and this year’s wasn’t one of the best, because we didn’t warm to a couple of varieties that have thrown the colour off. We won’t be growing ‘Zurel’ again. The flowers are boxy, the petals stiff and waxy and the flaming is rather coarse. ‘Slawa’ was worth a try, because it looked interesting when we ordered from the catalogue, but it felt too graphic in the mix. The colour combination of peach and plum needs careful placing, and the flowers are less graceful than some. Harsh criticism, perhaps, but a good combination is easily let down by an element that isn’t quite right.

Tulipa ‘Insulinde’

Tulipa ‘Insulinde’

Tulipa ‘Marie-Louise’

Tulipa ‘Marie-Louise’

Tulipa ‘Beauty of Bath’

Tulipa ‘Beauty of Bath’

Tulipa ‘Panorama’

Tulipa ‘Panorama’

Tulipa ‘Royal Sovereign’

Tulipa ‘Royal Sovereign’

The less successful varieties were also shown in a new light by the older varieties. The breaks, feathering and flaming of the Broken tulips, and the rich tones and pastel gradations of the Breeder tulips are altogether more sophisticated. Put side by side the latter are certainly a rather superior race. Not without their problems I’m guessing, because they are less robust in appearance when compared to the modern hybrids. Particular favourites have been ‘Insulinde’, streaked the colours of blackcurrant fool, ‘Marie Louise’, a Breeder of a delicate, graduated lavender pink, ‘Panorama’, a Breeder of a strong copper orange and ‘Absalon’, a Broken tulip (and one of the original Rembrandt tulips) which has ranged from the flamed, blood-red and yellow you see in illustrations to a more subtle mix of mahogany streaked with tan, like an old-fashioned humbug.

Though we have heard much about their growing popularity, seeing them in the flesh has been a little like discovering really good chocolate. I fear we have now been spoiled and it won’t be possible to be without them.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 13 May 2017

I was watching closely this year as the buds on the tree peonies started to swell. My plants needed to be moved from the stock-bed to their final positions in the new garden and it was critical that the timing was right. They have sentimental value, for I collected the originals as seedlings that were springing up under their parents at the Edinburgh Botanic Gardens. I was 19 and working under Ron McBeath, a great adventurer and plant collector in his own right and a man who understood that, if you fell for a plant, it was an all-consuming thing. It was tacitly acknowledged that a certain amount of ‘pockle’ (the term for spare plants for the taking) was tolerated. In fact, I had an orange crate strapped to the back of my bike for such booty. The seedlings were our morning’s weeding so a clutch made their way back to my digs, and then to my parents’ garden, before I was able to take them on to my garden in Peckham a good fifteen years later.

From there they came here as a new generation of seedlings which I’d been growing on just in case. Although they take up to five or six years to flower, growing from seed is easy enough if you sow it fresh as soon as it drops. Germination happens six weeks or so afterwards, but only underground. The first leaves don’t show themselves above ground until the following spring. I left them in the cold frame for a couple of years, as the young roots resent disturbance, and they were lined out here in the stock beds and flowered a couple of years after we moved in. Each plant has subtle differences – the joy of raising from seed – but all are as captivating as the original I now saw thirty-four years ago.

Paeonia delavayi and Smyrnium perfoliatum

Paeonia delavayi and Smyrnium perfoliatum

I have half a dozen Paeonia delavayi in their new positions, stepped through the entrance to the garden from the house to form a gateway of sorts. Although I wasn’t ready to move the plants until the end of winter, they were dug carefully with a decent root-ball to minimise disturbance. The move happened as soon as I saw the buds swelling, so that they would have the energy of growth on their side and not sit and sulk in wet soil.

Read up about moving peonies and most literature says they are hypersensitive and prone to failure and, if you do succeed, they take a long time to establish. It is also recommended to move them in the autumn, so that the early growth is supported by roots which have been active the winter long and can support this early flush of activity. However, my plants have proven all of the above to be rules worth bending.

Growth is famously early, fat buds breaking ahead of almost everything else and making them vulnerable, you might think, to the cruelty of March and April weather. Again, according to the books, you are supposed to plant tree peonies in positions where the early growth isn’t caught by morning sunshine which, in combination with a freeze, is lethal. A slow thaw is better but, miraculously, our plants were all untouched by a vicious frost last week that toasted the Katsura down by the stream and wilted the early growth on the campion in the hedgerow, so I believe them to be tougher than the hybrid Moutan peonies, their more exotic cousins.

Growing in pine clearings in Yunnan and Eastern Asia, Paeonia delavayi is more adaptable than you might first imagine. Edge of woodland conditions suit it best, but here, on our retentive soil, it has been happy out in the open with all-day sun and freely moving air on the slopes to confound best-practice positioning. I do like contradictions and the ever-evolving learning curve when you get to know your plants and their limits.

Standing in glorious isolation, and ahead of the planting which will join them in this part of the garden in the autumn, I am free to admire their form and am imagining their companions; the things that will complement their moody atmosphere and rich colouring when it comes to planting time. Tall, rangy stems, that will eventually reach six foot or so and as much across as they mature, give way to elegantly furling growth at the tips. The flowers, of darkest blood-red and with stiff, waxy petals, appear before the leaves are fully expanded, hanging at a tilt to hide the boss of red-flushed stamens which age to gold. The beautifully dissected foliage is coppery-bronze at this stage with a damson-grey bloom that fades to a matt neutral green as it fills out.

Paeonia potaninii and Smyrnium perfoliatum

Paeonia potaninii and Smyrnium perfoliatum

Paeonia potaninii, which hails from Western China and Tibet and is thought by some to be a subspecies of P. delavayi, is similar in its growth, but differs in its gently suckering habit. My original seedling, still growing in the dappled shade of my parents’ orchard, is now several feet across. It looks happy in the clearing and is competitive enough to deal with the infestation of ground elder and ferns that have made the orchard their territory.

Here conditions couldn’t be more different, but my plants show their adaptability by flowering more profusely and being less lush in leaf out in the open. The flowers are the most extraordinary confection of apricot overlaid with burnt sugar, like shot silk surrounding decorative saffron stamens. The flowers hang heavy amongst the new leaves and cast a strong perfume as you pass on the path. The distinctive scent has something of the citrus spice of witch hazel, but overlaid with an exotic, grassy sweetness. Cut, in a vase, their perfume is more easily savoured.

We have them here with the acid-yellow Smyrnium perfoliatum, which lifts the subtlety of the colour and throws it into relief. I’ll need to do this in the garden too and plan to have the darkness of P. delavayi amongst Anthriscus sylvestris ‘Raven’s Wing’, with P. potaninii floating above the ruby-red droplets of Dicentra formosa ‘Bacchanal’.

Though the brilliance of the Smyrnium is perfectly pitched with these rich, warm colours, I take heed from Beth Chatto’s words when I told her it hadn’t yet taken off in my garden in Peckham. ‘Just you wait !’, she said. And I, not wanting to break all the rules, have remembered her advice and have only set it free on the rough ground behind the barns with the comfrey.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Three years ago, Troy Scott-Smith invited me to become a Garden Advisor for the garden at Sissinghurst. It was a role I was happy to explore, for I have known the garden for years as a visitor, but there is nothing like getting to know a place better from behind the scenes and through the people that work there.

Anyone who owns or gardens a garden knows all too well that feeling of only seeing what needs doing. Sometimes it is hard to focus on the achievements, the long view or to simply take stock and see what is happening in the here and now. My annual meetings with Troy take place in a different season every year, with notebooks and an open brief to walk and talk and ponder. This year I made my visit in late March, a good time to evaluate a garden while the structure is still visible.

A second eye from an outsider is often exactly what is needed and we have cultivated an openness in the discussion, where opinions may count here but not there, and where the shared mission is to get to the essence of things. For me, this is a complete luxury, as I am free of the responsibility I have in my role in the design studio and can look without having to provide more than an honest opinion.

Head Gardener, Troy Scott-Smith

Head Gardener, Troy Scott-Smith

By way of introduction Troy had sent me his manifesto before my first visit. When he applied for the role as Head Gardener he talked openly of the need for change and, to the credit of the National Trust, they employed him to implement this vision. He absolutely did not see this as change for change’s sake, but a means of recapturing the potent sense of place that Vita Sackville-West celebrated in her writing about the garden that she and Harold Nicolson had made at Sissinghurst Castle; a garden inextricably linked to the buildings it surrounded and, in turn, the Kentish farmland and countryside that swept up to its walls.

Troy saw the need for the place to be unlocked again from the rigour that had become the way that people came to know the garden after the death of Vita and Harold in the 1960’s. A challenge perhaps for the most famous garden in the country but, for one with such good bones, a new era of excitement.

The Top Courtyard

The Top Courtyard

Beyond the wall of the Top Courtyard is Delos

Beyond the wall of the Top Courtyard is Delos

The White Garden

The White Garden

The Orchard

The Orchard

The Cottage Garden with topiary yews (left) and the Rondel (right) with the Rose Garden to the right. The Lime Walk can be seen running to the left of the exit at the top of the Rondel.

The Cottage Garden with topiary yews (left) and the Rondel (right) with the Rose Garden to the right. The Lime Walk can be seen running to the left of the exit at the top of the Rondel.

I expect that there are very few good gardens that are the product of one vision. Gardens are places where skills come together and, indeed, where they work in combination to make the whole altogether stronger. Vita and Harold’s relationship was a perfect example. He with his architectural mind providing the structure and she, the romantic, the counterpoint of informality. Her writings talk of a place that was, first and foremost, lived in by its owners and where ideas and experiments did not demand year-round perfection. However, the garden then did not have the pressures it has now with up to 200,000 visitors a year. Mulleins breaking into the paths could be negotiated and roses reaching beyond their allocated space were free to reign.

Vita wrote well about her gardening experiences and possessed a powerful vision, but she was not a professional gardener. She was learning as she evolved the garden and, like all of us, her mistakes and failures were probably as numerous as her successes. Clambering roses overwhelmed the apple trees to bring them down where their vigour wasn’t matched, and some areas of the garden were simply allowed to recede into the background when out of season. There were bold and visionary moves, such as the tapestry of polyanthus in the Nuttery that would ultimately fail to disease and need rethinking.

When the National Trust took over in 1967, five year’s after Vita’s death, an inevitable tightening up eventually saw the garden reach extraordinary horticultural heights in the hands of Pam Schwerdt and Sibylle Kreutzberger who worked with Vita from 1959 until she died, but went on to make the garden their own during their 30 year tenure as joint head gardeners. Pam and Sibylle’s prowess with plants was a large part of what brought visitors to Sissinghurst in their droves in the 1970’s and ’80’s, securing its place as one of the most influential gardens in the world. The way the garden became was ultimately driven by the need to provide for increasing numbers of visitors and, in so doing, the intimate sense of place was slowly and gradually altered.

Troy and Dan in the Lime Walk

Troy and Dan in the Lime Walk

The Lime Walk

The Lime Walk

In the Rose Garden

In the Rose Garden

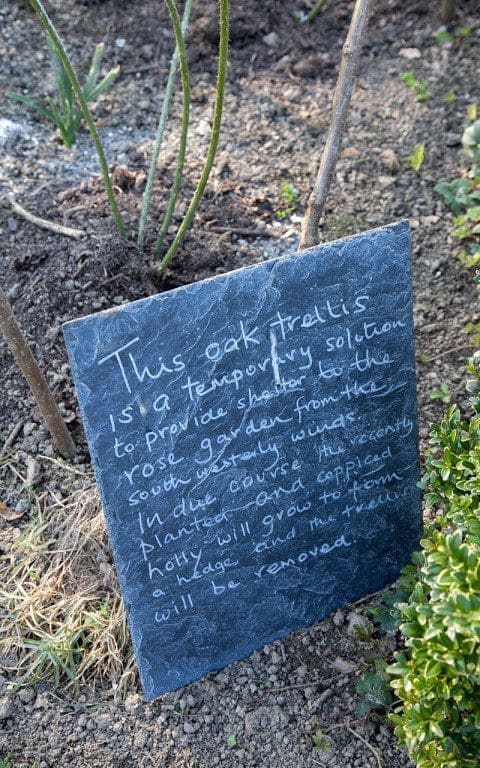

New oak trellis in the Rose Garden

New oak trellis in the Rose Garden

Yew hedges are gradually being reconditioned with hard pruning

Yew hedges are gradually being reconditioned with hard pruning

I have known Sissinghurst since I was a child. My father and I would visit every summer and walk its enclosures with notebooks in hand. I remember very distinctly the feeling of awe and then panic fused with disappointment that we would simply never be able to garden to this level of perfection. So we would drive on determinedly to Great Dixter to take the antidote of a garden living and breathing its owner and not attempting to garden with belt and braces. Even when the blueprint is strong gardens can easily assume a different character, for a garden is really the gardener.

And now Troy is slowly and gently making changes. He has turned the lawns at the approach into meadow and reinstated an old cart pond. There is a new hoggin entrance and there is talk of returning some of the brick and stone paths in the gardens to grass. If they wear, people will be redirected until the grass recovers, to preserve the calm and intimacy of the softer surface.

Roses that were tightly trained against the walls were given a couple of years off to reach away from their constraints. New apple trees have replaced old and the cigar-shaped yews in the Top Courtyard are being allowed to grow out into a looser shape, as they were in Vita’s day. The Little North Garden (formerly the Phlox Garden) was for years made inaccessible from the White Garden after the steps were removed in 1969. It has been reconnected with new steps which will provide another way out when the White Garden is at its peak and crowded. And Troy is planning on re-instating the phlox that once grew there in Vita’s time and after which she named it.

The yews in the Top Courtyard are being allowed to grow out into a looser shape as they were in Vita’s day

The yews in the Top Courtyard are being allowed to grow out into a looser shape as they were in Vita’s day

Discussing Troy’s planting plans for the Little North Garden. The new stone steps lead up to the White Garden.

Discussing Troy’s planting plans for the Little North Garden. The new stone steps lead up to the White Garden.

The White Garden. The Little North Garden is reached through the arch in the boundary wall.

Dan and Troy discuss recent new additions to the White Garden

Dan and Troy discuss recent new additions to the White Garden

A newly planted olive in the White Garden

A newly planted olive in the White Garden

For years the Kentish Weald was the driving force and counterpoint to the formality of the garden and its enclosures, so we have talked of taking pressure off the garden and of making it less introverted, opening it up again to the land around it. The Nuttery has been enlarged, with new coppice hazels, a softer secondary path and a permeable fence boundary to the fields beyond. By removing the later addition of the hedge along the Nuttery, the field and the lake it flanks instantly provide a visual decompression. There is now talk of allowing people into the meadow and down to the lake so that, when the garden is busy, it provides an overspill area. After many years without them, Troy is also planning to reinstate Vita’s massed plantings of polyanthus in some areas.

The Nuttery

The Nuttery

Original stone path in the Nuttery

Original stone path in the Nuttery

New soft path in the Nuttery, with additional coppice hazel and visually permeable split chestnut fencing

New soft path in the Nuttery, with additional coppice hazel and visually permeable split chestnut fencing

Last year, Joshua Sparkes, one of the enthusiastic young gardeners working with Troy, won a scholarship to visit Delos, the inspiration for one of the garden areas that has lost its way. Vita and Harold had been inspired by the Greek island and had strewn the area beyond the Top Courtyard with a small number of artefacts and stone walls to conjure a Greek hillside. Facing north and with exposure to the winds from across the fields, the site was not the ideal place to try such an experiment.

Later incarnations saw the garden protected on the windward side with a hedge of Pemberton roses and a canopy of magnolias took over to provide more shade, which subsequently saw the garden become home to primarily woodland plants. However, Troy has a little grove of cork oaks waiting in the nursery and Joshua’s research has identified a number of Greek natives to bring out the spirit of the place again. It may not be exactly as Vita and Harold had intended, but they wouldn’t have stood still either. As gardeners I have the feeling they would have embraced change and all the excitement and energy that comes with it.

Delos

Delos

Spring planting in Delos

Spring planting in Delos

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

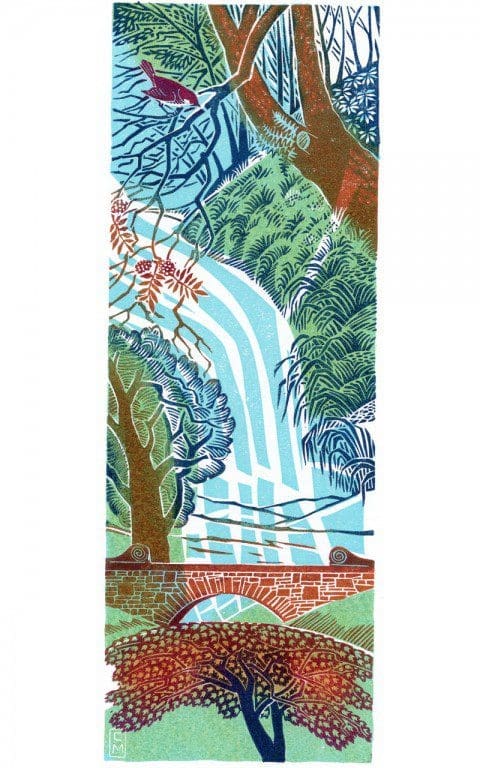

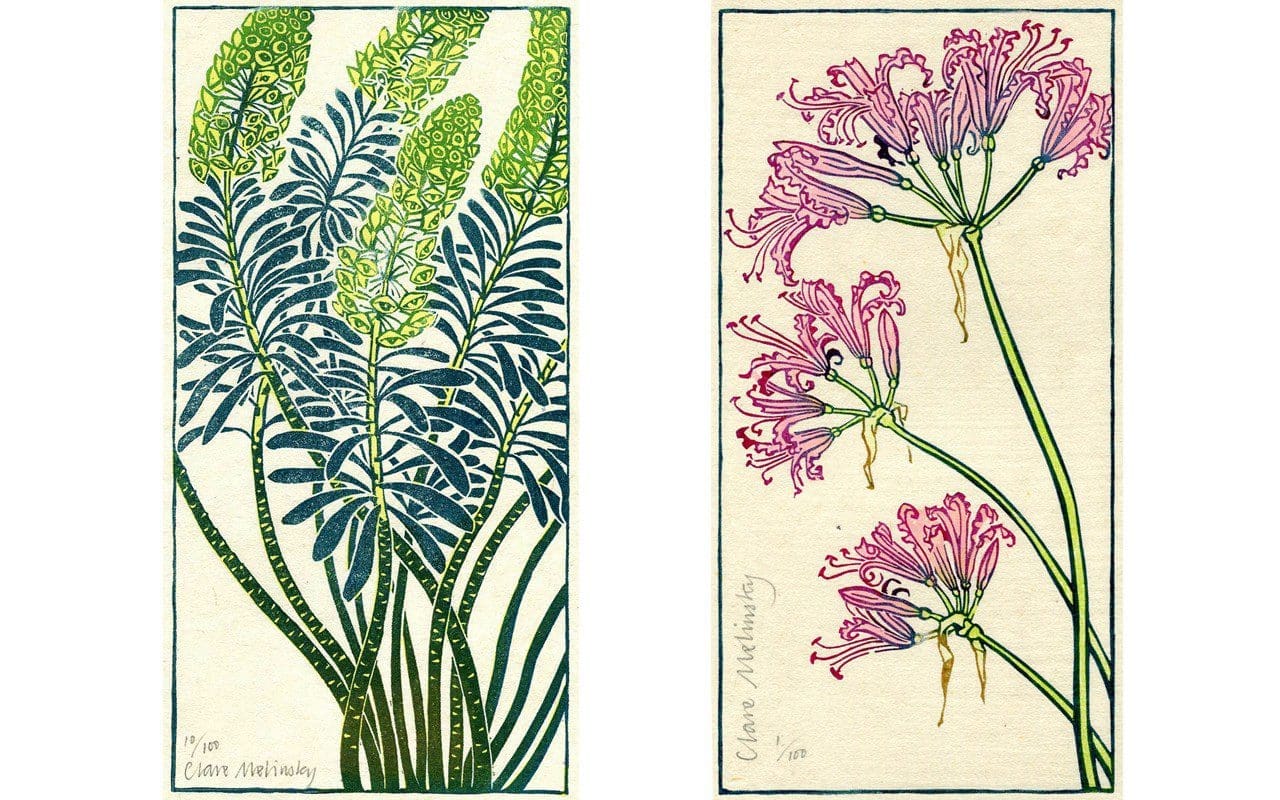

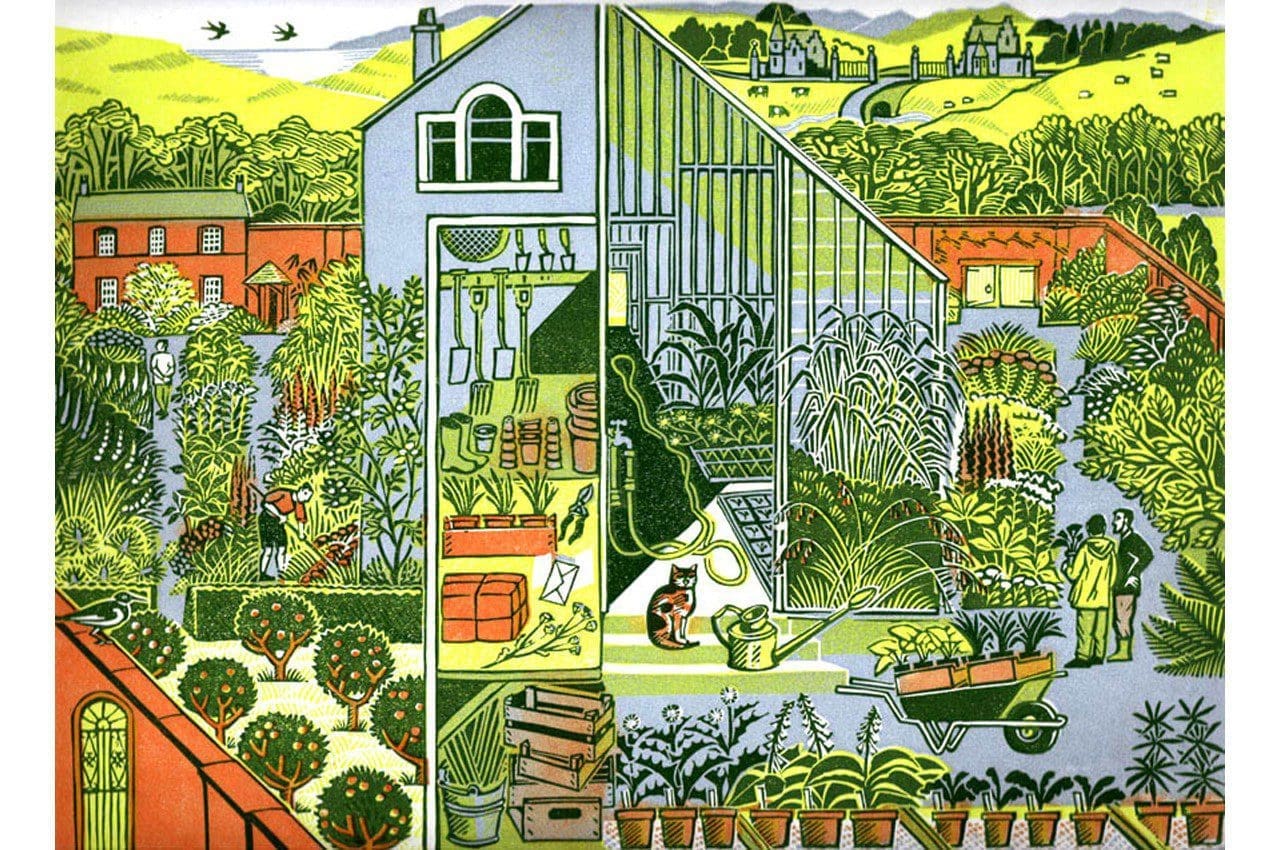

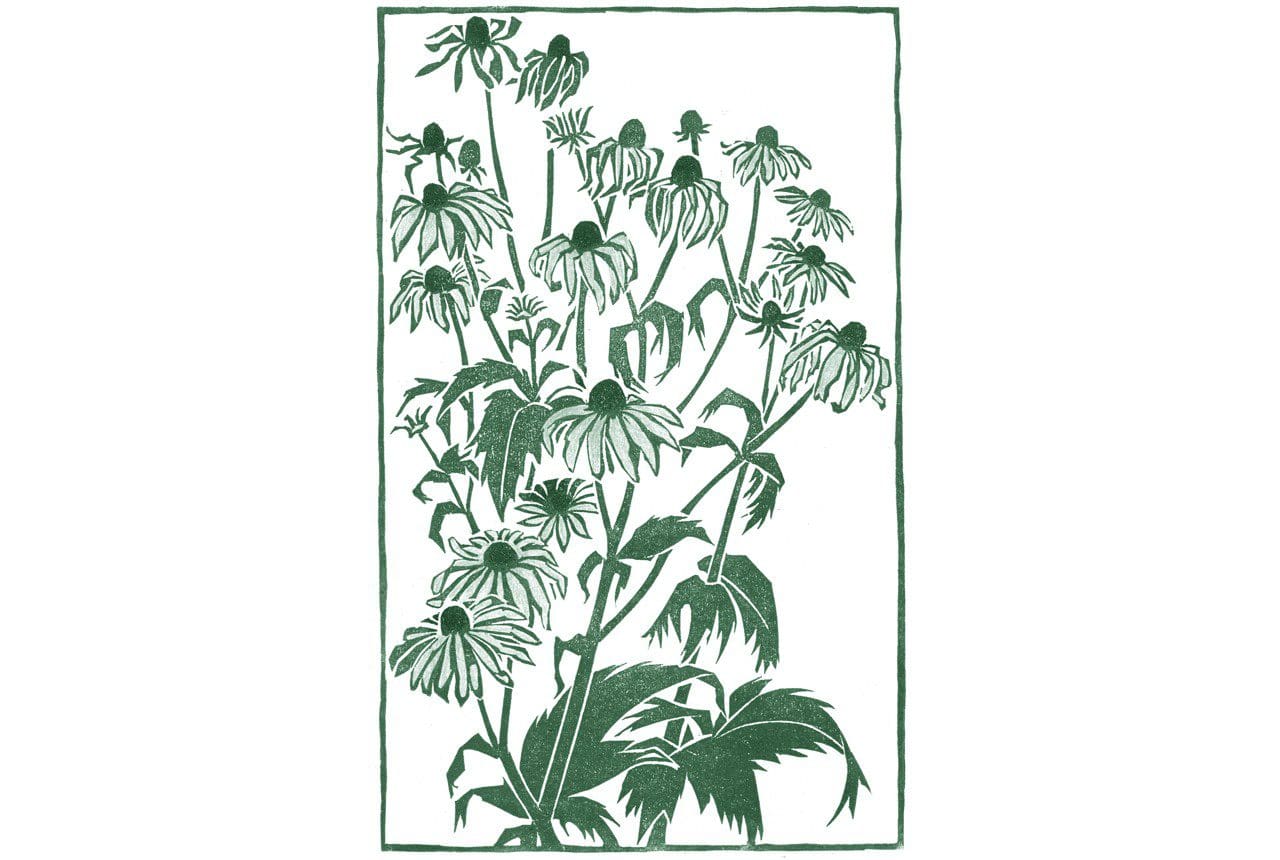

Clare Melinsky is a linocut illustrator, who created the cover and monthly chapter plant illustrations for Natural Selection, Dan’s new book which is being published by Guardian Faber on May 4. Clare was chosen for her keen eye for botanical detail, her innate understanding of plants and her talent for graphic simplicity.

You originally studied Theatre Design at Central School of Art. How did the change to linocut and illustration come about ?

In Theatre we had a seriously practical course with actual budgets for putting on productions with real actors. We stayed up all night sewing on buttons and painting scenery. It taught me about deadlines and responsibility, skills you would not normally associate with an art school education. And I also learned that the theatre world didn’t suit my temperament.

In the Foundation year at Central I had enjoyed a week of printing linocuts, and after I left college I did some linocut printing on textiles. A publisher friend, Richard Garnett at Macmillan, asked if he could use one of my motifs on a book cover: so I discovered the world of editorial illustration. At the same time Mark Reddy, a contemporary at Central, was starting out in advertising, and he, too, commissioned a linocut image from me. So I also discovered the existence of illustration in the commercial world. Both were much more financially rewarding than printing bedspreads and cushion covers. Light bulb moment: I would be an illustrator.

Illustration for Tesco wine label

Illustration for Tesco wine label

There is clearly a connection between theatre and the narrative complexity and framing of many of your illustrations. How do you go about identifying the elements required for a commission and then putting them together in a coherent whole ?

I have always enjoyed the research part of a job. As a student I spent many happy days ordering up stacks of dusty books from the card index at the V & A library, and sketching in the galleries. Now I have my own collection of reference books which I know inside out.

I like to get authentic detail of the time and place, and look for telling motifs rather than invent my own. For example the figure of Juliet on the Penguin Shakespeare cover is based on a tiny detail in an Italian fresco that I came across when looking at contemporary images, a lady leaning on a balcony: there was my Juliet. Having identified the elements, I then apply structure and colour and contrast to the specified size and shape in the short time available. Rather like garden design, I suppose.

The Holm

The Holm

You have said that your work is inspired by historic woodcuts. I can see echoes of Edward Bawden, Eric Ravilious and others in your work, and many of your plant portraits have a distinctly Japanese feel to them. Can you tell me about artists that have inspired you ?

I am a big fan of Bawden and Ravilious. I first came across their work at an exhibition at the Tate in 1977: The Curwen Press collection. It was a seminal moment. Before that I had studied technique by looking at Bewick’s wood engravings (1800-ish) and Joseph Crawhall’s popular woodcuts from the 1890’s.

Some years later I was given a secondhand book of mid 20th century Japanese prints collected by an American, Oliver Statler, when he was stationed in Japan after the war. These prints are known as Hanga: a revelation to me. A whole new way of looking at relief prints. More recently my daughter Jessie spent two years in Japan on a Daiwa scholarship doing part two of her architecture degree. So I was able to visit her in Tokyo, and travel during the traditional cherry blossom festival time which added a lot to my appreciation of Japanese style, and prints in particular.

Seeing the gardens in Kyoto was so exciting, in the context of their temples. Our accommodation in Kyoto was in a monastery, and we were expected to meditate in the temple for an hour before breakfast, which was mushroom broth. In the hillside moss garden, we saw the monks (or were they gardeners?) picking fallen leaves out of the moss to keep it pristine.

Euphorbia characias and Nerine bowdenii from the Cally Gardens Florilegium

Euphorbia characias and Nerine bowdenii from the Cally Gardens Florilegium

You have said that your garden can easily distract you from your linocuts. Can you tell me about your garden and what it means to you personally and professionally ?

After graduating I still lived in London. But my partner and I spent the summers with his sister’s young family in south west Scotland on their smallholding: we decided that was the life for us too. We started with twelve boggy acres at 1000 feet (300 metres). That means high up in the hills. We were the last house, six miles up a single track road in Dumfries and Galloway, south west Scotland. Sheep, goats, a dairy cow and calves, hens, two children, geese, a pony… we were very ignorant but it was a good life and I have no regrets.

It was originally my partner who was the gardener: we had a huge and productive veg plot, organic of course, with a big input of muck from the beasts. Very good soft fruit too. It was such a good lifestyle choice, because it meant that we could afford to live off my earnings in the early years. I could never have earned enough as an illustrator to support a family, if I had stayed in London.

After thirteen years it was time to move somewhere more sensible. Not far from our first house, but a bit nearer sea level and civilisation, we now have just one cat and a garden, with a wood at the back of the house and a burn running alongside. Lots of hardy perennial flowers and a small fruit and veg plot. Whenever the sun is warm I drop what I am doing and go outside with my gardening gloves on for a couple of hours. The climate here is so wet that you absolutely have to enjoy any fine weather when it comes.

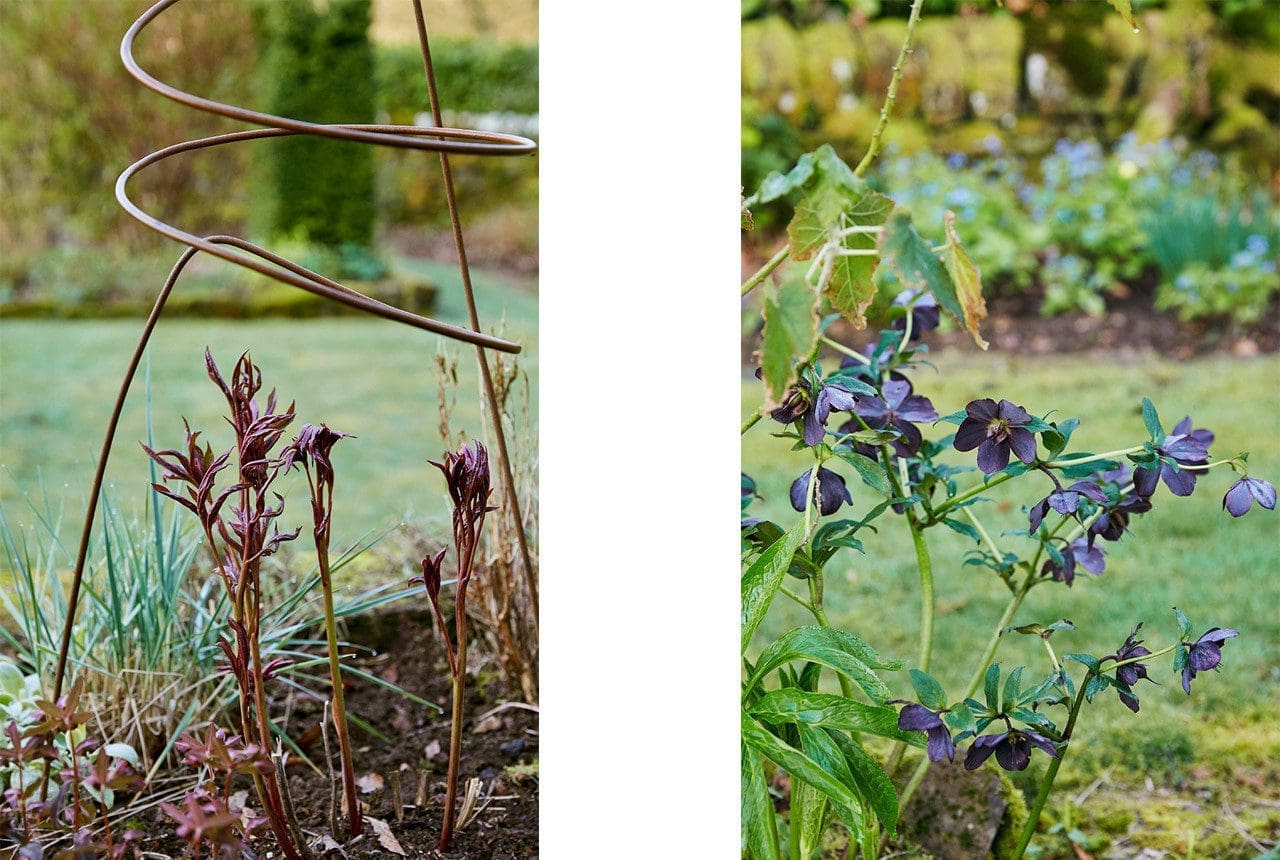

Clare’s house and garden in early April

Clare’s house and garden in early April

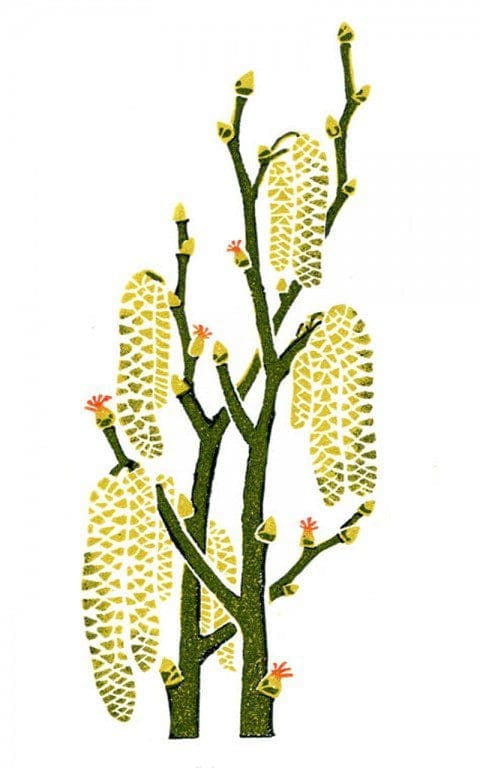

Hazel catkins

Hazel catkins

In the woods behind Clare’s house

In the woods behind Clare’s house

You work across a wide range of different media including book covers, stamps, product packaging and editorial. However, it seems that you include plants and landscape in your illustrations whenever relevant and possible. Can you tell me how your garden, landscape and plants inspire your work and influence the commissions that you accept ?

It’s what I see when I look out of the window. Most of my holidays are actually in cities by way of contrast: visiting my son Tom who lives and works in New York for example. I accept most commissions that come from my agent if I have the time: each job stimulates new ideas and creative development.

Gardening wasn’t a memorable part of childhood. I do remember individual plant experiences: a sea of lupins, as tall as us children, blue and pink and mauve, at the foot of the sand dunes on the Norfolk coast where we spent our summer holidays. A ravishing philadelphus enveloping the shed when I wheeled out my bike to cycle to school. A cataract of wisteria on an old rectory we used to visit.

My favourite toy at one time was a Britain’s Miniature Garden: little brown plastic rectangles and semicircles were the flowerbeds, dotted with holes into which you could push different clumps of coloured plastic flowers. You could buy individual flat-pack trees ready to assemble. Cardboard flagstone paths and rectangles of green flocked card with mowing-striped pattern. Little plastic rockeries and a pond and stone walls. I would save up my meagre pocket money to buy a new pack of plastic hollyhocks. Maybe that’s why I now have no hesitation in digging up a whole clump of perennials in full flower and replanting, if I decide that something is in the wrong place.

Whenever possible Clare draws from life using the plants in her garden

Whenever possible Clare draws from life using the plants in her garden

Tulips

Tulips

Given the breadth of your commissions do you have a favourite subject matter ? Which appeals to you most ?

My agent comes up with very varied jobs – and I like that. I was so lucky to be invited to join the Central Illustration Agency when Brian Grimwood first started it. It is the one thing that makes it possible for me to live in the country, and still access the world of work in London. There is no continuity to the work, it is completely unpredictable what people ask for. The client has chosen me because they like my linocut style. So it is often more of the same. Since I finished your book I have done images for food packaging for Waitrose, a folk tale illustration for Britain magazine, and some labels for a local cider maker. Sometimes it all goes quiet and I don’t get a job for six months.

Primula auricula

Primula auricula

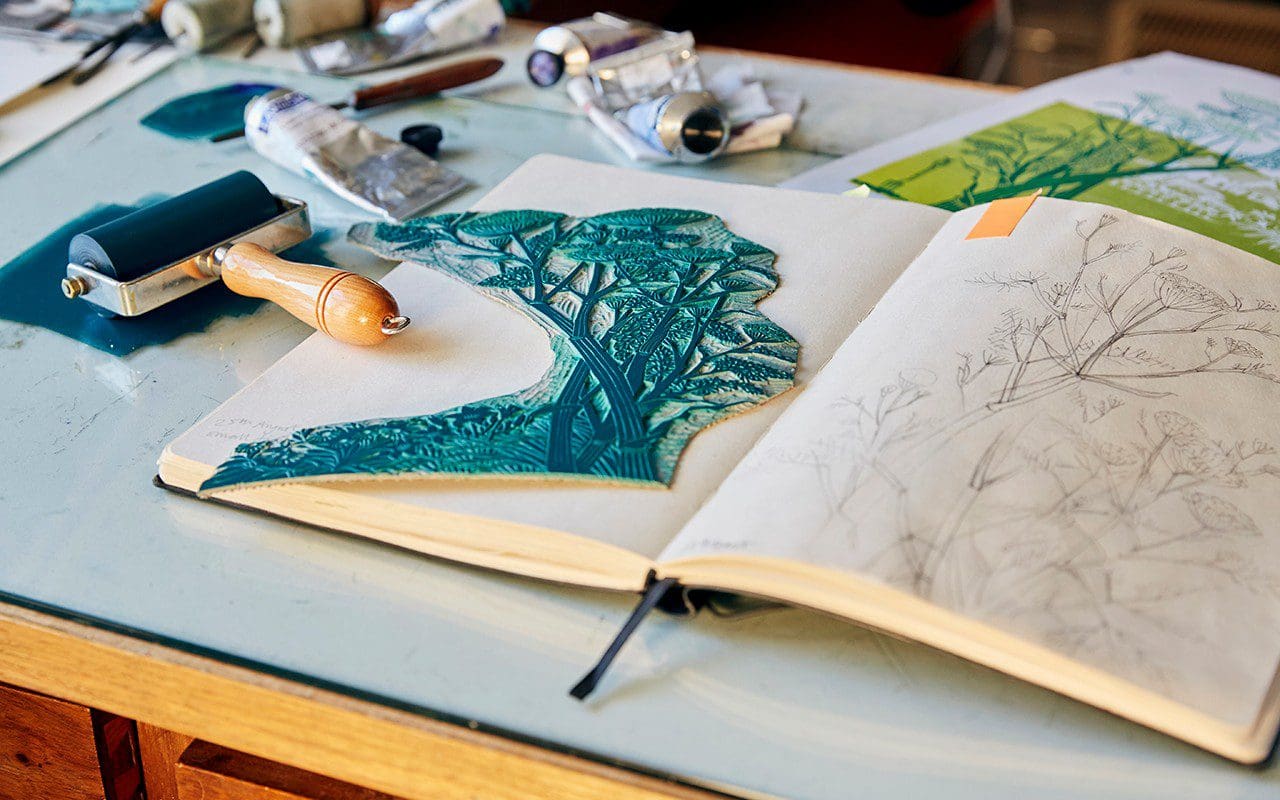

Can you explain your design process from sketch to finished print ?

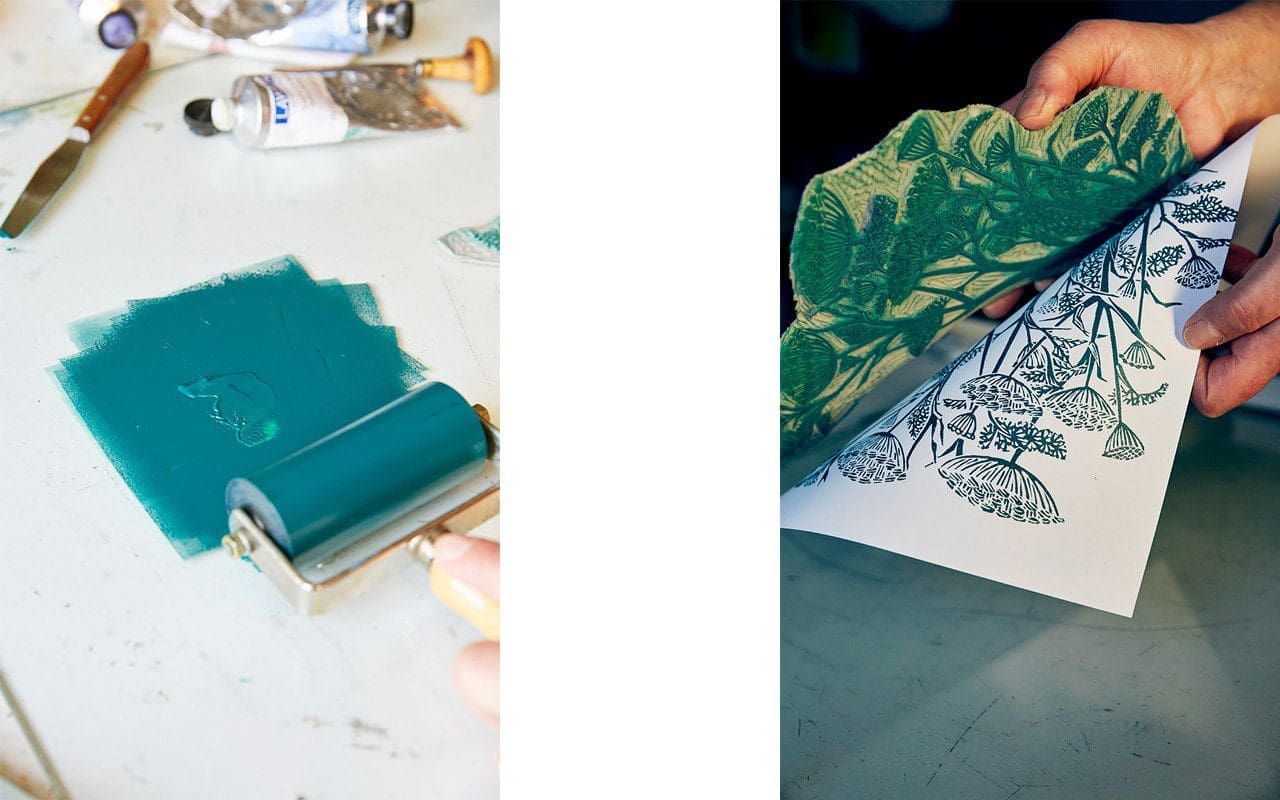

I do a rough drawing to show the client. Once that is approved, I transfer the image onto a piece of linoleum. I buy my lino from a flooring supplier by the metre. Cutting a design into a piece of lino calls for simplification and clarity. I am obliged to be selective. If in doubt, leave it out.

As it is a print, everything has to be done as a mirror image. I cut into the lino with a set of five small v-shaped and u-shaped gauges. I have to decide whether to show the veins on a leaf, or the outline of a leaf, or I can just depict the solid shape of the leaf. Less is more. The areas of lino that I cut away won’t print. When I roll the ink onto the finished block, the remaining lino will pick up the ink. Then I make a print using my big press.

I can print in black and white, but mostly my work is brightly coloured as it will be used on a book jacket or for packaging. I can add more than one colour onto each block using small rollers. Where the colours merge makes an interesting blend. Then when I print a second block over the first print, more subtle and interesting and unexpected things happen. The inks can be mixed to be quite transparent, or quite opaque. I use linseed oil-based relief printing inks from Lawrence. I was introduced to Lawrence’s at art school, when they were at Bleeding Heart Yard in London. I am still using the same tools that I bought there, though the smallest v-tool has been retired and replaced: it became rather short after years of sharpening.

Making the drawn line into a cut line transforms the quality of the line itself. I am still always surprised by what I have created when I see the first print.

How did you approach the commissions for Natural Selection ? The cover image features a house which looks very like Dan’s house in Somerset. Did you research images of it, or is it a happy accident that it looks so similar ?

I was so pleased to get this commission, I knew right away that I would love to do the book. If the house on the cover looks like Dan’s, then that is a happy accident: that’s my house more or less. Mine actually has dormer windows, but I thought Dan’s house would look more English with ordinary smallish windows.

I first came across Dan’s name in the early editions of Gardens Illustrated when it was something new and special. And have followed his career haphazardly, since I don’t have a television, in occasional gardening magazines. Dan decided to have one plant portrait for each month. We had different ideas about which plant, but I was happy to go along with his choices. The only problem was that by then it was October, so I couldn’t draw all the plants from life which would have been preferable. But mostly I had drawings that I could refer to. I happily use photos for reference, but I still think the best work is done from life if possible.

The hand-printed cover artwork for Natural Selection

The hand-printed cover artwork for Natural SelectionWhat are the greatest challenges in your work ? Can you tell me about the brief for the murals at Beatson Hospital in Glasgow ? How did you visualise your work for such a large piece and how did you scale up your linocuts for the site ?

I knew my linocuts would look good reproduced at a larger size. It enhances the irregular quality of the line, the handmade look. It was exciting to see the A4 size images enlarged to two metres high, extending over four thirty metre corridors. Each corridor was named after a Scottish island as a theme, and I rearranged my selection of details of the countryside to create a harmonious and varied flow of landscape and wildlife for patients and staff to enjoy as they passed by time after time.

The Beatson is the hospital for treating cancer patients in Glasgow, and the Macmillan Fund provided money for an art consultant, Jane Kelly, to enhance the whole interior with colour and style and fittings, with the Scottish west coast as the overall theme. Very worthwhile and successful.

Each job is a challenge. The deadlines are tight. Understanding what the client has in their head is a challenge: they often know what they want, it is my job to find out what that is and turn a concept into an artwork.

Part of the Beatson Hospital Mural

Part of the Beatson Hospital Mural

You have produced a number of illustrations for Cally Gardens over the years. It was a shock to hear of Michael Wickenden’s recent death in Myanmar while on a plant hunting expedition. Can you tell us about your relationship with Michael and the nursery ?

Michael’s fantastic nursery is an hour’s drive along the coast from here. He had bought a derelict walled garden thirty years ago and filled it with his vast collection of plants over the years. I was there doing a drawing for the Garden History Society. On seeing the final product, Michael asked if I would do a design for him to use on his Cally Gardens mail order brochure. We became firm friends, and the brochure has been published every year with my cover design. Until this year.

It is so sad that he is no longer with us, but I firmly believe he would be delighted to have died on top of a remote mountain on a great adventure. He knew that he was taking a big risk going to these remote places, and loved the expeditions, traveling with native guides under extreme conditions. As I tidy up my flowerbeds after the winter, I can recognise each plant that came from Cally, and I am reminded of Michael each time.

He was very outspoken and didn’t mind causing offence, objecting at every opportunity to the Plant Breeders Rights nonsense. I also learned from his example that my flowerbeds should be rigorously tidy in March. His garden looked like a jungle by the end of the summer, but in March everything (well no, maybe not everything, it’s a huge area) was cut back and isolated into its own distinct space. We all hope that some gardener with vision will grasp the nettle and keep the place going.

Illustration for the cover of the Cally Gardens catalogue

Illustration for the cover of the Cally Gardens catalogue

What are you working on at the moment ? What would be a dream commission ?

Just now I am designing a publicity image for an exhibition for the Royal College of General Practitioners. Then I have to print up more work for my local Open Studios event 27th-29th May 2017. I also teach linocut workshops, including residential courses at Higham Hall in the Lake District three times a year which I enjoy.

A dream commission: Natural Selection in an Italian palazzo with a cook and a housekeeper and a gardener. In the sun, with a swimming pool. With a whole year to do the work, so I could draw each plant from life. My partner and children and friends, and my agent, would come to visit at intervals… Interview: Huw Morgan / Photography: Emli Bendixen / All illustrations © Clare Melinsky

Interview: Huw Morgan / Photography: Emli Bendixen / All illustrations © Clare Melinsky

Eighteen months ago Guardian Faber approached me to compile a collection of articles from the ten years I wrote for The Observer. Natural Selection, with illustrations by Clare Melinsky, is due to be published this coming May and we prelude it here with a small selection to whet the appetite.

It was a privilege to be given the opportunity to write a weekly column and to record my gardening activities and ruminations in words over so many years. The pleasure I take in writing stems partly from this ability to record my gardening life and thoughts. The pieces span the whole decade and the shift – about half way through my time there – that charts the change from gardening in Peckham to the move we made to our land here in Somerset.

That move was the biggest change I have ever made in my gardening life and one that it has been good to look over again while editing the selection. The articles follow the course of a year, and explore the gradual seasonal changes that you are aware of through the act of gardening. Subject matters are invariably rooted in their moment, but they vary from the very practical and horticultural, to more in-depth essays about things I have fallen for or that have moved me and that I want to share with readers.

Writing is something that I enjoy for the act of pinning down a thought that may be fugitive or transitory. Gardening is when the best of these thoughts happen, and so one, it seems to me, would now be almost impossible to do without the other.

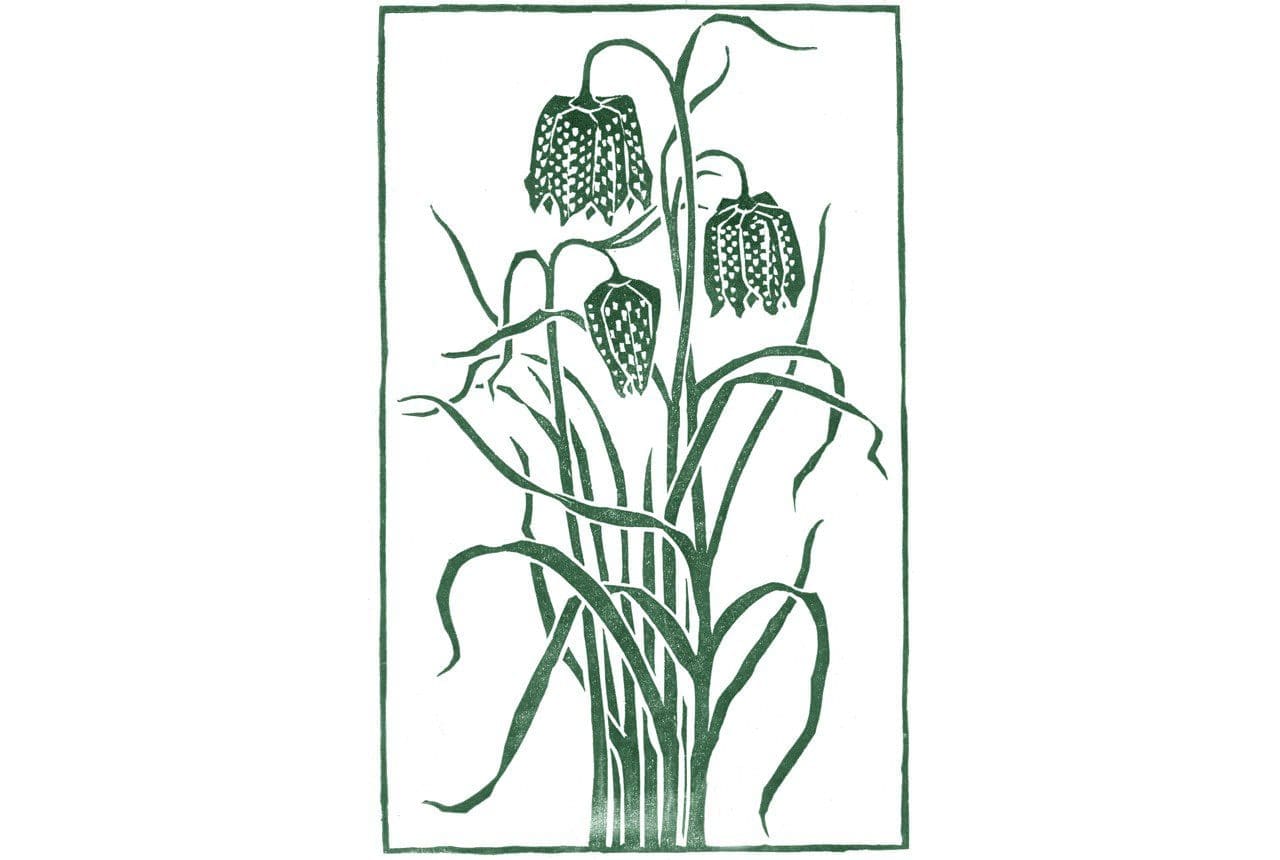

Fritillaria meleagris

SNAKES IN THE GRASS

5 April, London

One of my clients lives in a sturdy stone cottage in the Yorkshire Dales. It sits on the brow of a hill, facing south, with the valley sweeping away as far as you can see to either side. There are dry-stone walls sectioning the land and on the far hills the haze of heather smudges the tops in August. You feel the weather with intensity. When I was last there the January gales made the house shudder and the valley was a pure and glistening white with frost. But now, at the beginning of spring, the most extraordinary thing happens. The midwinter green increases in intensity over a week or so until it could only be described as luminous. It is like nature turning up the contrast so that the fields appear to be pulsing green. Go down into the valley and the hedges will be thrumming with activity. Bristling new shoots on the hawthorn, Stellaria smattering the base of the hedgerows and young nettles as soft as they ever will be, at the best moment for making into soup. Cowslips will be gathering in strength in the open ground where the turf is kept short and when the tops of the first new grass are bent over on a bright breezy day, the meadows will literally shimmer with reflected light. This is all good news after a long grey winter and I plan to make the most of this glorious moment. It involves studding the shiny new meadows with sheets of bulbs, not great sweeps of colour-heavy daffodils, but with species bulbs that will scatter colour.

No meadow in early April would really be complete without the Fritillaria meleagris and in a week these snakeshead fritillaries will be at their best. Pushing up on wire-thin stalks, they are almost impossible to see until they arch their heads over in readiness to flower. And flower they do in abundance when they decide they are going to naturalise a sward. The sight of them in countless numbers is breathtaking. They like to naturalise low-lying floodplains and there are some incredible colonies in the lowlands of Cambridgeshire, Oxfordshire and Wiltshire. They used to be more common, but with ground drained for agriculture and building spreading as it is, the wild colonies are now few and far between.

Last year I visited a good example just inside the ring road that runs around Oxford. It was odd to be among them, sitting in spring sunshine with the Juncus and ragged robin indicating how wet the land lay year round and the traffic hurtling by. Their chequered pattern never fails to delight me. It really is like the patterning on a snake. Mulberry overlaying pale silvery scales in the dusky forms and green overlaying white in the rare but ever-present albinos. The flower looks like it has been made from fabric and starched into position with its high-pleated ‘shoulders’.

I have no grass at home in London so I have chosen to keep a couple of dozen bulbs in a pot so that spring doesn’t go by without me enjoying them. I am amazed that they do as well as they do because they are a plant that looks so much better in the wild and only really does well where the ground is damp. I do nothing more with them than bring them out from the holding area in the shade when they show and then allow them to feed up their foliage until it withers in early summer sunshine after they have flowered. The pots are filled with Viola labradorica so that they are not too bare for the rest of the year and they are completely neglected beyond the watering that is needed to keep the Viola alive and kicking.

Establishing Fritillaria meleagris in a garden setting is fairly straightforward as long as you remember their requirement for damp ground. This is unusual in a bulb, for most like to be on the dry side when they are dormant. Soil that floods infrequently and in winter will be fine, but really they like to draw upon water rather than lie in it for long periods so it is worth bearing that in mind. Though I have had success planting the bulbs in the autumn at two-and-a-half times their own depth, as most bulbs like to be, I have heard that they prefer to be planted deep, up to 15 cm. If you can get plants pot grown, though not the cheapest way to introduce them in numbers, it is the surest way of getting them established. As with any other bulbs grown in grass, leave them for five to six weeks after the flowers fade to seed and store goodness for the following year.

The fritillarias are a huge tribe of wonderful treasures and most hail from Turkey and the Middle East where they bake bone dry not long after the spring rains are finished. It is hard to see many of these in the wild now because grazing has stripped the colonies as has unscrupulous bulb collection, but try and see them in the alpine houses of botanic and RHS gardens. You will be bewitched. Most of these species are beyond me at this point in my gardening history. They need to be grown in frames and given just-so attention, but there are several which are less choosy. The earth-brown and green F. acmopetala and F. pyrenaica are easy. My childhood neighbour Geraldine had a wonderful clump of the latter growing for years in free draining ground through some low perennial campanulas. Then there is the exquisite F. thunbergii from China, with its grass-like foliage, twisted at the tips to haul itself up into the low scrub in which it likes to grow. This is a woodlander that the garden designer Beth Chatto grows well against the odds in Essex. Its exquisite green bells are the perfect companions to Trillium and Uvularia in her sheltered woodland garden.

In areas of the country where the dreaded lily beetle has yet to make its presence felt or where you can be prepared to pick off the first generation of beetles and grubs, I will always make room for F. persica. Tall, at about 90 cm, in the strongest selection ‘Adiyaman’, the whirl of blue-green foliage is up early in March and the grape-purple flowers follow fast behind. This is a plant that loves to bake, so think about it being with thymes and small lavenders, Origanum and the like. It will be withered and below ground by mid-summer having lived fast and furious.

The Crown Imperials are closely related but a scale up again in impact. Perhaps they were brought here along with the tulips as part of the trading that used the ancient silk routes. Hailing from Turkey through to Kashmir they must have been exotic treasure, and their provenance explains why you often see them depicted in medieval woodcuts of apothecary gardens and in the floral paintings of the old Dutch masters. The flowers, which hang from a cluster at the top of a waist-high shoot, were said to have not hung their heads when Christ passed them on his way to the crucifixion. They are forever bound to bow their heads as a result. Lift them up and in the base there will be a tear of nectar at the heel of each petal.

The bulbs, which go in as usual in the autumn, have a pungent foxy odour and there is something of that in the glossy leaf. They are happy in a hot spot and in good hearty, free- draining soil. ‘Lutea’ is a bright chrome-yellow, ‘The Premier’ a dusky orange and there are brick reds that never look better than when basking in spring sunshine. They display none of the earthy tones of their many relatives, nor the snaky subtlety of our British native, but every bit as much individuality.

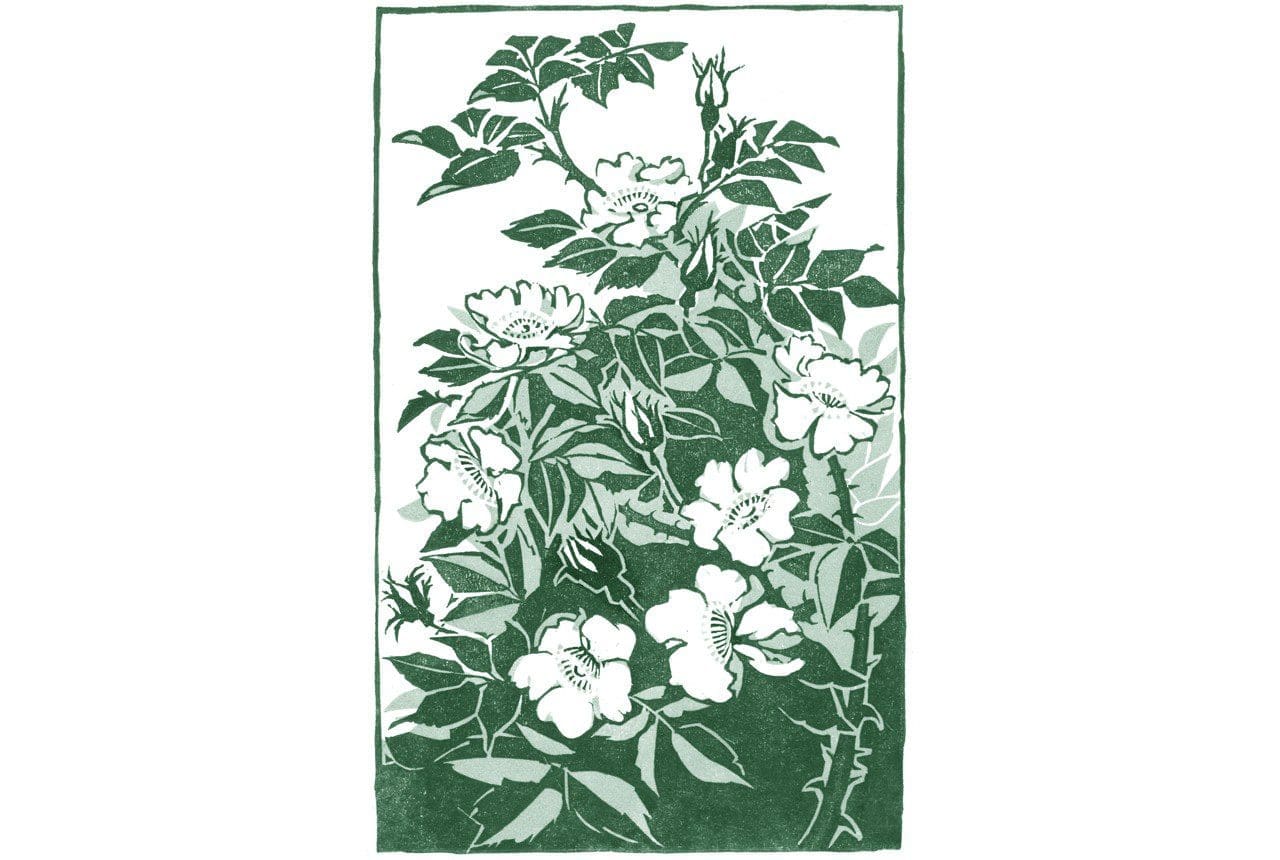

Rosa laevigata ‘Cooperi’

Rosa laevigata ‘Cooperi’

PLEASURE GARDEN

8 June, London

After finishing my studies at Kew in 1986, I spent about five years moving around: a year at Jerusalem Botanic Garden, a year a mile up a dirt track on Miriam Rothschild’s wild and woolly estate at Ashton Wold, and time out on the Norfolk Fens. I had plans with my partner at the time to buy a field on the Milford Haven estuary, where we intended to live on our houseboat and make a garden, but when my garden design business started to take off, I found myself inching back to London. I was twenty-seven and in love again, which is how I came to live on Bonnington Square, in south London.

The first time I saw the square I knew I wanted to live there. There was a party house with no floors, children running barefoot in the street, a cast of local characters who were the definition of bohemian, and the Bonnington Square Cafe, which is still run on a vegetarian co-operative basis. Friends dropped in with no notice and frequently stayed until dawn, and the boundaries between where you lived and where you spent your time were constantly blurred. One summer morning I awoke to find the outside of the house opposite had been papered from top to bottom in newspaper. Visitors often said it was like stepping back in time.

Although the Harleyford Road Community Garden on the other side of the square existed when I arrived, the greening of the square had now started. Cracks in the pavements had been dug out and planted up by the local guerrilla gardeners, and odd corners were already colonised. I had just been for the first time to New York, where I was inspired by the Operation Green Thumb community gardens on the Lower East Side. The same sense of a community working to improve its surroundings set the square apart from the roaring traffic of Vauxhall Cross, and that community has gone on to develop as one of my favourite gardens in central London.

My roof garden overlooked the site where this garden was created, on an area seven houses long that was bombed during the war. A chain-link fence surrounded the site, which had been turned into a children’s playground in the seventies, with a broken slide and dilapidated swing sitting on a pad of dog-soiled concrete. Although someone had planted a lone walnut tree, bindweed and buddleia had won the day.

In 1990 a builder asked the council for permission to store equipment on the waste ground, which alerted locals to the potential for development interest in this area of open land. Fast as lightning, Evan English, one of my neighbours, proposed that the site should be turned into a community garden. With a core group of residents behind him, he struck lucky with a local councillor who had one of the last GLC grants to give out to such a project. So, with just over £20,000 in our pockets and a team of council-appointed landscape architects, we put in the bones of the new garden.

The chain-link fence was replaced with railings, the tarmac and concrete with hoggin, and a series of raised beds created with topsoil spread over the basements of the old houses. A giant slip wheel, salvaged from the defunct local marble works, was partially reassembled to add a dramatic sculptural element. Another resident, the New Zealand garden designer James Fraser, and I put together the planting scheme and had a lot of fun mixing architectural New Zealand natives and English garden staples. A massive planting day that first autumn was followed by another party. None of this could have happened without Evan’s single-mindedness, and once the momentum was up, so was the support of the community. There was an annual street fair to raise additional funds for plants and furniture, and monthly workdays to keep the garden looking its best.

The square was given an entirely new focus with a garden at its core and created a renewed sense of pride among the residents. It was then given its official name, the Bonnington Square Pleasure Garden, partly a reference to the notorious seventeenth-century Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens, partly because it had been a pleasure to create and was intended to be a pleasure to use. Life on the square had changed. The picnic lawn was busy every weekend, and we saw people who had never ventured from their houses using the park as an extension of their homes.

The following year came the Paradise Project, a plan to green the streets around the square. We were given more help with funds for trees, and soon catalpas, Judas trees, mimosa and arbutus took to the pavements – and climbers to the walls of anyone who wanted to green their building. People quickly started to plant up the pavements in front of their houses. Window boxes of herbs and flowers appeared, old telegraph poles were colonised by morning glory and vines, and a rash of roof gardens appeared, so I was no longer alone in my green eyrie.