The woods in the hollow below us have finally been stripped of foliage to reveal bare bones and the silver-grey of the lichens that outline their trunks and branches. The garden has also dimmed, the last of the asters finally over and the summer foliage withered. In this new incarnation we are left with something altogether different. A garden still standing, but bleached of colour as it moves into the first throes of winter.

Every week there are changes as the falling away reveals the skeletons that have the stamina to stand against the winter. The new transparency allows us to see to the ground now where the evergreen rosettes are already hunkered and providing new interest. Remarkable for the fact that they have been there in the shadows all this time and slowly building in strength are the Lunaria annua ‘Chedglow’. It was a delight to discover that the first generation of self-sown seedling have found their niche, nestled under the Salix purpurea ‘Nancy Saunders’ amongst the pulmonaria.

Lunaria annua ‘Chedglow’

Lunaria annua ‘Chedglow’

This dark-leaved honesty is a refined selection and more ornamental than most with its burnished, Ace of Hearts foliage. It is hard to describe the colour, which on close observation shimmers deepest purple over a base of bitter chocolate. Just discernible at the centre is a shading to dark forest green. I have not yet built up a mix of generations in this young colony because my original plants flowered and seeded last year, but in time we will have enough plants for the satiny coins of seedheads to shine against this inky background. For now though the rosettes will provide a good foil for a group of February-blooming yellow hellebores that are clumping nicely and the lunaria flower, when it comes in April, will be a strong contrast to the primrose of the Molly-the-witch peonies which are also part of this grouping. ‘Chedglow’ has a good dark flower which is a dusky mauve, not the bright purple of the more commonplace honesty.

Lunaria annua ‘Corfu Blue’

Lunaria annua ‘Corfu Blue’

Up by the barns and far away so that ‘Chedglow’ does not cross-pollinate and lose its lustre, I have Lunaria annua ‘Corfu Blue’. Though most are biennial, this particular form of honesty is said to be perennial. I am not sure that it really is, with only the odd plant coming again for a second year of flower, but the best ones are always those that seeded the year before and have built up a decent rosette in readiness. My original plants, which came from Derry Watkins at Special Plants, have now seeded freely in the gravel. The flattened seedpods of lunaria are a magical thing as they develop, first green and then becoming pale and luminous like their namesake as they mature. The dark seed, also flattened, is suspended between three sheaths of papery tissue which silvers before buckling to drop its cargo in late summer. The remains of the honesty will be around for a while yet, capturing wintry light.

Baptisia ‘Dutch Chocolate’

Baptisia ‘Dutch Chocolate’

At the other end of the spectrum are the seedheads of baptisia, matt charcoal black when you see them suspended in a garden that is drained of chlorophyll. I have five or six different selections in the garden now, which are proving their worth both with their lupin-like flowers and good summer structure. In autumn each has its own habit, some colouring buttery yellow before the leaves fall, whilst others darken, the leaves metallic grey, like pewter and hanging on for quite some time before dropping. Here we have ‘Dutch Chocolate’, but ‘Caramel’ and ‘Starlite Prairieblues’ also produce a good seedheads.

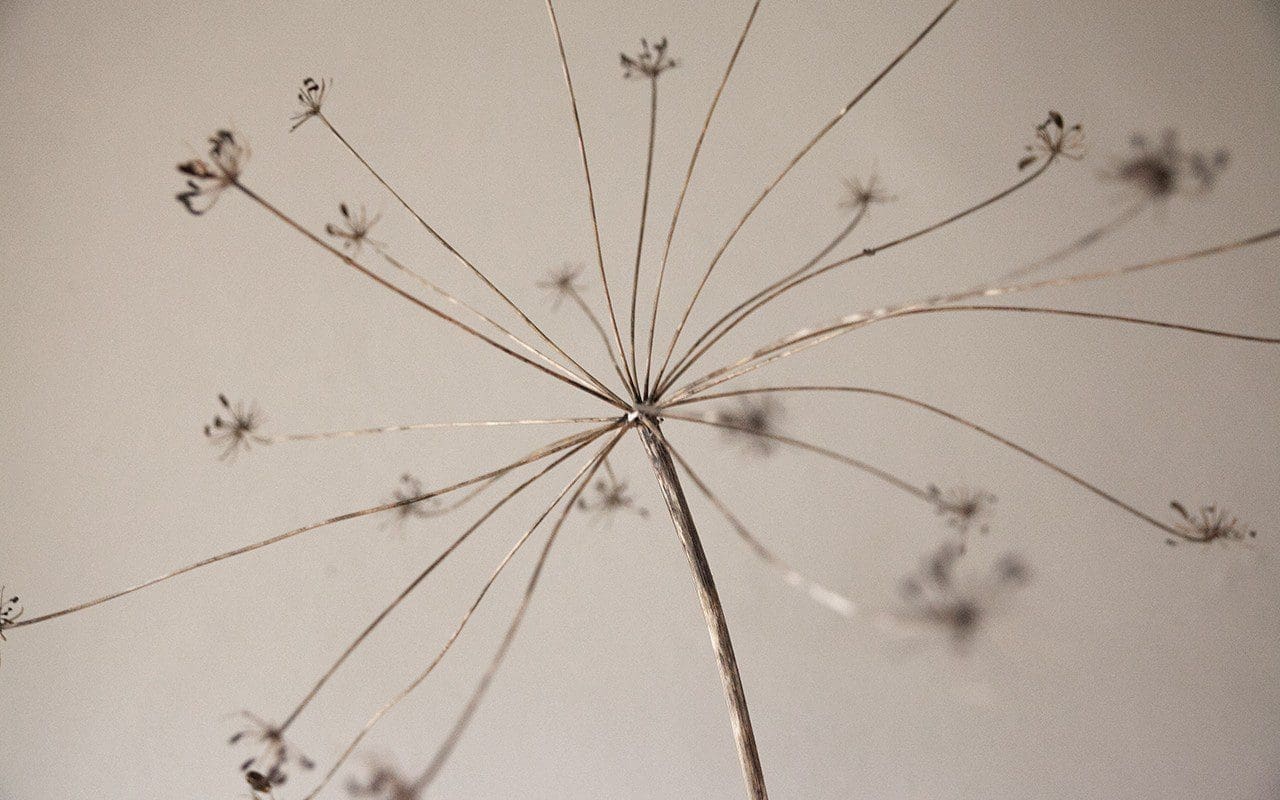

Laser trilobum

Laser trilobum

And finally, to give a feeling of the fragile remains in the garden this first week in December, are the spidery seedheads of Laser trilobum. This light-footed umbellifer moves away quickly from a glaucous leafy rosette in early summer to stand just over a metre high on wiry stems. The umbels can reach as much as 30cm across, so I give it plenty of room to hang loftily above low-growing Geranium macrorrhizum and white Viola cornuta. As an edge of woodlander it feels right amongst this cool greenery. Although it is reliably perennial, most of the seed has already dropped. It germinates easily in the right spot and, all being well, it will find its way into the planting on its own, to add the same dramatic delicacy of scale with its elegant, widely-spoked umbels, as it does here.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan Published 1 December 2018

Simon Jackson (above right) is a pharmacognosist and cosmetician who is passionate about creating personal products that are derived from scientifically proven, sustainably produced active plant extracts. After a long and wide-ranging career as a scientist, researcher and cosmetic product innovator, for the past two years he and his husband, John Murray (above left), have been developing a new range, Modern Botany, using British native plants grown near their home in the West of Ireland. Simon, you have taken an interesting and varied route to where you are now. Can you give us a brief explanation of where your interest in the therapeutic uses of plants started and your training ? Interesting? Varied? I think they call it a career portfolio nowadays! OK, how long do we have? As you can imagine I’ve got a lot to say on plants and their therapeutic uses. I guess it all started in Lincolnshire. I grew up in a small village and my love of plants came from my grandmother, Cath Jackson. She was a keen amateur gardener and she taught me all the Latin names of plants when I was very young. She had a small plot of land and was very proud of all her plants and I used to help her gardening. She had a beautiful allium that came up year after year, and it was quite unusual in the early ‘70’s to have such unusual plants. She introduced me to Sir Joseph Banks, a famous Lincolnshire botanist. There is a big monument to him in Lincoln Cathedral, and his home town of Horncastle was close by, so the seed was planted. Skip forward about 20 years, and I found myself studying at Manchester Metropolitan University in 1989. I did a course in Applied Biological Sciences and specialised in Drug Discovery and Toxicology. Back in the late ‘80’s it was called Plant Defence Mechanisms. When plants are put under pressure externally or attacked by herbivores, they excrete defence chemicals. Salicylic acid is one of them. It has a bitter taste so wards off any herbivores, but it also has medicinal properties for humans too. Aspirin we call it. It was here that I learnt about ethnobotany, and how traditional cultures use plants. For example, it was the native Americans who used willow bark during childbirth as an analgesic to help with pain relief. I just thought this was amazing and so, as part of my degree, I undertook an expedition to Indonesia. The year was 1992, and it was in the middle of all the atrocities in Timor, but I was quite gung-ho even back then, and just wanted to learn more about plants and their traditional uses. We lived on an island called Sumba. It was very primitive back then, no luxury hotels or surf dudes like there are now, but I took part in what was one of the first pharmacy conservation projects in an Indonesian primary rainforest. I was cataloguing species of plants around the island and understanding from the locals any economic uses they had, which could be medicinal, or as dyes or fuel or even as building materials. The aim was to set up some sustainable practices for harvesting these plants. It was on the island of Sumba that I remember being introduced to a village chief. I had wandered off into the rainforest one day a bit too far on my own away from base camp, and he found me walking in the wrong direction (I have a terrible sense of direction) and brought me back to camp on the back of his Sumbanese pony, an indigenous breed of horse on the island. Seeing the hornbills flying back at dusk and the Sumbanese green pigeons (they look like parrots) it was here that I learnt from him about the traditional uses of plants, and it was here that I had my cathartic moment and realised it was traditional plants I wanted to study. That’s why I had majored in Drug Discovery and Toxicology. I also worked in the Herbarium in Bogor, and met Professor Kostermans, an amazing ethno-botanist, who regaled me with all his stories of expeditions in Indonesia, Borneo and Sumatra. He was a POW during the war and only survived by learning from the locals how to utilise the native plants for food and medicine. And that was it. I was hooked. Simon (left) on a field trip to Indonesia in 1992

I decided that, to be taken seriously, I would need to further my education and get a Masters and PhD in Natural Product Science. I did a bit of digging and found one of the only centres to do such a thing was King’s College in London, where they had a Pharmacognosy Department in the School of Pharmacy. I enrolled in a 3 year PhD programme in 1993 under Professor Peter Houghton. It meant that I had to get top class honours in my first degree, but it was something I really wanted to do and so passed with flying colours.

It was a bit of a culture shock initially, going from ‘Madchester’ in the early ‘90’s to Chelsea in London, but it was under Professor Houghton that I really learnt my trade. Pharmacognosy has been around for a long time and we can record how humans have used plants back to the Stone Age, but Western medicine goes back as far as the Greek philosophers. Dioscorides (40-90AD) was one of the first to document the ‘De Materia Medica’ or medical material, and it’s from here that we find the origins of Western medicine. The ‘De Materia Medica’ was the first precursor to all modern pharmacopeias. Meaning ‘drug making’ in Greek these are books published by governments or medical bodies which contain the directions for the identification of all compound medicines.

So at King’s College, I learnt that pharmacognosy is a multidisciplinary study drawing on a broad spectrum of biological and socio-scientific subjects, but in short: botany, medical ethnobotany, medical anthropology, marine biology, microbiology, herbal medicine, chemistry, biotechnology, phytochemistry, pharmacology, pharmaceutics, clinical pharmacy and pharmacy practice.

The contemporary study of pharmacognosy is broken down into;

Medical ethnobotany: the study of the traditional use of plants for medicinal purposes

Ethnopharmacology: the study of pharmacological qualities of traditional medicinal substances

Phytotherapy: the medicinal use of plant extracts

Phytochemistry: the study of chemicals derived from plants, including the identification of new drug candidates derived from plant sources

Although most pharmacognostic studies focus on plants and medicines derived from plants, other types of organisms are also regarded as pharmacognostically interesting, in particular microbes, like bacteria, fungi etc – think antibiotics – and more recently marine organisms, for example some interesting anti-cancer products derived from sea sponges.

If anyone is interested I can talk about this for hours, but what I’m finding is that there are less and less places to study this arm of medicine. It’s usually linked with pharmacy departments, but what’s interesting is that more and more people are asking me where they can study this.

Anyway, there finishes my first lecture in pharmacognosy! I have several more weeks worth of lectures, but I’ll leave it there for now. I hope it gives you a good overview.

So, after King’s College, I then did a Post Doctorate at Kew Gardens in the Jodrell Laboratory. It was 1993 when I started at King’s, so it must have been around 1996. I remember living in digs in Chelsea – a lovely old farmhouse in Parsons Green – and Carol Klein was living there in the lead up to the week of the Chelsea Flower Show. So I ended up helping her out putting her stand together in the marquee (I was the manual labour), but that was when I first met you, Huw, and Dan. Carol introduced me to you both and I think Dan had just won his first ever Gold at Chelsea. Anyway, I digress.

You have travelled a lot to research the plants that you have been interested in, and spent periods of time living with indigenous tribes in Africa and South America. What were some of the most interesting things you discovered on your travels ?

Yes, I have been lucky to travel to many places around the world. As I said I started out in Indonesia, which really inspired me to study medicinal plants. I remember meeting the local ladies in the market and they were making Jamu, a natural health tonic, and selling all the raw ingredients. Every tribe or family had a different recipe. It was amazing to see everyone so healthy and living to ripe old ages with no NHS interventions, chewing betel nuts and spitting the bright red saliva all over the floor.

Next was South America. I was lucky enough to be invited as guest speaker at the first Pharmacy from the Rainforest Conference in the Amazon in the ACEER Camp in Peru. It took a few days by dugout canoe to get to the research station, but what an amazing experience. It was here that I met the famous American ethnobotanist, James Duke, and Mark Blumenthal and the rest of the American Botanic Council team. I now and again write articles for their Herbalgram magazine on medicinal plants.

In the rainforest of the Amazon (this is pre-Sting going there), I had no idea what to expect, but we witnessed the shamanic ayahuasca ceremony and learnt how to harvest the raw ingredients to make the hallucinogenic recipe. I met my first shaman, which was quite an experience, and learnt so much about South American plant species. One that sticks out is the Croton lechleri or Sangre de Drago. I still use it today if I get bitten or if I get a small cut. It’s great as a ‘second skin’ and really does reduce any inflammation from bites. Do check it out. You can buy it online and in good health food shops.

Simon (left) on a field trip to Indonesia in 1992

I decided that, to be taken seriously, I would need to further my education and get a Masters and PhD in Natural Product Science. I did a bit of digging and found one of the only centres to do such a thing was King’s College in London, where they had a Pharmacognosy Department in the School of Pharmacy. I enrolled in a 3 year PhD programme in 1993 under Professor Peter Houghton. It meant that I had to get top class honours in my first degree, but it was something I really wanted to do and so passed with flying colours.

It was a bit of a culture shock initially, going from ‘Madchester’ in the early ‘90’s to Chelsea in London, but it was under Professor Houghton that I really learnt my trade. Pharmacognosy has been around for a long time and we can record how humans have used plants back to the Stone Age, but Western medicine goes back as far as the Greek philosophers. Dioscorides (40-90AD) was one of the first to document the ‘De Materia Medica’ or medical material, and it’s from here that we find the origins of Western medicine. The ‘De Materia Medica’ was the first precursor to all modern pharmacopeias. Meaning ‘drug making’ in Greek these are books published by governments or medical bodies which contain the directions for the identification of all compound medicines.

So at King’s College, I learnt that pharmacognosy is a multidisciplinary study drawing on a broad spectrum of biological and socio-scientific subjects, but in short: botany, medical ethnobotany, medical anthropology, marine biology, microbiology, herbal medicine, chemistry, biotechnology, phytochemistry, pharmacology, pharmaceutics, clinical pharmacy and pharmacy practice.

The contemporary study of pharmacognosy is broken down into;

Medical ethnobotany: the study of the traditional use of plants for medicinal purposes

Ethnopharmacology: the study of pharmacological qualities of traditional medicinal substances

Phytotherapy: the medicinal use of plant extracts

Phytochemistry: the study of chemicals derived from plants, including the identification of new drug candidates derived from plant sources

Although most pharmacognostic studies focus on plants and medicines derived from plants, other types of organisms are also regarded as pharmacognostically interesting, in particular microbes, like bacteria, fungi etc – think antibiotics – and more recently marine organisms, for example some interesting anti-cancer products derived from sea sponges.

If anyone is interested I can talk about this for hours, but what I’m finding is that there are less and less places to study this arm of medicine. It’s usually linked with pharmacy departments, but what’s interesting is that more and more people are asking me where they can study this.

Anyway, there finishes my first lecture in pharmacognosy! I have several more weeks worth of lectures, but I’ll leave it there for now. I hope it gives you a good overview.

So, after King’s College, I then did a Post Doctorate at Kew Gardens in the Jodrell Laboratory. It was 1993 when I started at King’s, so it must have been around 1996. I remember living in digs in Chelsea – a lovely old farmhouse in Parsons Green – and Carol Klein was living there in the lead up to the week of the Chelsea Flower Show. So I ended up helping her out putting her stand together in the marquee (I was the manual labour), but that was when I first met you, Huw, and Dan. Carol introduced me to you both and I think Dan had just won his first ever Gold at Chelsea. Anyway, I digress.

You have travelled a lot to research the plants that you have been interested in, and spent periods of time living with indigenous tribes in Africa and South America. What were some of the most interesting things you discovered on your travels ?

Yes, I have been lucky to travel to many places around the world. As I said I started out in Indonesia, which really inspired me to study medicinal plants. I remember meeting the local ladies in the market and they were making Jamu, a natural health tonic, and selling all the raw ingredients. Every tribe or family had a different recipe. It was amazing to see everyone so healthy and living to ripe old ages with no NHS interventions, chewing betel nuts and spitting the bright red saliva all over the floor.

Next was South America. I was lucky enough to be invited as guest speaker at the first Pharmacy from the Rainforest Conference in the Amazon in the ACEER Camp in Peru. It took a few days by dugout canoe to get to the research station, but what an amazing experience. It was here that I met the famous American ethnobotanist, James Duke, and Mark Blumenthal and the rest of the American Botanic Council team. I now and again write articles for their Herbalgram magazine on medicinal plants.

In the rainforest of the Amazon (this is pre-Sting going there), I had no idea what to expect, but we witnessed the shamanic ayahuasca ceremony and learnt how to harvest the raw ingredients to make the hallucinogenic recipe. I met my first shaman, which was quite an experience, and learnt so much about South American plant species. One that sticks out is the Croton lechleri or Sangre de Drago. I still use it today if I get bitten or if I get a small cut. It’s great as a ‘second skin’ and really does reduce any inflammation from bites. Do check it out. You can buy it online and in good health food shops.

The ACEER Camp in Peru

The ACEER Camp in Peru

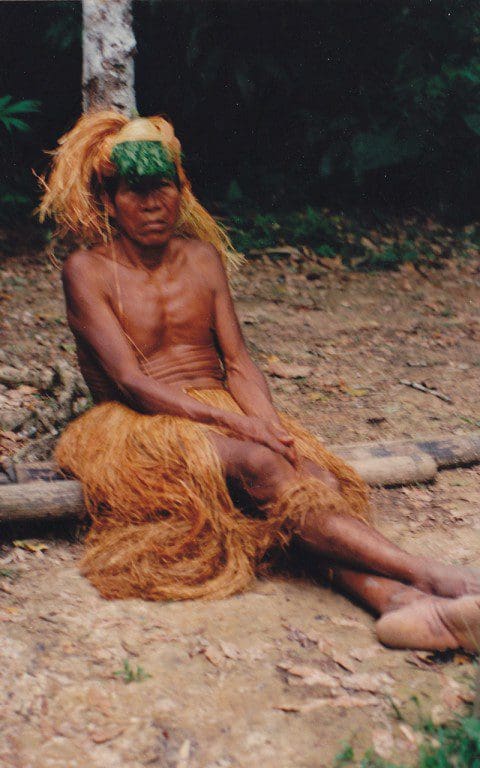

Jaguar shaman in the Amazonian rainforest

What can you tell us about your research into the uses of African medicinal plants as therapeutic agents in oncology ?

I did a lot of research as part of my PhD. My professor was one of the world experts on Kigelia pinnata, the sausage tree, which has been used traditionally against malignant melanoma and solar keratosis, and my PhD thesis was a study of compounds isolated from this plant against skin cancer. I worked at Charing Cross Hospital in London, isolating the active compounds and testing on human melanoma cell lines (tissue culture). We identified several compounds that showed activity, but it can take over 10 years and up to $100M to discover a new drug, so this work is still ongoing and will take many years to create any new medicines.

You yourself are now a world expert on Kigelia pinnata. What can you tell us about it ?

Crikey, that sounds grand, but I guess there are not many people who have researched Kigelia pinnata. I co-wrote a lovely paper for Herbalgram which gives you an outline of the plant. It’s quite an amazing species which belongs to the Bignoniaceae family, which also includes the catalpa tree from South America. It contains a compound called lapachol, which was taken forward for cancer research, but it was found to be quite toxic in vivo (animal)studies and so was dropped, but I still think it’s a plant family that needs a lot more research to be undertaken. I’m hoping one day I can pick up the baton again and take this research further.

My theory is that plants used for traditional medicine make greater leads for new drug discovery as they have been used for many thousands of years, so there must be a reason why they are being used for medicine. Statistically drug development is more pronounced when there has been some sort of traditional use of the plant. Some people make reference to the ‘Doctrine of Signatures’, an old medieval term which means that the plant looks like the disease or the part of the body that it should treat. For example, ginseng root looks like a little body with a head and legs and arms, so it is used as a tonic or a treatment for the whole body. Some say the sausage tree has grey, scaly skin, so it might have used to treat skin diseases. In Africa, it has been used traditionally to help with dark skin spots (solar keratosis), especially around the face. These can lead to skin cancer, so in theory the plant might be a treatment for skin cancer.

I spent my PhD trying to identify if any of the plant was bioactive. For example, the fruit or the roots or the bark or leaves of the tree. What I actually found was the fruit was bioactive against melanoma cells in vitro (in the test tube). We did a bioassay guided fractionation, and identified the actual compounds that were responsible for the activity. However, with today’s modern medicine it’s not always the magic bullet or the single compound that is the active constituent. It might be several compounds working together in synergy that are causing the desired effect. As mentioned, I think there are a lot more studies that need to be undertaken, especially with the positive results we found at King’s College, but clinical trials can take many years, and are very costly. It’s quite a conversational starter though when I arrive at Customs with several Kigelia fruit in my backpack.

Jaguar shaman in the Amazonian rainforest

What can you tell us about your research into the uses of African medicinal plants as therapeutic agents in oncology ?

I did a lot of research as part of my PhD. My professor was one of the world experts on Kigelia pinnata, the sausage tree, which has been used traditionally against malignant melanoma and solar keratosis, and my PhD thesis was a study of compounds isolated from this plant against skin cancer. I worked at Charing Cross Hospital in London, isolating the active compounds and testing on human melanoma cell lines (tissue culture). We identified several compounds that showed activity, but it can take over 10 years and up to $100M to discover a new drug, so this work is still ongoing and will take many years to create any new medicines.

You yourself are now a world expert on Kigelia pinnata. What can you tell us about it ?

Crikey, that sounds grand, but I guess there are not many people who have researched Kigelia pinnata. I co-wrote a lovely paper for Herbalgram which gives you an outline of the plant. It’s quite an amazing species which belongs to the Bignoniaceae family, which also includes the catalpa tree from South America. It contains a compound called lapachol, which was taken forward for cancer research, but it was found to be quite toxic in vivo (animal)studies and so was dropped, but I still think it’s a plant family that needs a lot more research to be undertaken. I’m hoping one day I can pick up the baton again and take this research further.

My theory is that plants used for traditional medicine make greater leads for new drug discovery as they have been used for many thousands of years, so there must be a reason why they are being used for medicine. Statistically drug development is more pronounced when there has been some sort of traditional use of the plant. Some people make reference to the ‘Doctrine of Signatures’, an old medieval term which means that the plant looks like the disease or the part of the body that it should treat. For example, ginseng root looks like a little body with a head and legs and arms, so it is used as a tonic or a treatment for the whole body. Some say the sausage tree has grey, scaly skin, so it might have used to treat skin diseases. In Africa, it has been used traditionally to help with dark skin spots (solar keratosis), especially around the face. These can lead to skin cancer, so in theory the plant might be a treatment for skin cancer.

I spent my PhD trying to identify if any of the plant was bioactive. For example, the fruit or the roots or the bark or leaves of the tree. What I actually found was the fruit was bioactive against melanoma cells in vitro (in the test tube). We did a bioassay guided fractionation, and identified the actual compounds that were responsible for the activity. However, with today’s modern medicine it’s not always the magic bullet or the single compound that is the active constituent. It might be several compounds working together in synergy that are causing the desired effect. As mentioned, I think there are a lot more studies that need to be undertaken, especially with the positive results we found at King’s College, but clinical trials can take many years, and are very costly. It’s quite a conversational starter though when I arrive at Customs with several Kigelia fruit in my backpack.

Kigelia pinnata

Kigelia pinnata

Kigelia pinnata fruit

Your first venture into therapeutic cosmetic products derived directly from plant extracts was with Dr. Jackson’s. How did that come about ?

I guess I had been observing how natural products were starting to become a global trend in cosmetics. We have a term called cosmeceuticals, which describes something that is part cosmetic – enhancing your appearance – and part pharmaceutical – giving you a desired result at the cellular level. I started to think, wouldn’t it be great if I approached the cosmetic market using pharmacognosy principles. For example, making sure that we were certain what extracts we were putting into our products, checking the quality of ingredients, making sure that we had pharmacy grade extracts and that there was no adulteration in our extracts. It’s quite common for plant extracts to be adulterated with cheaper alternatives. For example, chamomile is often adulterated with feverfew. To the naked eye, the plant and flower looks the same, but they have a whole different pharmacology. I heard once of a parsnip being used in traditional Chinese medicine as ginseng! It had been sprayed with ginseng, so tested positive, but was totally the wrong species.

So Dr. Jackson’s was born in 2008. I wasn’t quite sure if consumers were ready for this type of product, but I was wrong and it became very popular. For me it was more about keeping alive the discipline of pharmacognosy, and so we had mentions of the discipline in Vogue, GQ, Tatler and many other widely-read publications. It was quite something to bring this specialised area of study into the mainstream media. I think the beauty industry had been exposed to many ‘kitchen sink’ cosmeticians, who had started their businesses literally on the kitchen table. They were happy to find the real deal, a company founded on science and evidence-based research. I’d like to think we really forged the way for what can only now be described as the golden age of natural cosmetic products. We were very lucky for the opportunity to showcase African ingredients in our products. It really was about being at the right place at the right time for the company. Now African botanical ingredients are found in many cosmetic companies’ ingredient lists.

My husband John joined the company as the Business Development Manager, and we explored many export markets. Of course, the Asian markets really understood us as it’s very much ‘you are what you eat’ in Asia, and obviously traditional Chinese medicine has been around for over 2000 years, as has Ayurvedic medicine in India, so it was a lot easier to enter the markets there. In 2016 we had an opportunity to successfully exit the brand and then we moved to Ireland, to West Cork.

Kigelia pinnata fruit

Your first venture into therapeutic cosmetic products derived directly from plant extracts was with Dr. Jackson’s. How did that come about ?

I guess I had been observing how natural products were starting to become a global trend in cosmetics. We have a term called cosmeceuticals, which describes something that is part cosmetic – enhancing your appearance – and part pharmaceutical – giving you a desired result at the cellular level. I started to think, wouldn’t it be great if I approached the cosmetic market using pharmacognosy principles. For example, making sure that we were certain what extracts we were putting into our products, checking the quality of ingredients, making sure that we had pharmacy grade extracts and that there was no adulteration in our extracts. It’s quite common for plant extracts to be adulterated with cheaper alternatives. For example, chamomile is often adulterated with feverfew. To the naked eye, the plant and flower looks the same, but they have a whole different pharmacology. I heard once of a parsnip being used in traditional Chinese medicine as ginseng! It had been sprayed with ginseng, so tested positive, but was totally the wrong species.

So Dr. Jackson’s was born in 2008. I wasn’t quite sure if consumers were ready for this type of product, but I was wrong and it became very popular. For me it was more about keeping alive the discipline of pharmacognosy, and so we had mentions of the discipline in Vogue, GQ, Tatler and many other widely-read publications. It was quite something to bring this specialised area of study into the mainstream media. I think the beauty industry had been exposed to many ‘kitchen sink’ cosmeticians, who had started their businesses literally on the kitchen table. They were happy to find the real deal, a company founded on science and evidence-based research. I’d like to think we really forged the way for what can only now be described as the golden age of natural cosmetic products. We were very lucky for the opportunity to showcase African ingredients in our products. It really was about being at the right place at the right time for the company. Now African botanical ingredients are found in many cosmetic companies’ ingredient lists.

My husband John joined the company as the Business Development Manager, and we explored many export markets. Of course, the Asian markets really understood us as it’s very much ‘you are what you eat’ in Asia, and obviously traditional Chinese medicine has been around for over 2000 years, as has Ayurvedic medicine in India, so it was a lot easier to enter the markets there. In 2016 we had an opportunity to successfully exit the brand and then we moved to Ireland, to West Cork.

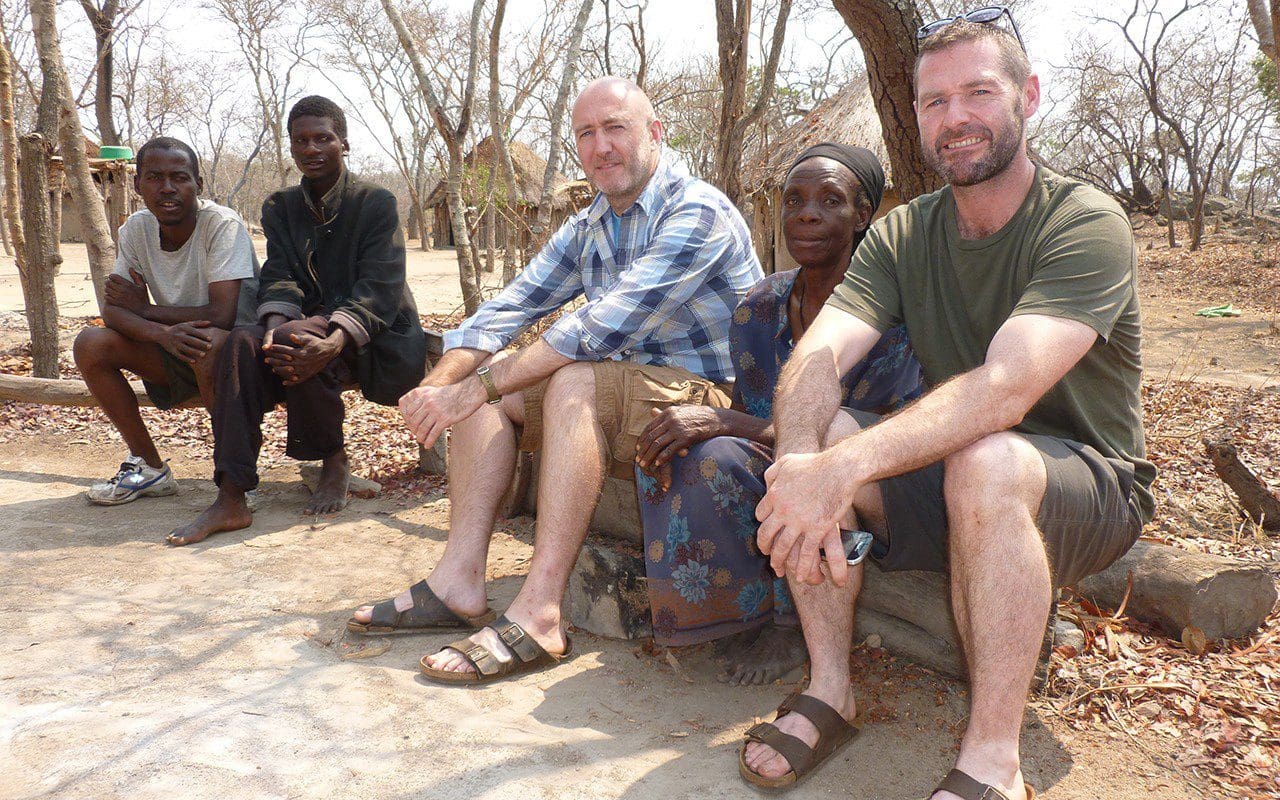

Simon and John on a field trip to Zimbabwe

Simon and John on a field trip to Zimbabwe

Steam distillation in the field in Zambezi

Can you explain the processes you had to go through to develop cosmetic products that you knew would work and the gap in the market you identified that they would fill ?

I had been thinking about making a skin cream using African products right back in 1993, when I first started seeing the health benefits of African ingredients, but it took me till 2008, when I set up my company, and then a further four years until I launched my first product in 2012. For me I was fed up with seeing all these other ‘natural’ brands launching products, but not really being natural at all. They are what we call ‘naturally inspired’ and made claim after claim, but with no real scientific knowledge being used. ‘Angel dusting’ is a term used in the industry where twenty to thirty ingredients are used in products to give it a therapeutic effect, when in reality you should never use more than 5 or 6 ingredients in a product. Less is definitely more in this case. For me the process was to identify the problem first and then work on a solution.

We have had lots of lovely testimonials from people using our products. For example, I’ve made a few oil products containing arnica and calendula, which are great for cosmetic use, but many patients with dry or thin skin after chemotherapy have said it’s the only thing that they can use on their skin. I wanted to make products that could be used by people with the most sensitive of skin conditions, especially with a lower immune system or people who wanted ‘chemical free’ products. For me the ‘gap in the market’ was offering post-chemical era natural products that actually work and contain active ingredients that are genuinely efficacious and replicable in every bottle.

I always made sure that we only made our products in GMP facilities, (Good Manufacturing Practice). We also make sure that all outsourced companies are ISO quality certified. It was very important for me to make sure that all our products were cruelty-free certified with absolutely no animal testing and were both vegetarian and vegan certified. It’s amazing how many companies make these claims, but don’t have the certification to back it up. One key thing that we do every time we develop any products is to thoroughly research any proposed ingredients. It’s all well and good introducing new species to people, but if that species is on the CITES list of endangered species then we will not take it to market.

For every ingredient we use, we have a whole process where we check the marketability of that species, whether research has been undertaken before, whether it is a commonly known ingredient, or whether it needs more research undertaken to be able to use it. Something that has been used traditionally in Africa may be seen as an exotic or novel foodstuff in Europe. So all of these considerations need to be taken into account. I guess people don’t see the amount of work that needs to be undertaken even before we set foot into the laboratory.

Since you and John moved to southern Ireland two years ago, you have been working together on a range of cosmetic products for your new venture, Modern Botany. What was the impetus behind this move and how do you find working together?

We moved here in 2016 to a little town called Schull on the beautiful wild Atlantic Coast in West Cork. It’s the most south-westerly point in Europe with the most spectacular unspoilt land and seascapes. It really is ‘Next stop America!’. John and I have been coming here regularly on our vacations and John’s family home is nearby, so we have a spiritual connection with the place and people, who are so friendly and hospitable. It has been a dream of ours to settle here and build a natural product company focusing on accessible, efficacious unisex personal care products. We are all about ‘clean and green’ beauty, so being such a clean and green environment as the West of Ireland is the perfect fit. West Cork was very much by-passed by the industrial revolution, so it is very unpolluted.

Working as a couple has its obvious challenges, but we have learned over the years to understand each other’s strong points and attributes. John is best at business development and managing relationships, while I focus on the science element of the business and innovative product development. I like to think that we complement each other in a way that’s conducive to our mutual goals. And we both love living in such a beautiful part of the world. We are even taking up a bit of kayaking and sailing, as we are so close the sea here. It’s also been great to learn more about marine pharmacognosy and local seaweed, so watch this space.

Steam distillation in the field in Zambezi

Can you explain the processes you had to go through to develop cosmetic products that you knew would work and the gap in the market you identified that they would fill ?

I had been thinking about making a skin cream using African products right back in 1993, when I first started seeing the health benefits of African ingredients, but it took me till 2008, when I set up my company, and then a further four years until I launched my first product in 2012. For me I was fed up with seeing all these other ‘natural’ brands launching products, but not really being natural at all. They are what we call ‘naturally inspired’ and made claim after claim, but with no real scientific knowledge being used. ‘Angel dusting’ is a term used in the industry where twenty to thirty ingredients are used in products to give it a therapeutic effect, when in reality you should never use more than 5 or 6 ingredients in a product. Less is definitely more in this case. For me the process was to identify the problem first and then work on a solution.

We have had lots of lovely testimonials from people using our products. For example, I’ve made a few oil products containing arnica and calendula, which are great for cosmetic use, but many patients with dry or thin skin after chemotherapy have said it’s the only thing that they can use on their skin. I wanted to make products that could be used by people with the most sensitive of skin conditions, especially with a lower immune system or people who wanted ‘chemical free’ products. For me the ‘gap in the market’ was offering post-chemical era natural products that actually work and contain active ingredients that are genuinely efficacious and replicable in every bottle.

I always made sure that we only made our products in GMP facilities, (Good Manufacturing Practice). We also make sure that all outsourced companies are ISO quality certified. It was very important for me to make sure that all our products were cruelty-free certified with absolutely no animal testing and were both vegetarian and vegan certified. It’s amazing how many companies make these claims, but don’t have the certification to back it up. One key thing that we do every time we develop any products is to thoroughly research any proposed ingredients. It’s all well and good introducing new species to people, but if that species is on the CITES list of endangered species then we will not take it to market.

For every ingredient we use, we have a whole process where we check the marketability of that species, whether research has been undertaken before, whether it is a commonly known ingredient, or whether it needs more research undertaken to be able to use it. Something that has been used traditionally in Africa may be seen as an exotic or novel foodstuff in Europe. So all of these considerations need to be taken into account. I guess people don’t see the amount of work that needs to be undertaken even before we set foot into the laboratory.

Since you and John moved to southern Ireland two years ago, you have been working together on a range of cosmetic products for your new venture, Modern Botany. What was the impetus behind this move and how do you find working together?

We moved here in 2016 to a little town called Schull on the beautiful wild Atlantic Coast in West Cork. It’s the most south-westerly point in Europe with the most spectacular unspoilt land and seascapes. It really is ‘Next stop America!’. John and I have been coming here regularly on our vacations and John’s family home is nearby, so we have a spiritual connection with the place and people, who are so friendly and hospitable. It has been a dream of ours to settle here and build a natural product company focusing on accessible, efficacious unisex personal care products. We are all about ‘clean and green’ beauty, so being such a clean and green environment as the West of Ireland is the perfect fit. West Cork was very much by-passed by the industrial revolution, so it is very unpolluted.

Working as a couple has its obvious challenges, but we have learned over the years to understand each other’s strong points and attributes. John is best at business development and managing relationships, while I focus on the science element of the business and innovative product development. I like to think that we complement each other in a way that’s conducive to our mutual goals. And we both love living in such a beautiful part of the world. We are even taking up a bit of kayaking and sailing, as we are so close the sea here. It’s also been great to learn more about marine pharmacognosy and local seaweed, so watch this space.

A field of German chamomile at Simon and John’s farm in Schull

Can you describe the ethos behind the products you are developing for Modern Botany ?

We are very excited about our latest venture. We aim to elevate the quality and standard of personal care natural products by producing 100% natural and effective, frequent-use products. Our focus here is on personal care rather than beauty/cosmetic products and we want to highlight the importance of skin health. All our products are safe and designed for people with sensitive skin conditions such as eczema and psoriasis or for pregnant mums. They are all chemical free with no parabens, petrochemicals or aluminium. We aim to educate consumers on awareness of what we put on our skin and all our products utilise the best from the natural world by creating formulations that are novel and innovative using natural ingredients that are of pharmaceutical grade extracts. This ensures the optimum therapeutic effect on your skin.

We are all about inclusivity and making easy-to-use and understandable products that are affordable and multi-purpose. We are an eco-sustainable company and all our packaging is recyclable and made in Ireland so that we can control our carbon footprint. Our aspiration is to eventually grow and process and introduce into our supply chain all of our constituent medicinal ingredients. We have been working with the agricultural department in Ireland and have these past two years been growing test crops with great results on our little farm. We want to encourage local farmers to grow flaxseed, chamomile, evening primrose, calendula and borage to start with, as all of them grow really well in the soil in our part of Ireland.

A field of German chamomile at Simon and John’s farm in Schull

Can you describe the ethos behind the products you are developing for Modern Botany ?

We are very excited about our latest venture. We aim to elevate the quality and standard of personal care natural products by producing 100% natural and effective, frequent-use products. Our focus here is on personal care rather than beauty/cosmetic products and we want to highlight the importance of skin health. All our products are safe and designed for people with sensitive skin conditions such as eczema and psoriasis or for pregnant mums. They are all chemical free with no parabens, petrochemicals or aluminium. We aim to educate consumers on awareness of what we put on our skin and all our products utilise the best from the natural world by creating formulations that are novel and innovative using natural ingredients that are of pharmaceutical grade extracts. This ensures the optimum therapeutic effect on your skin.

We are all about inclusivity and making easy-to-use and understandable products that are affordable and multi-purpose. We are an eco-sustainable company and all our packaging is recyclable and made in Ireland so that we can control our carbon footprint. Our aspiration is to eventually grow and process and introduce into our supply chain all of our constituent medicinal ingredients. We have been working with the agricultural department in Ireland and have these past two years been growing test crops with great results on our little farm. We want to encourage local farmers to grow flaxseed, chamomile, evening primrose, calendula and borage to start with, as all of them grow really well in the soil in our part of Ireland.

Locally grown borage, chamomile, calendula and evening primrose being used in Modern Botany products

Locally grown borage, chamomile, calendula and evening primrose being used in Modern Botany products

Modern Botany Deodorant & Multi-tasking Oil

Are there any plants that you are particularly interested in working with at the moment and why ?

We are working with some interesting plant species local to West Cork that have interesting medicinal properties. For instance, we are testing wild greater plantain (Plantago major) and bog cotton (Eriophorum angustifolium), both of which have traditional Celtic uses and can be used as astringents. We’re also looking at innovative methods of extraction from seaweeds such as serrated wrack (Fucus serratus) as well as Irish sphagnum moss, which both have incredible skin healing properties due to their anti-bacterial, wound-healing and moisturising capabilities and so are perfect for people with hypersensitive skin conditions.

How do you go about inventing and developing a new product and what’s on the cards for next year?

My starting point and our company ethos is to only create products that consider first and foremost what customers need. I’m not interested in just churning out the normal cosmetic range because it is marketable and commercially attractive. The process of development is more often exciting and inspiring when it’s making something where the genesis evolves from a genuine need and is also something that I myself would want to use.

For example, after we brought out our first product, I was approached by many people asking me to formulate a natural deodorant that was aluminium-free, but that also had to be an effective anti-perspirant. There are lots of natural deodorants on the market, but few that really work as an anti-perspirant. And that’s how Modern Botany Deodorant was developed, a multi-tasking product that is a deodorant, anti-perspirant and body scent. We have an exciting range of innovative 100% natural and unisex products coming on line in 2019, which include a universal wash that can be used by all the family, more varieties of deodorants, a multi-tasking healing emulsion and travel sets.

Interview: Huw Morgan/Photographs: Courtesy Simon Jackson and Modern Botany

Published 24 November 2018 We leave the garden now to stand into the winter and to enjoy the natural process of it falling away. The frost has already been amongst it, blackening the dahlias and pumping up the colour in the last of the autumn foliage. Walk the paths early in the morning and the birds are in there too, feasting on the seeds that have readied themselves and are now dropping fast.

I have combed the garden several times since the summer to keep in step with the ripening process, being sure not to miss anything that I might want to propagate for the future. The silvery awns on the Stipa barbata, which detach themselves in the course of a week, can easily be lost on a blustery day. This steppe-land grass is notoriously difficult to germinate and a yearly sowing of a couple of dozen seed might see just two or three come through. My original seed was given to me in the 1990’s by Karl Förster’s daughter from his residence in Potsdam, so the insurance of an up-and-coming generation keeps me comfortable in the knowledge that I am keeping that provenance continuing.

The seed harvest is something I have always practiced and, as a means of propogation, it is immensely rewarding. Many of the plants I am most attached to come from seed I have travelled home with, easily gathered and transported in my pocket or a home-made envelope. Seedlings nurtured and waited for are always more precious than ready-made plants bought from a nursery but I have learned the art of economy and sow only what I know I will need or think I might require if a plant proves to be unreliably perennial for me. The Agastache nepetoides, for instance, came to me via Piet Oudolf where they grow taller than me in his sandy garden at Hummelo. However, they are unreliable on our heavy soil and need to be re-sown every year. Fortunately, they flower in the same year and I can plug the gaps where they have failed in winter wet with young seedlings sown in March in the frame and planted out at the end of May.

Modern Botany Deodorant & Multi-tasking Oil

Are there any plants that you are particularly interested in working with at the moment and why ?

We are working with some interesting plant species local to West Cork that have interesting medicinal properties. For instance, we are testing wild greater plantain (Plantago major) and bog cotton (Eriophorum angustifolium), both of which have traditional Celtic uses and can be used as astringents. We’re also looking at innovative methods of extraction from seaweeds such as serrated wrack (Fucus serratus) as well as Irish sphagnum moss, which both have incredible skin healing properties due to their anti-bacterial, wound-healing and moisturising capabilities and so are perfect for people with hypersensitive skin conditions.

How do you go about inventing and developing a new product and what’s on the cards for next year?

My starting point and our company ethos is to only create products that consider first and foremost what customers need. I’m not interested in just churning out the normal cosmetic range because it is marketable and commercially attractive. The process of development is more often exciting and inspiring when it’s making something where the genesis evolves from a genuine need and is also something that I myself would want to use.

For example, after we brought out our first product, I was approached by many people asking me to formulate a natural deodorant that was aluminium-free, but that also had to be an effective anti-perspirant. There are lots of natural deodorants on the market, but few that really work as an anti-perspirant. And that’s how Modern Botany Deodorant was developed, a multi-tasking product that is a deodorant, anti-perspirant and body scent. We have an exciting range of innovative 100% natural and unisex products coming on line in 2019, which include a universal wash that can be used by all the family, more varieties of deodorants, a multi-tasking healing emulsion and travel sets.

Interview: Huw Morgan/Photographs: Courtesy Simon Jackson and Modern Botany

Published 24 November 2018 We leave the garden now to stand into the winter and to enjoy the natural process of it falling away. The frost has already been amongst it, blackening the dahlias and pumping up the colour in the last of the autumn foliage. Walk the paths early in the morning and the birds are in there too, feasting on the seeds that have readied themselves and are now dropping fast.

I have combed the garden several times since the summer to keep in step with the ripening process, being sure not to miss anything that I might want to propagate for the future. The silvery awns on the Stipa barbata, which detach themselves in the course of a week, can easily be lost on a blustery day. This steppe-land grass is notoriously difficult to germinate and a yearly sowing of a couple of dozen seed might see just two or three come through. My original seed was given to me in the 1990’s by Karl Förster’s daughter from his residence in Potsdam, so the insurance of an up-and-coming generation keeps me comfortable in the knowledge that I am keeping that provenance continuing.

The seed harvest is something I have always practiced and, as a means of propogation, it is immensely rewarding. Many of the plants I am most attached to come from seed I have travelled home with, easily gathered and transported in my pocket or a home-made envelope. Seedlings nurtured and waited for are always more precious than ready-made plants bought from a nursery but I have learned the art of economy and sow only what I know I will need or think I might require if a plant proves to be unreliably perennial for me. The Agastache nepetoides, for instance, came to me via Piet Oudolf where they grow taller than me in his sandy garden at Hummelo. However, they are unreliable on our heavy soil and need to be re-sown every year. Fortunately, they flower in the same year and I can plug the gaps where they have failed in winter wet with young seedlings sown in March in the frame and planted out at the end of May.

Agastache nepetoides

Over the years, as much by trial and error as by reading about the requirements and idiosyncrasies particular to each plant, I have learned the rules. The Agastache for instance will not germinate if the seed is covered, so they will fail to appear spontaneously in the garden if you mulch or sow and then cover the seed, as I usually do, with a topping of horticultural grit. The seed needs light and should just be gently pressed into the surface so that they can be triggered. The Agastache seed keeps well and is easily sown in spring, but the viability of seed is different from plant to plant. Primula vulgaris gathered and sown directly a couple of years ago saw seedlings germinate readily within a month that same summer. Last year I was busy and waited until September to sow, but the seed had already begun to go into dormancy, an inbuilt mechanism to save it in a dry summer. The overwintering process of stratification, which will unlock dormancy with the freeze, thaw, freeze, saw the seedlings germinate the following spring. The plants consequently took a whole six months longer to get them to the point that I could plant them out into the hedgerows, but I learned and will save myself that delay come the future.

Agastache nepetoides

Over the years, as much by trial and error as by reading about the requirements and idiosyncrasies particular to each plant, I have learned the rules. The Agastache for instance will not germinate if the seed is covered, so they will fail to appear spontaneously in the garden if you mulch or sow and then cover the seed, as I usually do, with a topping of horticultural grit. The seed needs light and should just be gently pressed into the surface so that they can be triggered. The Agastache seed keeps well and is easily sown in spring, but the viability of seed is different from plant to plant. Primula vulgaris gathered and sown directly a couple of years ago saw seedlings germinate readily within a month that same summer. Last year I was busy and waited until September to sow, but the seed had already begun to go into dormancy, an inbuilt mechanism to save it in a dry summer. The overwintering process of stratification, which will unlock dormancy with the freeze, thaw, freeze, saw the seedlings germinate the following spring. The plants consequently took a whole six months longer to get them to the point that I could plant them out into the hedgerows, but I learned and will save myself that delay come the future.

Molopospermum peleponnesiacum

As a rule the umbellifers tend to have a short life and the seed does not keep, so I sow my giant fennel, Astrantia and Bupleurum as soon as the seed is ripe and overwinter it in the cold frame. This year, for the first time. I have sown Molopospermum peleponnesiacum and, though it is a reliable perennial, I am keen to see if I can rear some youngsters. This ferny-leaved umbel is early to rise and I love it for the gloss and laciness of its foliage and the horizontality of its lime green flowers. I have it amongst my Molly-the-Witch peonies and their early presence together is a good one. I’m also simply curious to learn more about the life cycle of this European umbel, as I find I understand a plant better if I know how long it will take to become a parent and what it takes to get it to the point of seeding and germinating successfully.

Molopospermum peleponnesiacum

As a rule the umbellifers tend to have a short life and the seed does not keep, so I sow my giant fennel, Astrantia and Bupleurum as soon as the seed is ripe and overwinter it in the cold frame. This year, for the first time. I have sown Molopospermum peleponnesiacum and, though it is a reliable perennial, I am keen to see if I can rear some youngsters. This ferny-leaved umbel is early to rise and I love it for the gloss and laciness of its foliage and the horizontality of its lime green flowers. I have it amongst my Molly-the-Witch peonies and their early presence together is a good one. I’m also simply curious to learn more about the life cycle of this European umbel, as I find I understand a plant better if I know how long it will take to become a parent and what it takes to get it to the point of seeding and germinating successfully.

Paeonia delavayi

My Paeonia delavayi are the grandchildren of an original plant I grew from seed I collected when I was nineteen and working at the Edinburgh Botanic Gardens. The plants in the garden have started to lose whole limbs this year, which I am putting down to the heat, but it could just as easily be honey fungus. Having a few youngsters in the background is good insurance, but I am sowing the seed fresh because peony seed needs a chill and sometimes two winters before growth appears above ground. The first year is all about the formation of roots so, as a general rule, I never throw a pot of seed out for two years just in case.

Paeonia delavayi

My Paeonia delavayi are the grandchildren of an original plant I grew from seed I collected when I was nineteen and working at the Edinburgh Botanic Gardens. The plants in the garden have started to lose whole limbs this year, which I am putting down to the heat, but it could just as easily be honey fungus. Having a few youngsters in the background is good insurance, but I am sowing the seed fresh because peony seed needs a chill and sometimes two winters before growth appears above ground. The first year is all about the formation of roots so, as a general rule, I never throw a pot of seed out for two years just in case.

Asclepias tuberosa

This is the first year I have grown the tangerine milkweed, Asclepias tuberosa, and would like to get to know it better. It is said to suffer from winter wet, which is a given living where we do in the West Country, so my seed sowing is insurance again and a means of bulking up the little group I have amongst my black-leaved clover. The seed is exquisite, the claw-like pods rupturing on a dry day to spill their silky contents on the breeze. Reading up reveals that the seed also needs winter stratification, so I have sown it now in a lean, gritty compost to ensure it is free-draining and that the seed doesn’t sit wet. A gritty seed compost will ensure the seedlings search for nutrients and grow a good strong root system once they have germinated in the spring. I prefer to top dress with grit rather than soil to inhibit moss and algae build-up, which can cap the pots if they are sitting around for a while in the frame.

Asclepias tuberosa

This is the first year I have grown the tangerine milkweed, Asclepias tuberosa, and would like to get to know it better. It is said to suffer from winter wet, which is a given living where we do in the West Country, so my seed sowing is insurance again and a means of bulking up the little group I have amongst my black-leaved clover. The seed is exquisite, the claw-like pods rupturing on a dry day to spill their silky contents on the breeze. Reading up reveals that the seed also needs winter stratification, so I have sown it now in a lean, gritty compost to ensure it is free-draining and that the seed doesn’t sit wet. A gritty seed compost will ensure the seedlings search for nutrients and grow a good strong root system once they have germinated in the spring. I prefer to top dress with grit rather than soil to inhibit moss and algae build-up, which can cap the pots if they are sitting around for a while in the frame.

Dianthus carthusianorum (in second image with Achillea ‘Moonshine’)

Although I like to sow most of my hardy plants in the autumn to avoid storing them when they could be beginning their journey, I like a few in hand to simply scatter about and help in the process of naturalising where I want my plants to mingle. The Dianthus carthusianorum are this year’s project, and so I am scattering seed at the tops of my dry banks where I hope they will take in the most open parts of my wildflower slopes by the house. A cast of thousands is easily made up in a handful, but it takes only one to begin a colony.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 17 November 2018

Dianthus carthusianorum (in second image with Achillea ‘Moonshine’)

Although I like to sow most of my hardy plants in the autumn to avoid storing them when they could be beginning their journey, I like a few in hand to simply scatter about and help in the process of naturalising where I want my plants to mingle. The Dianthus carthusianorum are this year’s project, and so I am scattering seed at the tops of my dry banks where I hope they will take in the most open parts of my wildflower slopes by the house. A cast of thousands is easily made up in a handful, but it takes only one to begin a colony.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 17 November 2018 In 2015 I was approached to work as the landscape designer for a new extension at the Garden Museum. The renovations were extensive and it was the second phase of the project for Dow Jones Architects. The first, in 2008, had been to create a series of freestanding structures that moved lightly through the heritage building. This final push would see a new extension reaching out into the garden to create spaces for education, events and a new cafeteria.

The plan for the extension sailed over the footprint of the old knot garden which previously occupied the site, to enclose a new courtyard where the tombs of the Tradescants (father and son) and Captain Bligh take centre stage. The achievements of these three men provided a strong brief for the garden, which reflects their pioneering spirit as adventurers, plant hunters and educators. The Tradescants, once residents of Lambeth, had conceived their garden as a reflection of Eden and so the new cloister was also intended to be a place of sanctuary, where the seasons are brought into close perspective in the centre of the city and the planting is the focus of learning.

We pondered for some time over the removal of the well-loved knot garden, which Lady Salisbury had designed for the museum in 1980, three years after it first opened as the Museum of Garden History. Initially we worked up a series of iterations to abstract the knot garden to see if its memory could be glimpsed in the new design, but the architecture required a more confident forward-looking approach to move the garden, with the museum, into a clearly defined, bold new chapter. However, drawing from the existing sense of place was also important, so the ledger stones from the old graveyard and the bricks from the knot garden were integrated into the path that creates a frame from which to look into the planting. In the corner, where the tombs were close to the path, we extended its reach to allow closer observation of the detailed carvings and inscriptions. An old mulberry and an arbutus were retained in the new design, while an old fig and medlar were carefully moved to beds at the other end of the church. The street-side plane trees, which are protected and provide the museum with its leafy, woodland feeling, were able to have the building so close thanks to a piling system which floats the extension carefully over their root plates.

The street-side planting beneath the London Planes with Euonymus planipes on the left

The street-side planting beneath the London Planes with Euonymus planipes on the left

Aralia cordata, Hakonechloa macra and Anemone x hybrida ‘Honorine Jobert’

Aralia cordata, Hakonechloa macra and Anemone x hybrida ‘Honorine Jobert’

Rubus thibetanus ‘Silver Fern’

Rubus thibetanus ‘Silver Fern’

Viewed from four sides (through glass on three and an open, covered walkway on the fourth) the courtyard garden – called the Sackler Garden after a generous donation from the Sackler Foundation – would become a point of focus within the cloistered enclosure. The new glazed walls would also enhance the London microclimate and help buffer the garden from the wind that uses the River Thames as a corridor in this location. With the exploits of the Tradescants as inspiration, it was a small step to imagine this courtyard as a giant Wardian case – an aquarium-like structure invented in the 19th century to transport exotic and delicate new plant discoveries long distances by sea in a protected environment. The glassy cloister, our metaphorical Wardian case, allowed us to present a garden of curiosities and treasures.

Though an oasis, as a space it is far from hermetic. The planting continues on the street side of the café beneath the planes with a shady carpet of hardy evergreens and woodlanders including Hakonechloa macra and Epimedium sulphureum. A specimen Euonymus planipes was planted to frame the cafeteria door and emerging perennials such as Danae racemosa, Aralia cordata and white persicaria and wind anemone provide the planting with seasonal flux and help make the connection to the green world within. From the street the transparent walls of the café allow an intriguing glimpse of the jungly courtyard planting.

Looking into the cafe across the woodland planting from the street

Looking into the cafe across the woodland planting from the street

The courtyard garden can be seen from the street through the glass walls of the cafe

The courtyard garden can be seen from the street through the glass walls of the cafe

As the courtyard is a deliberately acute focus, it was important that it be a dynamic space that works on every day of the year. When choosing the plants, I felt it was important to continue the spirit of discovery exemplified by the Tradescants and for the plants to tell a story of horticultural history. I also wanted the composition and plant choices to capture the magic of an 18th century botanical engraving and key into the gothic mood of the churchyard and its tombstones.

Modern day plant hunters, such as Sue and Bleddyn Wynn-Jones of Crûg Farm Plants helped provide us with some of the curiosities. Fatsia polycarpa, a rarely seen castor oil plant with deeply divided, elegant fingered foliage, and a Schefflera from Taiwan, complete with precise location notes to bring their provenance to life. Nick Macer of Pan-Global Plants also provided us with some of his wild collections. A giant foliage Dahlia from a trip to Mexico, and flowering gingers for points of exotic interest. I wanted the planting to feel eclectic – a collection – and the exotic edge was important to conjure the feeling of awe and wonder that must be felt by all plant hunters. Canna x ehmannii and Tetrapanax papyrifer have done this at scale and made an immediate impact, whilst more demure curiosities such as Disporum cantoniense ‘Night Heron’ and Epimedium washunense ‘Caramel’ provide the detail once you start to look deeper.

It was of prime importance to the museum that the garden provided a centre of horticultural excellence and the planting has been layered to create an ecosystem where each component in the composition provides a microclimate for its neighbours. The layering has also allowed the play of form and texture to work in combination and, importantly, for the sequencing over the course of the year to reveal change so that the garden is different each time that you visit.

The Sackler Garden at the centre of the new extension. William Bligh’s tomb is in the centre, that of the Tradescants can just be seen on the far right

The Sackler Garden at the centre of the new extension. William Bligh’s tomb is in the centre, that of the Tradescants can just be seen on the far right

The layered planting includes, from left, Canna x ehemannii, Dryopteris erythrosora and Equisetum hyemale. Behind is a seed-collected species Dahlia from Pan-Global Plants. The groundcover is Geranium maccrorhizum ‘White Ness’, a 20th century discovery.

The layered planting includes, from left, Canna x ehemannii, Dryopteris erythrosora and Equisetum hyemale. Behind is a seed-collected species Dahlia from Pan-Global Plants. The groundcover is Geranium maccrorhizum ‘White Ness’, a 20th century discovery.

Canna x ehemannii

Canna x ehemannii

Nandina domestica and Astelia nervosa

Nandina domestica and Astelia nervosa

On the left Tetrapanax papyrifer with Astelia nervosa beneath and Rubus lineatus to the right. Behind are a Schefflera species from Crûg Farm Plants with Nandina domestica

On the left Tetrapanax papyrifer with Astelia nervosa beneath and Rubus lineatus to the right. Behind are a Schefflera species from Crûg Farm Plants with Nandina domestica

Nandina domestica has been planted around the tombstones to reflect its auspicious use as a welcome plant in China, but look carefully and in amongst its stems, like the layers in a rainforest, there is a mingling. Pewter Astelias from the Chatham Islands, delicate maidenhair ferns, the Australian violet, Viola hederacea, and black-leaved Ophiopogon nigrescens in their shadows. I wanted the garden to have plants that had a recognisable use amongst the curiosities too. Wild strawberries, that once would have grown locally in Lambeth, alongside Meyer lemons and passionfruit to remind us how we too often take the provenance of our food for granted.

Having just completed its second summer, the garden is settling in and taking shape in the careful hand of Matt Collins, the museum’s head gardener, a horticultural trainee and a number of volunteers. A planting of deliberate complexity needs a well-informed eye to keep it looking good and it is a delight to return and to see it evolving. The potentially invasive Equisetum hyemale is kept in check and in its place to score its vivid green vertical and exotic climbers scale the cloister pillars.

It has been a privilege to be part of this exciting new chapter and now also to help in developing the next. On Thursday this week the Garden Museum announced Lambeth Green, a new initiative to turn St. Mary’s Gardens alongside the Museum into a community hub, a village green for Lambeth, and also to reach its green tentacles further out into the streets to reconnect to the river and nearby Old Paradise Gardens. With the new incarnation of the Museum as a catalyst, it is now easy to see these exciting possibilities being realised.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photos: Huw Morgan Published 10 November 2018

I have just returned from the South Tyrol where we are helping to heal the scars of construction and seat a new house back into a precipitous mountainside. This north-eastern province of Italy feels more Austrian than Italian and the two-hour drive from Verona plunges you deep into a valley as the Dolomites rise up around you. The spa town of Merano sits at the end of the valley and the slopes that come down to meet the town are farmed proudly and intensively by the locals. Though there was already snow on the peaks, every ledge and terrace up to the treeline was striped with fruit trees. Figs to the lower slopes and then apples, pears, apricots and cherries in immaculate cordons criss-crossing the contours. Beautifully constructed chestnut pergolas sailed over the terraces to make the fleets of vines easily pickable and, in the gulleys that became too steep, the yellowing of the chestnut trees marked their presence at the base of the oak woods above them. Our client helped to make our stay that much more memorable with a meal at a typical Tyrolean eatery on the last night. A winding, single-track road into the orchards threw us off course more than once, but we eventually found the farmhouse, sitting square and noble with the view of the town below. We were welcomed warmly by the family who have occupied this farm for more than seven hundred years and invited into a beautifully simple wood-panelled room. Shared farmhouse tables with chequered tablecloths and lace-covered pendant lights concentrated the experience and a tiled floor-to-ceiling stove sat in the corner of the room to enhance the autumnal feeling. Our host came to the table, offering speck and drawing up a chair beside us to cut and portion it carefully, as he explained the nature of the meal to come. The speck was his own and he told us how it was smoked daily over the course of three months with the prunings from his vines and apple trees. A perfectly portioned apple, rosy as in a fable, sat on the chopping board as a complement, together with schüttelbrot, a South Tyrolean crispbread flavoured with caraway seed. A jug of this year’s new wine, the first of several, helped to lubricate the feast that was to follow. Next came the knödel. Two portions, one red and made of beetroot, the other yellow which, on tasting, we discovered were made with swede, both drenched in a sauce of melted butter and grated parmesan. A meaty plate of home made blood sausage and belly pork on a bed of sauerkraut came next, with more knödel, this time flecked with chopped speck. Finally, a round of hot, charcoal-roasted chestnuts made it to the table. A large cube of butter and schnapps infused with grape skin served to counteract their mealiness and, as we peeled them together, our fingers blackened, I couldn’t help but feel that this same autumn meal must have been eaten in this room for generations. Beetroot ‘Egitto Migliorata’

Beetroot ‘Egitto Migliorata’

INGREDIENTS

Knödel

250g beetroot

1 small onion, finely chopped, about 50g

1 clove garlic, finely chopped

1 tablespoon butter

70g coarse breadcrumbs

30g hard goat cheese or pecorino, finely grated

1 small egg

30-50g plain flour

Small bunch flat leaf parsley, about 1 tablespoon finely chopped

Small bunch dill fronds, about 1 tablespoon finely chopped

Salt and pepper

Sauce

8 tablespoons buttermilk

1 tablespoon soured cream

1 tablespoon freshly grated or creamed horseradish

1 tablespoon olive oil

1 tablespoon lemon juice

Salt

Finely grated hard goat cheese, finely chopped parsley and dill fronds to serve.Serves 2

METHOD It is worth saying that to get the best result you must use breadcrumbs made from the best bread you can get, preferably sourdough, and that the breadcrumbs should be quite coarse. It is also said that the staler the breadcrumbs, the better the knödel. If you can’t get hold of buttermilk use just soured cream or crème fraiche. Heat the oven to 180°C. Wrap the beetroot tightly in foil and bake for 30 minutes to an hour depending on size, until they are soft. Unwrap and leave to cool. Rub the skins off under cold running water. Grate coarsely and put into a mixing bowl. Melt the butter in a small lidded saucepan over a moderate heat. Put in the onion and garlic, stir to coat, then put the lid on the pan and reduce the heat to low. Sweat the onion for about five minutes until it is soft and translucent, but not coloured, stirring from time to time. Remove from the heat, allow to cool, and add to the beetroot. Add all of the remaining dumpling ingredients, apart from the flour, to the beetroot and onion. Stir until all is well combined. Season with salt and pepper. Add the flour, starting with 30g. The dough should remain soft, but start to come together in the bowl. If the mixture seems too wet add flour a little at a time until the right consistency is reached. Do not be tempted to add more flour or the dumplings will be gluey. Leave the mixture to sit for 15 to 20 minutes while you bring a deep pan of water to the boil and make the sauce, by putting all of the sauce ingredients into a bowl and whisking together until emulsified. When the water comes to the boil, turn down to a gentle simmer. Using a knife or spoon divide the dumpling mixture into quarters. Wet your hands with cold water and then take a quarter of the mixture and quickly shape it into a ball. Repeat with the remaining dumpling mixture. Gently lower the dumplings into the hot water, being careful not to burn your fingers. The dumplings will sink. Using a slotted or perforated spoon stir them very gently from time to time to stop them sticking to the bottom of the pan. Cook for 8 to 10 minutes until they float, when they are ready. Carefully remove the dumplings from the pan with a slotted spoon and allow as much water as possible to drain away. Spoon the sauce onto two plates and place two of the dumplings on each plate. Scatter the herbs and cheese over and serve immediately while still hot. Words: Dan Pearson / Recipe and photographs: Huw Morgan Published 3 November 2018A chill wind is pushing the weather through the valley, tossing the garden and tearing the colour from the trees. This late autumn feeling is distinct for being burned clear into our memory of arriving here exactly eight years ago. We sat on the banks below the house wrapped in blankets on the same chairs that, just the day before, were out on the deck in Peckham, where we had willingly left a well-loved garden behind. The feeling of the new and the excitement of a prospect is still very clear to me and the anniversary has given us cause to ponder all that has happened since. The unloved land, grazed to the bone and up to the very foundations of the buildings, is now softened by growth. We look up the slopes into a little wood – our first planting project that winter, where an empty field gave way to a broken hedge – and down onto a new orchard where the trees are fruiting and casting their own proper shade. It is time marked very tangibly in growth.