As regular readers know, every year we experiment with a new round of tulips, choosing ten or so varieties and thirty of each to expand a palette of favourites. When we moved here initially we grew them in orderly rows and, with room here to have plenty, we cut them liberally and with abandon for the house. Each year we have selected a different colour palette, diving off into the deep end with varieties that appealed in an image and usually going back to a couple that we know from the past for the joy of familiarity or the experiment of a new partner.

It was picking the flowers and feeling uninhibited about doing so that started to open up a new way of looking at these extraordinary flowers. Mixed together and evolving as the bunches aged, they leaned and reached for the light and grew into each other in a way that was impossible to replicate in the order of the cutting garden. We enjoyed the freedom in a bunch with forms and colours apparently juxtaposed and colliding unexpectedly. So, when the new kitchen garden was completed three years ago, we started to grow them differently, dispensing with the order of rows and instead throwing the bulbs together so that their combinations were random. Strictly judged in our initial selection, so that we have control over the aesthetic, but massed together with six or eight inches between the bulbs, we have found joy in the riot.

Every year the outcome has been different for the choice and juxtaposition of varieties. Choosing forms that span the tulip season has assured us a smattering of earlies which age as they collide with the next in line and so on. Tulips last a long time and change as they move from bud to fully blown flower, so the combinations evolve from day to day as they rearrange themselves in height and colour saturation. We aim for a variety of flower shapes and sizes and tend to choose forms with good long stems, those with shorter stems must have something extra in the flower to justify their presence. We cut them randomly as the mix evolves to refine more intended bunches for the house. In a cool spring the process of looking and cutting and then living with the flowers inside again can last almost six weeks. As the mix moves towards its climax there is usually a moment when you stop looking at the individual and take in the field of colour as if it were a textile or an abstract painting. It is a point of saturation and satiation and usually the point at which it becomes time to move on to the summer garden.

We move the tulips around from beds to bed each year to avoid Tulip Fire occuring more than it should. Last year, with a wet spring, it was bad and I am guessing that our West country damp doesn’t help, for there is almost always a reappearance. This year the tulips made the pumpkin bed their home and the dry spring has seen us through, removing the odd plant that has shown the twist and distortion of the Fire. When the bulbs are finished I must confess to digging and discarding them to start again next year, but the best and strongest varieties that show signs of resistance will be found a more permanent home in a dry part of the garden where they will be less tested by our heavy ground.

In order of flowering our selection this year was;

Very early to flower in late March. Good strong stem. The coral pink flower intensifies in colour as it ages. 50cm.

Unusual shade of brownish maroon with fine dark stem. Perfect egg-shaped flower. Very elegant cut flower. 40cm.

An old favourite, although threatened with being taken off the market in favour of newer varieties. Vibrant scarlet with a heavy bloom to the new petals. 25-30cm.

Another we return to from time to time. Another elegant flower in a restrained shade of cardinal red. Upright grower. Strong stem. 30cm.

A large lily-flowered tulip in an appropriately named shade of wine. However, the flower seems too large for the stem length and the petals too large for the flower, looking disturbingly like livid tongues. 50cm.

A substitute by the supplier for Tulip ‘Fantasy’, a deep pink parrot tulip with green veining, this also has variegated foliage which is usually a complete no-no. Although brighter in the mix than intended it made a dramatic cut flower. 40cm.

A tall, very elegant fringed tulip of deepest burgundy. Very upright, making it a little stiff when cut. 45cm.

Our very favourite parrot tulip which we return to again and again. Very tall for a parrot tulip. Slender stemmed and with smallish, deeply cut flowers with a heavy bloom. 55cm.

A new variety for us, which we wanted try despite the off-putting name. A semi-parrot in a shade of deep old rose. The shortish petals twist and turn which give it the appearance of a pair of the eponymous frilly undies. 50cm.

Not burgundy at all, but an eye-catching shade of shocking pink. A good strong tulip with a straight stem. 60cm

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 4 May 2019

Wishing you a happy Easter.

We are taking two weeks off, to work in the garden and make the most of spring.

See you in early May.

These snowy boughs

Neither cold nor thawing

Declare spring’s advent

Words & photograph: Huw Morgan

Published 13 April 2019

Stirring early from the dark mud, whilst almost everything else is sleeping, come the marsh marigolds. They were with us at the beginning of March this year, alone and lush and startlingly gold for their precociousness. Taking over just as the snowdrops are dimming, Caltha palustris is more than welcome when you are pining for momentum, their cupped blooms glossy and facing upwards to catch sunshine. Their growth is fast and out of kilter with the slowly waking world around them, their limbs arching out and splaying away from the rosette of lush foliage. Fat buds weigh the long flowering limbs, which hover just above water as if they feel their own reflection.

I started our colony here with a little clutch of plants that our neighbours gave me from their wet alder woodland. The deer population – or their passage through the woods – must have changed since then, because the colony has diminished through increased grazing. Where there is a decline in one place, there is often a countermove in another and I have made it my business to give them a place here at the head of the ditch, where a constantly running stream animates the crease between our fields.

When we came here the ditch was just that, a place that was fenced off to keep the cattle from getting lost in the mud and where bramble had taken over from barbed wire. We have cleared it since then, letting the hazels grow out and uncovering a surprisingly pretty rivulet of water that sparkles when it is free of growth in the winter.

Four years ago I planted a batch of 40 plugs, which arrived from British Wild Flowers just as the winter was turning to spring. Marshland plants and aquatics are best planted with the opening of the growing season rather than at the close, so that their roots can take advantage of soil that is rapidly warming rather than doing the opposite in the winter months. Planting plugs is always easy with a thumb sized knot of roots easily inserted with a dibber, but you have to have faith if you are introducing them into a ‘natural’ situation, for in no time the plants are overwhelmed by the growth of established natives and you loose them from sight for the summer.

I followed the mud and the smell of dormant water mint as I planted, pushing the plugs into soil that was almost liquid and avoiding the areas that I could see would dry out as soon as summer came. Caltha will grow in shallow water too, but the margins that maintain constant moisture are their preferred domain. They are surprisingly tolerant of competition and, to prepare for it, their early start means that they have set seed and the rosette has fed all it needs to before being plunged into shadow of wild angelica, meadowsweet and hemlock water dropwort. In summer they go into a resting period, the lush foliage of spring collapsed but not dormant, taking in all it needs to keep things ticking over.

The spring after planting I followed the watercourse to retrace my steps from the year before. Given the fecundity of the summer growth here, it came as no surprise that just one plant had made enough energy to flower, but to my delight I found the rest of the 40, which in three years were all flowering and tracing a line of early gold, providing first forage for the bees, whose hive sits on the ground immediately above them.

This year I have found the first seedlings, which have tucked themselves close to their parents in the mud where the conditions are controlled by the lush growth above them. The seed, which is heavy, germinates where it falls and does not move very far, but I imagine if it falls into water, it will wash and tumble a fair distance before finding purchase. To help in this process, and now that the youngsters are proof of the fact that they have found a niche, I have extended the colony downstream. Another forty plants went in this winter, just as the first signs of growth were showing, stopping and starting so that they look like they have found their own way in the watery margins.

A bridge now crosses the water where we connect from the garden to the rise of The Tump and I increased the Caltha to either side here so that we can look down on them and meet their upward-facing gaze. Looking downstream from the bridge, I can already imagine the colony extending its reach still further, finding the hollows and the wet puddles of mud that provide it with the opportunity of an early start and us the joy of seeing these wild plants naturalise.

Words: Dan Pearson/Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 6 April 2019

I have been away for work for just over a week, a week that has seen the buds on the plum orchard break into luminous clouds of flower. I was aware when we scheduled this time away that it would be a small torture knowing that this long-awaited moment was going on without me, but there is nothing like returning to change.

To add to the tension of being away, at the last minute my return plane was rerouted via Beijing for a sick passenger when we were half way across China. It was well after midnight when I pulled into the drive at home. There was a chill in the night air but there to greet me, pale and luminous at the bottom of the steps, were the poised chalices of Arum creticum. I had noted the slim green fingers and promise of flower as I’d left and the time I’d spent away was marked in their transformation.

Rolled back to open throats to the sky, the twist of their creamy sheaths would surely inspire a milliner. Fresh, primrose yellow with a darker, yolky spadix they sit well against the glossy foliage which has been good all winter, but will soon be gone as the energy is drained once the flower is pollinated. Where many arums attract flies with a foul or animal smell, Arum creticum has a sweet perfume that hangs gently in the air on a still, sunny spring day.

Arum creticum is a plant that has an exotic feeling about it, without making you fear for its hardiness. I have yet to see it in its native habitat in Greece, but have read that it is found in cool crevices in open, deciduous woodland. Though it is perfectly hardy here, rising early in a countermovement to flush fresh green leaf in autumn, it prefers a position where it can bask in winter sunshine and a leaf-mouldy soil that holds moisture in winter and dries out in summer once the plant is dormant.

I moved the rhizomes to Hillside a couple of years ago from a clump that we had growing in the studio garden in London at the base of a south-facing wall. They flowered well for the first couple of years, but my desire for privacy has rapidly seen this one-time hot spot become shadowy, as the limbs of Cornus ‘Gloria Birkett’ have reached up and out to dapple the garden. As the shade made itself felt, so the arums went into a holding pattern of leaf and no flower to let me know that, although in Greece life on the woodland floor might be tolerable, it was not so here where the intensity of spring light is so much less reliable.

I dug up the rhizomes just as the plants were going into dormancy and put them against an east-facing wall where they have all the light they need, but also, importantly, shelter from our prevailing westerlies. I’ve noticed that I have left some youngsters behind in London, for the rhizomes divide easily, but I will gather them up in the next couple of weeks and bring them to Somerset to extend my little colony.

Being one of the first parts of the planted garden you meet as you approach the house, the companions to the arum are also early risers. A fellow from the same country in Ferula communis ssp. glauca, a fellow to the fennel’s featheriness in the fern-leaved Paeonia tenuifolia and the early species wallflower Erysimum scoparium, a native of the Canary Islands. The simplicity and architecture of the arum sits well against the filigree foliage and the mutual break with winter could not make a better welcome.

Words: Dan Pearson/Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 30 March 2019

Raymond Lewis, the farmer who lived here before us, was born in this house shortly after his parents moved here in the early 1930’s. Although he raised cattle, his parents had been market gardeners and it is our nearest neighbour, Glad, who has been the fount of all knowledge regarding how the land here was used before we arrived. She too was born here, in the house just above ours on the other side of the lane, and went to school with Raymond. She has a prime view over our slopes.

It was she who told us that we were planting our new orchard on the site of the Lewis’ old orchard, that the hollies by the Milking Barn were harvested each year for wreaths destined for the Christmas Market in Bath and that the extra-scented, large violets we found growing everywhere were wrapped in leaves and tied with cotton for spring posies. When we expressed amazement at finding ‘wild’ gooseberries and redcurrants in our farthest hedgerow, Glad said that it bordered the field where the soft fruit had been grown and so we realised that they had arrived through the actions of thieving birds.

Another piece of growing history she imparted was to do with the ramshackle shed half way down the field in front of the house. We had been charmed by this little structure from the first time we saw it, but couldn’t work out what it had been used for. Made from a motley collection of wood and reclaimed corrugated tin sheeting and open on two sides it is barely high enough to stand up in. It evidently hadn’t been used by Raymond’s cattle, and it was too far from the house to have had any obvious purpose such as a vegetable or wood store. The clue to its use was revealed the winter after we arrived, when clearing the mess of bramble from the hedge that runs up behind it.

There in the undergrowth were a dozen or so terracotta rhubarb forcers. Unfortunately all but a couple were broken beyond use, but it was suddenly clear what the little shed had been used for. We asked Glad at the first opportunity and she confirmed that it had been ‘the rhubarb forcing hut’, which is how we have referred to it ever since. We have often imagined Mr. and Mrs. Lewis in there in deepest winter, inspecting the covered crowns by candlelight (as they still do in the Yorkshire rhubarb triangle to prevent the stalks colouring) and then carefully harvesting armfuls of the pale pink stems to take to market. Now it provides shelter for the sheep that graze our pastures and has sometimes protected us from sudden summer downpours when the water runs off the roof in sheets.

We have three varieties of rhubarb in the Kitchen Garden here which take us through spring and early summer; Timperley Early, Champagne and Victoria. The first is, not surprisingly, said to be the earliest, and has always been so for us. We have found it possible to force it for stems in February. The other two are later and tend to come together if left uncovered, but by forcing one of them and leaving the other – on a yearly rotation – we can have rhubarb until June. Beyond that and it can become a little long in the tooth and green to eat fresh, but is still perfectly serviceable for jam. When forcing rhubarb it is important to only cover part of the crown and, when ready to harvest, to take the slenderest stems and leave the strongest to feed that part of the plant for the future. To allow it to rebuild its reserves you should then choose a different part of the crown to force the following year.

The flavour of forced rhubarb is so subtle that it needs the simplest of treatments to show it off to its best advantage. Most often I just roast it and serve with a creamy accompaniment of buttermilk pudding, pannacotta or, simplest, a mixture of whipped double cream and creme fraiche. I find orange, the customary partner of rhubarb, overwhelms this early season delicacy. However, judicious use of thyme or rosemary adds an unexpected counterpoint that suits this fruit that is actually a vegetable. It also has an affinity with the aniseed used here, but it’s not essential, so leave it out if you prefer.

The pastry is based on a recipe by Alice Waters of Chez Panisse, and is a fast and easy way to achieve a deliciously flaky result. Its success relies on using the best quality butter and flour and the very lightest of touches to ensure the pastry stays as cold as possible. If you are using open grown rather than forced rhubarb you will need to increase the quantity of sugar in the filling by at least 25g, depending on how tart you like your rhubarb.

200g plain flour, Tipo 00 preferably

150g unsalted butter

1 teaspoon icing sugar

A large pinch of fine sea salt

8 tablespoons iced water plus a couple more

500g forced rhubarb, trimmed weight

75g caster sugar

1/2 teaspoon vanilla essence

3 tablespoons ground almonds

1 teaspoon aniseed

2 teaspoons icing sugar

1 teaspoon water

2 tablespoons melted butter

Stalk trimmings from the rhubarb

5 tablespoons water

3 tablespoons caster sugar

Take the butter, still in its wrapping paper, and put it in the freezer for 20 minutes to harden.

Sift the flour into a bowl with the icing sugar. Add the salt. Remove the butter from the freezer. Unwrap about 2/3 of the block and, holding the end of the block in the paper, coarsely grate it onto the flour. To avoid grating your fingertips you may need to cut the very last of it into small pieces.

Using a sharp knife and rapid slicing and lifting movements cut the flour and butter together until the mixture resembles coarse gravel. The butter should be visible in a variety of different sizes, but few should be bigger than a pea.

Continuing to work as quickly as possible, sprinkle the iced water over the mixture 2 tablespoons at a time. Each time use the knife to mix the water into the flour and butter. When you have added all of the water the mixture should just start coming together, but there will still be dry flour visible. Use your fingertips to see it it feels like it will come together. If it seems too dry add another tablespoon or two of water – but no more – and mix through again. Then very quickly, using your fingers and not the palms of your hands, bring the dough together into a ball. Do not knead it or overhandle it. The dough should feel cold.

Lightly dust a piece of greaseproof paper about 40cm square with flour and place the dough onto it. Gently and quickly flatten the dough with the palm of your hand into a rough circle. Take a floured rolling pin and, using light, rapid movements, roll the dough out into a circle about 35cm in diameter, rotating the greaseproof paper in quarter turns after each pass. Reflour the rolling pin if it starts to stick. The pastry will be very short, so don’t worry about the edges cracking. Lift the greaseproof paper and dough onto a heavy baking sheet and put in the fridge for 20 minutes to chill.

Set the oven to 200°C (400°F, gas mark 6).

Cut the rhubarb into pieces about 8cm long. Put into a non-reactive (glass or ceramic) bowl. Sprinkle over the caster sugar and vanilla essence and toss together briefly. Leave to stand while the dough is chilling.

Remove the baking sheet from the fridge. Working quickly again, sprinkle the ground almond evenly over the pastry leaving a 5cm border. Arrange the rhubarb on top of the almond. You should have enough rhubarb for two layers. The first can be arranged somewhat haphazardly, and should use up any larger pieces. You may need to cut these in half lengthways to ensure they cook evenly. Retain the smaller stems for the top layer and arrange them more pleasingly.

Then, working around the circle, gently lift the edge of the pastry up over the rhubarb, folding, pleating and gathering as you go. Pinch it together quickly if any tears appear, since you want to keep the juices in as far as possible. Don’t worry too much about appearances though. You want to ensure that the pastry holds the rhubarb in place, but it is more important to get the chilled pastry into the oven quickly than for it to look primped and perfect.

In a small bowl put the aniseed or caraway seed, icing sugar and water. Stir until the sugar has dissolved. Add the melted butter and stir to combine. Brush this mixture generously over the pastry.

Put the tart straight into the oven and cook for about 40 minutes until the pastry is golden brown and the rhubarb bubbling.

While the tart is cooking put the rhubarb trimmings, water and sugar into a small pan. Bring to the boil, then simmer until the rhubarb has disintegrated and the liquid is syrupy. Strain the liquid off and, when the tart is cooked, gently brush this syrup over the rhubarb.

Serve warm with single cream.

Serves 8

Recipe and photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 23 March 2019

It took us the best part of a month to strip last year’s skeletons from the garden and to ready the planting for spring. It was good to take the time to acclimatise the eye and to look with care at what had been happening over the past year at ground level. Monkishly bald centres in a couple of the cirsium revealed that they need splitting to retain their vigour. Now that they have shown themselves again after winter dormancy, the advance of the Eurybia x herveyii will either need to be kerbed or, if I am brave enough, allowed to mingle and test both the tolerance of their neighbours and my courage to let the garden evolve as it wants to.

The feeling of openness is a shock at first, when all you have to counterpoint it is the flush of mid-February snowdrops, but by March I am happy to have the clean start. That said, I am keen to fill the gaps and for the ground to already be offering interest. Textures of evergreen epimedium and melica that have been happy in the shadows and the interest of new signs of life. Molly-the-witch and other early peonies, almost as good in the push of new shoots as they are in flower. The shine and lustre of Ranunculus ficaria ‘Brazen Hussy’. These early-to-rise participants are key. Not only do they engage you, like a flare that catches the attention, but they are invaluable for the early bees too, which on the still days are already working the catkins on the willows in February.

This is the second spring in the new planting and already I can see that I am wanting more lungwort. Pulmonaria rubra, one of the easiest and a present from a neighbour who isn’t a gardener but can rely upon it for needing little attention, was planted deliberately close to the verandah of the studio. This faces the morning sun and I leave the doors open as soon as there is a day warm enough to work at my desk with a connection to the outside. The sound of the first bumble bees working February flower is amplified in the trumpet-shaped blooms in an orchestra of activity that reminds me that I have a responsibility for the garden to offer as much early forage as possible.

Pulmonaria rubra is a modest plant, with plain apple green foliage and soft coral red flowers that fade pleasantly, like well-washed fabric, as they age. With me it is up and in flower in December and completely evergreen and so reliably weed suppressing. Where most pulmonarias by nature are edge of woodland or damp pasture plants, on our heavy ground this is an easy lungwort and quite happy here out in the open. Retentive soil or a cool position is their favoured habitat and one that makes them very useful amongst summer plants that rise above or overshadow them later in the year.

At the Beth Chatto Symposium last August, I was interested to hear how committed Cassian Schmidt was to using early ground covering plants at Hermannshof to protect the soil and suppress weeds early in the season, as well as providing early flower interest. He had introduced a layer of Primula vulgaris and early bulbs so that the ground was always covered and occupied between later-appearing perennials. As time goes on I will introduce more bulbs, but the likes of the lungworts, alongside violets and primulas, will be ideal in helping to provide this layer with the aim to combine plants that are happy in each other’s company, not fighting or competing, much as they would do naturally on the forest floor.

Where the shrubby Salix gracilistyla blur the garden’s boundary with the field, I have been busily planting Pulmonaria ‘Blue Ensign’. This time last year we painstakingly removed the Galium odoratum that in just a season had run riot there on our hearty ground, threatening to engulf every perennial in its path. We threw the mats of bedstraw down under the crack willow on the ditch, where it has now found its place and is behaving much better with other native plants that are up for the competition. I left the area fallow during the summer to ensure I hadn’t missed a bedstraw tendril but, as autumn opened up the area again, I have replaced it with Pulmonaria ‘Blue Ensign’. This highly floriferous lungwort has an electric, gentian-blue flower, that first appears in February and continues to build in volume through March into early April. It also has a simple green leaf, coppery at first, smaller and fleshier than P. rubra. The plants are clump-forming and will survive for many years without splitting. New plants are put in at around a foot spacing and I expect them to touch and do their job of protecting the soil by autumn.

Though I initially introduced the lungworts here at Hillside with two that have plain, green foliage, a more typical characteristic is the mottled leaf which appears in some as a dappling of light-reflecting pearly spots, in others a more dramatic complete silvering. The Latin name is derived from pulmo, meaning lung, as the spotted leaf was thought to resemble an ulcerated lung and in early apothecary gardens it was used as a treatment accordingly. Silver plants are usually adapted to refract light in bright sunny conditions, but the silver-leaved pulmonarias are a welcome element to brighten the shadowy places.

The Pulmonaria officinalis selections and hybrids typically have the dappled leaf and offer a wide choice of colours ranging from white to pale blue to cobalt with ‘Sissinghurst White’, ‘Cotton Cool’ and ‘Highdown’ among commonly available varieties. Lungworts are promiscuous so you will soon find seedlings that show variation if you are growing several together, but it is worth seeking out the ones that fit the way you want a planting to feel. Pulmonaria saccharata is the most dramatic of the group, with forms showing much variability, but the silvered and spotted foliage is characteristic. I grew the straight species when I was a boy, having seen them used at Chelsea by Beth Chatto. They thrived in a cool position on our thin, acidic sand and proved their worth in illuminating a garden that needed sparkle once the trees provided shade.

Pulmonaria saccharata ‘Leopard’ (main image) is one of my all-time favourites. Again, early to start in February with flowers that age from soft brick red to dusky old rose. There is a lightness in the variation. ‘Leopard’ is a robust plant, easily reaching a foot and a half across and, as the flowers pass as spring gives way to summer, the heavily spotted foliage expands to become the focal point. I first grew it under leafy Tetrapanax papyrifer ‘Rex’ in our Peckham garden and found it prone to mildew in dry summers there, but moisture or a good mulch at the root will diminish this likelihood. Here on our hillside it is pooled under the mulberry where, as the heavy shade gathers, it keeps the darkness interesting. I hope that the erythronium that I’ve laced amongst it will favour me and not find our open hillside intimidating, and that the lungworts will help keep the microclimate more stable for them.

I’m using the silvered varieties carefully here for fear that their eye-catching foliage might prove too ornamental for the feel of the planting, but as a glint of light Pulmonaria ‘Diana Clare’ – which must have some saccharata in her blood – is a treasure as a complement to darker foliage. The flowers are dark plum taking on a violet cast as they age and are tightly clustered as the plant awakens from dormancy. I have them amongst Eurybia divaricata, which overshadows them later in the autumn, but provides a nice scale change. The lungwort with a simple elongated silver-green leaf, the aster fine, lacy and bottle green, ensuring that one end of the season works very nicely with the other so that the garden goes not in fits and starts, but flows between seasons.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 16 March 2019

Wind-whipped, grey velvet

shoals caught in burnished nets of

silver and bronze

Published 9 March 2019

Words: Huw Morgan & Dan Pearson / Photograph: Huw Morgan

Stripping away the last season’s skeletons comes with mixed feelings and I judge the moment carefully. There has been joy in the leftovers and I have savoured the falling away, with each week revealing a new level of transparency, but no less complexity. Light arrested where it would have fallen without charge or definition if we had cut the garden earlier and the feeling that we are more in tune for standing back and going with the winter.

It has all been worth the wait, but by mid-February, when the snowdrops were drifting in the lane, the need to move became clear. The tiny constellations of spent aster were suddenly joined by the willow catkins on the Salix gracilistyla that nestle by the gate. Grey buds like moleskin, soft, glistening and alive with bees. The old growth alongside them was made immediately apparent and the need to embrace the change an easy step to make.

This spring, after completing the planting the autumn before last, we have twice as much garden to clear. This time last year two working days with three pairs of hands saw the skeletons razed and taken back to base. With more to wade through this year four of us made a day of it the first weekend to break into the oldest parts where the perennials have now had two summers of growth. The weather had been dry and the soil was good to walk on without feeling like you were straying from the path. The sun came out to fool us into thinking it was April and, sure enough, at the base of the remains there were clear and definite signs of life. Buds red and rudely breaking earth already on the peonies and emerald spears of new foliage marking the hemerocallis.

I worked ahead of the team, stepping into the planting where I’d spent the winter analysing the plants that needed changing or adjusting. Last year it was to remove all the Lythrum salicaria ‘Swirl’, which were replaced by Lythrum virgatum ‘Dropmore Purple’, a form that feels closer to the wild loostrife. This year, I have lifted a stand of Panicum virgatum ‘Rehbraun’ by the lower path that were shielding the planting below them. They have done better than I had thought, so half were tied in a topknot to make them easier to move and then staggered through the beds where I need this accent and volume for late summer and then winter. I left them standing to check how they marched and jumped through the planting to bring it together. Now is the time to move grasses, for they engage fully with dormancy early in autumn and with life in root activity in early spring. Being late season grasses, I have placed the panicum where they will not be overshadowed too early by their neighbours. The two year old plants were a handful to heave, but with a sturdy root ball they will not look back. With spring now on our side, the timing should be perfect.

I have not planted bulbs yet, or not as many as I am ultimately planning for once I have more maturity in the planting. I will keep them in groups under the trees and shrubs where their early season presence can be allowed for. Planted too extensively amongst the perennials and I would have to cut the garden back sooner, at least two weeks earlier, so as to not trample their emerging shoots. As the willow catkins are my litmus, I will let them determine the date that the skeletons are cleared and not be driven by the march of bulbs. That said, there will be exceptions. I have a tray of potted Camassia leichtlinii ssp. suksdorfii ‘Electra’ that were impossible to plant in the autumn when the garden was still standing. They will find a home where I have lost deschampsia to voles. This is the second year running that their homes have undermined this layer in the planting and it feels more appropriate to bend and change direction.

The new start with a clean palette reveals a gap in this new garden. One that, with time to get to know the new planting, I can now plan for. Early pulmonarias are already bridging the space beween the winter skeletons and the real beginning of spring. I have planned for more P. ‘Blue Ensign’ so that it’s gentian blue flowers can hover under the willows. Shade tolerant ephemerals such as Cardamine quinquefolia and Anemone nemorosa will also be useful to weave amongst later clumping perennials that can take a little well-behaved company in the spring whilst they are still just awakening. The layering will be important as I get to know more and, in turn, become more demanding.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 2 March 2019

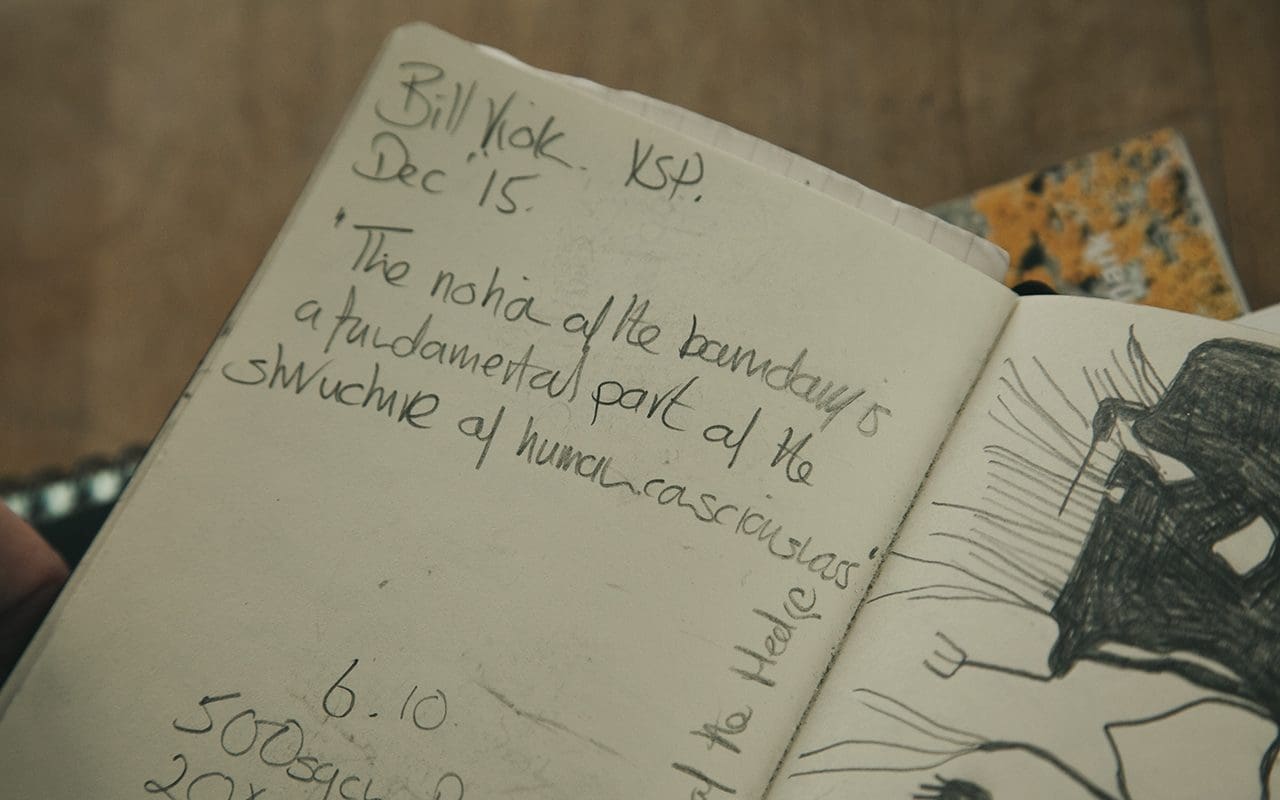

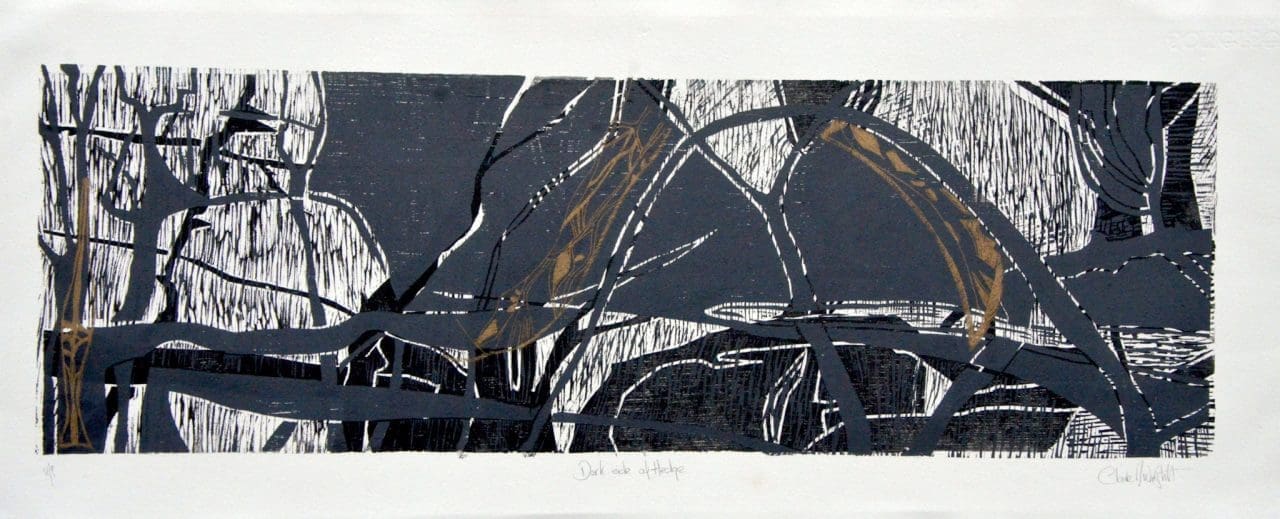

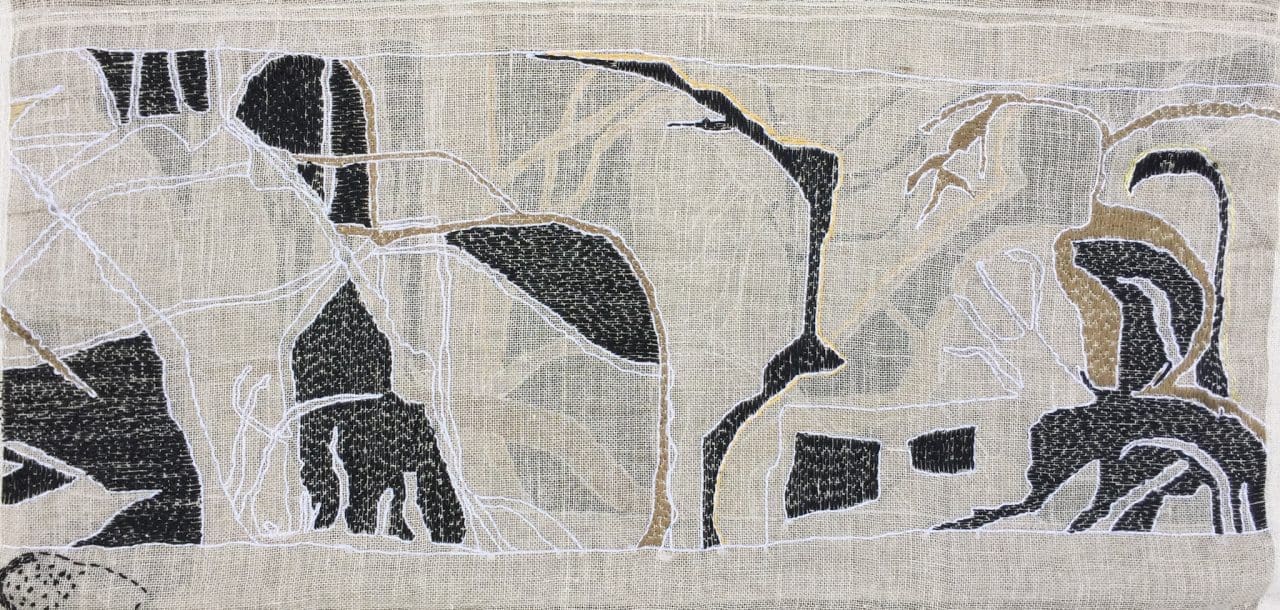

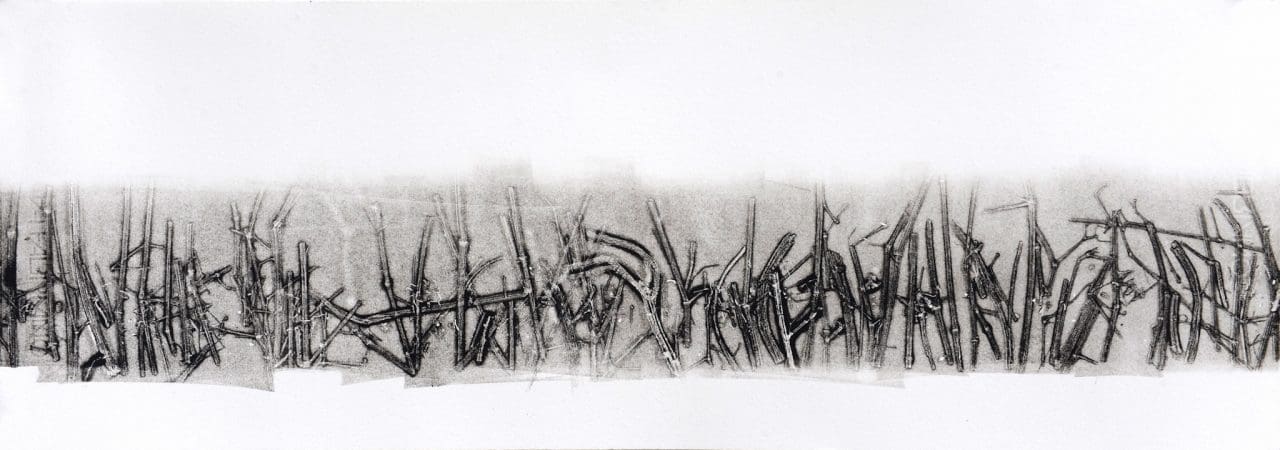

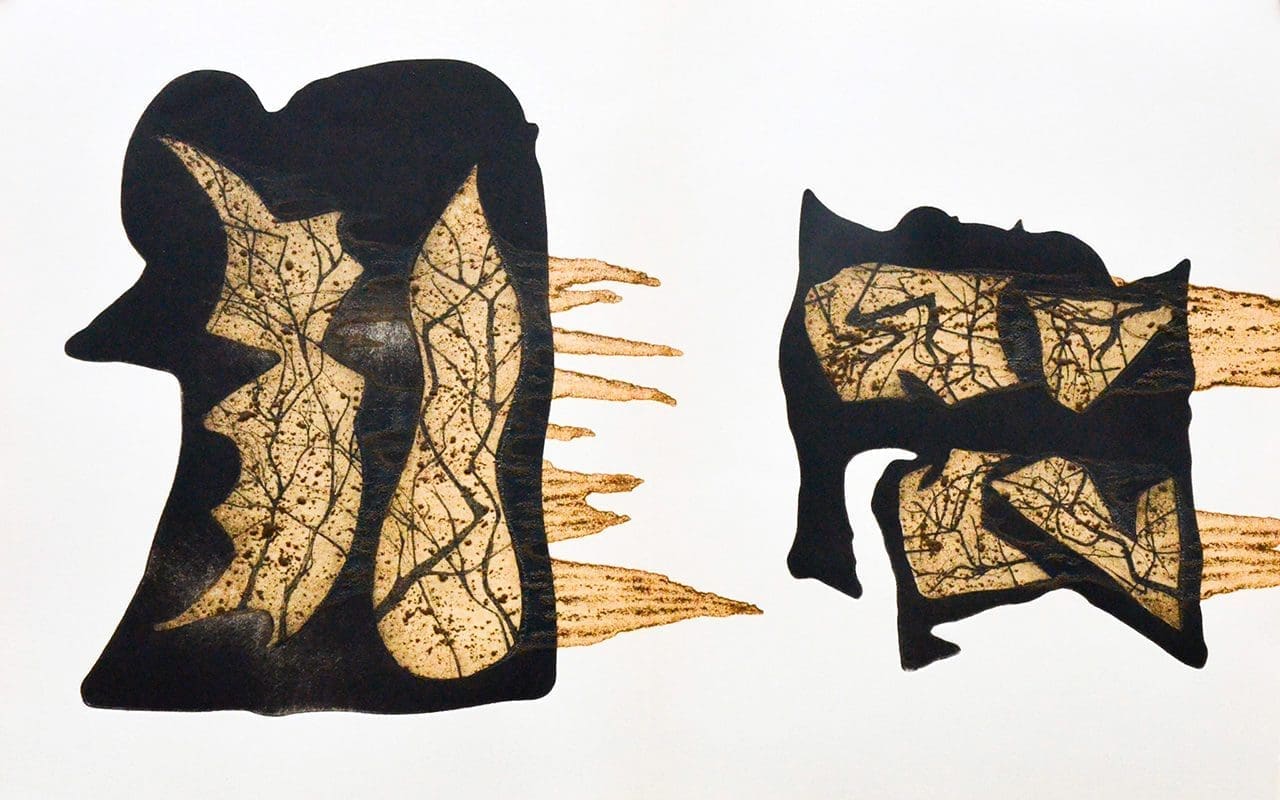

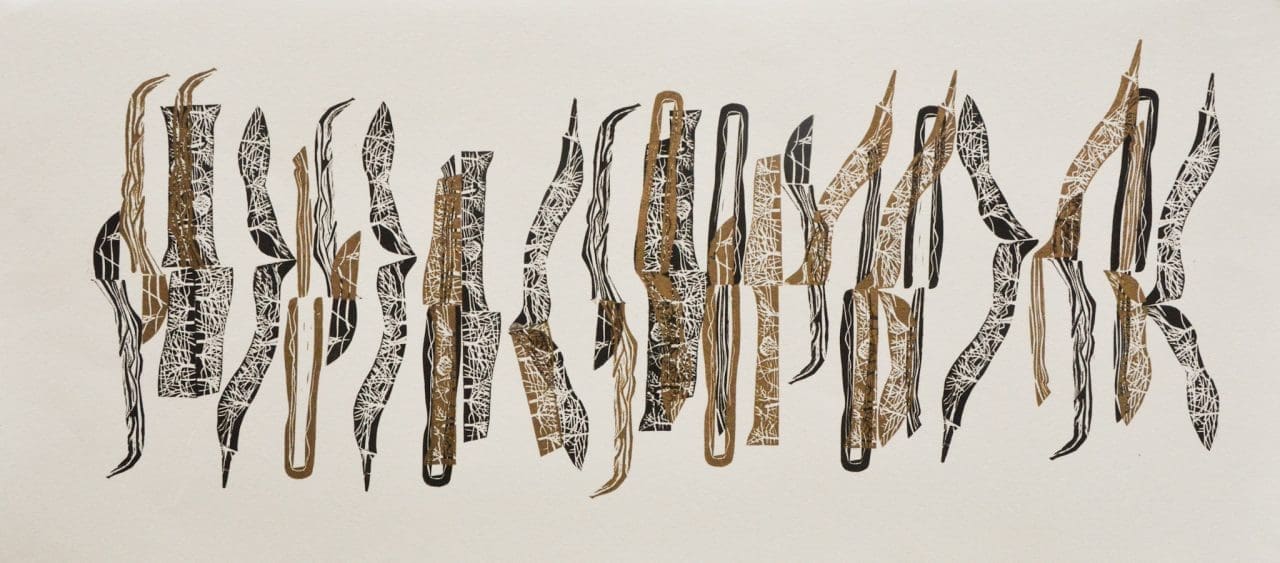

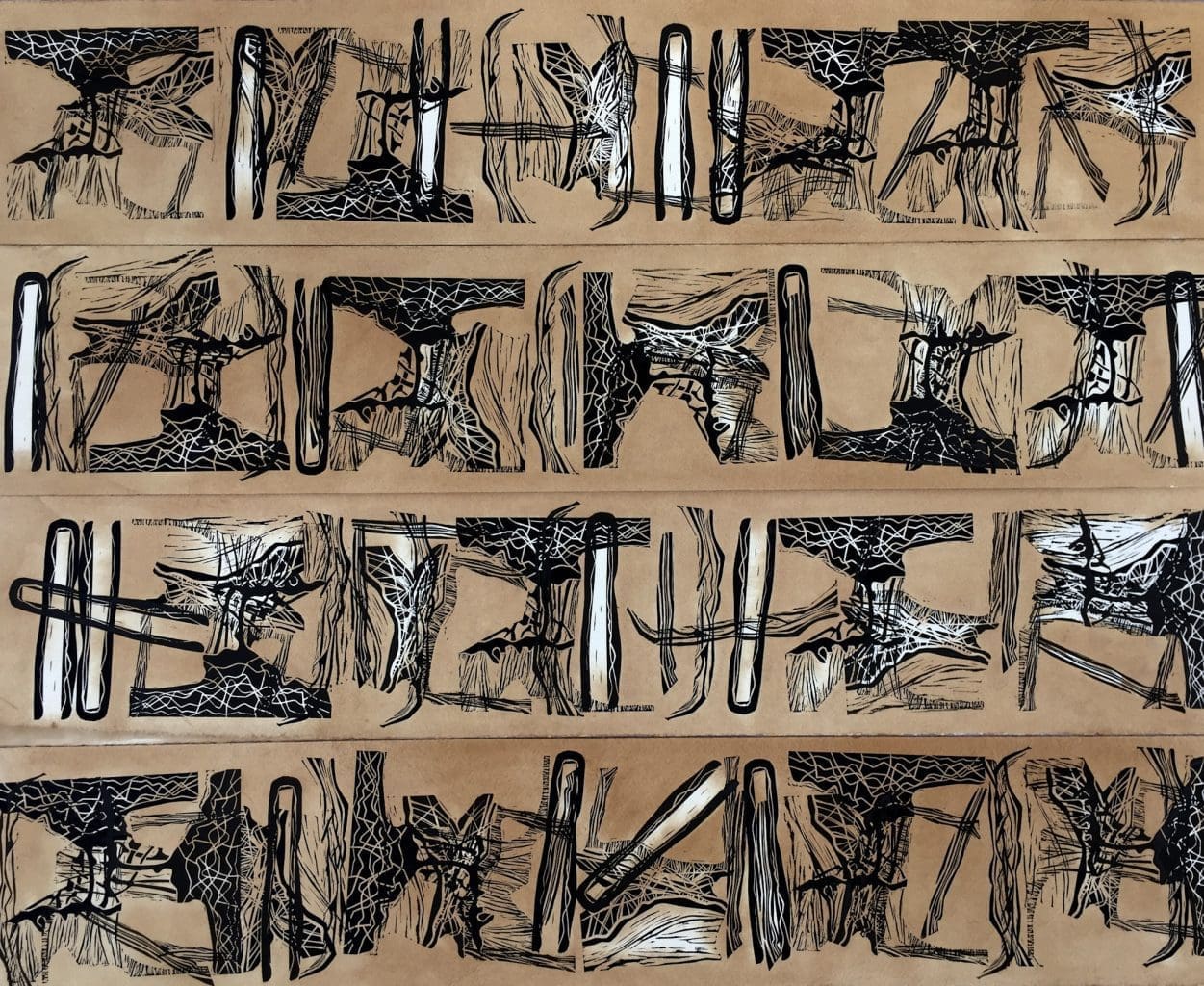

Claire Morris-Wright is an artist and printmaker working with lino and wood cut, etching, lithography, aquatint, embroidery, textile and other media. Last year she had a major show, The Hedge Project, which was the culmination of two years’ work, and which used a hedge near her home as the locus for examining a range of deeply felt, personal emotions.

So, Claire, why did you want to become an artist?

I’ve just always made things. As a kid I was always making things. So I’ve always been a maker, creative, and I was always encouraged in that. My parents used to take me and my brothers to art galleries and museums when I was young and I loved it.

As a child I was always drawing, making clothes for dolls, building dens with my brothers and creating little spaces. I was not particularly academic, but a good-at-making-clothes sort of girl. I always knew I wanted to go to art college, so that was what I aimed for.

My secondary school, Bishop Bright Grammar, was very progressive, where you designed your own timetable and all the teachers were really young and hippie – this was in the ‘70s – and we could do any subject we wanted; design, textiles, printmaking, ceramics. So I took ceramics O Level a year early with help from the Open University programmes that I watched in my spare time.

Then I went to Brighton Art College and studied Wood, Metal, Ceramics and Plastics, specialising in ceramics and wood. Ceramics is my second love. I have a particular affinity with natural materials, the earthbound or anything connected to nature. That’s what moves me. My work has always been about land and landscape and what’s around me and how I navigate that emotionally.

In terms of how I work, I simply respond to things. I respond to natural environments on an intuitive and emotional level. I try to explore this through my practice and understand why I had that response and aim to imbue my work with that essence. My artistic process is completely rooted in the environment that I live in. Like Howard Hodgkin said, ‘There has to be some emotional content in it. There has to be a resonance about you and that place.’

How do you work?

I go to the Leicester Print Workshop to do the printmaking. It’s a fantastic workshop facility. I was involved in setting that up, a long time ago now. When I first moved to Leicester in 1980 I was part of a group of artists who set up a studio group called the Knighton Lane Studios. We wanted somewhere to print and so set up our own workshop, which was in a little terraced house to start with. It’s moved twice to its now existing space in a big purpose-built building. It’s all grown up now, which is great. However, I rely mostly on my table at home or the outdoors to make work. I don’t have a studio, but I believe that since I am the place where the creative thinking happens I can make and create wherever I can in my home.

Are you still involved in managing the printworks?

I stepped out of it before its first move, because I was working full-time in Nottingham at the Castle Museum, where I was the Visual Arts Education and Outreach Officer, developing interpretive work from the collection and contemporary exhibitions. I was responsible for getting school groups and community groups in to look at the art collections. We then had two children, so it was only when they were older that I had more time and returned to my practice and the print workshop.

So tell me about how the Hedge Project came about?

I had a few experiences that were deeply shocking and subsequently had a period of depression. During that time the hedge became very important psychologically and I found that I needed to go up to the hedge on a regular basis. I started to develop a relationship with the hedge knowing there was this pull to record these emotions creatively. I produced a large body of art work with Arts Council funding and sponsorship from the Oppenheim-John Downes Memorial Trust and Goldmark Art. I held three exhibitions of the art work, made films and have delivered community engagement workshops over the past six months.

What was the feeling that drew you up there?

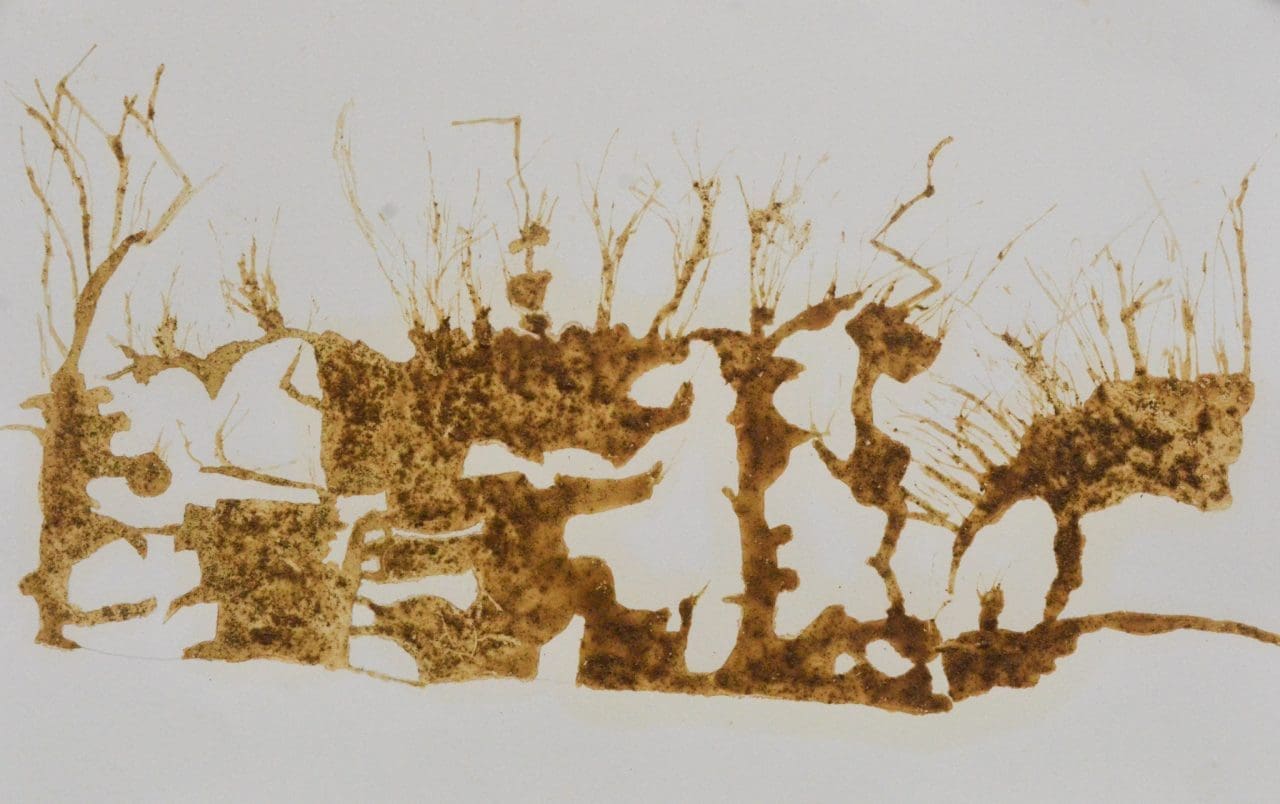

It was definitely quite powerful how I felt drawn to it. It was a beautiful structure in the landscape that was seasonally changing and I was changing at the same time. It is very prominent on the horizon and, because I walk around the village regularly, I just kept seeing it, so I started walking the length of it, looking at it, drawing and thinking about it. I did that every week for two years. Gradually my relationship with the hedge became deeper and started to take on more significance as a symbol. The metaphors it conjured were highly pertinent. Through this introspection I became interested in ideas like barriers, confinement, boundaries, horizons, chaos, liminal spaces and structure. The whole project was a personal and creative exploration of the place this hedge conjured up within me.

So how did you start work?

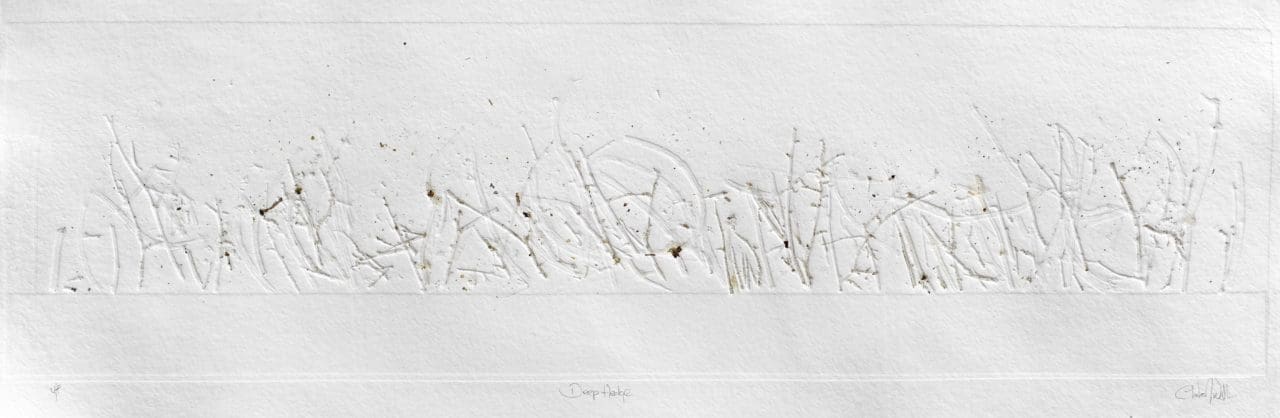

After observing, recording and drawing for some I firstly made a one-off drypoint etching. I started by doing a drawing on a big aluminium plate, which I scratched into with a drypoint needle. I was just doing it on the sofa in the front room, scratching away at it in the evenings. Then, when I went into the print workshop to print the plate, I couldn’t believe how angry it looked. My immediate reaction was, ‘I’m going to leave that. I’m not going to do anything with that at all.’ They were quite visceral, those first emotions, they were really powerful. A hedge is a barrier, and I had put up some emotional barriers for the best part of 35 years. So that first piece is about the anger and the spikiness of the hedge, and the complete and utter chaos in the hedge, but also that it seems very organised. Although confronting, I was really interested in and excited by the range of emotions coming straight out of me and into the artwork.

I’m interested in you creating your work at home, on the sofa, at the kitchen table. How does that affect your work?

I really wish I had a studio, but I don’t. The idea when we bought this house was to convert an outbuilding into a studio, but it got full up with racing bikes and skateboards and boys’ stuff. When the boys get their own homes, I’ll have some more space.

As a woman there is something interesting about not having a studio and being forced to create my work in a domestic environment. I think there are quite interesting politics around that. Not all women have studios or can afford to, and they are forced to use the kitchen table. It does make me go out and draw quite a lot as well, which I like. I also like the idea of a community of artists, because we are quite isolated here. I enjoy going into Leicester and seeing other artists and talking to them and having that interchange as well. That’s really important to me, having relationships with other artists, especially women artists. During the Hedge Project I wanted to meet with other women artists more often, so I set up a women artists’ support and networking group that would enable us to support each other around our work, to offer constructive support to each other. We started to meet last year.

How did the work develop? Did you continue making more etchings?

No. I do lots of work on different pieces at the same time and in different media. I usually try and keep 2 or 3 plates spinning. I do textile work as well, so I try and keep a textile piece on the go and embroidery. So that is something else that I can do at home in the evenings, if I’m not creating printing plates.

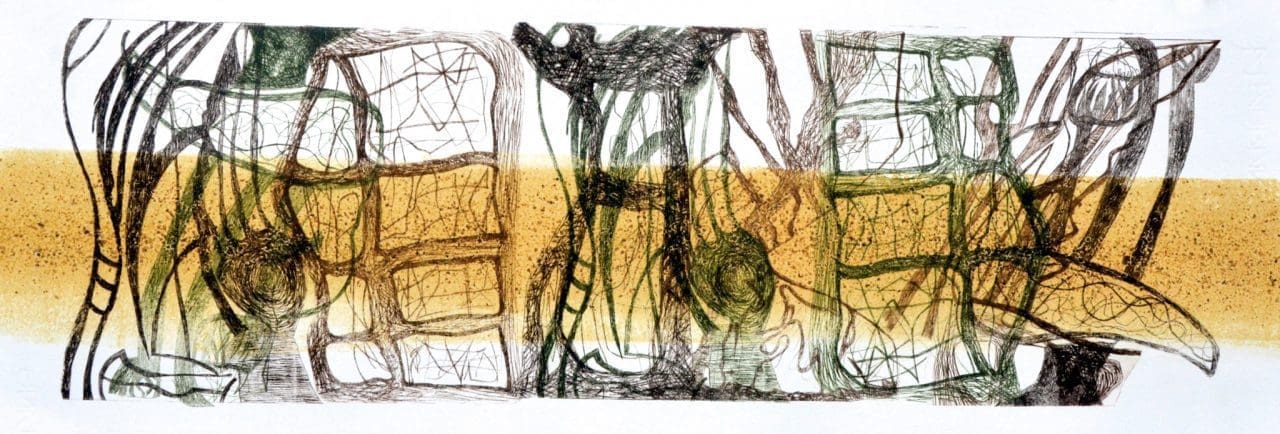

I applied for some mentoring from the Beacon Art Project in north Lincolnshire and successfully got onto that. For that you got two day long mentoring meetings. My mentor, John, came and had look at the work and said, ‘It’s all very good, but it all looks very much the same. You need to focus on something. What is it you’re thinking about at the moment? What’s the most recent piece of work?’. I told him I’d been doing this work on some hedges around here, and he encouraged me to look at a hedge. So that’s how I came to focus on one hedge and that was a hedge that I was looking at closely because of its geography, its placement. It’s in a really beautiful place on the horizon and it was easily accessible. I particularly liked the way that the light shone through it so you could see the structure and the pattern, the beautiful lines. Also the understory of plants that were growing through it, as well as the structure of the hedge itself. So the work is also about the ‘music’ that’s growing through it.

John then asked me where I wanted to go next with the work, and I said that I’d really like to get funding. I’ve spent all my life supporting other artists through museums and galleries and working with other artists, but I’ve never done it enough myself and at that point I needed to do something for myself. I started to go to galleries and places where I already had a relationship, where I knew the people that I could go to and say, ‘This is my story. Are you interested in this as a proposal, as a project with community engagement and artist-led days?’ Eventually I managed to get Nottingham University, Leicester Print Workshop and Kettering Museum and Art Gallery as my thread of spaces. I wanted the exhibition itself to be like a little hedge running through the Midlands.

I was delighted to get the exhibition space at Kettering, since it is the nearest to the actual hedge. They also have a relationship with the CE Academy, which is for students that have been excluded from school. So with each venue I worked with the educational outreach officer and looked at groups that they weren’t reaching, young people or adults with mental health issues. Because of my experience I wanted to give back somehow, because we all hit borders, barriers and edges in our lives, and we need support and perhaps creativity can be a way of understanding that.

I also spent a day at each venue gathering hedge stories. I asked people if they had a story about a hedge. First of all I think they wondered what I was on! Then, as I engaged them a bit more, people told me some fantastic stories. One guy told me about how trees were interspersed in hedges to stop witches from flying over them. I’d never heard that story before. Two other men I spoke to were railway workers, who told me that they used to grow fruit trees in the hedges along the railway lines, hiding them there, and they would harvest plums, apples, cherries. I thought that was such a lovely story, the idea of these men cultivating the railway network. I heard lots of these wonderful stories, and that was when the Woodland Trust got interested. They were excited by the fact that I’d got 36 accounts of people’s relationships with hedges and told me that it was a substantial record of narrative local history. So we’re talking at the moment about doing something with those stories and I’m hoping that will be the beginning of an ongoing relationship with the Woodland Trust.

Because of my personal politics I can’t just throw art on the wall and then walk away. I have to have a relationship with the people that are coming in to see it. I want to be able to say, ‘This is my thinking. I’m not some special person. I’m just a normal person like you. This is how I see the world. This is how I interpret what I see and experience. This is my way of looking at things.’ I really enjoy doing that. The sharing.

What sort of effect did the workshops have on the kids that you were working with?

They were amazing. They all came in with their shoulders hunched, not making eye contact, with a what-are-we-doing-here look on their faces. They wouldn’t do anything at all for the first half hour, but in the end they all produced amazing work. I brought a big bag of stuff from the hedge itself, clippings and twigs and leaves and weeds and things and showed them how to print directly from nature, and then to cut things up and do different things with them, playing with different processes and techniques. I was getting them to see how you can use nature creatively to communicate ideas about yourself and your experiences.

You use a range of different media. How did that exploration come about and what did each medium add to your experience of creating that body of work?

So it starts with a sense or a notion of something and then I do drawings and play around with shapes and forms, all because I want to get across a particular feeling about something.

Some pieces came about specifically because of the lichens in the hedge. I wanted to make some ink from them so I scraped some of it off and mixed it with some oil and Vaseline and rollered this lichen ‘ink’ onto a piece of paper. I felt that I needed to overlay some forms of the hedge onto that, so I scratched into these little plastic plates – this time with a scalpel, as I wanted really fine lines – and each colour is a different plate. I repeat and use the same plates in different pieces in different ways. Sometimes they will be very ordered, other times more chaotic.

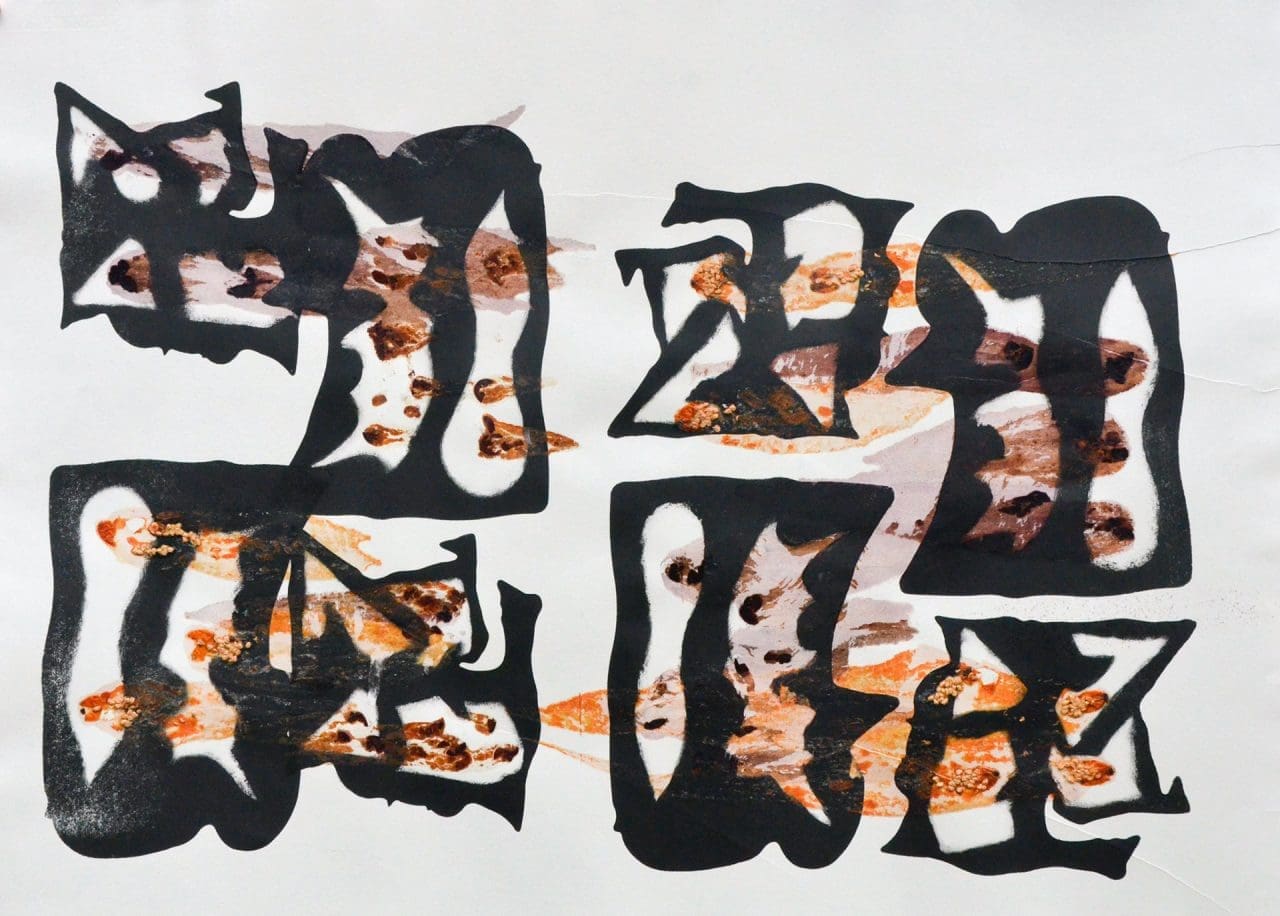

I also made some lino plates and then overprinted them. I did it just as practice, wondering what those shapes that I’d drawn, classic hedge shapes, would look like. The hedge was cut at the top and some I turned upside down and arranged vertically. I was just playing around, but when I looked back at this one strip I’d done I thought they looked a bit like hieroglyphics. I was also thinking about the counselling I’d been through and the idea of tea and sympathy and so I stained the paper with tea, which is something you do to make paper look old. I was enjoying putting all these different things together and then people started saying how it looked like music or some sort of language. And I thought about the sort of language that my therapist used, which was really interesting to me. I liked the way that she used particular words. So I started to develop this hedge language. There was also something about the hedge standing up for itself. Because I am the hedge.

What was your emotional process with each of these different techniques. Did it bring up something different for you each time?

I don’t produce editions of things. They’re all one-offs. Once I’ve said what I want to with a piece, I’m not interested in repeating it. So I like the single process. I like the high failure rate inherent in this too, because sometimes valuable things come out of what you initially think is a mistake.

It was a visual, creative and emotional journey going through the seasons and each season threw up something different for me. I was very disciplined about thinking, ‘What is it you’re doing? Why is it you’re looking at that? Is it the structured branches or the things growing through them? Is it the fruits or the lichens or the soil?’. So I investigated all of it. I made rubbings, drawings, textiles, embroidery, dresses. I just wanted to do all of it and make lots of work exploring everything I was feeling. It’s an intuitive and organic process though. I don’t go in with a preconceived approach or necessarily an idea of which medium I will use.

Tell me about the dresses.

I wanted a bit of me in the hedge. I wanted to put a bit of me in there. So I made four dresses and one of them I left out in the hedge for a year, where it accrued all the dirt and detritus of the hedge throughout the seasons.

And then I worked with the lichen in the hedge, which became quite interesting to me because I discovered that they thrive in toxic environments as well as clean air. I contacted a local lichen expert and he came over and catalogued the lichens in the hedge for me, and he told me that lichens aren’t always a signifier of clean air, which is what I had always thought. Sometimes they grow because of particular toxins in the air, even petrol and diesel fumes. So the bright yellow lichens are reacting to toxins in the air, sulphur apparently.

So I did a big 12 foot long wall piece about lichen with this puff binder, which has a three dimensional quality like lichen, and I also made a dress using the same technique as well as flocking. That was the first time I had ever worked with screenprinting, which I’d always found it a bit flat previously.

I wanted to ask you about the mapping project too.

That’s an older piece of work also looking at issues around family relationships. Some of the same things as became apparent to me in the Hedge Project, but I wasn’t conscious of them then.

I had been invited to show some work in Leicester that was based at the depot which was an old bus station. We had to come up with work that was linked to the depot and the immediate area in some way. I remembered my dad cleaning the oil from the car dipstick with his handkerchief when I was a child, and I thought that bus drivers in the ‘30s and ‘40s must have had hankies in their pockets for just the same reason.

And I love hankies, anyway. I love proper fabric handkerchiefs. So I looked at some of the very oldest maps of Leicester at the library there and did some drawings of them and then printed them onto cotton handkerchiefs. To display them I made a gold paper lined box with a cellophane window, just like the ones my aunty would give me as a girl at Christmas.

I also hand-stitched secret messages onto them which, as on a map, were like a key. Things like ‘rough pasture’, ‘rocky ground’ and ‘motorway’, and used some of those phrases as metaphors to describe how I was feeling.

I also made a series of map works about being stuck at home; cloths and floor cloths, which I stitched landscapes onto. And I made some hankies that are about the forest behind our house, from aerial maps of the forest. Sometimes when I’m out walking I find people that are lost and a few times we’ve had people appear in the village who think they’re somewhere else, so I’ve had to give them a lift back to the car park on the other side of the forest. I felt like I wanted to be able to give these people something. Something that I could easily get out of my pocket, to be able to say, ‘Here you are. Here’s a map, so you won’t get lost again.’

What are you working on now?

I am currently doing an evaluation for the Arts Council and embarking on a body of new work based on natural lines, cracks and gaps in the landscape. We have Rockingham Forest behind our cottage, which is on the site of an old Second World War army airfield, RAF Spanhoe. So I’m in the woods currently, with an old map from the ’40s that my neighbour gave me, looking at the way nature is reclaiming the cracks and small spaces in the old concrete paths. The deteriorating concrete has broken up into really beautiful shapes, softened by moss and other vegetation. In the spring the cracks are full of tiny primrose seedlings. I love seeing nature saying, ‘It doesn’t matter what you lay on top of me, I’m still going to grow through it.’ I just really love that idea of nature taking over something ostensibly ugly, like concrete, and making it really beautiful.

Interview, artist and location photographs: Huw Morgan. All other photographs courtesy Claire Morris-Wright

Published 23 February 2019

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage