wishing you all a very happy christmas and a peaceful new year

see you in 2020

Kaori Tatebayashi is a Japanese ceramicist living and working in London. She comes from a family of ceramics traders, and was surrounded by traditional Japanese ceramics from an early age. After gaining an MA in Ceramics from Kyoto City University of Art, in 1995 she came to London on an exchange programme to study at the Royal College of Art. Kaori makes both sculpture and tableware, but it is her sculptural pieces, which are inspired by plants and nature, which I was interested to find out more about.

Kaori, you have a longstanding family relationship with ceramics. Can you tell me about this and how it influenced your development as a ceramicist ?

I was born in Arita in Japan, a little village renowned for Arita porcelain, which in Europe is known as Old Imari. My grandfather was an Arita-ware merchant and took orders from hotels and restaurants from all over Japan. The scene of my family gathering together to pack tableware commissioned from various potteries in the village in navy blue paper with our family company logo remain vividly in my memory as a fun event.

Each May, we participated in a pottery festival in Arita. My cousins and I were allowed to sell little porcelain figurines next to adults selling tableware and, when we sold the figurines, we were treated with too many ice creams by visiting relatives. In 2016 Arita celebrated 400 years of porcelain production. Although I don’t work in porcelain, ceramic is definitely in my blood.

You studied ceramics both in Japan and then in London. Can you tell me about the key things that you learnt in each place ?

In Japan, we were taught as if you were apprenticed to a master potter, learning everything from traditional spiral wedging, which they say will take 3 years to master, to throwing and hand-building techniques to firing electric, oil, gas and wood fired kilns. By the time you graduate from university, you have learnt everything you need to know to run your own ceramic workshop. It was about skill-based making at BA level then, for the MA, you focussed on how to express yourself in clay and with the range of ceramic material.

During my exchange at the Royal College of Art and a short residency in Denmark, I was liberated from all of the rules and restrictions and the traditional approaches towards clay and glazes I had blindly been studying in Japan and my work changed dramatically, especially the finish.

In order to make what I do now, I needed all the skills I gained from the training I had in my university years in Japan as well as the freeing of my mind which I got from studying in the U.K.

Why did you decide to stay in London to continue your ceramic practice after finishing your studies ? What did the city offer you that Kyoto didn’t ?

After my exchange at the RCA, I went back to Kyoto to finish my MA then lived in Tokyo for over 4 years mainly teaching, but I didn’t enjoy my life there. I missed being close to nature and couldn’t find my place in Tokyo which was too fast, too vast, and I felt the life there had no sense of the seasons. I moved back to the U.K. in 2001 and have stayed here ever since. People are surprised when I say London is full of green and that life here is much calmer than in Tokyo, but it’s true. I don’t feel the urge to be near nature in London as I did in Tokyo.

Also I choose to live and work in the U.K. because my sculptural work was better received here than in Japan, which was still very much stuck in tradition then.

You started making ceramic sculptures of inanimate objects, especially clothing. What was your impetus for making these pieces ?

Individual objects were my early pieces. At that stage, I was curious about how far I could push the material and challenge my skill. Also, my focus was on memory. The clay’s ability to capture time and its elusive existence, simultaneously having both fragility and permanence, overlapped with my ideas about memory. I was making old-fashioned, everyday objects which encouraged people’s memories and played with the sense of time being stopped.

I started making sculpture in my university days, and it was the reason I came to study at the RCA. Ceramic sculpture didn’t have a place in the world of traditional Japanese ceramics. Making tableware came after graduating with my MA, when I was teaching full time. My short periods of free time only allowed me to make small, repetitive pieces and so was most suitable for making tableware, which also came naturally to me due to my family background.

Can you explain the development of your work from the replicas of single items of clothing to the more formal tableau installations of multiple pieces which included a wide range of different subjects ?

My focus was on the challenge of replicating each item. In a way, I was training myself, developing my skills further. You could see them as my studies. Once I had mastered the required skills, I started to create still life series, much as you would do with drawings.

Where did your most recent and current interest in plants, flowers, fruits and vegetables (and insects and animals) originate and what is the link between these pieces and your earlier work ?

My passion for gardening started influencing my work gradually, but even in a much earlier stage of my life, my grandfather who collected and named some wild orchids from his local mountain, must have seeded something in me as well. My very first flower piece appeared in 2005, which I made for Ceramic Art London held at the RCA (it has now moved to Central St. Martin’s). It was a single rose stem, forgotten and dying in a vase. A moment preserved in ceramic, which later became my main theme. In the true sense, I am not trying to preserve plants, but time itself. By preserving plants, which have a very short life, you get the sense of time being captured and permanently frozen. I often add insects and other creatures, especially snails which, although they have movement, it is very slow, in order to enhance this sense of time being stopped.

Can you tell me about your working process ? How do you make your flower pieces ?

I usually work by going straight into modelling in stoneware clay, observing real flowers and plants from 360 degrees. I quickly calculate what method is most suitable to use, which part I should make first, the drying time and which is the best forming technique to use. I have been working in clay for nearly 30 years now. By looking at object, I can immediately tell if the object is at all possible to make and how to achieve the form.

The tools I use are very simple, my hands and a knife which I made myself. If it is a flower, I make it petal by petal, no secret or magic involved!

The pieces must be dried slowly, then fired straight to 1250°C without a bisque firing.

Can you tell me about the Banquet pieces and the work that you created for your exhibition at Forde Abbey ?

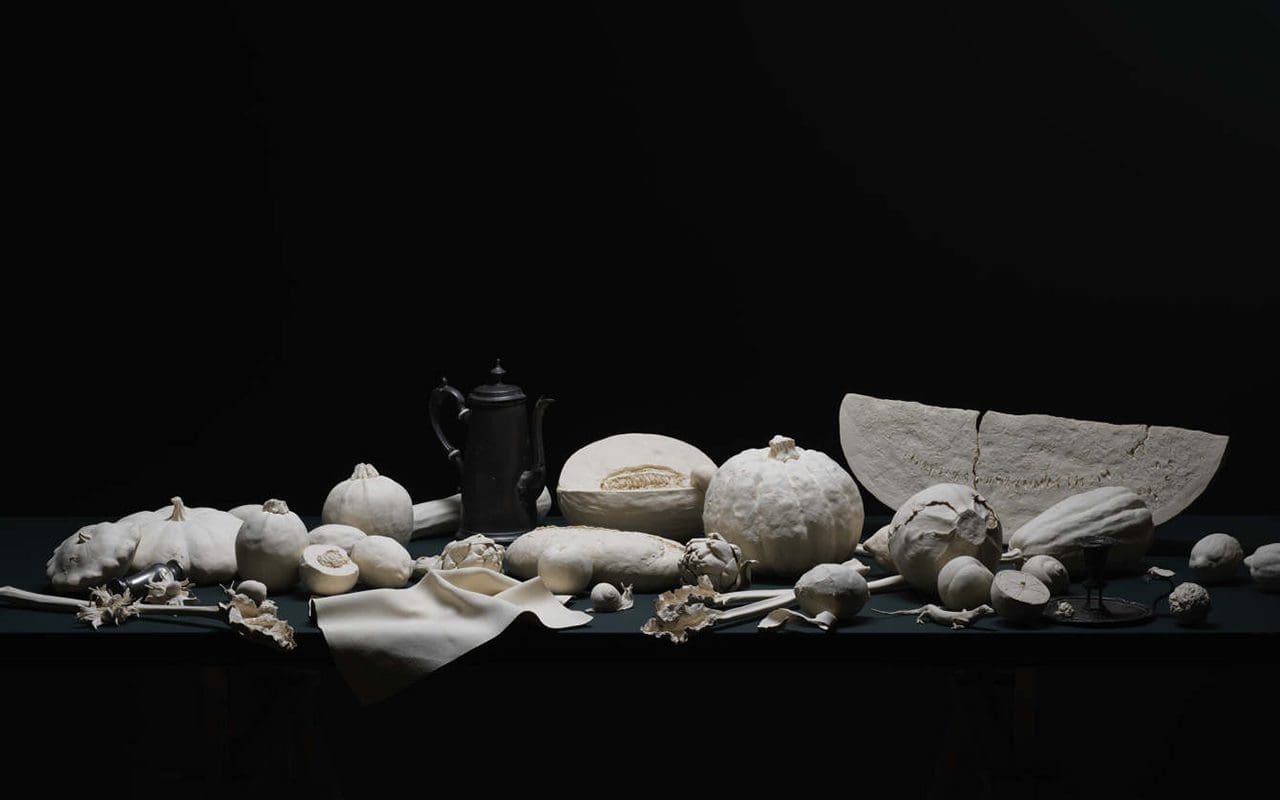

The Banquet is one of my largest installations. It was developed from my small still life series and I wanted to create a large flamboyant scenery based on the feel of the Dutch Old Master painting.

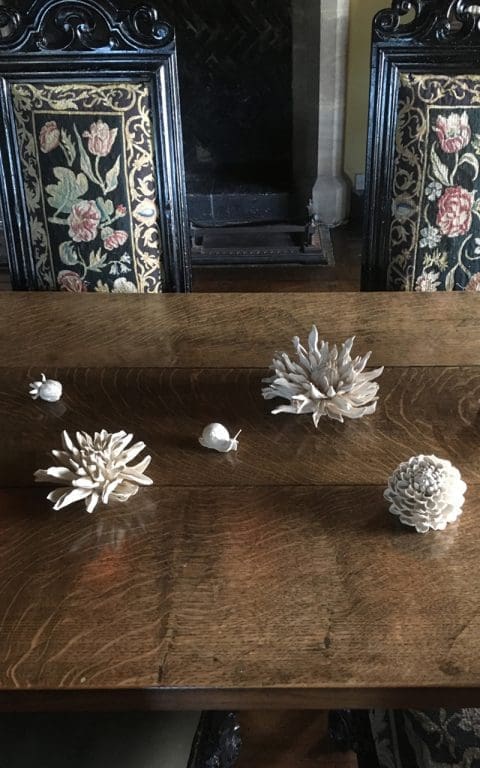

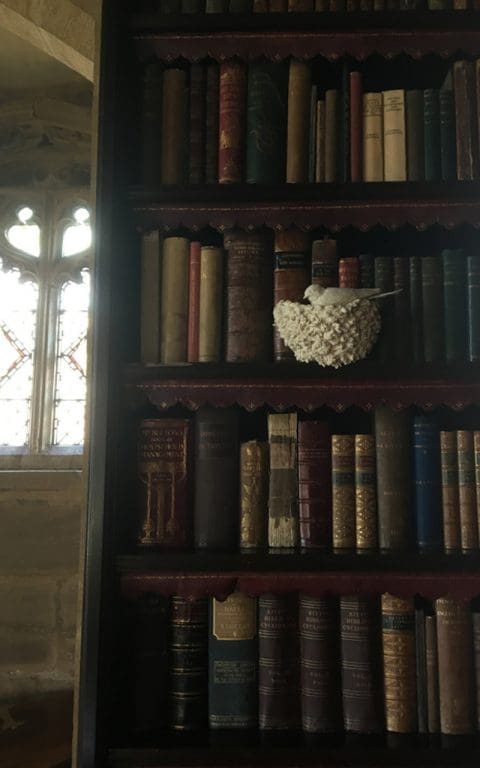

The work exhibited at Forde Abbey was my first site specific installation, which I created in my studio after a week’s residency there. To correspond to the feeling of the 900 year old library and the beautiful gardens and nature there, and because the exhibition was held in September, I created dahlias which I scattered down the central table, pumpkins (the originals of which had been grown in their kitchen garden) peeping from between the old books and swallows nesting in front of the book shelves. I wanted a fairy tale aspect and a slight spookiness, but not too conceptual so that visitors could really enjoy the experience.

What was the inspiration for the black stoneware pieces, Lunar Eclipse and Night Garden, Delft and the pale stoneware Paradiso di Flora?

Again, I was inspired by Dutch Master paintings.

At Ceramic Art London, I designed my stand to show the pieces, one side in black and the other side in white clay, the mirror image of the same object in black and white.

Black clay has a totally different feel to the white. Mysterious, dark and somewhat more intriguing. I want to experiment more with black clay in the future.

What are you working on the moment and are there any plants that you are particularly interested in working with and why ?

I am working on the pieces for my solo show in Tokyo happening at the same time as the Olympics next year. And from Spring onwards, I will be working on botanical pieces for my solo show at Tristan Hoare Gallery in London in November 2020.

I have been studying the school of Japanese old masters known as Rimpa which started developing from 15th century onwards, reaching a peak in the 17th century. Japanese paintings in general are very seasonal and plants and flowers are often the most significant subject of their paintings. I am interested in creating a British version of them with wild flowers and plants native to this country or popular cultivars from that particular era, perhaps.

Interview: Huw Morgan | Studio photographs: Huw Morgan | All other photographs: Kaori Tatebayashi

Published 14 December 2019

There was a heavy frost this morning and we were suspended for a while in a luminous mist. The wintry sun pushed through by lunchtime, the melt drip-dripping and the colour of thaw returning as the unification of freeze receded. Undeterred the Coronilla valentina subsp. glauca ‘Citrina’ emerged unscathed, liberating their sweet honey perfume in the sun.

We went on a hunt for flower to see what there might be left for the first winter mantlepiece. The pickings, now rarefied, feel held in a season beyond their natural life. A rogue Lunaria annua ‘Chedglow’ misfiring, but welcome for the reminder of the hot violet which you have to imagine as you move the seedlings around to where you want them to be in the autumn. My original plants, a dozen grown from seed two years ago, are now gone. Last year’s pennies threw down enough seed immediately beneath to need thinning and the transplants allowed me to spread a new colony along the lower slopes of the garden. Being biennial, it is good to have two generations on the go so that there will always be a few that come to flowe,r but enough to run an undercurrent of lustrously dark foliage in winter. It is never better than now, revealed again when most of its companions have retreated below ground.

The reach of the Geranium sanguineum ‘Tiny Monster’ is now pulling back to leave a shadow where it took the ground in the summer. It has been flowering since April, brightly and undeterred by all weathers. This larger than life selection of our native Bloody Cranesbill shows no signs of stopping as the clumps steadily expand. It is a slow creep, but a sure one. Short in stature at no more than a foot, you have to team it carefully if it is not to overwhelm its neighbours. We also have the true native G. sanguineum, grown from seed collected from the sand dunes on the Gower peninsula in Wales, and teamed with Rosa spinosissima from the same seed gathering. The two make a fine match, the geranium scrambling through the thorns of the thicket rose.

The pink Hesperantha was a gift from neighbours who gave us a mixed bag of corms including the earlier flowering H. coccinea ‘Major’. This hot red cousin flowers when there is heat in the sun, but gives way to this delicate shell-pink form (which we think is most likely to be ‘Mrs Hegarty’) as the days cool in October. I am not a fan of delicate pinks, preferring a pink with a punch, but it is hard not to love this one when it appears. I like it for standing alone at this time of year and for not having to compete for being so very late in the season. In terms of where they like to grow though, Hesperantha hail from open marshy ground in South Africa so you have to find them a retentive position with plenty of light to reach their basal foliage. I have them on the sunny side of Aster ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’ which they come with and then go beyond.

Equally hardy, and one of the longest-flowering plants in the garden, is the Scabiosa columbaria subsp. ochroleuca whose delicate pinpricks of lemon yellow are held high on wiry stems and are still enlivening the skeletons of Panicum and Deschampsia that are now collapsing around them. Even now they are a magnet for the hardiest bees and the odd peacock butterfly that ventures out in the weakening winter sun before hibernating.

Aster trifoliatus subsp. ageratoides ‘Ezo Murasaki’ is our very last aster to flower, but its season is still longer than most. I love its simplicity and soft, moody colour, but it has been out for so long now that sometimes I forget to look. This is one of the joys of the mantlepiece and of hanging on so late to make you refocus. Not so Rosa x odorata ‘Bengal Crimson’, for it is hard to pass by this strength of colour in the gathering monochrome of winter. I have given our plant the most sheltered corner I have, because it is always trying to push growth which gets savaged by cold winds. Here, in the lee of the wall at the end of the house, it flowers intermittently, often through January, paled then by the cold, but always welcome. Close by and also basking in the shelter of the warm wall is Salvia ‘Nachtvlinder’, another plant that would continue to flower uninterrupted if we did not have the freeze.

Next year I will protect the spider chrysanthemums, which come so late and need it to survive the frosts. This is one of the few that have survived the recent cold spell. I have not grown ‘Saratov Lilac’ before, but have taken cuttings which are in the frame to try again next year. I have also ordered several more to test my end of season resolve and hope a make-shift shelter of canes and sacking will suffice when the weather cools in October. We got away with it when I grew them in London, but not here where the frost is reliable and helps us to respect the season.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 7 December 2019

So here we are with the last few leaves on the branches, poised on the edge of winter. Now we can see through the wood that provides our backdrop, there is just the faintest undercurrent of gold where hazel and field maple have hung on in the shelter. The stream is full and racing. The ground charged from weeks of what is now beginning to feel like an endless rain.

The garden has been wonderful this last month and arguably as good it ever was at its flowering peak. There are just a handful of flowers left now that the frosts have had the Nerines. Paled by the cooling nights and their diminishing energy, the last of the Asters hum a last wave of violet and, though the Tricyrtis no longer have their poise and skyward facing vitality, they remain beautiful in their death throes.

The frost has been the gamechanger. It melted the fleshy nasturtiums and crumpled the Aralias, their lushness culled in a night of cell-splitting carnage. Not everything reacted in the same way, but the greens altered immediately, colouring or browning or simply dropping to leave no more than skeletons and seed heads. Euphorbia cornigera reacted with a show of good colour, saffron and amber replacing the previously acidic greens. The frost was the trigger too for the reds and oranges in the Panicums. First the tips of the foliage, then the vibrancy travelling quickly down the length of the leaf so that they appear to glow from within.

The last of the autumn reveals daily differences, now that the grasses have paled and taken centre stage. These light catchers reveal themselves in plumage where the Miscanthus catch the backlighting on the dry days, but the very same seed-heads close tight and darken on the wet days, foliage that glowed an apricot warmth darkening to cinnamon. The Miscanthus are sure to stand the challenge of the winter ahead, but the same cannot be said for the Molinias. Teetering on the edge of falling apart – for they never last well when the winter wet gets into them – this is one of their best moments. The plants around and amongst them are suspended in a backlit veil of the finest filaments. Verbena macdougallii ‘Lavender Spires’ with its very last tips still coloured and Vernonia arkansana ‘Mammuth’ standing tall and dark, its plush seed heads aglow.

In contrast to this new luminosity, as the garden ages a complimentary darkness asserts itself where seed heads have come to fruition. Black lines score the vertical to make the Veronicastrum visible once again. I used them for their white line in the summer and now love them for this opposite. Though they are over now that they are stripped back for winter, they are far from spent.

Digitalis ferruginea are one of the best black verticals as they stand for so long, but the Agastache nepetoides are taller still and candelabra-branched. Like lightning conductors, they stand taut and pure in outline. Green in summer, they too are now more visible for their poker black spires. Easy to raise from seed it is worth having a number in hand, as they can be short-lived, and so I planted more for next year last spring. In part this was to combat the mice, which slowly carried away the seed heads in the course of a week once they had discovered them. I expect this to be their downfall again as the weather cools and the seed becomes worth the steeplejack journey the mice must have to make to retrieve it.

I will not go into the planting now other than to remove the odd broken stem where it might create a little discord. Sometimes it does make a difference and keeps things feeling buoyant a little longer, but it is hard not to see the coming season as anything other than beautiful. Eryngium seed heads, sculptural and as good in death as in life, Sanguisorba, drained of summer colour, their lofty scatter of darkness thrown into relief by glowing grasses. A million shining stars in the Aster seed heads, reminding you of their namesake.

Walking the garden daily we have seen an increase in the number of birds skittering across the path or flurrying upwards from where they have been foraging for seed. It is a good time to look and plan adjustments whilst things are still standing. Or to simply look.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 30 November 2019

Burnished coppery

Illuminating darkness

Mother memory

Words and photograph | Huw Morgan

Published 23 November 2019

Yesterday we had our first snow. Just the briefest flurry, and it was too wet and warm for it to settle, but snow all the same. The colder weather demands something warm and hearty in the stomach and has finally given me the opportunity to make a long-planned silky soup from the coco beans that have been in the freezer since I harvested them over a month ago.

To date we have only ever grown climbing beans to eat fresh, but this year we grew a range of new beans, some of which I selected specifically for storing. At the end of the summer the bean which had cropped most heavily was ‘Coco Sophie’, a late 18th century variety which became commercially unavailable in 2006, and has only recently been re-introduced by The Real Seed Company. Due to the variety and quality of their seed, it has fast become our go-to seed supplier.

Coco beans are an old French large haricot type, producing shiny, round, creamy white beans with a texture comparable to normal haricot or cannellini beans. However, they are smoother and richer than either. The Coco de Paimpol, which is grown only in Brittany, has its own appelation d’origine contrôlée due to its incomparable texture and flavour. Although I had eaten coco beans in restaurants before and been struck by their silky texture, I had not, until this year, been able to find seed to grow them myself.

I picked the beans when semi-dry – which cuts down their cooking time significantly – and froze them immediately. However, they can be fully dried and then soaked before cooking. If using dried beans for this recipe 400g of dried beans will give a soaked weight of approximately 800g and, although you do not need to sieve the soup, it produces a superior result that is worth the little additional effort.

In my mind I had a velvety smooth, garlic-laden puree flavoured with woody herbs and a whiff of truffle. I had a recollection of having eaten something similar many years ago in Milan, as I associate it with distinct memories of risotto alla milanese, osso buco and whole pan-fried porcini.

A whole bulb of garlic may seem too much initially, but since it is simmered in the stock its strength is tempered and sweetened. The seasonal combination of sage and bay is warm and aromatic. Although we have several types of sage growing here, the most robust and best-flavoured variety is known simply as ‘Italian’, with large silver-grey leaves that are winter hardy and perfect for frying.

Serves 6

3 large leeks, white and pale green parts only, about 250g

3 tbsp olive oil

800g fresh or cooked white beans

1 bulb garlic

2 large sprigs of sage

1 large bay leaf

1.5 litres water or vegetable stock

Freshly grated nutmeg

Salt

Ground white pepper

12 large sage leaves

3 tbsp olive oil

Truffle oil

Heat the olive oil in a large pan over a low heat. Wash, peel and trim the leeks and slice them finely. Put them into the pan, put the lid on and sweat over a low heat for 10 to 15 minutes until translucent. Stir occasionally.

Peel and trim the garlic cloves and leave whole. When the leeks are cooked add the garlic, beans, sage, bay leaf and grated nutmeg to the pan with the water or stock. Bring to the boil and then reduce to a simmer. Cook with the lid on until the beans are soft; about 20 minutes if fresh, or 40 if dried and soaked.

When the beans are done remove the sage and bay leaves, then liquidise the beans and their cooking liquid with a stick blender until smooth. Then, if you want the silkiest smooth soup, push the puree through a fine sieve with the back of a metal spoon. Season with salt and pepper to taste.

In a small frying pan heat the second lot of olive oil. When smoking, fry the sage leaves in batches for about 10 seconds until crisp and just beginning to brown. Remove from the oil onto a piece of kitchen paper.

Ladle the soup into warm bowls. Drizzle over a little truffle oil and garnish each bowl with two fried sage leaves.

Recipe & Photographs | Huw Morgan

Published 16 November 2019

The first frost of the season came on the night the clocks reverted from summertime. On the still, bright morning that followed, it hung in the hollows, the first fingers of sunshine liberating plumes of mist. We walked down to where they were moving between the yellowed ash and buttery hornbeam to find the leaves falling wet with thaw. Autumn in fast forward now and glorious for it.

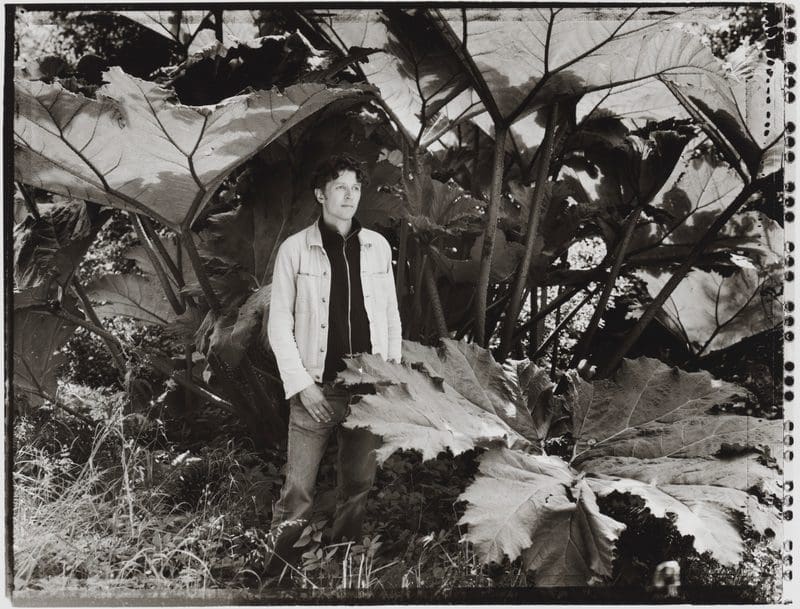

Walking back up the ditch to where I had feared the worst for the Gunnera, we found them still standing. Their huge rough leaves had bowed a little, but it was good to find they were still in one piece and that there was time to put them to bed whilst the foliage was intact.

I have a special relationship with these giants, which are splits from a plant I bought with my Saturday earnings, aged ten. The mother plant, which grew in the nearby combe, was a thing of pilgrimage and I would cycle there summer and winter to marvel at its transformation. It sat on a bank where a spring broke to form a little pond at the roadside. In the growing season the water would be all but invisible, dwarfed by the enormous splay of foliage. Broken by winter, a skeleton collapsed and rotting in the water, it struck a sinister mood and I loved it for that.

I wanted to have some really quite badly, to live through the giant’s rise and fall during a year and to grow myself a colony that, one day, I could get lost in. Our thin, acidic sand at the top of the hill was no place for it but, undeterred, I dug a pit and filled it with a plastic liner in readiness. It took a while to pluck up the courage to cycle there with a spade strapped to my bike and to walk up to a stranger’s front door to ask if I could buy some. I remember quite clearly offering the owner a ‘fiver’ and the surprise on his face (it must have been a good sum in the mid ‘70’s) as he said, “Yes. Help yourself !”. I have no recollection of wrestling a growing tip from the mud, but I do recall smiling all the way home with my hard-earned booty strapped to my bike.

Needless to say, and despite my attentiveness with watering, it didn’t do well until I found it a place in the overflow of the cesspit. Beth Chatto’s advice to “Feed the beast” was my inspiration and, as Gunnera really needs its roots in a steady supply of water, the richness here was the answer. In the years after I left home it grew and it grew and it grew and became quite the focal point in the orchard. Many years later when the photographer, Tessa Traeger, asked me to choose a place that meant something to me for a portrait I asked to be photographed beneath it.

So, after moving here, I was presented with the perfect opportunity to be reunited and relive the drama, the life and death throes of the giant rhubarb. Our wet, oozing ditch and boot-sucking mud where the springs burst from the hillside have made it the perfect home. I have planted about ten offsets which, five years later, are beginning to provide some bulk, since they take a while to settle. A little shelter from the wind provided by the crack willow sees it do best where the plants sit outside the canopy. They grow half as well and rangily in the shadows. Although they should easily double in size with time, the colony is already a place I have dreamed about for some time. A scale change in every way. Somewhere you can walk into and get lost in, the giant parasols throwing a green light as you move amongst them. The prehistoric foliage rasping and textured above you.

Hailing from highlands in Brazil, Gunnera manicata is all but hardy, but it is safest to protect the hoary crowns in winter. Old plants can come through a winter without a cloak of shelter, but two years ago in our heaviest winter here I lost all the main crowns where the frost hung in the hollows. Folding the foliage over the crowns, like a thatch or multi-layered hat is usually sufficient, but until my plants grow strong, they are insulated first with a layer of hay. Cutting the foliage before it is frosted allows for the sturdiest construction and there are few things as satisfying as winter draws close than putting these wigwams together. Protecting the beast for a sure reward once the clocks change again and it stirs from slumber.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 9 November 2019

Huw Morgan | 31 October 2019

It is almost three months since Flora first came to Hillside to work with material taken from the garden here. That summer visit was an introductory and learning experience for us both. Flora’s first time in the garden here, time needed to get to know the garden, time to find a setting to shoot in, the challenges of working outside and to be photographed in process when she is usually unseen, off stage. For me there was the self-imposed pressure to do Flora’s art justice in my photographs and to capture those moments of consideration, reflection, decisiveness, choice, care, which I was witness to as she worked.

As she worked this time I started to notice the ways in which Flora relates physically to the space in which the flower arrangement was being made. Standing with her back to me I could tell that she was judging, evaluating, balancing, deciding, framing, all of which could be read from the set of her jaw or the angle of a shoulder. The delicacy with which she would select a stem, find a location for it, and then gently and firmly aid and guide it into position. The final stroking of the plant to allow it to fall naturally and also the sensual pleasure of engaging with plants this intimately.

It reminded me of something Midori, the head gardener at Tokachi Millennium Forest said to us when she was staying here early last autumn, which is that the last flower arrangements of the year should be relished as they are the last opportunity for ‘touching green’ before the winter comes.

Flora Starkey | 1 November 2019

The last time I came to Hillside, Summer was making way for Autumn. This visit Autumn is peaking and the gardens are more subdued, but no less splendid.

We decided to shoot in the same location as before, in front of the beautifully rusted corrugated iron barn. I’m interested to see how the four images will sit together by the end of the year and like the idea of them being in the same place.

As before, we cut sparingly – no more than a few stems from each plant. This time I chose a lot of dried structure – dill, red orache, fluffy willow herb and a stem of Thalictrum ‘White Splendide’ with its delicate mottled yellow leaves. And of course, some essential autumnal colour in the form of Euphorbia cornigera and a snipping from the fiery Prunus x yedoensis.

Moving back to the barn, we pick some blue glass jars from the house & get to work. The space will always dictate the arrangement in terms of scale and the zinc table outside calls for size, not least because of the October wind.

The tall dried pieces were placed first creating the framework, a beautiful Aster umbellatus towering over the others. A few leaves of royal fern quickly followed, adding a myriad of colours in each stem. I carried on building the colour with warm tones before offsetting with the deep blues and violets of a few varieties of salvia.

Even though the stems keep get buffeted by the wind and moving around, I like this way of working. It’s spontaneous & can’t be too precious. After a while, I feel like we’re missing some pops of brighter colour and go foraging for rosehips, finding some spindleberry on the way.

As these are more structural branches, I end up taking the arrangement apart & starting again, adding these elements earlier. Some of the salvia had also started to wilt by the time we got back so we cut a little more. If I were to use this again, I’d try & sear it to make it last longer. I finish with a curling tail of yellow amsonia, a shock of pale yellow scabious and some shiny black berries of wild privet.

As well as wanting to represent the garden in all her autumnal glory, I was also keen to make a smaller and simpler arrangement – something quieter that allows the stems their space to shine. It’s probably how I’m happiest working.

The picture window outside the milking barn provides the setting and frames the vases with the changing landscape behind. I start with a length of old man’s beard and some more euphorbia. A few stems of panicum & chasmanthium add height along with a speckled toad lily. A sprinkling of dainty white asters were added lower down and some oxblood red leaves of fagopyrum trail off to the side, slightly broken but more beautiful for it.

Back in the garden & you can see the silhouettes of winter beginning to appear. Huw & I spent a little time looking at the plants that we’d like to dry and preserve for our next shoot. I’m looking forward to the change of the season already

Anethum graveolens

Aster umbellatus

Astilbe rivularis

Atriplex hortensis

Cercidiphyllum japonicum

Chamaenerion angustifolium ‘Album’

Chasmanthium latifolium

Euonymus europaeus

Euphorbia cornigera

Ligustrum vulgare

Lythrum virgatum ‘Dropmore Purple’

Osmunda regalis

Prunus x yedoensis

Rosa eglanteria

Salvia ‘Blue Enigma’

Salvia ‘Blue Note’

Salvia uliginosa

Sambucus nigra

Scabiosa ochroleuca

Thalictrum ‘White Splendide’

Thalictrum ‘

Aster unnamed white

Chasmanthium latifolium

Clematis vitalba

Euphorbia cornigera

Fagopyrum dibotrys

Oenothera stricta ‘Sulphurea’

Panicum virgatum ‘Heiliger Hain’

Papaver rupifragum

Rosa ‘The Lady of Shallot’

Salvia uliginosa

Tricyrtis formosana ‘Dark Beauty’

Tropaeolum majus ‘Mahogany’

Photographs | Huw Morgan

Published 3 November 2019

The autumn crocus appear late with the last of the asters and braving the change in the weather. Although I have only just planted the real saffron crocus, Crocus sativus, and wait to see whether it can handle our moist Somerset loam, I can now say squarely that I can depend upon Crocus speciosus, which are beginning to naturalise on the bulb bank behind the house. This year they came in the first two weeks of October during a fortnight of rain and heavy skies that accelerated the feeling of the evenings drawing in, but their appearance completely runs against the retreating tide and the feeling that goes with it.

Triggered by the very cool and the damp in the ground that puts an end to the growing season, they score the palest lilac tapers into the grassy banks. The true colour of the interior is suggested, but held back on the reverse when the buds are closed, but opened by sunshine or the warmth of a room if you pick one, they flare a bright lilac. Look inside and the violet tracery of dark veins maps an upward movement, the orange styles, luminous and hovering in a pool of colour. Look deeper and the dip of a yellow throat appears to throw light from this inner world.

Seen from the kitchen that is dug into the hill at the back of the house, the crocus appear just above eye level where I have planted them in an extensive drift. Standing tall at around 20cm, the stems push the flowers free of the meadow, which was cut late in August to make way for their arrival. The stems are impossibly delicate and, grown in an open position, they will easily break, not completely, but enough to topple the flower so that it lies fallen by those that have yet to do so. Planted in grass, which by October is grown just enough to support them, the majority stay standing and you can rely upon their display. A gentle autumn is what they enjoy most of course, but their emergence is always late enough to catch the turn in the weather.

Native to Greece, northern Turkey and Iran, the hot dry summers put the bulbs into ensured dormancy and a wet autumn triggers growth. Here they are best in a position that emulates their homeland and dries in the summer months and hydrates again in the winter when their foliage comes above ground to feed. A position under deciduous trees, where light comes to earth in the winter and the rootiness of ground dries in summer is ideal. Turf or meadow that remains uncut until their foliage withers in spring will also protects them during dormancy. If you are introducing the bulbs into turf, do so early in the bulb planting season to allow for their rise to October flower. Planting deep, up to 12cm, will also help keep them out of reach of mice, which are a favourite predator.

In the garden proper, I have been slowly introducing the white form, Crocus speciosus ‘Albus’, in areas that are sheltered from wind. In the lea of the barn where the low ground cover of violets and Waldsteinia ternata protect winter cyclamen, I have found them a niche. The white form is more ethereal still than the true species. Simpler for being white inside and out, but still with the charge of the orange style and the yellow throat, they are worth devoting a corner to for late season contemplation. Their grassy foliage with its silvery midrib comes in early winter and makes a pretty addition and complement to the marbling of the cyclamen leaves. Something to look forward to and to rely upon as the days shorten.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 26 October 2019

Bonfire night embers

Candy floss toffee apple

Flaming katsura

Words and photograph | Huw Morgan

Published 19 October 2019

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage