Thank you all for joining us here in this most challenging and difficult of years. Your engagement, encouragement and support have been a big part of what has helped us get through the past months. We are taking a short break, but look forward to joining you in what we hope will be a brighter 2021.

Once upon a time I had a very sweet tooth. Each Christmas Eve, close to midnight, as my overexcited brother and I lay feigning sleep in our bunk beds, dad would come and lay something heavy at our feet. We knew exactly what it was, and it called on all our reserves of self-control and superstition to prevent ourselves from peeking until it started to get light. When we did – and my younger brother was always the first to crack – we would haul the stockings (actually dad’s nylon football socks) up the bed and start to unpack them. Always alongside this stocking was another made of net. A Cadbury’s Christmas selection pack containing the usual suspects – Mars Bars, Twix, Milky Way, Marathon. We would slowly eat our way through these on Christmas morning and still somehow have room for lunch.

As a child I was always more interested in what was for ‘afters’ than the main event and my favourites usually involved chocolate, whether it was Bird’s Angel Delight, mini rolls, steamed chocolate pudding, Viennetta ice cream or choc ices. At around the age of 9 I started baking my way through the Marguerite Patten recipe cards mum had collected and which sat in a specially made plastic box on top of the fridge freezer. Once I had become proficient with scones, jam tarts and sponges, I quickly moved on to Devil’s Food Cake, chocolate Swiss Roll, Black Forest Gateau and, eventually, eclairs and profiteroles. My pièce de résistance, however, was Marguerite’s Pots au Chocolat, which to me looked impossibly chic in the photo on the front of the card. The dark, velvet mousse in simple, white porcelain pots, decorated with elegant quills of dark chocolate. It made me feel very grown up the first time I served them. Looking back for that recipe now I find that they contained melted marshmallows. Certainly not the purist’s idea of this classic French dessert, but one that, as a child, I was more than happy to accommodate.

As the years passed my palate became more refined. I graduated from Cadbury’s Dairy Milk to Bournville, from milk to dark chocolate Bounty bars and got a taste for Fry’s Chocolate Creams from my dad. (Mint, since you ask.) At university, I discovered Swiss and Belgian chocolate before, in my mid ‘20’s, experiencing a revelation. I had moved into a house on Bonnington Square in Vauxhall and, unbeknownst to me, my new landlady was about to change my view of chocolate forever. She was Chantal Coady who, in 1983, had opened Rococo Chocolates on the King’s Road. There were four of us renting rooms there and every month Chantal would bring home a box of ‘bin ends’, broken bars and trial new products from the shop and invite us for a chocolate tasting.

This may conjure images of a craven orgy of chocolate bingeing, but quite the contrary. The room was candle lit, a fine cloth on the dining table and a small selection of wines and spirits were available to be sipped in recommended partnerships with some of the ‘sweets’. Chantal would break small pieces of chocolate onto plates and pass them round. We were instructed to place the chocolate on our tongues and to allow it to melt slowly – no chewing! – and to describe the flavours we were tasting. Chantal explained how fake vanilla, hydrogenated oils and sugar destroyed the true nature of chocolate and would get us to compare my childhood Dairy Milk to a high cocoa content milk chocolate to understand what she meant. She taught us to appreciate it like fine wine and I have never looked back.

Christmas always calls for chocolate, but as I have aged my taste for sweet things has tempered and I have decreased the amount of refined sugar I eat. I rarely order pudding in restaurants these days unless I am prepared both for the initial sugar rush and the almost immediate headachy comedown. At home, dessert usually takes the form of stewed fruit or a handful of figs or dates, rather than anything sweeter. But it’s Christmas and I want chocolate, so I worked on this dessert recipe without refined sugar.

The combination of pumpkin and dates in the filling means that it needs no further sweetening, although if using chocolate with more than 82% cocoa solids you might want to and add honey or another sweetener to taste. If possible, use a drier-fleshed variety of pumpkin, otherwise you may need to drain the flesh before using as you don’t want the filling to be too wet. The Kabocha pumpkin I use has the texture and flavour of chestnuts, which makes it particularly truffle-like.

Chantal was also a pioneer in the use of unexpected flavourings and this tart is also the perfect foil for your favourites. To my knowledge, she was the first to make cardamom flavoured chocolate, to which she introduced me and which is my habitual choice. However, you can infuse the milk and cream with any winter spice or herb you like. Bay is very good (a couple of leaves), or try a sprig or two of rosemary or thyme, a spoonful of ground fennel seeds or even some crushed juniper berries. A teaspoon of finely ground espresso coffee heightens the bitterness. Half a teaspoon of chilli powder warms the mouth and accentuates the flavour of the chocolate, while a few drops of rose or rose geranium oil add a different level of perfumed refinement. The addition of a couple of tablespoons of alcohol – rum, for instance – makes it definitely adults only. Although we have been eating it plain this week, for a truly festive plate this would be particularly good with brandy-soaked prunes or figs or pears poached in white wine. Definitely a chocolate dessert for grown-ups, not children.

Serves 12

Pastry

75g hazelnuts

150g plain flour

1.5 tablespoons honey or maple syrup

75g cold butter

1 large egg, beaten

A pinch of salt

Filling

200g cooked pumpkin

100g dates, chopped

100ml milk

250ml double cream

3 large eggs

200g dark chocolate (minimum 70% cocoa solids)

Seeds from 3 cardamom pods, finely ground or other chosen flavouring

You will need a 23cm round, fluted tart tin with a removable base.

Set the oven to 180C.

Put the hazelnuts into a small baking pan and put into the oven for 10 minutes until lightly toasted and fragrant. Remove and allow to cool, then put into a food processor and process into a medium-fine flour. Do not over process or you will end up with nut butter.

Add the flour to the hazelnuts and pulse mix. Cut the cold butter into 1cm cubes and add to the flour and nuts. Pulse again until the mixture resembles breadcrumbs. With the motor running slowly add the beaten egg and honey until the dough comes together. Stop the machine immediately and quickly remove the dough. It will be very soft. Form into a ball, wrap and put into the fridge for 30 minutes.

When the pastry has chilled, roll it out carefully on a floured surface until large enough to line the tart tin. The pastry is very short, so work quickly and carefully. However, if it falls apart just fit the pieces to the tin and press together gently to join. Trim the excess pastry from the rim allowing a little extra for shrinkage, line with greaseproof paper and fill with baking beans. Bake blind for 20 minutes. Remove the baking beans and greaseproof paper and return to the oven for a further 5 minutes until it looks dry. Remove from the oven and allow to cool.

To make the filling heat the milk and cream in a small pan. Grind the cardamom seeds to a fine powder in a mortar and pestle and add to the milk. As soon as the milk comes to the boil remove from the heat, add the dates put a lid on the pan and leave to stand until cool.

Chop the chocolate coarsely and put into a heatproof bowl. Put into the oven for about 10 minutes until almost melted. Remove from the oven and then beat with a fork to ensure that all of the chocolate is melted.

Put the cooled dates and cream, eggs and pumpkin into the food processor and process until smooth. Add the chocolate and mix until fully combined. Pour the mixture into the prepared pastry case and bake for 30-40 minutes until the mixture just starts to crack at the edges, but still has a little wobble in the centre.

Leave to stand for 20 minutes before removing from the tin and transferring to a serving plate. Decorate with sieved icing sugar as you wish.

Serve warm.

This reheats and freezes well.

This can easily be made suitable for vegans, using coconut oil and sugar in the pastry. For the filling substitute the milk with vegetable milk, the cream with an equal weight of silken tofu (although do not heat this with the milk). Substitute the eggs in both pastry and filling with chia ‘eggs’ (1 tablespoon ground chia seed mixed with 3 tablespoons cold water for each egg).

Recipe & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 19 December 2020

The Iris unguicularis arrive at precisely the moment it becomes apparent that winter is here to stay. Spearing clear of their strappy foliage whilst the world around them is in retreat, the tightly rolled buds provide untold good feeling. Their intermittence is welcome, the flowers appearing in the mild weeks and not in the cold ones from now until February snowdrops.

Although I have never seen the Algerian iris growing in the wild, I hanker to do so. To follow them one day on a journey through Greece, on into Turkey and all the way through to Tunisia. It would be good to see exactly where they grow in these rocky landscapes and why the best advice in this country is to plant them at the base of a south-facing wall with their backs against the reflected heat and their foliage basking in sunshine. This was exactly how my great friend Geraldine grew them, close to but not in the shade of a twisted fig and with nerines that shared their need for a baking. This was a treasured spot in her garden and I remember her justifying their neglect as she pulled me up a piece one autumn, conjuring, as she did so, their homelands and intolerance of cosseting. No food, no water and certainly no shadow. They prefer, she said, to be growing in rubble.

Although I have long since lost the original plant she gave me when I was a teenager, I can see them like yesterday on her kitchen table. Plucked in bud, to get the benefit of a long stalk and savoured expectation, they sat on their own in December and then, as the winter deepened, with witch hazel, pussy willow and wintersweet. The pale buds, with their picotee edging and tease of the sumptuous interiors, unroll in a matter of minutes once brought inside into the warmth. If you are lucky, you will witness the unfurling, but unless you make the time the transformation happens when you have your back turned.

Up close and inside in the warmth, their delicate perfume makes you wonder why they are happy to live with our wet and grey, scowling winters. In the wild, of course, where wet days are reliably followed by a week of bright sunshine, they are forage for bees when little else is blooming.

The plants I have here in Somerset came by way of a gift from the great nurseryman Olivier Filippi. I had been tasked by the National Trust to re-imagine the Delos garden at Sissinghurst and I had gone to see him in France to seek advice about the best plants for the job. The climate near Montpellier could not be more different from Kent, with low rainfall in the winter and months without it during a long summer. The garden alongside the nursery is remarkable and it was here that I came upon the Algerian iris providing their bright wintery flower under pines on the periphery of the garden. It was a surprise to see them out of my imagined context, not amongst rocks, but growing through pine needles so, where we augmented the soil at Sissinghurst with 50% grit, I have experimented with them in a range of conditions, including open shade.

My plants from Olivier are his own selections, a pale mauve-pink called ‘Bleu Clair’ and the much darker ‘Lucien’ which is the bud we plucked today. The old gold reverse gives the merest hint of the darkly rich flowers in the finely drawn edge to the reverse of the petals. More readily available here is a fine form called ‘Walter Butt’, which is truer to the species and the colour of a clear wintery sky. I have this plant at the London studio and plan to bring some here and find it a place nearby so I can enjoy them together.

Here, on our hearty loam, I have not been tempted to grow them in anything but full sunshine for fear of our West country wet being their downfall. They are planted in a free-draining position, with plenty of air and paired only with plants that do not smother their growth in summer because their rhizomes need the opportunity to store energy for winter flower. Erigeron karvinskianus and violets make good company. I have also not been tempted to do as the books advise and cut their evergreen leaves in the autumn to reveal the flowers clear of their foliage. Although it is often described as tatty, I like the flowers sitting pure and wild amongst it.

So, here they are on the gravel drive to lighten our daily movements on this well-trodden path. When darkness descends and it is still the afternoon, these small things count.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 12 December 2020

The shift has happened. Last leaves down to reveal the trunks and tracery of branches. Winter outlines and the definition of reading individuals, their structures and differing characters against the sky. Hidden by the cloak of the growing season, but ever present, is the ivy. Where it grows uninterrupted and using the frame of another tree to make its way, a shadowy presence or a life within throws its winter outline. Dark and glossy and a refuge for the birds.

The oldest plants sit just inside the halo of their host, the growth becoming arborescent once it meets its reach. The mature ivy wood is entirely different from the juvenile, branching like antlers and without the need for the suckers that attach the young plant on its ascent. This wood, throws flowers in November, the very last forage for bees, and then goes on to weight itself with darkening, inky green berries. Fruits that at the very end of winter are ripe and ready for hungry birds. If you propagate the arborescent wood, the resulting plant retains this character and makes a fine winter evergreen if you grow it without the temptation of a support nearby. A wall or a trunk will trigger its innate desire to climb and conquer and it will revert to type if it senses an opportunity.

There are mixed feelings about the damage ivy can do. I prefer not to let it loose on buildings for it will forever be in the gutters and having a go at crumbly mortar and window frames, but I am relaxed about it growing into trees. That said, a mature plant can eventually bring a tree down, the weight of foliage providing a sail the host had never allowed for. We have an old hawthorn in the top hedge and at this time of year you can see it is more ivy than tree. Every year after a winter storm I expect it to topple, but I am happy to see the association for now striking a balance and making more of the hawthorn. Walk by it now the foliage is down elsewhere and it is alive with chatter.

Look into the winter hedges and you see that they are also laced throughout with ivy, which in turn provides the hedges with a winter opacity and shelter. The seedlings arrive there from the birds that have gorged upon a mother plant and then paused to poop and this is how they appear in the garden too. Showing you where the perches are and mapping the birds’ movements.

Holly does not do as well here in the hedges as it might on the lighter ground of acidic heathland. I have tried to introduce it, but the plants dwindle and have come to nothing, presumably due to our hearty ground and the advantage it gives to competition. The hollies do better here in isolation and out in the open and we have a pair of old trees by the potting shed that were planted when the land was once a market garden. A neighbour told us that the family who lived and worked here made Christmas wreaths from it for Bath market. Though it is now dwindling, this female tree is a good form, thornless and holding on to her berries for far longer than usual. Not far away in Batheaston a colony of suffragettes who lived in Eagle House planted a collection of hollies each one celebrating a woman who had fought for the cause. An emblem that perhaps also drew upon the ancient appreciation of the constancy provided by this plant and representing, in its winter steadfastness, an image of eternity. We wonder, a little romantically, if our plant might have originally come from the same collection and I have propagated autumn cuttings with the thought that she should have life elsewhere on the land and a new generation.

Unless you specifically buy a named female or a self-fertile tree such as ‘J. C. Van Tol’ it is pot luck whether you have bought a female or a male. Though one male can service many trees and from quite some distance when the bees are active, I have planted tens in groups where the sheep cannot get to them. One day, for they are slow, I hope they will provide our land with some weight and heft of winter evergreen.

Just this year, seven years after planting, the females are beginning to fruit. Bright and clean. Red against ink green, foliage shimmering, the leaves as reflective as mirrors when basking in winter sunshine. It is then, in this stark season that you see the holly in another light altogether. Not a tree of darkness and sobriety, but one of light and joyfulness.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 5 December 2020

On Thursday this week the temperatures plummeted and, with torch in hand, I spent an hour before bedtime throwing fleece over the tender plants that hadn’t quite made it to their winter quarters. The old brugmansia that has lived through the last twenty five years of seasonal upheavals, the uprooted dahlias waiting in the barn to be potted up for storage in the toolshed and the pelargoniums on the veranda that were brought together in a huddle earlier in the month. A few last days in the open air before they have to come indoors.

It was an hour well spent and, sure enough, the next morning a proper frost lapped white to the very walls of the house. The following day was as clear and as beautiful as any day could be in the very last moments of autumn. Light poured luminously into a garden united by the freeze, the colour of spent stems and withered foliage sitting under the silver, knocked back but still in evidence. The open skies remained clear and late after supper, we ventured out with hats and a torch to look at the garden as the freeze came in again. Spangled and glistening and still.

First frosts always feel cleansing. They finish one thing and begin the next. Last leaves dropping in the thaw the next day and trees newly naked. Views again through the woods, the ferns shining on the floor, no longer in shadow but revealed by first winter sunshine. A frost opens a window for winter work. With the fruits ‘bletted’ by the freeze, berries are eaten fast in the hedgerows. Roesehips first, the shiny black privet hanging on a while yet. When we can see the cycle is complete, it is time to cut the hedges that mark the tended places close to the buildings and provide the contrast to the rough wild hedges that run away darkly and on into the valley.

The link between garden and the beyond landscape is deliberately mutable and I prefer to tread lightly now and to only act where it is really needed to keep in time with the landscape. The garden is left now to fall away and reveal itself in its skeletal form. Leaves allowed to fall to earth and become a protective eiderdown, pulled under eventually by the earthworms when the time is right. The joy then in the winter forms, some of which are here just for a while in our West country wetness which will topple the molinias by the end of December. Those with the stamina to stand a little longer will reveal the life that is still occupying the garden. A lattice-work of interconnected cobwebs and seed that is slowly stripped by the flit and flurry of birds.

This year the bolt uptight pokers of the Agastache nepetoides have already been dismantled by what we imagine must be field mice. We have not seen them doing it, but it is quite a feat of agility, running the lofty mast to the bounty at the top, cleanly decapitating the seedheads and then taking them back down to earth. Do they throw them from the top, I wonder, or carefully carry? We have never found the evidence.

The feeling of stepping back in order to look ahead feels right just now. Letting the occupants of the garden partake where they need to and only applying our energies strategically. The beginning of the winter work has started. This year the cutting dahlias have been lifted rather than left in the ground to make way for tulips and a change, but the species dahlias are left in the ground to tough it out with a little protection. A bucket of compost heaped over their crowns now that their tops are blackened will see them through. The same goes for the tender Salvia patens, which also has a tuberous root and the potential to be completely perennial given a little help. Slowly, planning the weeks ahead before it all starts again, we will pace ourselves. Emptying the compost heaps, planting trees and hedges and beginning the first of the coppicing. New weeks, stripped back by a landscape resting and the chapter unfolding ahead of us.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

28 November 2020

The gales have torn at the last of the autumn colour, the rain is with us again with apparently no let-up, but open the door to the polytunnel and you enter a world that is stilled. Immediately calmed and weather-protected. The drum of the storm amplified yet distanced.

This is a place we are getting to know and learning about through growing. Ordered in the first lockdown and erected just before we came out of it at the end of May, the summer’s crop of tomatoes, cucumbers, basil and chillis is now replaced by winter salad. Hunkering down in an environment that takes more than the edge off the winter, we can already see the benefits in the enabled growth. The complement to the hardy winter vegetables in the kitchen garden.

The polytunnel is also providing sanctuary for another crop we are growing to keep us buoyant as the evenings lengthen and the growing season retreats for good. Brought inside at the beginning of October to escape the elements, the spider chrysanthemums are at their very best and, indeed, most vulnerable as the weather turns. Though I grew them successfully for a couple of years in the microclimate of our London garden, last year’s attempt at growing them outside here ended in tears. Months of care and promise were destroyed by November frosts, the very first flowers left in ruins and buds blackened beyond hope.

Not to be daunted, an order was placed with Halls of Heddon last year without a specific plan for their autumn protection. Such is the way with failure in a garden, it often spurs you on to succeed. The rooted cuttings arrived in the spring, this year with the promise of the polytunnel as an autumn retreat, so they were potted on and placed in the lea of the barns up in my growing area. Here, they received morning light – the four to six hours they need to set flower – and then afternoon shade. They were carefully staked and given not much more attention than a regular liquid feed to help flower production.

I confess to preferring plants that one can nurture towards independence to those that are reliant on human intervention, but the chrysanthemum festivals in Japan are enough to subvert my self-imposed rules. Once the leaves are down on the fiercely coloured maples and twiggery presents itself again to grey skies, they take a special place in the descent into winter. Grown often just one flower to a stem, displayed on a plinth and often against a dark backdrop, the blooms are naturally likened to fireworks.

My plants this year have, by contrast, been neglected. They were not pinched out to promote appropriately spaced branching, nor dis-budded to select a number that can put all their energy into flower. They have had the minimum of care. A chrysanthemum grower would say mistreatment. But here they are, in the shelter of the polytunnel, coming into their ethereal own as the rest of the world outside begins its slumber.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 20 November 2020

One of the benefits of working from home in Somerset this year is the time we have gained to harvest. Previously, there has always been a disheartening moment in late summer when it becomes apparent that there simply aren’t enough hours to get everything in the kitchen garden gathered, processed and stored away for winter. In the past, to dispel the phantom of wastage, we have managed this in a number of ways. Firstly, by inviting friends down for harvesting and preserving weekends – which has clearly not been possible this year – giving away the surplus to neighbours or leaving it out for passers-by or, finally, satisfying ourselves with the knowledge that what we can’t eat will be gladly seized upon by birds, rodents, insects and gastropods.

Though we blanched and froze enough French beans, broad beans and cauliflower to provide for us through the winter, it quickly became apparent that our harvest of soft and stone fruit would soon fill both freezers. Knowing that when everything else started to come on stream the question of what to do with it all would present itself, I prepared myself by reading Piers Warren’s How to Store Your Garden Produce and its American equivalent, Keeping the Harvest by Nancy Chioffi and Gretchen Mead. Both books give detailed instructions on how to freeze, salt, dry, bottle, ferment, pickle and preserve any fruit or vegetable you care to name.

My primary concern was for the tomatoes, of which we had a lot and of which I was determined to ensure not a single one was wasted. The idea of having our own supply of tinned tomatoes and passata – some of the few things I still buy from a grocer or supermarket – led to a frenzy of bottling in August, and the pantry shelves soon groaned with jars of whole and chopped plum tomatoes and bottles of passata. In Italy what I produced would strictly be called tomato sauce, as I learned that true passata is actually raw, with whole tomatoes being put through a passa pomodoro (tomato mill) that separates the skin and seeds from the pulp. The raw pulp is then put into sterilised bottles, the only cooking being from the time spent in the sterilising water bath required to preserve them.

I cooked the tomatoes and simmered them until there was no excess water content before passing through a mouli-légumes and then bottling with a dash of salt and citric acid to aid preservation. A late summer glut of cherry tomatoes resulted in a further 5 kilos of bottled, whole tomatoes, as well as several litres of yellow tomato ketchup, made using an adapted recipe from Kylee Newton’s The Modern Preserver.

In anticipation of this year’s bumper harvests, in May I had decided to invest in a dehydrator. When I could see that space in the pantry was soon going to run short it came into its own. For several weeks in late August and September it saw an almost permanent relay of pears, plums, blackcurrants and raspberries, but mostly many kilos of tomatoes. The benefit of drying, of course, is that the resulting produce takes up less space. It is also much lighter to store and concentrates the flavour, so a little goes much further when you come to cook with them. Most of the dried tomatoes are stored in an airtight bucket with a lid, but I have also preserved some under oil with bay, thyme and garlic cloves, to eat as savoury snacks or used to enrich other dishes.

The last of the tomato preserves came about more from necessity than design. I was completely out of shelf space in the pantry and yet there were still kilos coming up from the polytunnel. So, having gone through the same initial process as for the ‘passata’, the resulting sauce was reduced over a low heat until thick enough to spread out on greaseproof paper and put into the dehydrator. By the end of the next day I had enough small jars of tomato concentrate to see me through a winter of casseroles, soups and sauces.

It was just last weekend that we harvested the very last of the tomatoes from which we made about 5 litres of tomato soup. Given heat by the addition of some chilis also grown under cover this year, it warmed us through a whole week of sunny but chilly outdoor lunches. The thing that really makes me glow, though, is the prospect of opening a jar of my own plum tomatoes in January or February and bringing a memory of summer’s richness to the depth of winter.

Words & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 14 November 2020

As if in sympathy with the sicknesses, both physical and political, which have dominated the world since the beginning of the year, the kitchen garden got off to a half-hearted start this spring. The broad beans and peas were ravaged by mice, chard and brassicas were mildewed and slug-devoured and far too many of my first sowings germinated badly. The most concerning of these was the celeriac, which is a staple for us in the winter. We habitually plant 20 plants and eat them all.

Celeriac seed is small and notoriously erratic as it needs light and early warmth to germinate. It also has a long growing season and so needs to be started off in early spring indoors, under glass or in a heated propagator. We waited more than three weeks for ours to appear on a bright windowsill, before finally admitting that they probably weren’t going to. And so, in the knowledge that we simply couldn’t survive a winter without, I resorted to ordering some young plants from an online supplier. We hardly ever do this, but I am always grateful that they exist as you are effectively able to buy time and plug any gaps in the garden that might have appeared through misfortune or mismanagement.

However, what you do not have from mail order suppliers is control over the varieties, and I was obliged to buy ‘Giant Prague’, when our proven variety of choice for many years now has been ‘Prinz’. We have never had a problem with ‘Prinz’, which has been easy to grow and a reliably heavy cropper, with roots of a kilo or more being standard. So I have been keeping an eye on the newcomers this summer to see how they compared. I quickly noticed their different growth habit, as they are much taller, more upright and leafier and so have shaded the plants behind more than the lower growing ‘Prinz’. In late summer I also became aware that the roots were not bulking up as noticeably, despite the heavy watering that they like and regular feeding.

When I went to dig the first of the celeriac for this recipe this morning I was not impressed to find that several of the plants are bolting, and so have useless withered roots, and that the plants in the back row, in the deepest shade, have also failed to swell. Immediately the number of meals we have counted on them to provide is probably halved. Somewhat disheartening after all the effort and the ground given up for a disappointing crop of something we have taken for granted. At least it was good to know that I would be making the roots go further with the addition of chestnuts and windfall apples.

In the orchard the apple ‘Peter Lock’ has held onto its fruits the longest of all. This West Country variety has a long season of ripening, and so there are still apples on the branches that won’t fall no matter how vigorously you shake. The ripe windfalls are cushioned by the long grass of the pasture in which they grow and so, if you can get them before the mice, jackdaws and wasps do, they are seldom badly bruised or damaged. ‘Peter Lock’ is a dual-purpose eating and cooking apple with creamy white flesh. It is tart, yet sweet, and makes the most delicious golden apple puree which we always have a container of in the fridge, both for breakfast or evening dessert with yogurt or cream respectively. The large fruits also store well into the new year.

Our late spring frost on May 12th means we are without chestnuts this year, but the tree that Dan planted in memory of his dad has thrown out some good growth without the energy going into fruit so we hope, frost permitting, for a crop next year. Celeriac has an affinity with many nuts, particularly walnuts, hazelnuts and pecans. Here seasonal chestnuts enrich and thicken the soup. Wild mushrooms would be an appropriate addition. Rustic shards of bread fried in olive oil would provide textural contrast. The addition of cooked pearl barley would make it more substantial and go further. It would take well to the addition or substitution of other warming herbs and spices including rosemary, thyme, sage, winter savory, nutmeg and mace.

750g celeriac, after peeling, coarsely cubed

1 medium onion, peeled and coarsely chopped, about 200g

350g cooking or eating apple, peeled and cored and coarsely chopped

300g cooked chestnuts

2 bay leaves

8 juniper berries, crushed

2 cloves garlic, finely chopped

A 2cm length of fresh ginger, peeled and finely grated

50g butter

1 litre hot vegetable or chicken stock

Heat the butter in a large, heavy-bottomed saucepan until foaming. Add the onion and stir to coat thoroughly. Put on the lid and leave on a low heat to sweat. Stir from time to time and cook until translucent and golden.

Add the celeriac, garlic, juniper, ginger and bay leaves to the pan, stir everything together, and return to a low heat with the lid on. Stir from time to time and cook for around 15 minutes, when all should smell fragrant and the celeriac is starting to become translucent at the edges.

Add the hot stock and chestnuts, stir and return the lidded pan to the heat. Cook very gently for about 40 minutes until the celeriac is soft.

Add the apple and cook for another 10 to 15 minutes until it starts to break down.

Remove from the heat and use a potato masher to roughly smash the mixture into a course soup. Season generously with salt and black pepper.

Recipe & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 7 November 2020

At the bottom of our hill, where the stream runs along our boundary, everything changes. The stillness there is a constant, even on the days when we descend the slopes to escape being buffeted on the higher ground. Although it now stands tall, the wood that runs our neighbour’s boundary is not so old. Glad, who lives just behind us remembers being able to see the slopes on the other side when she was a girl, eighty or so years ago but you can see signs of ancient woodland in spring mapped in colonies of wood anemone, bluebell and, in one place, herb Paris in the places where it must have stood for longer.

It is interesting to imagine the push and pull that must have happened over the decades with the management of the wood and the open ground respectively. When we moved here ten years ago this very weekend, the land that runs down to meet the stream had been grazed hard and the ankle twisting ruts that the cattle had made in the clay ran up to a twist of barbed wire that hugged the stream edge. The battle the farmer had made with the wood to keep it back was traced in bluntly severed limbs and an ongoing tussle with the brambles that were leaping from the wood across the water. We made the removal of the wire and the encroaching brambles our first winter job, so that we could see the lie of the land and the path the stream had cut in the valley.

The following summer I fenced off the lower slopes of the Tump, tracing the line where the farmer dared go no further down the slope to cut the hay. The plan was to bring the wood back over the stream to our side in a swathe of trees for coppicing on an eight to ten year rotation for firewood. The young saplings were planted over four winters. Hazel made the foundation and the majority, whilst small leaved lime, sweet chestnut and hornbeam were added to ascend above the hazel for shade. Managed on a slower cycle of twenty years, the tall trees in the mix will make fencing poles and wood for the burner. The first hazel should be ready when I am about sixty and the larger subjects should be mature enough for their first cycle of copping when we are pushing seventy. A good incentive to stay nimble, but in the meantime a joy in the coming together of this new environment.

Seven or so years in and we are beginning to see the changes. The tussocky sedges that told us this was heavy, wet ground are slowly being shaded out, the advance of the wild garlic has begun stepping out from the small groups on the stream banks and the roosts and runs of the animals that live here are already in evidence.

I took time to look at the established wood to see which trees did best immediately beside the stream because without tree roots to hold the banks, we were vulnerable to erosion on our side. It is only where we have occasional alder that their thickly matted roots hold the stream banks sufficiently to bind them. The alder, however, are not shade tolerant and as streamside trees they would ultimately not be ideal in the coppice. The shade tolerant hazel do not have a root system that holds the stream banks, but looking at my neighbours mature hornbeam, it was clear that they were both good in shadow and also in holding the banks. Where they sit by the stream it moves around them and in the spring you can see the influence where the garlic laps up to their root plate to leave mossy circle free.

The fibrous roots of hornbeam (Carpinus betulus) can be hungry in a garden and you can see that alongside a hedge where company grows less easily, but for the streamside they are ideal. So this is where the majority have been planted and they have shown their tolerance of the thick heavy clay here too, throwing sturdy growth and showing that they have taken to their position.

I was brought up with the ancient hornbeam coppice that grow on the downland where I spent my childhood. Some of the old stands were hundreds of years old, the timber the fuel for smelting iron and making charcoal. Known locally as ‘bluntsaw’, for the wood is one of our hardest and consequently hottest burning, hornbeam has also been used for making yokes for oxen and clock parts for its strength and ability to withstand wear.

Currently, in this last couple of weeks of autumn, the hornbeams are flaring yellow so that you can see exactly where they are in the wood. As young trees in winter and cut to retain juvenile growth as hedging material, hornbeam retain their foliage. Russet brown and rustling nicely in wind, they provide fine protection for winter birds. Holding onto their seed late, they are hung with the papery bracts for some time yet before the windborne seed is liberated or eaten by the birds before it has a chance to spiral down. As hornbeam mature their trunks develop a smooth and undulating musculature which makes a coppiced tree all the better for winter interest in the wood. Spring is heralded in pretty catkins that festoon the branches with countless creamy verticals. April foliage is the brightest of greens and in summer the pleated leaves are host to a wide range of moths that use them as their food source.

Though in summer the canopy casts a dense shade, the elderly branches reach widely and elegantly and hold their own and very particular place in the wood. A hornbeam can live to three hundred years or longer if it is coppiced. They wear their age well so it is good when we see such progress to ponder the lives of our youngsters. Happy here it seems and making the place their own.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 31 October 2020

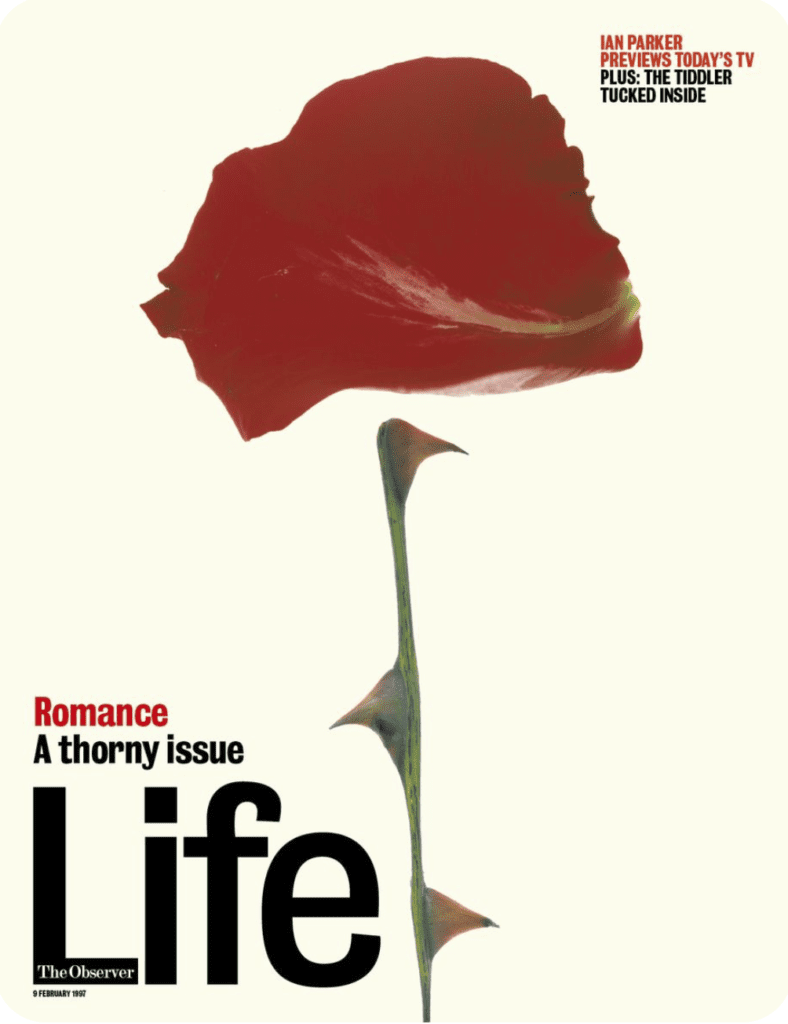

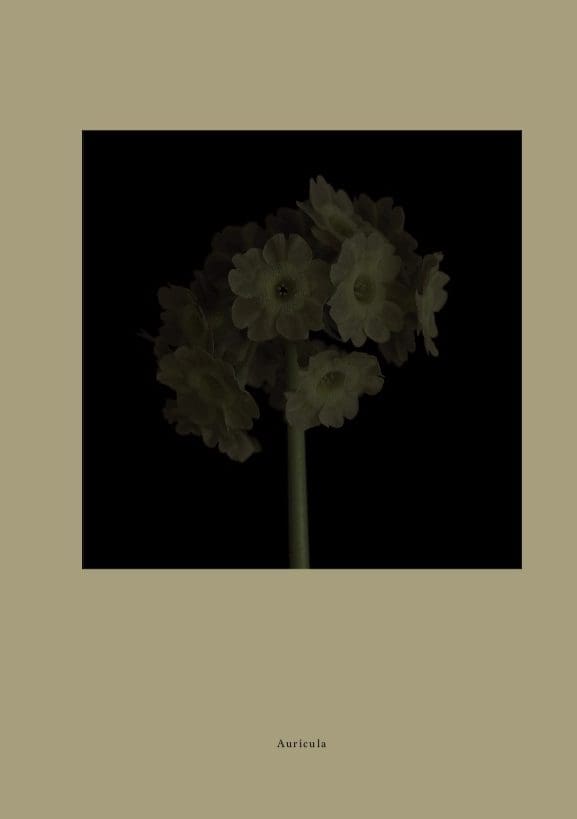

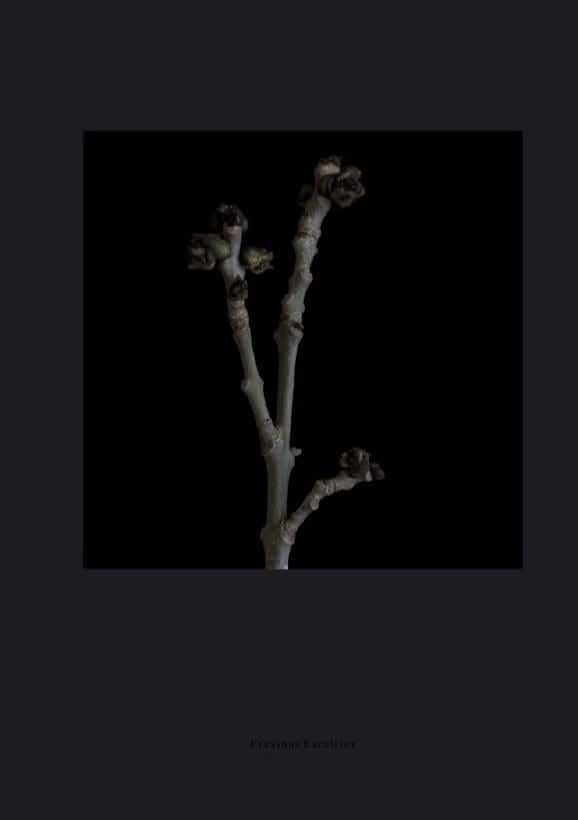

Fleur Olby first came to our attention in the 1990’s with her striking abstract plant portraits which illustrated Monty Don’s gardening column in The Observer Life Magazine. Her interest in shooting in low light prompted us to invite her to photograph the winter garden. So, early this year, and just weeks before lockdown, Fleur came to spend a day and a night at Hillside. As the clocks go back we revisit her vision of the penumbral garden.

Tell me about your interest in nature. When did it begin and were there any key experiences that shaped your relationship to the natural world and plants in particular?

During childhood I became ill with double pneumonia and had to be in an oxygen tent. My Mum brought an oak leaf into the hospital as a gift to look at something beautiful and magical from a tree close to where we lived and the thought of visiting it when I was better. I remember visiting the tree later, although now it all feels dreamlike. There was something then that I still question in the shift in perception of looking at something small in isolation to seeing it in its context of growing on a tree. The enlarged gaze of a child was full of wonder, magic and intrigue, something I have tried to recreate in my still life photography.

How did you realise you wanted to become a photographer?

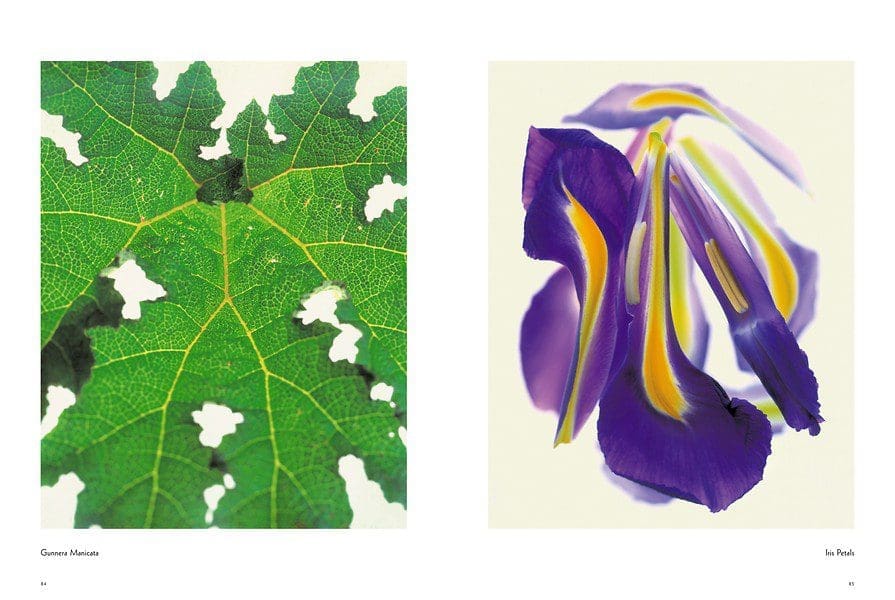

During my MA in Graphic Design at Central St Martins (1992), I spent a lot of time colour printing in the darkroom, my degree show became purely photographic – Images of environmental and flower still life. My thesis explored the different ways of looking at Nature from abstraction, the single image, still life, the object in its environment, the concept of the Wilderness and a Garden and their uses within the industries of Art, Design and Photography.

I wanted to be able to work within the landscape I grew up in and the magazine aesthetics of still life. At this time, I was entranced by looking at detail, but importantly when I first started making pictures in wilderness places there is an unexplainable feeling found through the camera.

Your work for The Observer Magazine was groundbreaking at the time. Can you explain how your view of plants differed from the norm then?

I was inspired by Monty Don’s writing and both degrees were fine art graphic design – lighting and composition were always experimental. Nick Hall was my first commissioning editor at the Observer and then Jennie Ricketts. He commissioned the garden articles to be an abstraction in still life. The concept of the garden as a still life representation was different then. It was a unique time when my imagery was young and given total creative freedom. For the articles, I would regularly be at the flower market at 4 am and in the lab processing the work at midnight ready for the morning.

Although you were working commercially what made your photography stand out then was that it was clearly the vision of an artist. Can you describe you and your photography’s relationship with the worlds of art and commerce and do you still produce commercial work?

I had a good mix of editorial design and advertising and the two books were the fine art application of my work. After the 2008 financial crash and the evolution of digital capture still-life Photography commissions changed and lifestyle photography replaced a lot of the still life work. After 15 years of commissioned work, I had to change my practice as it became unviable to run a still life studio. I consolidated my archives and started to make personal work. The series are ongoing, but I would also like to work on plant collections again and garden stories.

How did your work develop after your time at The Observer ? I have read that some of the images were used in installations. Now you produce limited edition imprints alongside prints.

The Observer gardening editorial was amongst editorials I contributed to regularly for food and health and beauty. When I stopped shooting for the gardening articles in 2002 the food still life increased and I also worked for some fashion companies for still life and jewellery, perfume and interior still life.

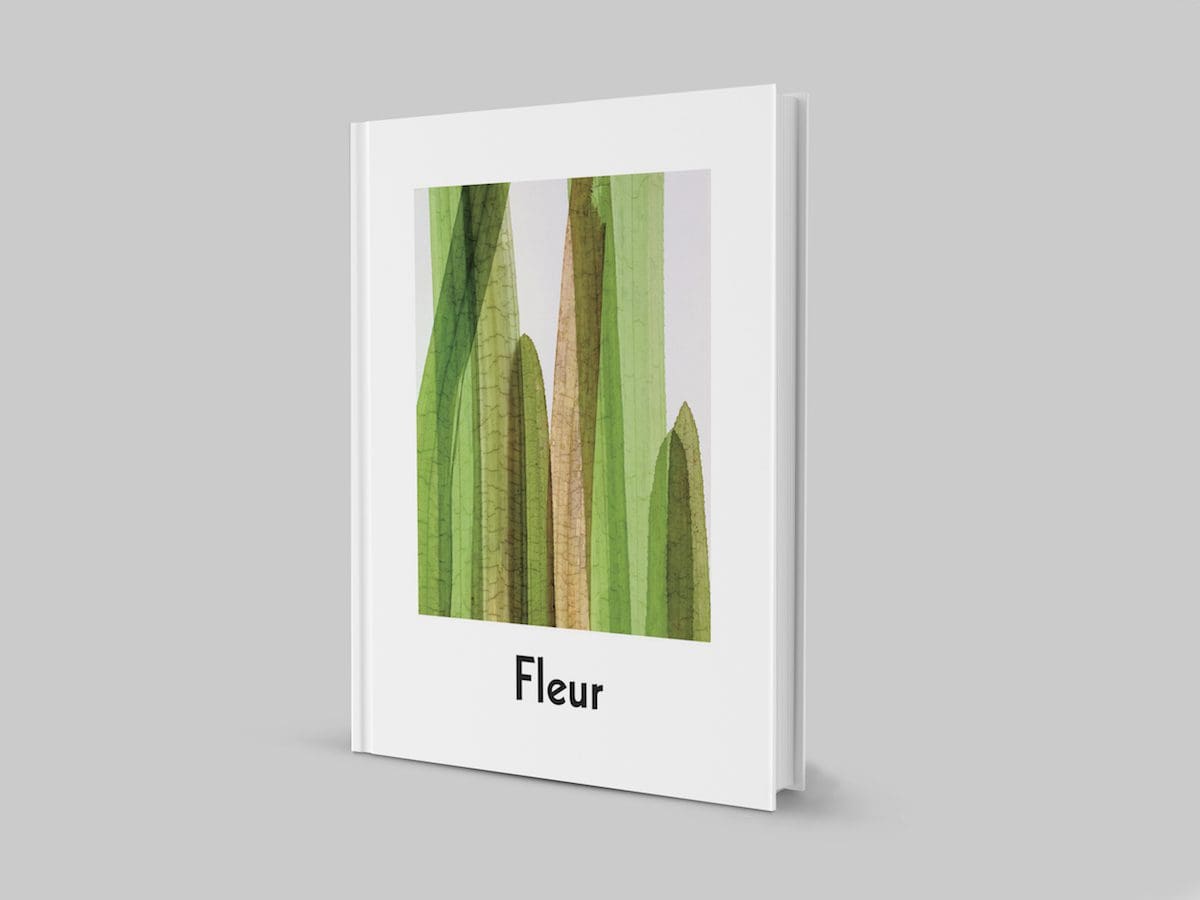

My monograph Fleur: Plant Portraits by Fleur Olby with a foreword by Wayne Ford, was published by FUEL Publishing in 2005, a combination of commissioned and personal work from ten years of floral still life. It was in the Tate Modern and The Photographers’ Gallery bookshops and distributed internationally with DAP and Thames and Hudson.

But after 2008 with two client insolvencies causing further problems after the financial crash, it took me a long time to find a way forward with my archives. The two commissions, Horsetail Equisetum for Gollifer Langston Architects and a textile collaboration with Woven Image in Australia were the archival commissions from that time that enabled me to move forward.

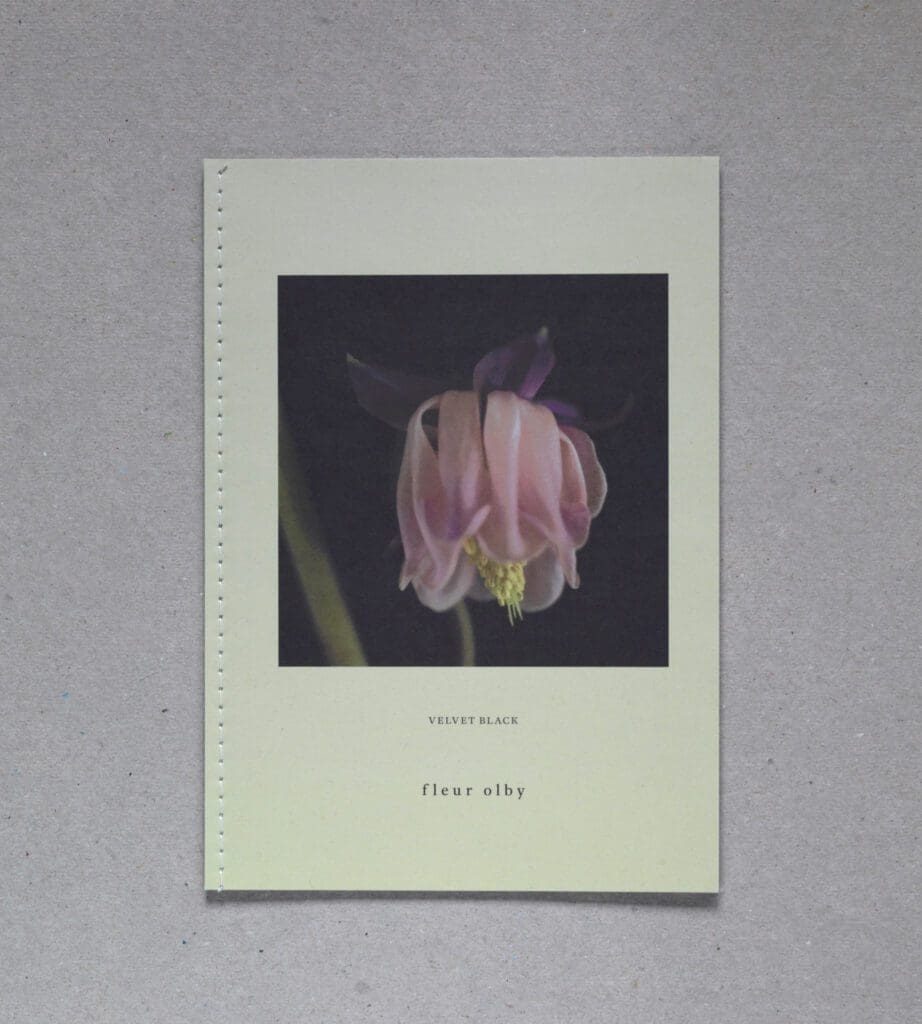

I had started a long-term project about the connection with Nature, Colour from Black. My Imprint has the first publication from these series, Velvet Black and limited edition prints that have exhibited at the Photography Gallery in the Museum of Gdansk and my solo show earlier this year at The Garden Museum, London. The A5 publication launched at Impressions Gallery Photobook Fair in Bradford and the A5 and A6 special edition are currently also at The Photographers’ Gallery bookshop in London. I aim to continue with self-publishing the series in small books and work in collaboration on the projects that evolve from them. Images from other series have also been shown in group shows in the UK and abroad.

Can you describe your process, and how your choice of film stocks, different formats and use of low light levels create the particular viewpoint you are interested in capturing?

The series artistic aim is to connect dreams and reality and through this work I have experimented with different mediums. It is less about the impact of a single image, my interest is in the pace and change of the narrative. The personal aim is to conserve plants and the elemental feeling of beauty in Nature. My commercial work was studio light, mostly shot on 5/4 Velvia and Provia film.

In my long-term series, the colour is subtle but fully saturated, in natural light. The low light started with the series Velvet Black as a present-day ode back to Victorian plant theatricals, collections and plants from a garden – the correlation between the transience of daylight and blooms.

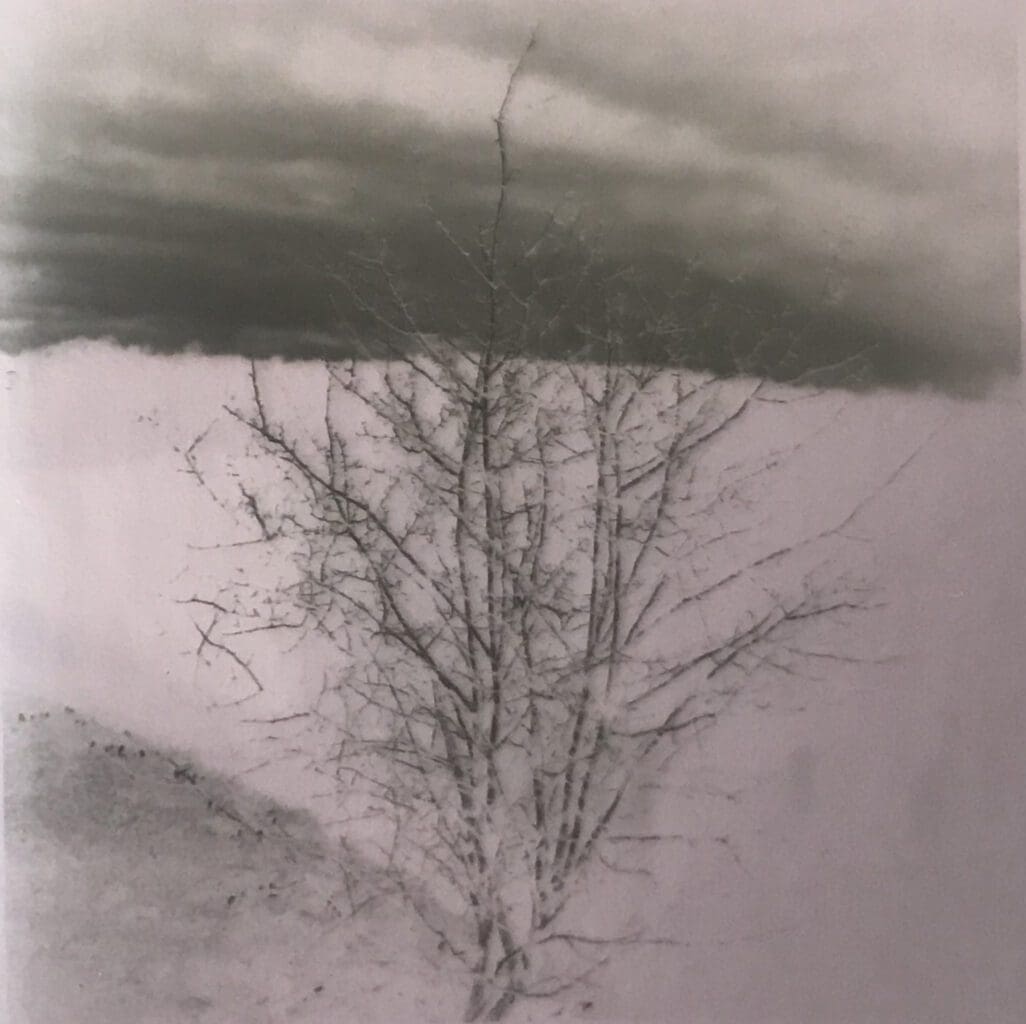

I was also experimenting with my iPhone as I was trying to capture the spontaneity of feeling from walking. My working process has evolved: It begins with walking and pictures that I revisit on medium format for a different kind of precision that allows long exposure. I am now mixing instant images and film from Black and white and colour. The series made at Hillside was the first time I combined the different mediums and shot Dusk, Dawn, Dusk in succession. I used Instax and my phone to find viewpoints from the paths. I remade some of the images on the Ipad to map out the plan.

Then I shot with a Polaroid camera in reasonable light and shot film and digital on medium format at Dusk and Dawn. The film was mostly Ilford, HP5, FP4 and XP2.

There is a quiet intensity to all of your work, a feeling of being tuned in to a different way of seeing the familiar. The fact that you work in series also gives a very strong narrative quality to your images. What would you like us to see in them?

Thank you, that means a lot to me! The quiet intensity was what I needed to reconnect with when I began to revisit childhood places that inspire me on the moors, on the hills, in the garden.

With the narratives about Nature, I wanted to slow down the viewing process and to question the feeling of Beauty through light and repetition within the series. In the book Velvet Black I use the smell of the ink, the texture of the paper and the folded pages to slow down the process in a similar way to a flower press. And the printed absorptance of the page makes the transient process of nature into a permanent object.

There is a distinct balance in your work between wild, elemental landscape and the intimacy and perfection of a single cut flower. What is the relationship between these two worlds for you?

I think this is the path I am trying to narrate between the perfect oak leaf from my childhood to the tree out on the hills.

When we asked you to come and take photographs at Hillside what were your first thoughts ? When you were here were there any particular observations you made about photographing a garden set in landscape?

It was great to hear from you both. I was excited about the thought of visiting Hillside. I remember our conversations about the work you were inviting artists to make and what aspects of the garden they were focusing on. But on arriving I couldn’t think how to divide it up into one particular interest and I knew I wanted to convey feeling.

I arrived between the storms of February, the quiet calm lull in the garden was breathtakingly beautiful. No-one was there until later today.

I started to walk – the paths led me everywhere. Enclosed and defined by the garden in and out of the landscape. I did not know this terrain, the feeling and scale are different, the quiet remains the same – the shape of the hill on the left is gentle and round, it stretches out into another at the front with incredible mature trees. The main garden is perched high up within the undulation of the hills. How will I capture this?

I felt I was intruding the serenity of the place, I stood amongst the plants’ skeletons taller than me and thanked them for remaining standing despite the storm – looked out at the echo of the trees beyond, walked down the hill towards them and looked back up to where I’d been standing – It is like a painting, brushstrokes of layered texture highlighted by the time of the year and the trees and hedges beyond it, darker shapes in repetition above. Light in colour as its ready to be cut for new planting and the two gates take me in and out of place and garden and into wonderment. I’m not sure I can express this.

Then there’s the bridge at the bottom of the stream with wrapped up plants on the edge that I could spend all day shooting, the vegetable garden! The artichokes! The Cavolo Nero – The two architectural stone troughs define the scale of the outdoor space and feel spiritual, a verbascum ode nearby reminds me of my Dad and makes me smile, the hedges, the orchards and the young woodland at the back. Flowers resiliently here and there touched me – intricate planting inspired me. I had to process a plan and start.

I wanted to try and capture this movement, the feelings from walking this dreamworld and its reality. I worked on different cameras in repetition in positive and negative to intensify the shapes and colour and black and white to intensify the feeling and pictorially play with resonance.

Do you feel that you learnt anything new from the time you spent photographing here?

It was immensely helpful to be invited to work like this, and I enjoyed the intensity of making the work. I made a new working process shooting 3 formats and running between captures to put the instant film to process inside and continue with the film outside. I made quite a lot of work in the time and it was the first time I shot constantly connecting dusk and dawn.

It enabled me to see how my work has progressed more clearly and how I can put it together because it was the perfect balance of how the garden and landscape coexist.

How was lockdown for you creatively?

Lockdown happened during my show at The Garden Museum.

I contributed to Quarantine Herbarium’s cyanotype project and the Trace Charity Print Sale which raised money for the charities Crisis and Refuge.

I listened more to the birds, watched the animals’ paths and felt exceptionally close to them and that continues. I was also busy shielding family, and I spent more time growing vegetables which I do as much as possible.

I stopped shooting and started to edit more.

What are you working on now and can you share any ideas you have for future projects?

I have had to revise my plans for this year, events I had committed to were cancelled. I am reworking everything and plan to bring the next series out in 2021.

The full edit of the photographs Fleur took can be seen on her website.

Interview: Huw Morgan | Portrait: Howard Sooley

All other photographs: Fleur Olby

Published 24 October 2020

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage