The Tenby daffodils are flaring on the banks that fall steeply into the ditch. Backlit by morning sun they are the purest of yellows, brilliant and bright and so very full of life. The tilted buds are already visible breaking their sheaths as the snowdrops dim and the primroses take over and begin their moment. The narcissus join them then, not to overshadow as you might think, but in a partnership of yellows, the colour of spring and new life.

Now considered a subspecies of our native daffodil, N. pseudonarcissus subsp. obvallaris is found locally near Tenby in Dyfed, South Wales, where they have a small range of natural distribution. Their cousin, N. pseudonarcissus, is variable, with a soft yellow trumpet and palest yellow petals, so a group registers quite differently and they have a softness that sits easily. Not so the Tenby daffodil which is brazen and to the point, being bright chrome yellow throughout. Though this might not be easy in a larger daffodil, the Tenby is no more than a foot tall and everything is perfectly proportioned and neat. Thus they weather the March storms and stand like a person with innate confidence that is happy in their own skin.

The crease in the land that we call the Ditch is far more than that. It is the divide between the ground that we garden and the rounded rise of the Tump that we look out upon and forms our backdrop to the east. The spring-fed rivulet that runs quickly down it is constant and gurgling, even in summer. The silvery slip of water was revealed when we cleared the brambles 10 years ago and fenced it on both sides so that this distinct habitat could become an environment of its own. We have been building upon the nature of this place ever since. Splitting the primroses that sit happy in the heavy, wet ground and stepping plants through it that are either closely related to the wild plants that thrive there or feel right and can cope with the competition.

The Ditch is a place that we garden lightly and the plan is to one day have it naturalised with bulbs that like the conditions here. Snowdrops and aconites to start the year and snakeshead fritillaries and camassia to follow. The Narcissus obvallaris are grouped loosely around a staggering of Cornus mas, which start to bloom when you can feel the winter easing.

So far the Tenbys have not started to seed, but I hope that our man-made imprint can be softened with seedlings that find where they want to be. This has begun already with the straight Narcissus pseudonarcissus, which I’ve been planting lower down the slopes and, in an echo of the ones we found higher up the valley, growing on little tumps that run alongside the stream where the hazel grows. They sit there with the young Dog’s Mercury as a marker of this ancient woodland and looking down on all they survey. The way they grow in the wild is a good measure for where they want to be when you find them their home. Cool, but not in the wet hollows and with a little shadow later to ease up the competition of the more thuggish grasses.

Having been stung a couple of times with narcissus orders that were incorrectly supplied, I started three years ago by potting up a hundred bulbs, two to a pot, as I needed to know that we were putting the real thing into this wild place. It was the year that Huw’s mother passed away and, as his family are from Swansea, it felt fitting to be planting them out just a fortnight after she died. The Tenbys start to bloom around St. David’s Day and, when the first yellow shows, we add another round of plants potted up the previous autumn. Midori and Shintaro from Tokachi Millennium Forest took part one year when they were here to stay on a ‘gardening holiday’ from snowbound Hokkaido, and it has now become something of a tradition to plant a number round about now to find the places in the ditch where we feel the light needs capturing.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 13 March 2021

Suddenly the violets are in bloom, an invisible cloak of perfume that hangs heavy by the milking barn. They are planted for exactly this moment, on the bank by the path, in the lea of the building and where the early spring sunshine unlocks their early blooms and bounty. The surprise, when walking into their orbit that first spring day makes you instantly breathe deep.

The handover from winter to spring started in the third week of February and in reaction to a week of hard freeze. The catkins on the hazel fell like streamers being shot from above at a party and the silken pussies on the willows gathered in number and glistened in light reflecting shoals. A windy few days, which saw the gales leaning heavily into the garden put paid to the snowdrops, but in a perfectly orchestrated handover, the primroses were there to replace them. One or two at first and, within just a couple of days, more than you could count and running away into the distance where over the years we have been splitting and dividing.

Although it comes with a little sadness to be clearing the garden, the push of the new has made way for change. Old stems now feeling tired for the contrast of fresh buds at their base and the expectation of spring applying a mounting pressure to move on and make way.

Each year since we planted the garden, the clearances have revealed a place that is slowly hunkering down and becoming itself. The layering I had planned for and that only comes with time. Pulling back the old growth and cutting it to the base is always a good time to look and see what has really been going on under the cover of a growing season. Asters that are on the verge of running riot where they have got the upper hand on their companion. The sanguisorba that this year will need dividing to prevent them from toppling mid-season.

The clarity of the clearance also reveals the interlopers. This year it is a running epilobium which has jumped from the nearby ditch with wind-blown seed. Growing away happily and out of sight it has set up home with a mother plant and she has begun to run. Ducking and diving and popping up a new and lustrous rosette like a mole throwing up hills. Fleets of arum seedlings have also made their way in through birds that have been resting up in the spent stems of winter and pooping. The parent plants, which now have a lusty presence in the garden hedge just a few strides away, have obviously been sizing up the ‘open’ ground of the garden. Beth Chatto warned me about the Arum italicum which had taken over her woodland garden. “It is a terrible weed.” she said, “Watch out for it!”. I have been and I will, each seedling carefully removed with a long-bladed trowel, being very careful not to leave the pea-sized corm at the base.

Pull away the old growth and you find the evidence of life that has been going on under cover. Scatterings of a specific stripy snail shell, smashed around a stone where the thrushes have made their makeshift anvils. Nests of mice and voles under the thatch of the ornamental grasses. You can imagine how cosy it must have been as you pull the old growth away to expose the evidence of their foraging. Neatly gnawed holly berries and what I’m thinking might be the dismantled seed heads of the Agastache nepetoides that I’d been looking forward to for their blackened winter pokers. They mysteriously vanished over the course of a week in the autumn.

As the garden grows and becomes its own ecosystem, every year demands a specific response to retain the desired balance. I made a start this year in January where I’ve been planting bulbs and early woodlanders in the shelter of the shrubs that are now casting their influence. The Cardamine quinquefolia are already showing green when most of their companions are sleeping. Running happily amongst the dense rosettes of foliage cast by the hellebores, they make perfect company if you cut the hellebore foliage in December when making way for the flowers. The cardamine will have done its feeding and be flowered and dormant again, their short life above ground stored in wiry rhizomes and done by the time the foliage takes its space back on the hellebore.

The big clear up at the turning point between winter and spring takes place in the cross over of February into March. We take three weekends usually with the middle weekend being with invited enthusiasts and many hands on deck. Not so this year, the year of things being less social and more distanced. So the clearance will happen over a month and take another week to work our way clockwise. From the top where the Allium ‘Summer Drummer’ is already etiolated with its early growth drawn up into last year’s skeletons. We will then pass around the outside where the pulmonarias are blooming in the sun and need to be liberated and enjoyed. Finally we will draw back in to the centre, the most complicated of the beds where the detail and fingerwork is intensified. It is a process of reveals and observations, decisions and actions. One leading to another and spring engaged with through the doing.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 7 March 2021

We’ve never had much luck with cauliflowers. With a reputation for being tricky customers, sensitive as they are to inconsistency during the growing cycle, they also generally require a very long growing season, thus making inconsistencies in cultivation far more likely. As the queen of vegetable growing, Joy Larkcom, succinctly states in our kitchen garden bible, Grow Your Own Vegetables, ‘The secret of success is steady growth, with plenty of moisture both at young plant stage and when maturing. Growth checks are caused by delayed transplanting, or spells of drought, resulting in deformed and small curds.’ Having had some unexpected success with the purple-headed ‘Sicilia Violetta’ two years ago, last year I was determined to break our dissatisfactory run once and for all and grow a harvest we could be proud of.

I had picked out two varieties, both from Real Seeds, ‘All The Year Round’ and ‘Autumn Giant’. The first because it promised the ease of successional sowings, and the second since it was reportedly ‘very reliable’. Both were sown in plugs on April 12th and were ready to plant out five weeks later in the middle of May. I looked after the young plants assiduously, watering them regularly and giving them a fortnightly liquid manure feed from mid-June as the plants started to grow away in earnest. Whether the feeding initiated it or not I can not be sure, but by early July it was apparent that all eight plants of ‘All The Year Round’ were on target to produce huge and beautiful, snow-white curds that would all be ready to harvest simultaneously in a matter of days. It was equally apparent that there was no way Dan and I were going to be able to eat all of them ourselves in the time available.

I chose my day carefully, reorganised the freezer, cleared the decks in the outside kitchen and assembled the equipment required for a mammoth batch of blanching. Cauliflower plants are huge, and it took some sawing and wrestling to take them all down, but eventually my catch was landed and Dan took my picture standing over them, inordinately proud. A large pasta pan with a colander insert makes blanching an easy affair, and as each batch went in I would set the timer for 3 minutes and return to preparing the next in line, removing the leaves and slicing each floret in two. Despite my apprehension of a neverending mountain of caulis the whole process of harvesting, preparing, blanching and bagging up seven of them for the freezer took around three hours. This really doesn’t seem a bad investment for the number of prep free meals they have provided this winter.

Dan posted his pictures of me on Instagram and that evening I got a message from Errol Fernandes. Errol is a Senior Gardener at Kenwood House in Hampstead and through his connection to Great Dixter we have come to know each other a little on social media, but have never met. Errol directed me to a post of his which gave his own recipe for blackened cauliflower inspired by his Goan mum’s home cooking, in the hope it might help us get through our cauliflower glut.

Knowing that we live in deepest, darkest Somerset Errol offered to send me some of the harder to come by ingredients – namely the back salt, powdered lime and mango powder. I have used dried lime and mango powder before, but never the black salt. Errol warned me, ‘It smells like bad eggs, but don’t be put off! It’s essential for the dish.’ When the little cellophane packets with hand-written labels arrived a few days later the distinctive sulphurous smell instantly transported me back to the Diwana Bhel Poori House on Drummond Street behind Euston station. When I was living in Camden in my mid 20’s I used to eat there on a weekly basis with my friends Simon and John Paul. The crisp-shelled poori, served with potatoes and chick peas and an appetising chutney that I now understood was flavoured with black salt.

Black salt (also known as kala namak) comes from volcanic salt mines in the Himalaya, and has been used in Ayurvedic medicine for centuries for its cleansing, detoxifying and digestive properties. Its pungent smell acts in a similar way to asafoetida, adding a deep, hard-to-pin-down umami richness which makes it incredibly more-ish. The powdered dried lime, mango powder, lime juice and turmeric combine to produce a deliciously astringent flavour which makes this a perfect dish to greet the changing season and wake up our slumbering taste buds and livers.

Each time I have made this dish I have taken the little cellophane packets of black salt and lime powder that Errol sent out of the spice cupboard and each time I have been reminded of his kindness at that time. We had just come out of the first lockdown and everyone was feeling raw, apprehensive and yet keen to connect. As Errol wrote to me when I asked him if I could share this recipe today, ‘I love sharing my food/culture, and I love learning about other people’s. Food is a wonderful way of connecting…’ So, as we look forward, hopefully, to a summer of renewed connections, it makes me happy to be able to share that connection with you.

1 cauliflower (around 1kg)

1 tablespoon coriander seed

1 teaspoon mango powder

1 teaspoon lime powder

1 teaspoon black mustard seed

1 teaspoon turmeric powder

1 teaspoon salt flakes

½ teaspoon cumin seed

¼ teaspoon garam masala

¼ teaspoon Kashmiri chilli powder

¼ teaspoon asafoetida

¼ teaspoon Himalayan black salt

½ large green chilli, coarsely chopped

1 large clove garlic, coarsely chopped

8 curry leaves

Juice of half a lime

2 teaspoons cider vinegar

2 tablespoons rapeseed or other unflavoured oil

Separate the cauliflower into florets and cut these in half or in quarters depending on size. Cut the core and stalk a little more thinly. Include the young tender leaves too. You want bite size pieces that all will cook evenly. Put it all into a glass or ceramic bowl.

Put all of the other ingredients into a mortar and crush slowly and gently to make a coarse sauce. You want the garlic and chilli to be bruised and broken, but for the whole spices to mostly retain their form.

Spoon all but one tablespoon of the marinade over the cauliflower and mix thoroughly. I find it is quickest and most thorough to do this with your hands, but wear gloves if you don’t want the turmeric to turn your hands yellow! Cover and leave to marinade for at least an hour.

Pre-heat an overhead grill to hot. Arrange the cauliflower pieces in a single layer on a baking sheet and put under the grill for 20 to 25 minutes. Turn the pieces every now and then until all are cooked and charred in places.

Spoon the remaining marinade over the cauliflower with a squeeze more lime juice. Garnish with fresh coriander and more finely sliced green chilli and eat piping hot.

Serves 4 as a main side dish or 6 as part of a mixed plate meal.

Recipe: Errol Fernandes | Words & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 27 February 2021

Against the odds, the delicate Crocus tommasinianus ‘Albus’ spear the turf on the bank in front of the house. When you first become aware of their presence earlier in the month it is easy to mistake their pale tapers for the light reflecting off blades of grass, but suddenly and all at once they are free. Standing tall enough above the sward to shiver in the slightest of breezes and opening wide in a sunny interlude to reveal orange stamens, yellowed throats and nectar for the early bees.

I first grew Crocus tommasinianus in the Peckham garden and learned to love it there for being the superior cousin to the ‘Dutch’ Crocus vernus which stud front lawns in spring like spilled tins of Quality Street. I did not know it then, but I had been supplied with the true species, which has the palest silvery-lilac reverse to the petals with the colour held within. I have since repeated my orders, again and again and from different places, only to find I have planted a thousand ‘Ruby Giant’ here or two thousand ‘Whitewell Purple’ there. These darker selections are often mis-supplied and sit less lightly for their weight of saturated colour.

Just up the lane and making the point that they are happy there, the true form has taken over our neighbours’ garden. The sisters that live there are natural gardeners and have been tending theirs now for decades. Without competition the crocus have seeded freely, to the point of flooding the open ground of their borders, seeding into the crowns of all the plants and seizing every niche between paving stones. The garden is free and joyous and Josie and Rachel never see their occupancy as a problem.

We have struck up a friendship and Rachel has generously allowed me to dig them in-the-green immediately after flowering so that I do not have to depend upon the vagaries of the bulb suppliers. I am going to keep them out of the beds here, however, as I want to work in the garden just as they come into leaf when I’m preparing the garden for spring. The sunny banks at the back of the house are where I am hoping they will naturalise. The free-draining slope there is ideal, because they like dry ground when they are dormant and the sunshine ensures that their flowers, which are light sensitive, open to reveal their interiors. When they do, you feel your heart lift and the long dark winter retreat.

I can already see from their behaviour in the grass under the young crab apples that they will not seed as freely as they have in the open ground of Josie and Rachel’s garden. Though happy in grass, the lushness of our meadows is probably too much for the young seedlings to take a hold. I hope in time, and once the grass thins as the crab apples assert themselves, that they will take to a lighter sward and begin to make the place their own. This is worth waiting for and every year I am adding a few more with Narcissus jonquilla and Anemone blanda to follow after their early blaze is over.

Shipton Bulbs stock a number of special selections that are subtler than the named varieties above. The rosy Crocus tommasinianus ‘Roseus’ (main image) and C. t. ‘Pictus’ which looks as though the tips of the petals have been dipped in ink. The white form, Crocus tommasinianus ‘Albus’, is very choice and, as they do not come as cheap, I ordered a couple of handfuls and gave them their own place on on the bank at the front of the house in the hope that they will not cross with the others at the back. The position here is exposed to our winds that whip across the open ground, but they stand bravely and mark the shift in the season with the snowdrops and the promise of what lies just around the corner.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 20 February 2021

A chill easterly wind has held us firmly in its grip, whistling around the house and freezing the puddles and the muddy gateways. The pots of early bulbs have frozen solid even up by the house, their growth suspended for now. I look out over a landscape that feels right for February. A crunch underfoot and the mixed feeling of knowing this is as it should be, but hoping that the bay tree will survive the scorch it has suffered from being left to fend for itself in previous years. Wrapped in advance of the freeze last week, I’m feeling hopeful.

This is our last week of winter work. I drew up a list in late November that we started as soon as the foliage was down on the trees. Weekly tasks beyond the garden that take us out into the rougher places where energies are only applied when the garden itself is resting.

Ten years on and we have begun thinning in the blossom wood to allow the young saplings there the room to become trees. The fast growing hawthorn and Cornus stolonifera, have served their purpose as nurse trees. The microclimate they have provided for the slower growing oaks and Sorbus torminalis has allowed for the canopies to meet and the ground to be protected. Returning there in this period of dormancy we spend a couple of days making gentle clearances. Felled wood is pulled out and logged and the brash is made into brush piles where it slowly moulders back to earth whilst providing shelter for the critters. After snow you can see their footprints going back and forth from these protected places so that we now feel like intruders in the wood. We will revisit for the blossom, but as soon as the nettles that have claimed the open ground have sprung we will leave this place in peace for the summer.

Every year I make it my mission to return trees to the land. At first it was to complement the ash, which is our dominant tree, but now it is to replace them as we are beginning to see the brutal effects of the Ash Die Back that is sweeping the country. To keep the fields that we are retaining for meadow open, new trees have been worked into gaps in the hedges – English lime and field maple – whilst oaks are placed by the gates as marker trees. This year we planted thirty oaks along an open stretch of hedge to extend the still air that is usually harboured to one side of the hedge and provides a hunting grounds for owls and bats. The higher canopy will eventually harbour an invisible highway of stillness that extends their territory and also a future roost for the birds that currently pass through the open landscape. Though we will never see the trees mature, it is a fine feeling to imagine these places and to help begin their futures.

Working slowly inwards, the winter works this year have included the restoration of a hedge below the milking barn that was mostly taken over by elder. The elder is the bully in a hedge, growing faster and muscling out its neighbours, so the plan has not been to eliminate the elder but diminish its numbers where it has become dominant. Three years ago, in preparation for this moment, I sowed hawthorn and guelder rose, wild privet, eglantine rose and spindle from our own saved seed. These youngsters are now ready to be planted, so the old hedge was felled to the base to allow us the chance to pull out the farm detritus that was put there to gap up the holes. Old bedsteads, buckled railings and a chain harrow in this instance. The elder roots will be grubbed out and the remaining hawthorn allowed to re-shoot. We stacked the prunings as a dead hedge to one side where it will be allowed to rot and in the meantime protect the young hedglings that plug the gaps. A new stock-proof fence to the open side will keep them secure until they are grown and established.

With time finally playing into our hands through not splitting our life with London, the orchard was pruned for the first time properly. I had always intended the trees to be grown to full size and not pruned for production, but we still need to plan for health and good structure. Any diseased wood was taken away first, some trees being more prone to canker than others. Crossing branches were targeted next and then the centre of the trees gently opened to allow free air movement. My grandfather said to maintain their health you should be able to throw your cap through an apple tree. Our trees will be more relaxed than this, but it is good to see, now that they are a decade old, the varieties each assuming their own character. You only know this from growing something for yourself and the thought often has me pondering that you really need another lifetime of learning.

This winter I’ve also had time to revisit the espaliered pears, which are now showing me where I have been too busy to make the right moves in training the limbs in past summers. On one such example, I had to make do with limbs trained from a lower tier where I had simply missed the boat because I was travelling too much for work. You need to plan ahead with trained fruit as the years become mapped in the limbs. A restoration prune, to remove some wood to promote the growth where I need it, should hopefully address time lived too fast and be more worthy of my Wisley training. A gardener’s training that has made me feel a little guilty every time I see my neglect advertised by the poorly trained branches.

Onward, in readiness for beginning the big cut back in the garden next week, we are clearing the compost heap as the final job on the winter works list. The clearances from last year are now composted and good for mulching and soil improvement. One cycle completed, the profits from the last one in barrows full of goodness and the next about to begin.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 13 February 2021

Last week we passed the half way point between the winter solstice and the spring equinox; the Gaelic celebration of Imbolc. Here in the garden there is a notable shift from slumber. Bright rosettes amongst the leaf litter, looking determined and suddenly visible. Newly green amongst the darkness of foliage from last year, which is daily being pulled to earth by the earthworms and mouldering. The cycle making way and the old providing for the new as the nights become shorter.

In the garden, it was the witch hazel which were the first to stir. I grew them in pots when we were living in Peckham and were pushed for space and needy for more. They were brought up close to the house where their winter filaments could be given close and regular examination. They grew surprisingly well considering their confinement, to the point of outgrowing their summer holding ground in the shadows at the end. I passed them on as they outgrew us. ‘Jelena’ was big enough to warrant the hire of a white van and driver to take it to Nigel Slater in his north London garden. A number went to clients and the remainder came with us in an ark of the best plants to live with us here.

Our sunny hillside with its desiccating breeze does not provide the ideal conditions for hamamelis. In an ideal world they would go down in the hollows, where the air is still and the cool shadows finger from the wood on the other side of the stream. Although they are modest and do bear a likeness to hazel in summer, their winter value is bright and otherworldly. Too bright and too ornamental to sit in the company of natives.

As a highlight of these dark months, the witch hazels are worthy of the pockets of shelter up in the garden. Hamamelis x intermedia ‘Gingerbread’ claims one such position alongside the old milking barn, where the west-facing aspect protects it from the sun for more than half the day when it is at its height. On a still day a delicious, zesty perfume describes a definable place that you encounter as you move alongside the barn. It makes your mouth water. The colour of ‘Gingerbread’ is well named. It is hot and spicy, but dims after a couple of days perfuming the mantlepiece.

The plant must be about fifteen years old, given its time in London and the early years here still confined to its pot. Though slow to settle in, the limbs now reach out widely and provide me with a little microclimate. Its branches offering a shadowy place beneath for lime green hellebores and paris and a climbing frame for scarlet Tropaeolum speciosum, which covers for the witch hazel’s modesty come the summer.

The willows come once the witch hazel are already in bloom, their neatly fitting sheaths thrown aside as the pussies begin to swell. Salix daphnoides ‘Aglaia’ with dark mahogany stems and silver-white catkins sits a walk away as an eyecatcher down in the ditch. Closer in Salix gracilistyla, acts as guardian to either side of the lower garden gate. Not so commonly available as the black form, S. gracilistyla ‘Melanostachys’, or the pink-pussied S. g. ‘Mount Aso’, I love the straight species for the delicacy of silvery-grey. Like the fur of a rabbit, it is impossible not to touch as you move to and fro and I have let the branches reach in from either side to encourage this interaction. As the flowers go over, the bushes will be hard pruned to a framework in early April to keep the plants within bounds so you can see over them and still have the view.

Just a week after the winter mid-way we find ourselves at peak snowdrop. Those in the warmest positions where they bask in winter sunshine have been out already for a fortnight, but right now is the week of the majority, at their most pristine and poised. What the Japanese call shun, the moment when a plant or crop is full of its vital and optimum energy.

I have fallen under the spell, for the snowdrop’s solitary presence is a tonic when you are pining for life. Their ability to draw you out into the winter and make it a place that is finer for their presence is why, perhaps, when you do find yourself spellbound, you begin to want for more. That is another story altogether. One which I will share with you another year when I feel I know more, but suffice to say I have begun a collection of specials. All three here (each named after characters from Greek mythology) are readily available for being reliably good plants and you can buy them easily enough in-the-green, as bare root bulbs from Beth Chatto’s for planting out now. ‘Galatea’ was first given to me by our friend Tania. The ‘goddess of calm seas’ is a fine reference, but the long pedicel suspends the flower in the arc of a fishing rod, so if there is a breeze, they are wonderfully mobile. In the warmth or on a bright day, they fling their petals back in a joyous movement to expose their skirts to the bees.

Though the doubles tend to last longer in flower, they are not always my favourites. The bees favour them less because they are harder to pollinate and the simplicity of the flower can often be lost in frilled petticoats. Not these two, which both have an interior that is beautifully tailored. ‘Hippolyta’, daughter of the Queen of the Amazons, is the shorter and more upright of the two with a fullness and roundness to the flower which is distinctive from a distance. ‘Dionysus’ has both poise and height, though it is good to plant the doubles on a slope so that you can admire their undergarments. Named after the god of wine (and ritual madness) I am happy to be swept along in a little obsession and midwinter mania.

Words: Dan Pearson | Flowers & Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 6 February 2021

Life has begun to stir, the snowdrops suddenly visible and lighting the gloom. Over the last ten years I have been adding to a ribbon that is designed to draw us out into the landscape. It starts in the hedges close to the house and skips down the ditch in a stop-start rhythm where I have found the places that they like to be. Not too wet and with just enough shadow to keep the grass down once they have come into leaf and do their bulking. They reappear then down by the stream to run its length and ensure we walk our stretch whilst we can still get to the water in winter. The gesture demands generosity and commitment to adding to the trail, like a conversation you come back to, but is never really done.

We need to think expansively beyond the curtilage of the garden, where the land takes over and we could never nor want to control all that we see. Although the touch by necessity needs to be light in these wilder places, it should also feel generous. Not in a conspicuous way, but right because you have found a niche and then followed it. The big moves always start with a small one. Finding the place that a plant likes to be and understanding why and then going with it.

Working at scale in these wilder places demands both patience and persistence. Neither feel forced or hard won when the mother plants begin to seed. The primrose splits from five years ago came from a colony that was hiding amongst a cage of brambles. We fenced the ditch to keep out the livestock, cut away the brambles and the primroses proliferated on the hummocky slopes where each had its little microclimate. The splits – taken early in April not long after the primroses had peaked – were found a similar position and, where we hit the sweet spot, they are showing their happiness there in seedlings. The seedlings slowly erase your hand. The regular rhythm you try to avoid when planting, but cannot help but read when you look back on what you have done. The seedlings skip a beat, their seed taken to a new place by ants. The ones that come through feel right for having found their own place.

By its very nature my role as the ‘gardener’ of these natural processes cannot help but want for a little more. So where splits have proved to be too slow – the mother plants taking time to bulk – I have taken to collecting seed. This is ripe in June, but you have to watch carefully then as the plants are often consumed in the shadow of summer vegetation. The seed is best sown fresh or it begins to enter a period of dormancy that is hard to break. Fresh seed germinates erratically, some in the late summer and over autumn, but the majority in the spring after it has had time for the frost to do its work.

I sow three or four plug trays each year (between 300-400 plants) casting the seed over the tray and then top-dressing with sharp grit to protect it. Sowing annually means that I have a relay of seedlings on the go. Seedlings are left in the trays for 18 months and planted out just about now, when there is time for their early growth to get ahead of the competition. This year the seedlings are going into the steep banks up behind the house, where the sheep have opened up the ground with heavy grazing and poaching. The slope is south-facing and primroses love to bask in early sunshine. Here the bees find them early too. The summer cover of the grassland that rises up around them will keep them in the shade they like later.

Also in mass production and destined for the wilder places are some locally sourced bluebells grown from seed. This is not bluebell country, their niche here being on the heaviest clay in the woods and not where it is too rich and competitive. I have been studying our ground to find the place where I imagine they might thrive, even just in pockets so that we have some pools of blue in the coppice.

Then there are the bulbs that are too expensive to buy in bulk and that I hanker for en masse. Camassia leichtlinii originally bought as ‘Amethyst Strain’ from Avon Bulbs and now renamed Avon Stellar Hybrids, are destined for the ditch. Well-named for their colour range of mauves and lavenders, their propensity to rampant seeding in the open ground of the garden will be mediated by the competition of grass. Tulipa sprengeri (at a prohibitive £5 a bulb) comes easily from seed if you are prepared to wait, as does the pale-flowered form of the native early winter aconite, Eranthis hyemalis ‘Schwefelglanz’. I plan for sheets of this butter-yellow form one day, in the places that are too damp for the snowdrops, but on the same trail and flowering with them in January. Though the wait is usually five years to flower for most of the bulbs, the beauty of sowing every year means that there is always a tray finishing the relay and ready to join the land of plenty.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 30 January 2021

With the vegetable garden either too frosty or wet to work I finally got round to sorting out my boxes of vegetable seed this week, with a view to being as organised as possible for the coming season. Yesterday was the last day of the fourth annual Seed Week, an initiative started in 2017 by The Gaia Foundation, which is intended to encourage British gardeners and growers to buy seed from local, organic and small scale producers. The aim, to establish seed sovereignty in the UK and Ireland by increasing the number and diversity of locally produced crops, since these are culturally adapted to local growing conditions and so are more resilient than seed produced on an industrial scale available from the larger suppliers. The majority of commercially available seed are also F1 hybrids, which are sterile and so require you to buy new seed year on year as opposed to saving your own open pollinated seed.

I must admit to having always bought our vegetable seed to date, albeit from smaller, independent producers including The Real Seed Company, Tamar Organics and Brown Envelope Seeds. However, last year the pandemic caused a rush on seed from new, locked down gardeners and the smaller suppliers quickly found themselves unable to keep up with demand. If you have tried ordering seed yourself in the past couple of weeks you will have found that, once again, the smaller producers (those mentioned above included) have had to pause sales on their websites due to overwhelming demand. Add to this the new import regulations imposed following Brexit, and we suddenly find ourselves in a position where European-raised onion sets, seed potatoes and seed are either not getting through customs or suppliers have decided it is too much hassle to bother shipping here. This makes it more important than ever to relearn the old ways of seed-saving so that we can become more self-sufficient.

Many of our neighbours found themselves in the same position last March and so we created a local gardeners’ Whatsapp group to let each other know what surplus seeds we had and, once the growing season had started, when we had excess plants to share. We discovered that there were a number of young inexperienced gardeners locally who were keen to try growing their own, and it felt good to be able to give them a head start with our well-grown plants which might otherwise have ended up on the compost heap. As the season progressed messages pinged back and forth across the valley and when we were out walking we would spot little trays of seedlings and plug plants left by gates wrapped in damp newspaper, waiting to be collected to go into somebody’s vegetable patch. The cabbages, kales, tomatoes and beans we couldn’t gift to neighbours were left by our front gate with a ‘Please Help Yourself’ sign, and would be gone by evening. There was something very connective about this, despite the distance we all had to keep and the clandestine nature of the exchanges. A way of binding our little community together at a time when we were all reeling from the isolation of our first lockdown.

For the first time last summer, and with an eye on the likelihood of continuing supply problems, I started to collect seed from our own crops. As a novice I began primarily with the herbs, which don’t cross pollinate, and so now have my own seed of parsley, coriander, dill and chervil for this year’s sowings. There is also a pot of mixed broad bean seeds saved from the oldest pods before they were thrown on the compost heap, and which I will be sowing in a few weeks. Although they may have cross pollinated, since we always grow a couple of varieties, this is not necessarily a problem if you are just growing for yourself, although any plants that don’t come up looking strong and healthy should be discarded. I am planning on getting seed of our own beetroot this year (which is a little more involved as they will cross pollinate with other varieties and chard, so the flowering stalks must be isolated) and lettuces, which tend not to cross and so are easier to manage.

Last spring we had a very dark-leaved lettuce come up in the main garden from seed that had made its way from the compost heap. This looked to be ‘Really Red Deer Tongue’, which we had grown the previous year. Dan thought the foliage was such a good colour with the Salvia patens that it was allowed to flower, and we are now waiting to see if a rash of dark seedlings appears when the weather warms. Some will be kept in place and others transplanted to the kitchen garden when big enough. I am also keen to try keeping our own pumpkin seed this year, which will involve isolating individual flowers and hand pollinating them before sealing them with string to prevent insect pollination.

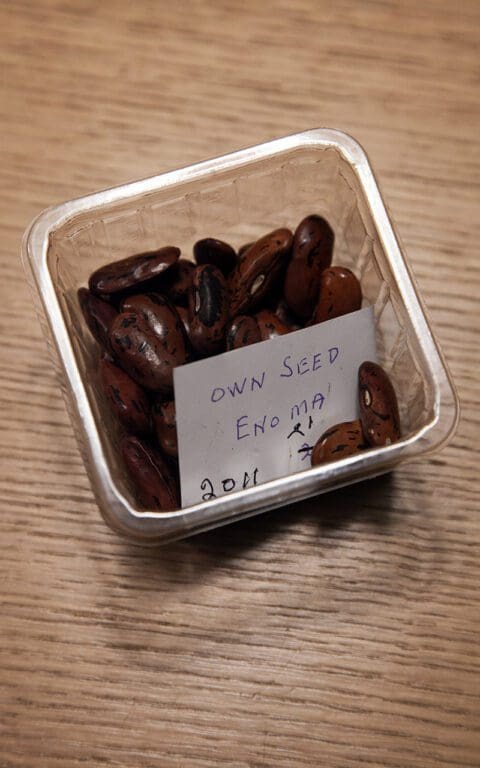

When sorting through my seed boxes a few weeks ago I turned up a small container of seed of the runner bean ‘Enorma’ collected by my great aunt Megan in 2011. Megan had been a Land Girl during the Second World War and was the most impressive kitchen gardener I have ever known. The long and steep, upwardly-sloping garden behind her house in Swansea was entirely given over to vegetables and fruit. She was completely self-sufficient in what she needed. Whenever you paid her a visit the house would be deserted and she would be in the garden come rain or shine, unless, of course, it was Sunday.

The last time I saw her at home – just a year before she became too frail, at the age of 96, to remain there – I walked up the three sets of precipitous, narrow brick steps to the garden to find her. I couldn’t see her anywhere so, in a momentary panic and picturing a senior accident, called out her name. There was a sudden movement at the periphery of my vision and Megan stood bolt upright, having been doubled over the trench she had just dug and into which she was carefully placing cabbage plants. “Just a sec!’ she shouted in her mercurial, high-pitched voice that was always on the brink of a giggle, and finished planting the row. She walked towards me, brushing the soil off her hands onto the brown checked housecoat she wore to garden in. “Well.’ she said. ‘What a lovely surprise! Do you want some tomatoes?’ Although she couldn’t stand to eat them, Megan had a greenhouse full of them, because she thought they looked so beautiful and she enjoyed giving them away to neighbours and friends. Needless to say she was green-fingered and I think a big part of the pleasure for her was knowing that she could grow them so well. She picked me a brown paper bag full and, as we left the greenhouse, I complemented her on her towering runner beans. ‘Oh, you can have some seed of those. ‘Enoma’,’ she said, missing out the ‘r’ and went to rummage in the shed for a moment.

This year, almost eight years after Megan died at the age of 98, I intend to plant her home-collected seed. A way of connecting me to the Welsh family that has gradually dwindled over the years and, perhaps, some of Megan’s skill and stamina will rub off on me along the way. Saving and sharing creates these connections between family, friends and strangers. It feels like nothing is quite as important as that right now.

The Real Seed Company give very clear advice on seed saving in two booklets available to download for free from their website here.

Words & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 23 January 2021

I first grew the stinking hellebore as a child on thin acidic sand in the shadowy stillness of woodland. We were surrounded on all sides and the woods were always on the advance to the point that, when we moved there in the mid 1970s, the vegetation was pressing against the windows. Our acre was a long-forgotten garden and we made clearings and pushed back against the brambles and the saplings as we unpicked what had once been there before.

The Helleborus foetidus was one of the plants that thrived for me there as a young gardener. My first plant was ordered from Beth Chatto and I watched its every move. The first year’s reach to establish its long-fingered greenery and the wait for the second for it to throw its mass of pale jade flower. The bladdery seedpods that followed in early summer and, the following spring, the rain of seedlings and the places that they preferred to be. Being easy in our setting, they taught me that, if you find the right place for a plant, it will sing for you. I can see those plants in my mind’s eye now. Quietly architectural, poised yet slightly melancholy, but holding so much promise when the leaves on the trees were down.

With my eyes newly opened and hungry for life in the winter I began to see it everywhere both in the wild and sitting happily in a garden setting. On the thin chalky soil of the South Downs I found it running through ancient woodland with lustrous hart’s tongue ferns, dog’s mercury and, later, bluebells. This was its territory according to the books, but one that couldn’t be more different from the rhododendron country we lived in just a short cycle ride away. I saw it then pushing onto a verge from a hedge and happy in sunshine where it was escaping a garden. Just a stone’s throw away the parent plant sat contentedly against the base of a bright flinty wall to challenge my feeling that I already knew this plant. Of course, I didn’t know from just growing it once that it is a plant that is happy to compromise if it likes you.

I have not grown Helleborus foetidus for myself again until fairly recently, living vicariously in the interim years through my clients’ gardens and conducting an erratic relationship, like you do with faraway friends. You have to fill in the gaps of influence when you see a plant, or indeed a friend from only time to time, but I have learned through time about its longevity. If the conditions are too good, it will live fast and move on after a handful of years. If you give it too much direct competition and immediate shadow it will dwindle and if you grow it hard, with plenty of light, be it a cool north light or the brightness of an open position, it will provide you with the most handsome growth. Handsome and all-year-round is what Helleborus foetidus does best.

The Lenten roses (Helleborus hybridus) are ultimately longer-lived and better adapted to a long distance relationship or the vagaries of their custodian’s gardening knowledge. So, the steadfast Helleborus hybridus were favoured in the Peckham garden where I didn’t have room for both. The Lenten Roses came from Peckham to here and until recently I hadn’t thought about rekindling my acquaintance with the stinking hellebore, because we are as exposed and open to sun as I was huddled in trees as a teenager. But just down the hill in a farmer’s garden, there is a colony growing contentedly where his intolerance of anything but grass has pushed them into a rugged bank that is too steep to mow. Seeing them happily flowering in the bright open sunshine amongst primroses reminded me it was time to live with them again.

I have put them in two places here, one in more shadow, amongst the rangy limbs of the black-catkinned Salix gracilistyla ‘Melanostachys’ and another group against the potting shed where the ground is dry and free draining and there is plenty of light under a lofty holly. They face east here and receive a blast of morning sunshine, so they have grown stockily amongst Butcher’s Broom (Ruscus aculeatus) and Cyclamen coum. Their leaves are also more metallic and light resistant than those growing in the shade of the shrubby willow. The two groups couldn’t be more different but they are coming into bloom together.

The plants take a year to get up the strength they need to throw their prodigious flowering head. This is held aloft and above the ruff of leafage beneath them. As they mature they branch again and again so that there are tens or even hundred at their zenith in March . The first opened here in the first week of the new year and the unravelling as one joins another is good to mark the passing of wintery time. The flowers are known for being slightly warmer when they are producing pollen and make a good early plant for pollinators. They will produce plentiful amounts of seed if you let them, but I prefer to leave just one limb to seed in a group and cut the rest to the base to save energy once you begin to see the plant has peaked in the middle of March or a little later. You will know when it is time as your focus goes to other spring flowers, which by this time are fresher.

One limb saved will rain all the seed you need for youngsters. All the remaining energy goes into the new growth, which comes from the base to mound architecturally over the summer. Though there is a fine, scented form called ‘Miss Jekyll’, the stink in the stinking hellebore comes from the foliage when crushed. It is when you are cutting this old growth away that you first encounter the beefy smell that you instinctively know will not be good for you. All parts of the plant are toxic if eaten and cause violent vomiting and delirium, sometimes death. Interestingly, in times past they were used, in miniscule quantity, to treat worms. Note, however, that the 18th Century herbalist Gilbert White called this ‘cure’: “a violent remedy … to be administered with caution”.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 15 January 2021

A stillness descends on the garden in January. Greenery pulled back to resting buds and all that is necessary to sustain the winter. It used to be that I wanted these weeks to be short, to be reunited with growth again, but increasingly this time feels precious for the opportunity to look at the bones. Quietened and slowed by the season and with all laid bare to see.

The weeks ahead are rarely a downtime and we are seldom plunged into a winter that makes the garden unworkable. Our snow lasts for no more than a few days and frost rarely stays in the ground for long. Winter here is a time for doing, readying and making changes. To be lost in actions and practicalities, with a mind’s eye on the spring. At least, this is how I see it and, at the beginning of January, I make a list of winter work that will take us through to the middle of February. The moment the snowdrops are in full swing, letting me know that the garden will also be stirring. In time to be ready to wade into the beds to remove the remains of the last season and free the resting buds to the air and the lengthening days.

The winter tasks begin with pruning and initiating order now that the leaves are down. When I started my formal training in the 1980’s we began the pruning at leaf drop, to work on the hardiest woodies first and to save the least hardy until the tail end of winter. So apples and pears and wall-trained fruits and climbers were the first point of focus. We paced ourselves and worked towards the roses, leaving them until the end of February to avoid making cuts that could then be burned by a freeze. I remember the winters then being harder and rose wood blackened from cuts made too early, but I have brought this work forward here in Somerset. In the ten years we have been here, we have never had a winter that has damaged the wood and the time I make up early in the year allows time for detailed work before winter tips in to spring. Mulching the parts of the gardens where there are bulbs that are yet to push through and splitting the perennials that stir early in March.

The winter work takes us out into the landscape with tree planting and hedge work and this is a good place to be to retain a clear overview and look back upon the garden. This year, with the help of John, who’s been helping us in the garden since April, we cleared the banks under the hazel at the top of the ditch where the snowdrops were already beginning to nose through the ground in December. They seem to appear earlier every year and I’d made plans to fell a mature hazel that we’d allowed to grow out from a previously broken hedge. There are just a handful of established hazel on the land, but the sixty or so youngsters I’ve planted to make a new coppice should be ready for harvesting by the time we have coppiced the elders.

Hazel responds well to coppicing on an eight to ten year cycle, sending up a fleet of fine young rods that thicken enough to harvest for wood and poles and branch at their reach to make a delicate weave for pea sticks. Wood cut in the first part of the winter retains a pliability that it loses the later it is cut, so the trigger of the snowdrops was useful in setting the winter work into motion in the last fortnight of December.

The old coppices I grew up with on the South Downs were well worked land and some of the oldest trees were possibly as much as a thousand years old with the middles of their ancient stools rotted away and the original plant sometimes broken into a family. Coppicing prolongs the life of a tree that responds well to it. Indeed, look at an old hazel that has been left unmanaged and you will often see its limbs leaning like nine pins and snapping at the stump. New growth regenerates from the wound, so management through coppicing simply takes advantage of this nature. The intervention of rotation improves the diversity in the wood, the pool of new light after the fell triggering the ephemerals like foxgloves which by nature live in the halfway place between the wood and the light at the margins.

Here on our banks beneath this recently felled hazel where we have been spreading the primroses about and planting wild daffodils, I expect to see a change these next couple of years. More speedwell, the bulbs basking in spring sunshine to feed their reserves and a proliferation of primrose seedlings that will take this opportunity to extend their reach whilst the going is good. It will not take long – two to three years for the hazel to close over again – and these newly established plants will begin a quieter time in the shadow.

We grade the cuttings, taking the wood for the burner and sectioning the rods for bean poles and the twiggery for pea sticks. The brash is bundled for faggots and a loose weave of unwanted branches is thrown back over the stumps to prevent deer grazing the new shoots in their first important year of ascending upwardly out of harm’s way. It is a process that we are happy to initiate and be part of as the year turns. One of renewal and hope and usefulness. A fine way to start a year that will not be without its challenges.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 9 January 2021

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage