Life is stirring. The hazel streaming with catkin, reflected now in the stillness of the pond. The Cornus mas that I’ve staggered down the ditch are hinting at what is to come. The first flowers that you have to find amongst the branches, open a dark rich yellow. In a fortnight when they are at their peak the trees will glow gently against the backdrop of dormancy still around them. A million tiny flowers contributing to a whole. A shimmer of new life that is happy to run with whichever way February decides to go.

At ground level there is an awakening of celandines and on the warmest banks, primrose and violets. The galanthus are entering their fortnight of peak snowdrop and bolstering me in my annual efforts to extend their reach. The more there are, the further I want them to travel and as soon as their flowers dim, I will spend a couple of Sundays splitting the biggest clumps and replanting them so that the trail continues. To run along the banks of the stream and pool in eddies in the clearings and to line the lane that our fields dip into on our boundaries.

There is joy in the tide slowly turning and, as the garden has evolved, it has become clear that I need to provide for more early risers. To date, spring bulbs and early perennials have been confined to the skirts of the trees and shrubs that punctuate the perennial garden. These areas are cleared in early January whilst the new nibs of growth are still below ground and before they begin to stir, so that they can emerge uninterrupted. The open spaces, which are planted as much for the growing season as for the beauty of the winter skeletons, have a later rhythm and are left standing until the second half of February. Life is made easier in these areas for not having to tread between plants that are on an early growth cycle.

Though it would be nice to have both and a layering of the two, I have to be practical with my time. So, as part of the evolution of this place, it is time to commit to a more generous area where I can enjoy the early risers. Cardamine quinquefolia and wood anemone and drifts of hellebores and first bulbs. A planting that operates on a different timescale, with an early start that dims once the main garden picks up. Somewhere that can be cleared and ready ahead of the areas where I am still enjoying the skeletons.

Making the pond last summer precipitated this opportunity, one creative action leading neatly to opening up another. The hole we made in the ground to provide us with a water body created a considerable pile of subsoil that had to be found a home. This was trundled up the hill where it was regraded into a new landform, extending the level we made around the barns for the kitchen garden. A curving grade to the front was massaged into the existing banks and oversown last September with a perennial wildflower mix to bind the slopes. The carefully saved topsoil from the pond was redistributed over the new plateau and sown with a winter rye and vetch green manure crop to protect the soil over the winter. In March we will rotovate this in and the new ground will be sown with annuals to allow me the time to get used to the space and mull over my next moves.

Above the new plateau, the ground rises up to meet the wild hedgerow I’ve let grow out to provide us with a bat and owl corridor above it and it is on this slope that I will make a new woodland garden. A gentle shade will be cast by a grove of Snowy Mespilus that will connect the eye to the plum orchard beyond and the underplanting will aim to provide us with an early spring garden. A garden with a different rhythm, somewhere to tidy first and enjoy whilst the rest of the garden is yet to think about coming to life. Somewhere for now and somewhere, once spring passes, that can be allowed to simply drop back into shadow like the hazel that are currently holding our attention.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 12 February 2022

This week we have reached the tipping point. The seasonal fulcrum when winter begins the ascent to spring. As the days lengthen we note with excitement the increasing light. ‘4 o’clock! 5 o’clock! 5.30!’.

And with the light and milder days come the flowers. Some are naturally early, like the snowdrops which pass the baton in a relay race from pre-Christmas to their peak in mid-February and the brave early hellebores which sacrifice themselves to the hail and cold driving rain of January. Others, like the Iris reticulata and a few choice narcissus, have been brought on in the cold frames to be brought to the table outside where they prophesy the change of season a few cheating weeks in advance. Pots of hope and anticipation.

But now the first emergents are gathering pace. Winter aconite and witch hazel, pussy willow and violets, cardamine and primrose, wintersweet and cornelian cherry. Diminutive and delicate by and large, but strong and sturdy enough to brave the wintery showers, these torchbearers of the coming wave are always welcome.

Last year the photographer, Eva Nemeth, visited us in every season to photograph the garden for House & Garden magazine. On each visit she also created a speciality of hers, a beautifully composed flat lay of flowers picked from the garden. Earlier this week she posted an image of the one she photographed exactly a year ago on Instagram and we were surprised to see that many of the flowers that were blooming at the beginning of February last year were not yet showing themselves. It prompted me to collect as many of the early showers yesterday to make a comparison.

As you can see there is plenty in the garden to encourage us out, despite the cold. The majority of them are small and delicate and so must be sought out, which is all part of the pleasure, of course. Picking and recording them like this, however, really makes you appreciate the amount of flower even these early risers provide for early foraging bees which, on warm days can already be found thrumming on the snowdrops, hellebores and pulmonaria.

Also this week the findings of a scientific study published by The Royal Society indicate that the flowering times of a wide range of native species has advanced by more than a month (mid-May to mid-April) since the late eighteenth century and has accelerated noticeably in the last thirty years, due to climate warming. Although the early flowers we are seeing today bring cheer and a sense of hope the majority of these plants are still flowering at the times that we are used to. However, the issue of advancing flowering times later in the season is very serious. The two main issues are exposure to frost for species that are not frost hardy, in particular food crops such as fruiting trees, and ‘ecological mismatch’, which occurs when certain species flower out of sync with the insects and vertebrates that are reliant on them for part of their life cycle.

Although the study has not looked at the flowering times of non-native garden plants, one hopes that by planting a wider variety of ornamental garden plants that are closely related to or fill a comparable ecological niche to some of our natives (as shown in the findings of the University of Sheffield’s Biodiversity in Urban Gardens Project (BUGS) and the RHS Plants for Bugs research) will go some way to helping mitigate these issues.

Words & photographs | Huw Morgan

Published 5 February 2022

Last year was the first time that we have grown Jerusalem artichokes here. Not from a lack of desire, but a lack of space. That may sound crazy when our vegetable garden is larger than many peoples’ gardens, but Jerusalem artichokes are voracious plants and you must have enough space to give over to them if they are not to become problematic.

Growing to three metres tall and two metres across they should be placed on the north side of the garden so as not to shade out other crops. On the other hand they can be useful if you have vegetables that need shading or protecting from wind like some brassicas (broccoli, Brussels’ sprouts, kale), salad leaves and oriental greens. We fenced a new productive compound around the polytunneI last winter, so in the spring I ordered five tubers from Otter Farm. Planted 60cm apart and 15cm deep in April by August they had overreached their 4 metre by 1 metre bed and, on our rich soil, have produced a crop of almost 20 kilos in one season.

Not from Jerusalem at all, but a native of North America, Helianthus tuberosus is, as its Latin name indicates, a type of sunflower, a perennial variety which means it should be planted where you intend to keep it, as it will return year after year. Prone to spreading they should be planted where you can get at them easily to curb their invasive tendencies. For the same reason, when harvesting it is important to try to dig up all of the tubers, as a single one left in the ground will cause your colony to proliferate the following year. I have kept five tubers back this year to replant in the same position. Like potatoes Jerusalem artichokes can be a good first crop to plant in previously uncultivated or heavy ground as the growth of the tubers and their subsequent harvesting break up the soil. However, you must remove all trace of them if you plan to grow other crops in their place afterwards.

Ready to harvest from late October onwards Jerusalem artichokes do not store well once lifted and so are best left in the ground and harvested as required. Incredibly hardy they will tolerate winter temperatures down to -30°C. If you have to dig them all up they are best stored in a cool, dark place such as an outhouse, cellar or shed, although they will keep, well-washed and well-dried, in the salad drawer of the fridge for a week or so.

The fleshy, edible tubers are quite unlike any other vegetable in texture or taste. Although starchy like potatoes, they have a sweet, nutty flavour when cooked which is just about comparable to artichoke hearts, but also distinctly its own thing. Unlike potatoes they can be eaten raw, when their texture is reminiscent of water chestnuts. Thinly sliced with a sharp citrus dressing they make an unusual, crisp winter salad.

Their reputation for causing flatulence precedes them and is what often prevents people from growing or eating them. Caused by the inulin they contain, a starch which is difficult to digest, it is not a problem for everyone and it would seem, from personal experience, that the more often you eat them the less of a problem this is.

Their somewhat delicate, earthy flavour is also distinctive and although typically combined with woodsy flavours like bay, sage, thyme and nutmeg, it can hold its own with much stronger flavours and works unexpectedly well with punchy Mediterranean ingredients; tomatoes, red onions, black olives, capers and anchovies.

This recipe is for a rich, velvety and warming soup for a frosty day. Add more liquid if you prefer a thinner soup. Cooked with half the amount of water the resulting purée is a good accompaniment to game birds, chicken and firm white fish. Substitute the artichokes with celeriac or good floury potatoes if the prospect of a windy evening puts you off.

1kg Jerusalem artichokes

40g dried porcini mushrooms

1 small onion

A spring of thyme, to yield about 1 tsp of leaves

50g butter

4 tbsp rapeseed oil

150ml full cream milk

About 1 litre of water

Serves 4

Set the oven to 200°C.

Soak the dried mushrooms in 200ml hot water.

Heat 25g of butter in a large pan over a medium heat. Finely chop the onion and cook for a few minutes until soft and translucent, stirring from time to time.

Remove the porcini from their water. Squeeze the liquid out of them back into the bowl and retain. Coarsely chop two thirds of them and add to the onions with the thyme. Cook together for a few minutes more, stirring occasionally.

Scrub the artichokes extremely well and remove the fibrous hair roots. Trim off any black patches. Reserve one tuber of approximately 100g and cut the remainder into walnut-sized pieces. Put into a roasting pan in a single layer. Drizzle with olive oil and roast in the oven, turning occasionally, for about 30 minutes until softened and caramelised. Add them to the pot with the onions and mushrooms.

Make the mushroom soaking water up to 1 litre with fresh water and add to the pot. Bring to a gentle simmer and cook with the lid on for about 20 minutes until the artichokes are soft.

Blend the mixture until smooth. Add the milk and season with salt and pepper. Return to a very low heat to keep hot.

Melt the remaining butter in a small pan over a medium heat. Coarsely chop the remaining porcini and stew in the butter for a few minutes until soft and glossy. Remove from the pan and reserve.

Add the rapeseed oil to the a pan and raise the heat. Using a very sharp knife or mandolin slice the reserved artichoke very thinly. When the oil is smoking fry the artichoke slices in batches until brown. Drain on kitchen paper where they will crisp up.

Ladle the soup into warm bowls and place a few artichoke crisps and stewed mushrooms on top. Serve piping hot.

Recipe & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 29 January 2022

As I write, the valley is unified by a deep freeze. Deep enough for the ground not to give underfoot and for the first time this winter an icy lens is thrown over the pond to blur its reflection. The farmers use this weather to tractor where they haven’t been able to for the mud. The thwack of post drivers echoes where repairs need to be made to the fences and slurry is spread on the fields that have for a while been inaccessible. It you are lucky, this is exactly the weather when you might get your manure delivery.

I welcome the freeze in the garden, for the last few weeks have been uncannily mild. Warm enough to push an occasional primrose and a smatter of violets. This year we have early hellebores, rising already from their basal rosettes and reminding me to cut away last year’s foliage so that the flowering stems can make a clean ascent. Good practice says to remove the leaves in December to diminish the risk of hellebore leaf spot. So far, whilst I have been nurturing young plants, I prefer to see the flowers pushing before I cut and know that the leaves have done all they can to charge the display.

As the garden matures it is already leaning on me to step in line where in its infancy I retained the upper hand in terms of control. I chose to wait until the end of February before doing the big cut back all in one go to allow as much as possible to run through the season without disturbance. Not so just five years on. I need to start engaging if I am not to make things more and not less labour intensive. It is all my own doing of course, because the more I add to the complexity of the garden, the earlier we have to start to be ready for spring. Where I have planted bulbs amongst the perennials for instance, the bulbs demand that I ready these areas to avoid snubbing their noses.

In terms of letting things be and allowing the garden to find its own balance, I want there to be a push and a pull between what really needs doing and where the natural processes can help me to tend the garden. The fallen leaf litter is already providing the mulch I need to protect the ground under the young trees, so it is in these areas I am concentrating the plants that need early attention. The hellebores and their associated bulbs can now push through the leaf litter. I no longer have need to mulch in these areas and save the annual trim to the hellebores and the shimmery Melica altissima ‘Alba’, the balance here is successfully struck.

We try to get our winter work, which tends to be bigger scale and mostly beyond the garden, all but done by the end of February. Our own fence and hedge work, tree planting and pruning. The ‘light touch’ beyond the garden will see us strim the length of the ditch before the snowdrops come up, but leave it standing for as long as possible where there are no bulbs. We come back on ourselves before the primroses start. Being further down the slope and colder, growth is later there, but the end of February date works. We leave the coppice beyond the ditch untouched, hitting the brambles every three or four years to curb their domain, because the coppice also needs time to establish without competition. Beyond that, and in the areas where we are letting the banks completely rewild, we watch the brambles spread and note how quickly the oaks that have been planted by the jays and squirrels, spring up amongst them. One day the shadow will put pressure on the brambles, which will fall in line and not be the dominating force. Watching what happens and applying your energies only to what is needed is a good reminder for what one should be doing as a gardener back in the cultivated domain.

The tussocky slopes that are too steep to cut on the hay meadows are a beautiful thing. They are very different as a habitat from the machine-managed sward that is kept in check by the hay cut, the grazing and the associated yellow rattle, which will only grow there where it is not outcompeted. The contrast of the tussocky land nearby with its peaks and troughs created by the grazing animals and not a combine provide a place where the rodents live and in turn where the owls and raptors come to feed. In summer you can look into these miniature landscapes and see the other world they offer for yourself. The cool side of a tussock and the warm side where the butterflies bask and the different webs or spiders that take advantage of the peaks and hollows of the undisturbed ground. From our own perspective as custodians and drivers of what happens here, the tussocky ground is a beautiful reminder. Catching the low winter light, its contours draw you to remember that it is good to touch down lightly where you can afford to and only apply your energies at the right time and in the right place.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 22 January 2022

The first of the early season snowdrops are already brightening these darkened days and the season is made that much lighter for their companionship. A winter without them would be a very different thing and I freely admit to being thrown under their spell. A charm that was cast a few years ago with a handful of treasures that were kindly gifted to me by Mary Keen at one of her snowdrop lunches. Snowdrops that she took us to meet in her wintery garden and plants she had taken her time to get to know and were different enough from the usual Galanthus. Plants that gently entice you from the standing position to slow and ponder their particular qualities. A nod that distinguishes them from the crowd, a green tip to the outer petal perhaps, a puckering like seersucker or a completely albino or even gold interior.

I have never been a collector for the sake of collecting and I know from friends who have also found themselves spellbound, that galanthophilia is a slippery slope that can easily lead to a world of obsession and acquisition. That said, and knowing that I wanted to get to know more than a couple of hands full, I struck a pact with myself. To only grow good garden plants. Those which ‘do’ and not those that are fussy and fail on me. I want to be able to see the character of a plant from several paces when it is established and doing what it does best and for each one to offer something distinct. I also want to extend the season forward from February, the main snowdrop season, and to have the company of snowdrops in every week of the winter. Just as I do not want to have hundreds of friends – and bearing in mind that there are 900 or so varieties of galanthus – I just want the ones I can build a relationship with and rely upon. I want the keepers.

It takes time to get to know a plant, so over time I will share with you what I have learned with forms and varieties that are still new to me. The autumn flowering Galanthus reginae-olgae which I have only known for the last three years for instance, which prefer a sunnier, free draining position. It takes three years or so for a single bulb to start to clump and really five before you can see its specific character. How it does in a garden and feels as an individual. A plant such as ‘Fly Fishing’ (kindly gifted, thank you, by our friend Marcia) needs air around it to allow its suspended flowers to dance on elongated pedicels. Timing is also all important, so pairing a variety to coincide with a winter-flowering companion gives a red hamamelis or dark hellebore a bright undercurrent whilst having its moment.

Galanthus are the same as any garden plant. You get a better result for knowing their requirements and how that can be played to best effect in company. As a rule, galanthus like good living and a retentive ground that drains freely and does not lie wet. I planted part of my snowdrop trail in the heavy wet soil at the bottom of the hill where the ground never dries out in summer. The bulbs there failed in the wet areas where the juncus thrived, but the very same soil at the base of trees yielded entirely different results where the trees used the moisture in the summer to give the dormant galanthus a rest. On heavy ground slopes are ideal and hedge banks often provide an ideal position. Lighter soils that are free-draining will benefit from the addition of humus.

Getting to know my collection of ‘specials’ is a learning curve that I am happy to take my time to understand. I buy one bulb of each variety, ideally at the beginning of the growing season so that I can see them complete a life cycle. Paul Barney at Edulis Nursery has a distractingly good collection. I grow them in a stock bed at the base of a hawthorn hedge where in summer they can retreat into safe dormancy. Once they have started bulking, in the third year or so, the clumps are lifted as soon as they have flowered and moved to where I want them to be in the garden. Somewhere close to a path so that I can get to them easily and planted in good company so that they are not overwhelmed too early by precocious pulmonarias or cow parsley.

Of the three plants I am sharing with you this early into my chapter of snowdrop distraction, Galanthus plicatus ‘Three Ships’ (main image) is the first to flower after the relay of autumn snowdrops. ‘Three Ships’ was found under an ancient cork oak by John Morley in Suffolk and is reliably in flower at Christmas. Rare for G. plicatus to flower this early, it sits low to the ground over broad widely-spreading foliage, the rounded petals puckered and distinctly textured to capture dew or low, raking light.

Galanthus elwesii ‘Maidwell L’ was kindly gifted by Simon Bagnall, head gardener at Worcester College, Oxford, once again with the generosity of one galanthus lover to another (thank you). This is an early flowering form of G. elwesii, the broad-leaved species that has spawned a number of early to rise varieties. This is a good one, welcoming the first of January this year and showing vigour and willingness to do well on our heavy ground. I have loved this plant for the graceful unfurling of grey-green foliage, leaves which are broad and unroll like a scroll. A selection from Maidwell Hall, Northamptonshire made by Oliver Wyatt, the flowers stand tall at about 22cm and hold good poise.

Nearby, under the medlar I have a group of Galanthus elwesii ‘Mrs Macnamara’ (thank you Mary). Named after Dylan Thomas’s mother-in-law who grew it in her garden, it is reliably early and well known for good behaviour. Again, in flower by the first of the month or sometimes a little earlier, this is a nicely proportioned plant that you can recognise from a distance. Narrow, glaucous foliage is not as much part of the mood as it is with ‘Maidwell L’, but it all sits together very pleasingly, the large, slender flowers held perfectly, each in their own space like a drawing of a perfect snowdrop, but with perhaps a little more of everything.

Snowdrops should be split every five or six years to retain vigour in the clumps. I like to plant a couple of bulbs together or three for company as some sit and sulk and are slow to increase if planted alone. Do not ask me why and this is not the case for everybody. Divisions are best made after flowering or as the leaves fade into dormancy and before your attention is drawn elsewhere in spring and the spell they have cast over the winter is broken. As you lift and divide and extend the reach of the plant in question you are left with nothing but good feeling, as you pat the soil and say a little prayer that you will see them again after the commotion of a growing season is spent and done and quietened to allow them their glory.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 15 January 2022

And so, as another year draws to an end we would like to thank you all for your support, encouragement and engagement over the past 12 months.

We are taking a break for a few weeks and will return in early January.

We wish you all a very happy and healthy Christmas and a peaceful New Year.

Arrangement & photograph: Huw Morgan

Published 18 December 2021

I start to look differently when the last of the foliage is finally pulled from the trees. The nakedness of winter limbs reveals what went undercover in the growing season and I slowly walk our land and take note. The growth on the hedges, the advance of the brambles that sat in their shadow and that this year might need curtailing. The mental map of winter work as the season stretches out ahead of us is now clear and visible.

As the garden matures and there is more to manage, I am bringing the pruning forward in the season so that it can be savoured and never rushed. Woody plants such as mulberry and grape vine that have a tendency to bleed are pruned first. The Strawberry Grape, which we have planted alongside the open barn has sent its limbs into the gutters and without attention will begin to get the upper hand. Pruning it back to an orderly framework in turn triggers one of the first winter jobs. The taking of hardwood cuttings.

Hardwood cuttings could not be easier, if you take them as soon as the foliage drops and the sap is still in the wood and not yet drawn back to root. Unlike summer cuttings, which need cossetting to keep them hydrated whilst they are also trying to form roots, a hardwood cutting does not have to put energy into foliage. It will instead spend the next few weeks initiating roots that will already have formed as it comes back into leaf again in the spring.

Hardwood cuttings suit many, but not all, deciduous shrubs. Willow and dogwoods, roses and honeysuckle, figs and vines to name a handful. A cutting should ideally be pencil thick and much the same length, with a flat cut below a joint or bud at the bottom and a sloping cut above a bud at the top to shed water. The angle of the cut also identifies which is top and bottom, something that is not always easy as you gather up the nest of vine cuttings that has been cast on the floor after you have pulled it from the gutters.

As space is limited in my cold frames, I take only what I need and have plans for. Plants which might need to be moved in the garden and make an easier move for being a youngster or those which have sentimental value or are hard to get hold of. The figs are a good example and I make a number of plants every year for clients and friends. A few from the cut-leaved ‘Ice Crystal’ (main image) and the same for the ‘White Marseille’. Perhaps the best of all the figs that can be grown outdoors in southern England, my cutting was given to me by Alastair Cook, the former head gardener at Lambeth Palace. This remarkable tree was planted at the palace in 1556 by the last Roman Catholic Archbishop to reside there, Cardinal Reginald Pole. Today it makes an environment of its own, twisted and touching down to the ground to root where it has done so. With this in mind, my plant here at Hillside is grown in a large pot, but one day it will be liberated so that we can walk amongst its branches to harvest the honeyed, lime green fruits.

Hardwood cuttings of figs are best taken with tip growth rather than a series of pencils cut to length from a stem, as with the vines. They are left for a little over a year in the pot and then re-potted in spring to grow away in readiness for planting out in the autumn two years after being taken. A short wait if you have a relay of plants as I do, but important to have in the wings as the cuttings represent a kind of security. They have the value embedded in their histories and I have a mental list of homes that will enjoy being part of their diaspora.

An easy rooter such as a willow can save on all the efforts of potting up and frame life as it can be struck very easily right where you intend it to live out its life. This is how I have been stepping the Salix purpurea ‘Nancy Saunders’ down into the wild wetness of the ditch. The cuttings take minutes, though I take the time to choose strong healthy wood as this always makes the best propagation material. The young limbs or ‘rods’ are simply pushed into the ground with a foot or so in the soil to root and give enough purchase to hold them upright. With a little height and sap in the stem to help them take root over winter they will have the advantage. They need to, for they will be left to their own devices, with not much more than a fond thought to fight it out with the meadowsweet come summer, whilst I get on with the winter works that lie ahead.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 11 December 2021

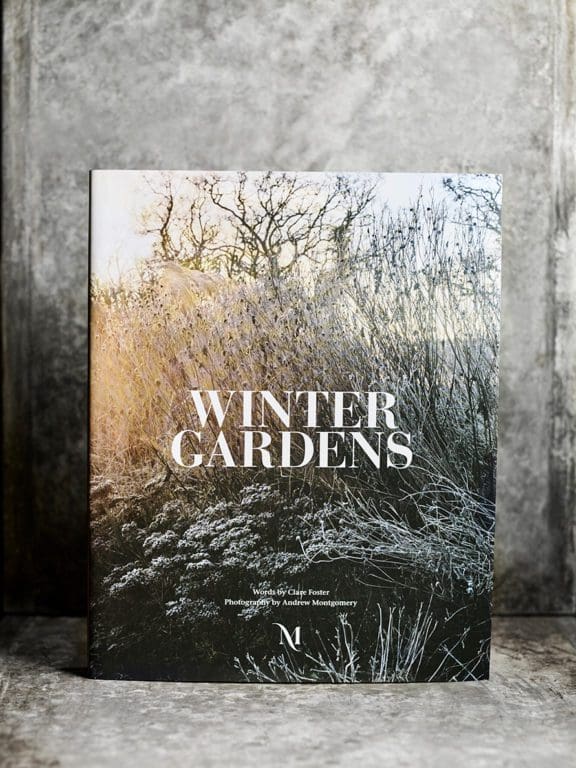

Last December, just days after Christmas, we received an email from Clare Foster, gardens editor at House & Garden magazine. She wanted to know if we would be happy for the garden at Hillside to be photographed by Andrew Montgomery for a new self-published book they were working on together. The focus of the book was to be gardens in winter and they had set themselves the task of getting it written, photographed, designed and published within 10 months.

On a perfect misty morning in early January with the garden covered in hoar frost Andrew arrived just before sunrise. He immediately got to work with total focus and proceeded to work into the early afternoon when the mist finally dissipated and his frost-bitten fingers could take the cold no more. The book has now been published and features gardens by Arabella Lennox-Boyd, Arne Maynard, Jinny Blom, Piet Oudolf and Tom Stuart-Smith amongst many others. Here Clare and Andrew tell us about how the book came about and what they feel is particular and special about the garden in winter.

Tell me how the idea for the book came about? What inspired you to create a book about winter gardens?

Clare: Andrew and I had worked on a couple of winter garden features for House & Garden and one in particular we had been trying to capture for a couple of years, waiting for the right moment. In lockdown, Andrew started photographing seed heads and ruminating on the idea of doing a book. I seized on the idea and came up with a list of other gardens which I thought captured the beauty of winter in very different ways. We were lucky – the weather was reasonably cold last winter – and we managed to get most of them photographed in atmospheric frost, mist or snow.

Andrew: Winter Gardens came about in December 2020, during the second lock-down. Having seen all my photography commissions put on hold until well into 2021, I had this free time all of a sudden where I could do what I wanted, so decided to photograph and put together my own book. Having spent the previous 10 months, including the first lockdown, putting together a book for Petersham Nurseries which was a self-published project, I knew I could do it. Winter Gardens was the perfect subject. Covid secure, I could shoot whenever I wanted with no human contact. More importantly it appealed to my own personal desire to see gardens in a new way. Stripped of colour, a monochromatic palette where light and shadow became paramount. The gardens became a muse for my love of black and white photography. Mist, snow, frost all enhanced the medium, which I felt had never really been properly explored in garden photography.

Gardens are often referred to as out of season in the winter. Can you tell us why you felt differently?

Clare: When you slow yourself down and really start looking at the garden and landscape in winter you notice the most amazing nuances. It is the sort of beauty that might not jump out at you, but once you adjust your eye it becomes a marvellous thing. There is no such thing as ‘out of season’ – winter is very much a season to be celebrated in the garden, with a chance to slow down and appreciate everything in suspended animation. And the other thing is, if you don’t have the quietness and downtime of winter you don’t appreciate the cycle of growth as it appears again in spring. It’s sort of magical, really.

Andrew: Out of season seems to suggest they have nothing to offer. I had a conversation with one of the gardeners at Great Dixter discussing frost. She remarked that the first frost was always the most magical, as if it signified the curtain call of Autumn, those brown warm shapes and tones suddenly enveloped by a crystal blue cloak, a portent of what is to follow. This sparked the need to witness and photograph this inaugural wintry pistol crack. So over previous winters I have always felt the need to try and capture this moment.

The winter season offers something different to capture, something much more subtle. The garden is dormant, quiet, its bones and earth bereft of colour, where weather dominates the mood and feel of the space, enhancing what is left for us to see. It also gives us a chance to really reflect on what went before, but also gives us hope as to what is to come. Winter is the season of reflection.

How did you go about selecting the gardens you chose for the book? What was the story you were wanting to tell?

Clare: We wanted there to be some very contrasting gardens in the book to show that there are different ways to bring beauty and interest into the winter garden. The book is divided into three sections that take you conceptually through early, mid and late winter, to show that winter is not a static season at all, but has its own momentum towards spring. Three essays group the gardens into different types: Beauty in Decay features gardens with grasses and seedheads; Silhouette and Structure looks at gardens with a stronger topiary framework; and A Shy Flowering contains gardens with winter or earliest spring flowers. The last garden in the book shows everything cut neatly down and mulched ready for spring. One senses the hope of the new year.

Is there anything you learned about the process of gardening while researching, writing and producing the book that was either new to you or came as a surprise?

Clare: I learned to really, really look at the process of senescence in my own garden. In certain plants, the seed heads and stems collapse quickly; others are incredibly strong and last for months and months before you have to fell them in March. I noticed what rain or frost did to my honesty seed heads and this close observation brought so much pleasure. I also learned quite a lot about snowdrops from the head gardener at Lord Heseltine’s garden at Thenford. They have a collection of about 900 varieties and she knows almost everything there is to know about propagating them.

Can you tell us about some of the challenges you face photographing gardens in winter?

Andrew: The challenges – well the obvious one is the cold. It’s debilitating both to people and battery life! Fingers become useless after prolonged exposure to the cold, disconnected from the brain you begin to fumble the camera controls, struggling to operate something which usually you do without looking. The cold becomes tiring, tripods and ladders too cold to touch with bare hands. Gloves, thermals and merino wool layers help massively. Cameras also don’t like the cold, and you have to acclimatise them slowly to the conditions, otherwise condensation builds up on lenses and viewfinders.

There’s also always a chance in the winter that you’re not going to be able to get to the garden you’re supposed to be photographing due to ice or heavy snowfall. Either that or, having headed off at dawn into the frost and snow, you find that by the time you get there it’s disappeared! One of the gardens was a particular challenge and it took four attempts to get the pictures that appear in the book. The garden is just off the M4 not far from London, not an area known for snow. The fourth attempt was only successful as I was supposed to be going down to Dorset to do a shoot that morning, but couldn’t get there as the A303 was snowbound. So I took a gamble on the fact that it was probably snowing at this other garden, which was much closer. This was at 5 a.m. so I just decided to turn up and hope the owners didn’t mind! Of course, I was incredibly lucky and got some beautiful shots of the garden in the snow.

The book is beautifully thought through, laid out and paced. Who designed it for you?

Andrew: I designed and laid out the whole book and the individual gardens and chapters. Editing is a process which I love. Pacing the run of photographs for each garden, juxtaposing images, mixing colour and black and white. It’s just like planning and planting a garden – extremely creative. You are mindful of what comes before and next, not wanting to repeat yourself visually. Always trying to make each image earn its right to be on that page and in the book.

Once I had everything laid out and the gardens organised into chapters, I would then work with a great guy called Anthony Hodgson who was able to put everything into Indesign for me and put the book together for printing. He also handled all the typesetting and font choices in the book.

Andrew, at the book launch you said that the image you took at Hillside which you titled The View to the Tump, ‘is probably the most spiritual picture I have ever taken.’ I’d really like you to expand on that and tell me why.

Andrew: The View to the Tump is an image that had been one of my favourites throughout the book’s editing process. It was the best shot from my day’s shoot at Hillside, but it was when I saw it enlarged to over 3ft by 2ft on the table in the printers that its power really struck me. I became quite emotional seeing it for that first time at that scale. I had only ever viewed it on my computer screen at home where it was no bigger than A4 size. The scale of the print, which was to be hung with two other prints of Hillside for an exhibition to celebrate the book launch of Winter Gardens, had made it an immersive experience.

Once hung on the wall I began to see that the image was a glimpse of another world, familiar to ours yet somehow removed. The gate in the image took on the metaphor of the entry into that other world, as if this was a glimpse of heaven beyond.

Now for me to say these things about any image, let alone one of my own, is unheard of, but this one is different and stems from my emotional reaction to it. This is a rare, profound feeling that has happened only once or twice in all my thirty years of taking photographs, but it’s the spiritual connection that The View to the Tump has that makes it unlike anything I have taken before.

Can you tell me what it is you see in winter seedheads and skeletons, which your son, Clare, described as a ‘a load of depressing old sticks’?

Clare: Every seed head has a different structure, a unique design that is revealed slowly as the plant decays. Some of them are really sturdy and strong, others are delicate and ethereal, but they are all marvels of nature. I find that photographing them sometimes makes me focus more keenly on them, especially if I’m doing close up or macro shots that reveal the tiniest detail. I think this is something that you almost have to learn to do, and I will try and teach my 17 year old son to open his eyes to it. But I don’t think he’s ready yet….

You first contacted us about this book just after Christmas last year, since when you have written, photographed, edited, designed, proofed and published this completely on your own. Can you describe what it has it been like self-publishing a book from scratch in just under a year and what have been the particular challenges?

Clare: It has been a complete whirlwind. We are both incredibly hard workers. We get things done, but it has been a fantastic experience because we have had complete creative control. Obviously Andrew takes the photographs and it was his eye that brought the book together, but he was very open to my suggestions and ideas and together I think we have made something that represents both our creative souls. We have made something with integrity that I think we are both incredibly proud of.

Andrew: The timescale to produce a book of this scale would normally be 1-2 years, so to do it in 10 months would, to a normal publisher, be impossible. We had planned out our production schedule, image editing, design, writing, copy editing and proofing to meet our deadline of July 29th. Files would then be sent to the printers and our book scheduled to arrive mid-October for our November 4th publication deadline.

The challenge was doing this alongside our normal careers at the same time, which put a huge amount of pressure on both of us. We just knuckled down and worked all hours on it. We really wanted the book to be published this winter, not a year later, and it could not come out at any other time of year either.

The most stressful part was waiting for the ship carrying our books to arrive in Portsmouth. The pandemic had played havoc with shipping routes and schedules and watching the boat make its eight week voyage over a live-view feed on the internet with publication day looming was nerve-wracking. In the end I took delivery with just two days to spare!

Now that you have one book under your belts do you have any plans for another? If so, are you able to tell us anything about it?

Clare: Yes – another book is definitely in the pipeline. Another garden book. Watch this space!

Andrew: Well, it’s very exciting that we know what book two will be! It’s going to be another garden based book, but we can’t say more than that. We are aiming to release it sometime in 2023, but to enable us to do that book we are working as hard as we can now to make Winter Gardens the success we feel hopefully it deserves to be!

Winter Gardens costs £45 and is available to buy directly from Montgomery Press.

An exhibition of Andrew’s photographs from the book is being held in the old tithe barn at Thyme, Southrop, near Lechlade until April 4 2022.

Interview: Huw Morgan | All photographs © Andrew Montgomery

Published 4 December 2021

Cultivated in England since the early part of the 16th century, the black mulberry is a tree that has a timeless quality. A ruggedness that speaks of previous custodians, of care and cultivation and lives lived around it. A mature tree, squat and always rounded, shows the decades in its fissured bark and the mosses and lichens that find a home there on twisting limbs. Limbs that often reach to the ground under their own weight and lean on elbows to root where they have rested. If you step inside the cradle of branches you find a leafy world within, the lush foliage hiding bloody fruits, like sharp, juicy loganberries, that stain your hands and mark your appetite in August.

As Morus nigra have been widely cultivated for so long, it is not known from where exactly they originated. Mesopotamia and Persia are listed when you try to understand their requirements and, though vague, this does explain their desire for a warm position and their preference for southern England. As temperatures warm their range will surely extend slowly north so they may well become more widespread as vineyards move up the country. They are often grown in association in Persia since the conditions vines favour are typical of their preferred habitat. Warm slopes and free drainage. Somewhere that basks in sunshine.

Morus nigra was mistakenly introduced into this country in the belief that it was the fodder for silkworms. The white mulberry (Morus alba) – the real food crop of the silkworm and a bigger tree – has inferior fruit and less charisma in a garden. However, you will often be sold it as a substitute since they are more easily grown in the field. Black mulberries are rarely sold as large plants and are most often containerised and supplied as feathered maidens of not more than 1.5m. That said, they are not as slow as you might imagine and begin to show character remarkably early in life.

Our mulberry was one of the first trees I planted in our first winter here in 2011. Though I only had the garden in my mind’s eye at that point, I placed a young maiden in the rectangle the farmer before us had carved out of the field to grow his brassicas. Now that I know the land better and the winds that race down the valley, I see why he had put his only growing patch just here. It has the hedge behind it and the shelter of the house not so far away. Despite the fact that there were no trees here initially, I instinctively knew that a mulberry would be my gateway tree to the garden that one day would follow. A tree that would eventually hug the hill and make this place into a garden as it matured and brought with it that certain gravity.

Planting trees early in a project is a rewarding milestone with time mapped in new branches. My youngster, with all its promise, sat amongst the rotations of our temporary vegetable and perennial trial garden for the following five years. Every year gathering a little more strength and presence and slowly making us work further around it to ensure its well-being. By the time I finally made the garden in the summer of 2016, it was already the deciding factor for where the paths would sit to either side. One grass path to the rear and the other – the primary route into the garden – on the sunny side. Ten years in, and with the garden now grown around it, the tree has already formed its own microclimate, a pool of shade beneath, where pulmonarias and snowdrops trigger spring and a place on the grassy walk behind where the grass is cool and shady on a summer’s day. Together with the medlar which is planted nearby, it already gives this young garden a feeling of age and establishment.

Though in time I know my tree will become idiosyncratic, with limbs and character that I could never plan for, I like to set a young tree in the right direction with formative pruning to establish a good framework. In the case of the mulberry, the structuring of the tree is also to keep it open with free air movement, because in the last couple of years we have slowly seen mulberry leaf spot wither the lush foliage in high summer.

Leaf spot, a fungal infection caused by either Cercospora moricola or Phloeospora maculans, is quite common on mulberries. It is noted that the fungus is most prevalent in wet conditions, and recent outbreaks in Turkish orchards have followed mild, wet winters, so we avoid watering near the tree on the rare occasions I put out the oscillator. This year we also applied a neem oil spray every fortnight as soon as the tree broke bud, which had a noticeably positive impact. Of course, come a busy August, there wasn’t time to be consistent, and so spraying stopped, but the tree has done better for it, only showing signs of infection again in September. We have cleared the fallen foliage to remove the spores that fall with the foliage and hope as time goes on that it will be only be a problem in wet summers.

Mulberries bleed to their detriment if you prune in the second half of the winter, so I do this in late autumn as the leaves drop and the sap is being drawn back. It is an easy and meditative process and I remove a small amount only, to thin the limbs and not trigger sappy regrowth. The time spent with the tree allows me the opportunity to imagine the branches reaching out and over the paths one day. An easy reach for a luscious berry as we enter and exit the garden and take pleasure in the knowledge that with time this tree will only get better.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 27 November 2021

A benign autumn has drawn this beautiful season out and the wood below us, our backdrop and litmus for seasonal change, has taken its time. The poplars are the first to return to bare bones, their sage-green plumage blackening before it falls the distance. Standing grey-limbed and newly naked, their retreat into dormancy reveals the relationships in the wood. A pool of yellow where the hornbeam are happy under the poplar’s influence and the luminous understorey of hazel. Casting my mind back to spring, the Corylus were last visible when they stirred with creamy catkin and it has been the summer since we were aware of them on all but the fringes. As late to lose their leaves as they were early to catkin, the last fortnight has seen them flare a second time, but it won’t be long before the winter sun once again falls to earth to graze the contours and the silvery line of the stream.

Although the wood is separated from our perch on the hillside by the slopes that run below us, when you are immersed in the garden, the wood is drawn deliberately close. Walking the paths in the tall autumn garden, the two become one, working at different scales but on the same principles. The layering of taller plants revealing the understories and movements of plants that now come into their second season. Panicum that ignite as they colour and the butteryness of the Euphorbia that step through the planting and bring it together as the hazel does in the wood.

Brightest of them all in this last run of colour are the Amsonia hubrichtii, the Narrow Leaved Bluestar from Arkansas. Their first moment is in early summer when they break a late dormancy and race to flower when the garden is flooded with energy. At this point they are more flower than foliage, clusters of blue-grey stars appearing around knee height and at the reach of their stems. Though undeniably pretty, they are modest plants and are the support act to the Iris sibirica through which they are planted. Once their flowers dim you all but forget about them as they quietly fill out to form a mound of needle-fine foliage.

I have kept the plants deliberately close to the path so that they have enough sunshine to remind them of home and their place in open grassland. They are staggered on both sides of the path so that the path and the repetition allows your eye to carry as it does in the woods with the glowing hazel. Those that catch the best of the light have done better than those that get overshadowed, so it is worth remembering to keep them in the company of plants that come later in the season and do not crowd them out when they are building up their strength for seed production and another year. When they are happy, Amsonia are long lived plants, happy to sit in one position like a peony or a baptisia, going without division or additional cosseting.

In tandem with the last colour in the woods, the Amsonia have become more luminous in this final fling. Lighting up as if from within, they are visible again under the Molinia, giving the last of the asters the company they need to not feel alone. If their autumn blaze had a function other than to bring us pleasure, you could say that they were quietly planning for this moment. Their flash of glory before winter finally takes hold.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 20 November 2021

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage