We leave the garden now to stand into the winter and to enjoy the natural process of it falling away. The frost has already been amongst it, blackening the dahlias and pumping up the colour in the last of the autumn foliage. Walk the paths early in the morning and the birds are in there too, feasting on the seeds that have readied themselves and are now dropping fast.

I have combed the garden several times since the summer to keep in step with the ripening process, being sure not to miss anything that I might want to propagate for the future. The silvery awns on the

Stipa barbata, which detach themselves in the course of a week, can easily be lost on a blustery day. This steppe-land grass is notoriously difficult to germinate and a yearly sowing of a couple of dozen seed might see just two or three come through. My original seed was given to me in the 1990’s by Karl Förster’s daughter from his residence in Potsdam, so the insurance of an up-and-coming generation keeps me comfortable in the knowledge that I am keeping that provenance continuing.

The seed harvest is something I have always practiced and, as a means of propogation, it is immensely rewarding. Many of the plants I am most attached to come from seed I have travelled home with, easily gathered and transported in my pocket or a home-made envelope. Seedlings nurtured and waited for are always more precious than ready-made plants bought from a nursery but I have learned the art of economy and sow only what I know I will need or think I might require if a plant proves to be unreliably perennial for me. The

Agastache nepetoides, for instance, came to me via Piet Oudolf where they grow taller than me in his sandy garden at Hummelo. However, they are unreliable on our heavy soil and need to be re-sown every year. Fortunately, they flower in the same year and I can plug the gaps where they have failed in winter wet with young seedlings sown in March in the frame and planted out at the end of May.

Agastache nepetoides

Agastache nepetoides

Over the years, as much by trial and error as by reading about the requirements and idiosyncrasies particular to each plant, I have learned the rules. The Agastache for instance will not germinate if the seed is covered, so they will fail to appear spontaneously in the garden if you mulch or sow and then cover the seed, as I usually do, with a topping of horticultural grit. The seed needs light and should just be gently pressed into the surface so that they can be triggered. The Agastache seed keeps well and is easily sown in spring, but the viability of seed is different from plant to plant.

Primula vulgaris gathered and sown directly a couple of years ago saw seedlings germinate readily within a month that same summer. Last year I was busy and waited until September to sow, but the seed had already begun to go into dormancy, an inbuilt mechanism to save it in a dry summer. The overwintering process of stratification, which will unlock dormancy with the freeze, thaw, freeze, saw the seedlings germinate the following spring. The plants consequently took a whole six months longer to get them to the point that I could plant them out into the hedgerows, but I learned and will save myself that delay come the future.

Molopospermum peleponnesiacum

Molopospermum peleponnesiacum

As a rule the umbellifers tend to have a short life and the seed does not keep, so I sow my giant fennel, Astrantia and Bupleurum as soon as the seed is ripe and overwinter it in the cold frame. This year, for the first time. I have sown

Molopospermum peleponnesiacum and, though it is a reliable perennial, I am keen to see if I can rear some youngsters. This ferny-leaved umbel is early to rise and I love it for the gloss and laciness of its foliage and the horizontality of its lime green flowers. I have it amongst my Molly-the-Witch peonies and their early presence together is a good one. I’m also simply curious to learn more about the life cycle of this European umbel, as I find I understand a plant better if I know how long it will take to become a parent and what it takes to get it to the point of seeding and germinating successfully.

Paeonia delavayi

Paeonia delavayi

My

Paeonia delavayi are the grandchildren of an original plant I grew from seed I collected when I was nineteen and working at the

Edinburgh Botanic Gardens. The plants in the garden have started to lose whole limbs this year, which I am putting down to the heat, but it could just as easily be honey fungus. Having a few youngsters in the background is good insurance, but I am sowing the seed fresh because peony seed needs a chill and sometimes two winters before growth appears above ground. The first year is all about the formation of roots so, as a general rule, I never throw a pot of seed out for two years just in case.

Asclepias tuberosa

Asclepias tuberosa

This is the first year I have grown the tangerine milkweed,

Asclepias tuberosa, and would like to get to know it better. It is said to suffer from winter wet, which is a given living where we do in the West Country, so my seed sowing is insurance again and a means of bulking up the little group I have amongst my black-leaved clover. The seed is exquisite, the claw-like pods rupturing on a dry day to spill their silky contents on the breeze. Reading up reveals that the seed also needs winter stratification, so I have sown it now in a lean, gritty compost to ensure it is free-draining and that the seed doesn’t sit wet. A gritty seed compost will ensure the seedlings search for nutrients and grow a good strong root system once they have germinated in the spring. I prefer to top dress with grit rather than soil to inhibit moss and algae build-up, which can cap the pots if they are sitting around for a while in the frame.

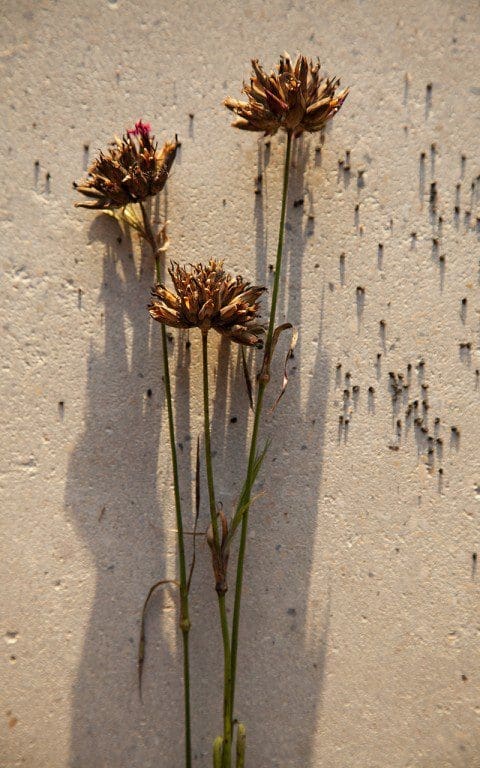

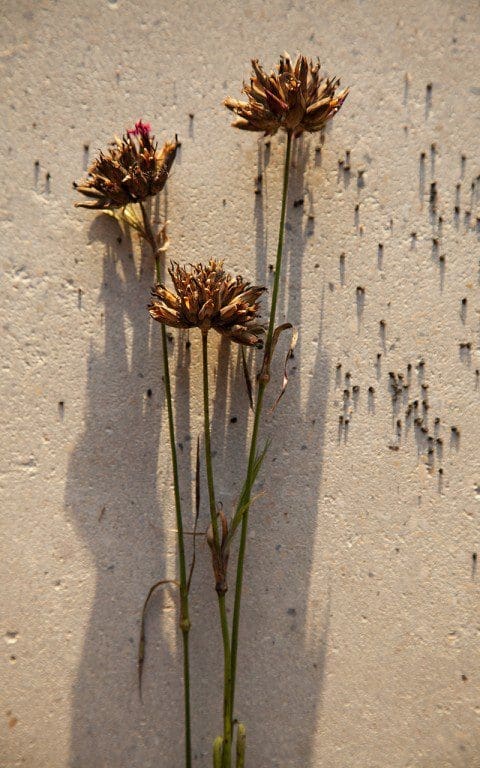

Dianthus carthusianorum (in second image with Achillea ‘Moonshine’)

Dianthus carthusianorum (in second image with Achillea ‘Moonshine’)

Although I like to sow most of my hardy plants in the autumn to avoid storing them when they could be beginning their journey, I like a few in hand to simply scatter about and help in the process of naturalising where I want my plants to mingle. The

Dianthus carthusianorum are this year’s project, and so I am scattering seed at the tops of my dry banks where I hope they will take in the most open parts of my wildflower slopes by the house. A cast of thousands is easily made up in a handful, but it takes only one to begin a colony.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 17 November 2018

Agastache nepetoides

Over the years, as much by trial and error as by reading about the requirements and idiosyncrasies particular to each plant, I have learned the rules. The Agastache for instance will not germinate if the seed is covered, so they will fail to appear spontaneously in the garden if you mulch or sow and then cover the seed, as I usually do, with a topping of horticultural grit. The seed needs light and should just be gently pressed into the surface so that they can be triggered. The Agastache seed keeps well and is easily sown in spring, but the viability of seed is different from plant to plant. Primula vulgaris gathered and sown directly a couple of years ago saw seedlings germinate readily within a month that same summer. Last year I was busy and waited until September to sow, but the seed had already begun to go into dormancy, an inbuilt mechanism to save it in a dry summer. The overwintering process of stratification, which will unlock dormancy with the freeze, thaw, freeze, saw the seedlings germinate the following spring. The plants consequently took a whole six months longer to get them to the point that I could plant them out into the hedgerows, but I learned and will save myself that delay come the future.

Agastache nepetoides

Over the years, as much by trial and error as by reading about the requirements and idiosyncrasies particular to each plant, I have learned the rules. The Agastache for instance will not germinate if the seed is covered, so they will fail to appear spontaneously in the garden if you mulch or sow and then cover the seed, as I usually do, with a topping of horticultural grit. The seed needs light and should just be gently pressed into the surface so that they can be triggered. The Agastache seed keeps well and is easily sown in spring, but the viability of seed is different from plant to plant. Primula vulgaris gathered and sown directly a couple of years ago saw seedlings germinate readily within a month that same summer. Last year I was busy and waited until September to sow, but the seed had already begun to go into dormancy, an inbuilt mechanism to save it in a dry summer. The overwintering process of stratification, which will unlock dormancy with the freeze, thaw, freeze, saw the seedlings germinate the following spring. The plants consequently took a whole six months longer to get them to the point that I could plant them out into the hedgerows, but I learned and will save myself that delay come the future.

Molopospermum peleponnesiacum

As a rule the umbellifers tend to have a short life and the seed does not keep, so I sow my giant fennel, Astrantia and Bupleurum as soon as the seed is ripe and overwinter it in the cold frame. This year, for the first time. I have sown Molopospermum peleponnesiacum and, though it is a reliable perennial, I am keen to see if I can rear some youngsters. This ferny-leaved umbel is early to rise and I love it for the gloss and laciness of its foliage and the horizontality of its lime green flowers. I have it amongst my Molly-the-Witch peonies and their early presence together is a good one. I’m also simply curious to learn more about the life cycle of this European umbel, as I find I understand a plant better if I know how long it will take to become a parent and what it takes to get it to the point of seeding and germinating successfully.

Molopospermum peleponnesiacum

As a rule the umbellifers tend to have a short life and the seed does not keep, so I sow my giant fennel, Astrantia and Bupleurum as soon as the seed is ripe and overwinter it in the cold frame. This year, for the first time. I have sown Molopospermum peleponnesiacum and, though it is a reliable perennial, I am keen to see if I can rear some youngsters. This ferny-leaved umbel is early to rise and I love it for the gloss and laciness of its foliage and the horizontality of its lime green flowers. I have it amongst my Molly-the-Witch peonies and their early presence together is a good one. I’m also simply curious to learn more about the life cycle of this European umbel, as I find I understand a plant better if I know how long it will take to become a parent and what it takes to get it to the point of seeding and germinating successfully.

Paeonia delavayi

My Paeonia delavayi are the grandchildren of an original plant I grew from seed I collected when I was nineteen and working at the Edinburgh Botanic Gardens. The plants in the garden have started to lose whole limbs this year, which I am putting down to the heat, but it could just as easily be honey fungus. Having a few youngsters in the background is good insurance, but I am sowing the seed fresh because peony seed needs a chill and sometimes two winters before growth appears above ground. The first year is all about the formation of roots so, as a general rule, I never throw a pot of seed out for two years just in case.

Paeonia delavayi

My Paeonia delavayi are the grandchildren of an original plant I grew from seed I collected when I was nineteen and working at the Edinburgh Botanic Gardens. The plants in the garden have started to lose whole limbs this year, which I am putting down to the heat, but it could just as easily be honey fungus. Having a few youngsters in the background is good insurance, but I am sowing the seed fresh because peony seed needs a chill and sometimes two winters before growth appears above ground. The first year is all about the formation of roots so, as a general rule, I never throw a pot of seed out for two years just in case.

Asclepias tuberosa

This is the first year I have grown the tangerine milkweed, Asclepias tuberosa, and would like to get to know it better. It is said to suffer from winter wet, which is a given living where we do in the West Country, so my seed sowing is insurance again and a means of bulking up the little group I have amongst my black-leaved clover. The seed is exquisite, the claw-like pods rupturing on a dry day to spill their silky contents on the breeze. Reading up reveals that the seed also needs winter stratification, so I have sown it now in a lean, gritty compost to ensure it is free-draining and that the seed doesn’t sit wet. A gritty seed compost will ensure the seedlings search for nutrients and grow a good strong root system once they have germinated in the spring. I prefer to top dress with grit rather than soil to inhibit moss and algae build-up, which can cap the pots if they are sitting around for a while in the frame.

Asclepias tuberosa

This is the first year I have grown the tangerine milkweed, Asclepias tuberosa, and would like to get to know it better. It is said to suffer from winter wet, which is a given living where we do in the West Country, so my seed sowing is insurance again and a means of bulking up the little group I have amongst my black-leaved clover. The seed is exquisite, the claw-like pods rupturing on a dry day to spill their silky contents on the breeze. Reading up reveals that the seed also needs winter stratification, so I have sown it now in a lean, gritty compost to ensure it is free-draining and that the seed doesn’t sit wet. A gritty seed compost will ensure the seedlings search for nutrients and grow a good strong root system once they have germinated in the spring. I prefer to top dress with grit rather than soil to inhibit moss and algae build-up, which can cap the pots if they are sitting around for a while in the frame.

Dianthus carthusianorum (in second image with Achillea ‘Moonshine’)

Although I like to sow most of my hardy plants in the autumn to avoid storing them when they could be beginning their journey, I like a few in hand to simply scatter about and help in the process of naturalising where I want my plants to mingle. The Dianthus carthusianorum are this year’s project, and so I am scattering seed at the tops of my dry banks where I hope they will take in the most open parts of my wildflower slopes by the house. A cast of thousands is easily made up in a handful, but it takes only one to begin a colony.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 17 November 2018

Dianthus carthusianorum (in second image with Achillea ‘Moonshine’)

Although I like to sow most of my hardy plants in the autumn to avoid storing them when they could be beginning their journey, I like a few in hand to simply scatter about and help in the process of naturalising where I want my plants to mingle. The Dianthus carthusianorum are this year’s project, and so I am scattering seed at the tops of my dry banks where I hope they will take in the most open parts of my wildflower slopes by the house. A cast of thousands is easily made up in a handful, but it takes only one to begin a colony.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 17 November 2018

Previous

Previous

Next

Next