Three years ago, Troy Scott-Smith invited me to become a Garden Advisor for the garden at Sissinghurst. It was a role I was happy to explore, for I have known the garden for years as a visitor, but there is nothing like getting to know a place better from behind the scenes and through the people that work there.

Anyone who owns or gardens a garden knows all too well that feeling of only seeing what needs doing. Sometimes it is hard to focus on the achievements, the long view or to simply take stock and see what is happening in the here and now. My annual meetings with Troy take place in a different season every year, with notebooks and an open brief to walk and talk and ponder. This year I made my visit in late March, a good time to evaluate a garden while the structure is still visible.

A second eye from an outsider is often exactly what is needed and we have cultivated an openness in the discussion, where opinions may count here but not there, and where the shared mission is to get to the essence of things. For me, this is a complete luxury, as I am free of the responsibility I have in my role in the design studio and can look without having to provide more than an honest opinion.

Head Gardener, Troy Scott-Smith

Head Gardener, Troy Scott-Smith

By way of introduction Troy had sent me his manifesto before my first visit. When he applied for the role as Head Gardener he talked openly of the need for change and, to the credit of the National Trust, they employed him to implement this vision. He absolutely did not see this as change for change’s sake, but a means of recapturing the potent sense of place that Vita Sackville-West celebrated in her writing about the garden that she and Harold Nicolson had made at Sissinghurst Castle; a garden inextricably linked to the buildings it surrounded and, in turn, the Kentish farmland and countryside that swept up to its walls.

Troy saw the need for the place to be unlocked again from the rigour that had become the way that people came to know the garden after the death of Vita and Harold in the 1960’s. A challenge perhaps for the most famous garden in the country but, for one with such good bones, a new era of excitement.

The Top Courtyard

The Top Courtyard

Beyond the wall of the Top Courtyard is Delos

Beyond the wall of the Top Courtyard is Delos

The White Garden

The White Garden

The Orchard

The Orchard

The Cottage Garden with topiary yews (left) and the Rondel (right) with the Rose Garden to the right. The Lime Walk can be seen running to the left of the exit at the top of the Rondel.

The Cottage Garden with topiary yews (left) and the Rondel (right) with the Rose Garden to the right. The Lime Walk can be seen running to the left of the exit at the top of the Rondel.

I expect that there are very few good gardens that are the product of one vision. Gardens are places where skills come together and, indeed, where they work in combination to make the whole altogether stronger. Vita and Harold’s relationship was a perfect example. He with his architectural mind providing the structure and she, the romantic, the counterpoint of informality. Her writings talk of a place that was, first and foremost, lived in by its owners and where ideas and experiments did not demand year-round perfection. However, the garden then did not have the pressures it has now with up to 200,000 visitors a year. Mulleins breaking into the paths could be negotiated and roses reaching beyond their allocated space were free to reign.

Vita wrote well about her gardening experiences and possessed a powerful vision, but she was not a professional gardener. She was learning as she evolved the garden and, like all of us, her mistakes and failures were probably as numerous as her successes. Clambering roses overwhelmed the apple trees to bring them down where their vigour wasn’t matched, and some areas of the garden were simply allowed to recede into the background when out of season. There were bold and visionary moves, such as the tapestry of polyanthus in the Nuttery that would ultimately fail to disease and need rethinking.

When the National Trust took over in 1967, five year’s after Vita’s death, an inevitable tightening up eventually saw the garden reach extraordinary horticultural heights in the hands of Pam Schwerdt and Sibylle Kreutzberger who worked with Vita from 1959 until she died, but went on to make the garden their own during their 30 year tenure as joint head gardeners. Pam and Sibylle’s prowess with plants was a large part of what brought visitors to Sissinghurst in their droves in the 1970’s and ’80’s, securing its place as one of the most influential gardens in the world. The way the garden became was ultimately driven by the need to provide for increasing numbers of visitors and, in so doing, the intimate sense of place was slowly and gradually altered.

Troy and Dan in the Lime Walk

Troy and Dan in the Lime Walk

The Lime Walk

The Lime Walk

In the Rose Garden

In the Rose Garden

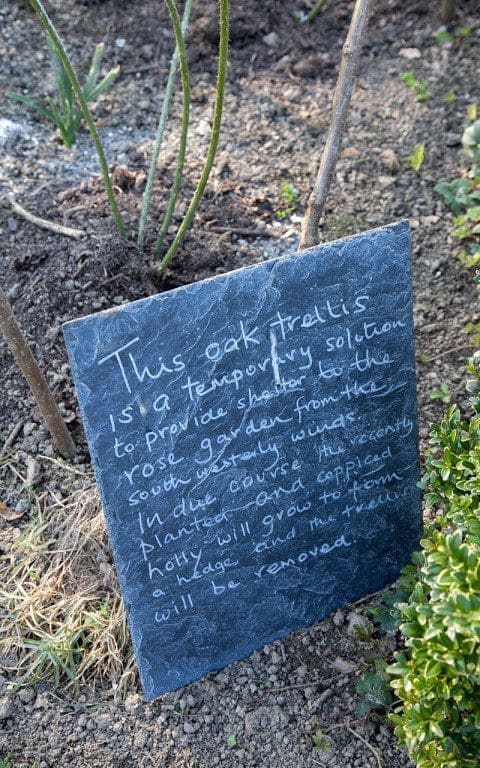

New oak trellis in the Rose Garden

New oak trellis in the Rose Garden

Yew hedges are gradually being reconditioned with hard pruning

Yew hedges are gradually being reconditioned with hard pruning

I have known Sissinghurst since I was a child. My father and I would visit every summer and walk its enclosures with notebooks in hand. I remember very distinctly the feeling of awe and then panic fused with disappointment that we would simply never be able to garden to this level of perfection. So we would drive on determinedly to Great Dixter to take the antidote of a garden living and breathing its owner and not attempting to garden with belt and braces. Even when the blueprint is strong gardens can easily assume a different character, for a garden is really the gardener.

And now Troy is slowly and gently making changes. He has turned the lawns at the approach into meadow and reinstated an old cart pond. There is a new hoggin entrance and there is talk of returning some of the brick and stone paths in the gardens to grass. If they wear, people will be redirected until the grass recovers, to preserve the calm and intimacy of the softer surface.

Roses that were tightly trained against the walls were given a couple of years off to reach away from their constraints. New apple trees have replaced old and the cigar-shaped yews in the Top Courtyard are being allowed to grow out into a looser shape, as they were in Vita’s day. The Little North Garden (formerly the Phlox Garden) was for years made inaccessible from the White Garden after the steps were removed in 1969. It has been reconnected with new steps which will provide another way out when the White Garden is at its peak and crowded. And Troy is planning on re-instating the phlox that once grew there in Vita’s time and after which she named it.

The yews in the Top Courtyard are being allowed to grow out into a looser shape as they were in Vita’s day

The yews in the Top Courtyard are being allowed to grow out into a looser shape as they were in Vita’s day

Discussing Troy’s planting plans for the Little North Garden. The new stone steps lead up to the White Garden.

Discussing Troy’s planting plans for the Little North Garden. The new stone steps lead up to the White Garden.

The White Garden. The Little North Garden is reached through the arch in the boundary wall.

Dan and Troy discuss recent new additions to the White Garden

Dan and Troy discuss recent new additions to the White Garden

A newly planted olive in the White Garden

A newly planted olive in the White Garden

For years the Kentish Weald was the driving force and counterpoint to the formality of the garden and its enclosures, so we have talked of taking pressure off the garden and of making it less introverted, opening it up again to the land around it. The Nuttery has been enlarged, with new coppice hazels, a softer secondary path and a permeable fence boundary to the fields beyond. By removing the later addition of the hedge along the Nuttery, the field and the lake it flanks instantly provide a visual decompression. There is now talk of allowing people into the meadow and down to the lake so that, when the garden is busy, it provides an overspill area. After many years without them, Troy is also planning to reinstate Vita’s massed plantings of polyanthus in some areas.

The Nuttery

The Nuttery

Original stone path in the Nuttery

Original stone path in the Nuttery

New soft path in the Nuttery, with additional coppice hazel and visually permeable split chestnut fencing

New soft path in the Nuttery, with additional coppice hazel and visually permeable split chestnut fencing

Last year, Joshua Sparkes, one of the enthusiastic young gardeners working with Troy, won a scholarship to visit Delos, the inspiration for one of the garden areas that has lost its way. Vita and Harold had been inspired by the Greek island and had strewn the area beyond the Top Courtyard with a small number of artefacts and stone walls to conjure a Greek hillside. Facing north and with exposure to the winds from across the fields, the site was not the ideal place to try such an experiment.

Later incarnations saw the garden protected on the windward side with a hedge of Pemberton roses and a canopy of magnolias took over to provide more shade, which subsequently saw the garden become home to primarily woodland plants. However, Troy has a little grove of cork oaks waiting in the nursery and Joshua’s research has identified a number of Greek natives to bring out the spirit of the place again. It may not be exactly as Vita and Harold had intended, but they wouldn’t have stood still either. As gardeners I have the feeling they would have embraced change and all the excitement and energy that comes with it.

Delos

Delos

Spring planting in Delos

Spring planting in Delos

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Previous

Previous

Next

Next