A perfectly ripe fig, picked fresh from the tree. Heat in the fruit and the energy of a long, hot summer caught in sweet, juicy flesh. I can think back to specific trees that marked a moment in time. On our daily walk to the beach in Andalucia, in a baking courtyard in Seville, a dusty, walled garden in California or standing alone in the boulder-strewn landscape of Greece. Surviving against the odds, but producing such succulent fruit despite the stark contrast of their surroundings.

The equivalent fruit in our moist, forgiving climate might be the pear. At its moment of perfection, they are the most delectable of cool climate fruits. You can taste that they love the land like figs love the sun. However, our quest as gardeners is to always push the boundaries and have what we know might be out of reach. So we experiment, in order to capture a memory, or outmanoeuvre the limitations of our site.

Though our land here is bathed in sun, the conditions couldn’t be more different from the native habitats of Ficus carica. A fig growing in the Middle East will have to make do with scant winter rainfall and many months of summer drought. To find moisture it sends its roots deep down a crack in a rock or reaches for the cool, damp ground beneath a boulder. In the wild, weeks of uninterrupted sunshine might slowly defoliate it, but the energy continues to be directed into a high-summer ripening and the formation of embryonic fruits for the following year. Look on spring wood that has harnessed the winter rains and the next year’s figs will already be formed.

Here in Britain our steady supply of water and mild winters are a licence to grow and, as a consequence, fig trees can be unruly creatures. Since they feel less under threat to reproduce, they put their energy into leaf and can easily throw a limb of a couple of metres in a season. Clients that have a small garden in north London have two trees that were almost certainly one before it leant down and layered itself from the mother plant. When they arrived and took over the long-neglected property, it was a world of fig, both inside and out. A green light shone through fig leaves pressed against the third storey windows and limbs reached into and over the neighbours’ gardens. The clients loved the fig mood and we are doing our very best to find a way to inhabit the garden beneath them and allow them to retain their domain.

The Victorians, who liked to challenge what was possible, made elaborate provision to grow figs in high-backed lean-to glasshouses. The roots were contained pits made from slabs so the vigour in the limbs would be curtailed to encourage the energy to go into fruit production. Despite the root restriction, a glass-grown fig needs careful pruning if it is not to outgrow its space and it is rare to see one today since all of the above equate to quite a luxury of space and time.

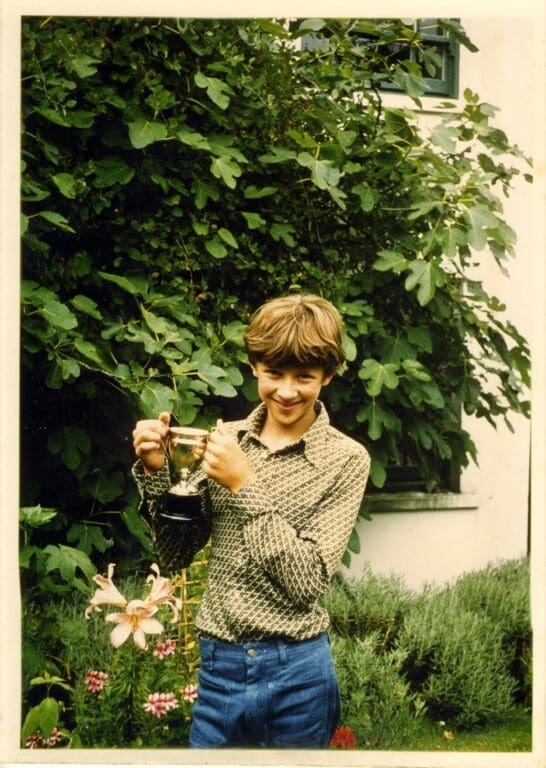

Geraldine, my childhood gardening mentor, had a tree of ‘Brown Turkey’ growing on her hot, south-facing wall. Her Nerines and Algerian Iris grew beneath and she would regularly bring baskets of the fruit across the lane for us to share. I remember thinking that they were a grown-ups’ fruit, but here we are all these years later with a plant of our own against the barn. Though ‘Brown Turkey’ (main image) do not have the quality of the honeyed, black figs that stay in the mind from trees I’ve encountered in the Mediterranean, they are certainly worth growing. Although late to ripen, this year the tree is weighted heavily, presumably the result of last year’s scorching summer. We have dried a batch in the desiccator for winter compotes, are eating the plumpest and making spoon sweets out of those that are still green.

I have two more figs here at Hillside, each in positions where they can bask with their backs against a wall to make the most of the reflected heat. Ficus afghanistanica is grown for its foliage rather than the fruits, which are small and hard and, as its name suggests, would only ever be possible to grow for eating in a hotter climate. The foliage is deeply cut and varies considerably across the species. Cassian Schmidt, the former director of Hermannshoff Gardens in Germany, showed me a batch successfully grown from fruits he’d found in a market in the Middle East. Some were slashed as deeply as Herb Robert and they were all different. Our cultivar here is called ‘Ice Crystal’. Fig foliage has a calming presence and a gently decadent air and though I don’t yet know quite how large ours is going to grow, it is already a fine presence in the six years it has been at the back of the herb garden.

The fig I have most hope for is a cutting that was the ‘White Marseilles’ given to me by Alistair Cook, the former Head Gardener at Lambeth Palace. The tree there was planted in 1556 by Cardinal Reginald Pole, the last Roman Catholic Archbishop of Canterbury. It is an extraordinary tree taking up the space of a tennis court, reaching away from the palace walls and leaning on its elbows in a great sprawl of limbs. Possibly the best of all the figs you can grow out in the open in the south of the UK, ‘White Marseilles’ is pale and sweet and as good as a fig gets in this country. And every autumn I take a handful of hardwood cuttings to pass on to friends. We savoured the four fruits that ours produced this summer, which momentarily transported us to the hot terraces of Greece.

With the mother plant in mind, I have had mine in a large pot for the last six years, but it has sulked and the time has finally come to give it a home in the ground against the end of the barn. I will not be making a pit to contain its roots because, given the vigour of its growth, the ‘Brown Turkey’ has quite obviously escaped the one I made for it. Although I know I will be giving up the end of the barn to the ‘White Marseilles’, I have a hunch that the figs will suit our new and potentially drier climate and that, in time, it may well not be the pears that are the most delectable fruit on our south-facing hillside.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 11 November 2023

Previous

Previous

Next

Next